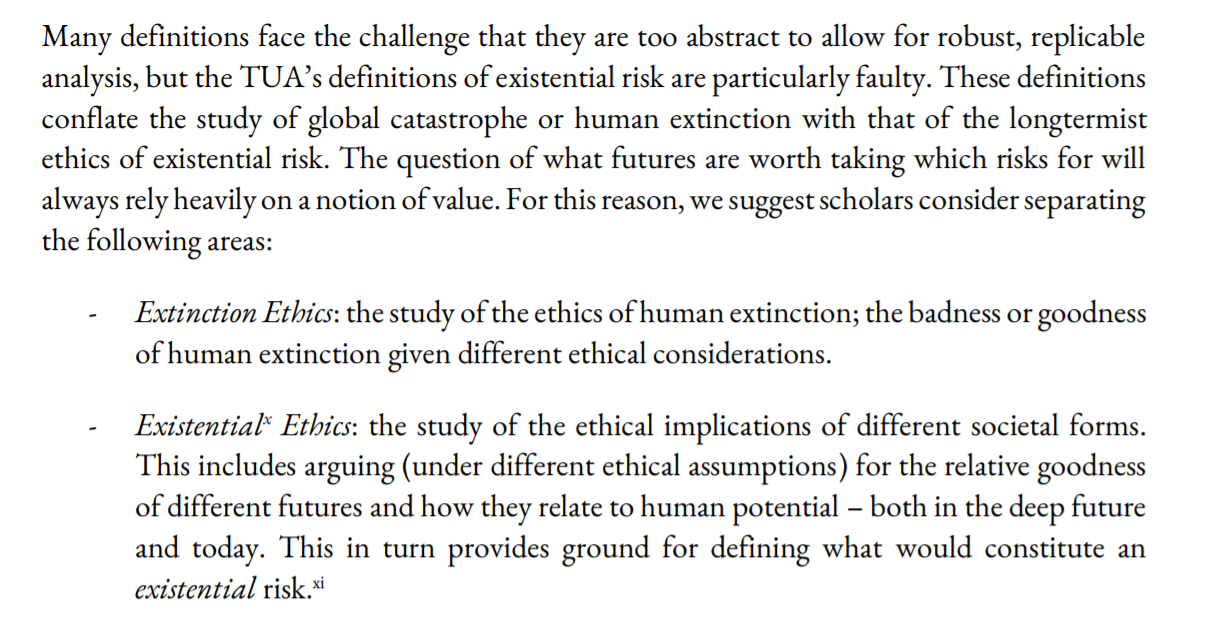

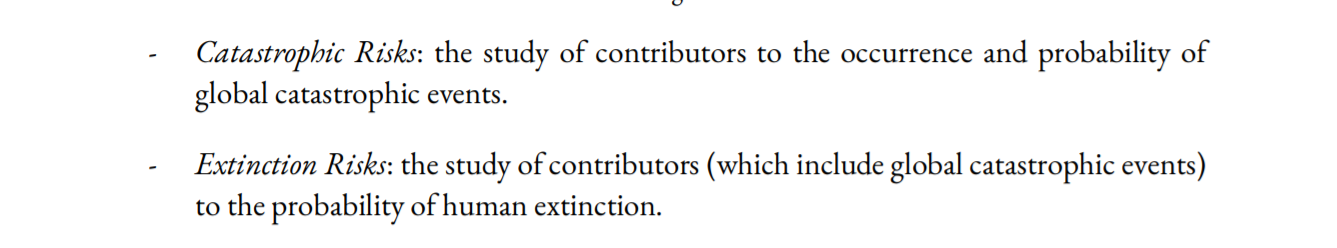

Luke Kemp and I just published a paper which criticises existential risk for lacking a rigorous and safe methodology:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3995225

It could be a promising sign for epistemic health that the critiques of leading voices come from early career researchers within the community. Unfortunately, the creation of this paper has not signalled epistemic health. It has been the most emotionally draining paper we have ever written.

We lost sleep, time, friends, collaborators, and mentors because we disagreed on: whether this work should be published, whether potential EA funders would decide against funding us and the institutions we're affiliated with, and whether the authors whose work we critique would be upset.

We believe that critique is vital to academic progress. Academics should never have to worry about future career prospects just because they might disagree with funders. We take the prominent authors whose work we discuss here to be adults interested in truth and positive impact. Those who believe that this paper is meant as an attack against those scholars have fundamentally misunderstood what this paper is about and what is at stake. The responsibility of finding the right approach to existential risk is overwhelming. This is not a game. Fucking it up could end really badly.

What you see here is version 28. We have had approximately 20 + reviewers, around half of which we sought out as scholars who would be sceptical of our arguments. We believe it is time to accept that many people will disagree with several points we make, regardless of how these are phrased or nuanced. We hope you will voice your disagreement based on the arguments, not the perceived tone of this paper.

We always saw this paper as a reference point and platform to encourage greater diversity, debate, and innovation. However, the burden of proof placed on our claims was unbelievably high in comparison to papers which were considered less “political” or simply closer to orthodox views. Making the case for democracy was heavily contested, despite reams of supporting empirical and theoretical evidence. In contrast, the idea of differential technological development, or the NTI framework, have been wholesale adopted despite almost no underpinning peer-review research. I wonder how much of the ideas we critique here would have seen the light of day, if the same suspicious scrutiny was applied to more orthodox views and their authors.

We wrote this critique to help progress the field. We do not hate longtermism, utilitarianism or transhumanism,. In fact, we personally agree with some facets of each. But our personal views should barely matter. We ask of you what we have assumed to be true for all the authors that we cite in this paper: that the author is not equivalent to the arguments they present, that arguments will change, and that it doesn’t matter who said it, but instead that it was said.

The EA community prides itself on being able to invite and process criticism. However, warm welcome of criticism was certainly not our experience in writing this paper.

Many EAs we showed this paper to exemplified the ideal. They assessed the paper’s merits on the basis of its arguments rather than group membership, engaged in dialogue, disagreed respectfully, and improved our arguments with care and attention. We thank them for their support and meeting the challenge of reasoning in the midst of emotional discomfort. By others we were accused of lacking academic rigour and harbouring bad intentions.

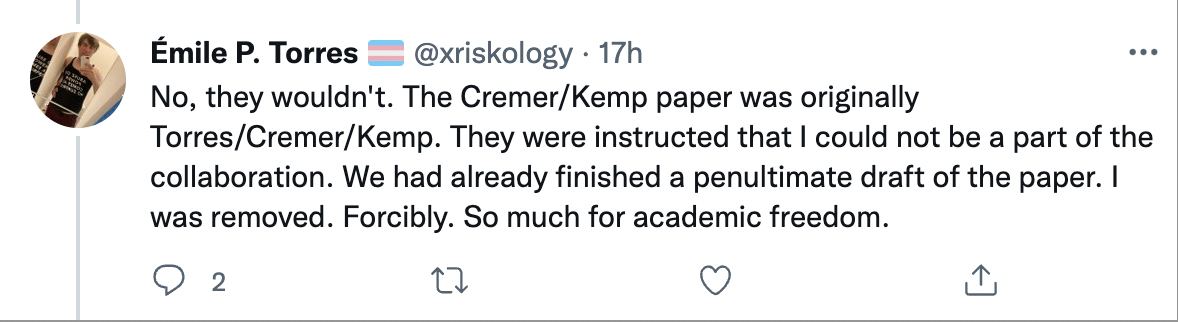

We were told by some that our critique is invalid because the community is already very cognitively diverse and in fact welcomes criticism. They also told us that there is no TUA, and if the approach does exist then it certainly isn’t dominant. It was these same people that then tried to prevent this paper from being published. They did so largely out of fear that publishing might offend key funders who are aligned with the TUA.

These individuals—often senior scholars within the field—told us in private that they were concerned that any critique of central figures in EA would result in an inability to secure funding from EA sources, such as OpenPhilanthropy. We don't know if these concerns are warranted. Nonetheless, any field that operates under such a chilling effect is neither free nor fair. Having a handful of wealthy donors and their advisors dictate the evolution of an entire field is bad epistemics at best and corruption at worst.

The greatest predictor of how negatively a reviewer would react to the paper was their personal identification with EA. Writing a critical piece should not incur negative consequences on one’s career options, personal life, and social connections in a community that is supposedly great at inviting and accepting criticism.

Many EAs have privately thanked us for "standing in the firing line" because they found the paper valuable to read but would not dare to write it. Some tell us they have independently thought of and agreed with our arguments but would like us not to repeat their name in connection with them. This is not a good sign for any community, never mind one with such a focus on epistemics. If you believe EA is epistemically healthy, you must ask yourself why your fellow members are unwilling to express criticism publicly. We too considered publishing this anonymously. Ultimately, we decided to support a vision of a curious community in which authors should not have to fear their name being associated with a piece that disagrees with current orthodoxy. It is a risk worth taking for all of us.

The state of EA is what it is due to structural reasons and norms (see this article). Design choices have made it so, and they can be reversed and amended. EA fails not because the individuals in it are not well intentioned, good intentions just only get you so far.

EA needs to diversify funding sources by breaking up big funding bodies and by reducing each orgs’ reliance on EA funding and tech billionaire funding, it needs to produce academically credible work, set up whistle-blower protection, actively fund critical work, allow for bottom-up control over how funding is distributed, diversify academic fields represented in EA, make the leaders' forum and funding decisions transparent, stop glorifying individual thought-leaders, stop classifying everything as info hazards…amongst other structural changes. I now believe EA needs to make such structural adjustments in order to stay on the right side of history.

I also feel like the comment doesn't seem to engage much with the perspective it criticizes (in terms of trying to see things from that point of view). (I didn't downvote the OP myself.)

When you criticize a group/movement for giving money to those who seem aligned with their mission, it seems relevant to acknowledge that it wouldn't make sense to not focus on this sort of alignment at all. There's an inevitable, tricky tradeoff between movement/aim dilution and too much insularity. It would be fair if you wanted to claim that EA longtermism is too far on one end of that spectrum, but it seems unfair to play up the bad connotations of taking actions that contribute to insularity, implying that there's something sinister about having selection criteria at all, without acknowledging that taking at least some such actions is part of the only sensible strategy.

I feel similar about the remark about "techbros." If you're able to work with rich people, wouldn't it be wasteful not to do it? It would be fair if you wanted to claim that the rich people in EA use their influence in ways that... what is even the claim here? That their idiosyncrasies end up having an outsized effect? That's probably going to happen in every situation where a rich person is passionate (and hands-on involved) about a cause – that doesn't mean that the movement around that cause therefore becomes morally problematic. Alternatively, if your claim is that rich people in EA engage in practices that are bad, that could be a a fair thing to point out, but I'd want to learn about the specifics of the claim and why you think it's the case.

I'm also not a fan of most EA reading lists but I'd say that EA longtermism addresses topics that up until recently haven't gotten a lot of coverage, so the direct critiques are usually by people who know very little about longtermism. And "indirect critiques" don't exist as a crisp category. If you wanted to write a reading list section to balance out the epistemic insularity effects in EA, you'd have to do a lot of pretty difficult work of unearthing what those biases are and then seeking out the exact alternative points of view that usefully counterbalance it. It's not as easy as adding a bunch of texts by other political movements – that would be too random. Texts written by proponents of other intellectual movements contain important insights, but they're usually not directly applicable to EA. Someone has to do the difficult work first of figuring out where exactly EA longtermism benefits from insights from other fields. This isn't an impossible task, but it's not easy, as any field's intellectual maturation takes time (it's an iterative process). Reading lists don't start out as perfectly balanced. To summarize, it seems relevant to mention (again) that there are inherent challenges to writing balanced reading lists for young fields. The downvoted comment skips over that and dishes out a blanket criticism that one could probably level against any reading list of a young field.