This is a crosspost for Why the New Administration Should Consider Farm Animal Welfare by Robert Yaman, which was published on 17 December 2024. I am not affiliated with Innovate Animal Ag. The crosspost starts in the next paragraph.

Since we’re entering giving season, I wanted to remind folks that much of the research that goes into this Substack is done by a nonprofit think tank, Innovate Animal Ag. If you feel like you’ve learned something valuable from us, I would be eternally grateful if you supported our work. There’s always a cost-benefit analysis that goes into working on new posts versus other projects, and your support makes it easier justify continuing to publish regularly.

Alternatively, it would also really help if you shared this Substack with someone you felt might get value from it, or promoted it on social media. Thank you so much for your support!

Share The Optimist's BarnA new administration is about to take office, some members of which have expressed interest in tackling issues related to animal welfare. As it stands, animal welfare as a political cause skews left in the US, with the exception of a few heterodox groups like the White Coat Waste project. I thought this would be a good opportunity to re-examine the political economy of animal welfare, and think through how the government ought to be involved in ensuring that farm animals are treated in line with society’s values. I argue that government subsidies for animal welfare, if thoughtfully applied, are a powerful and neglected way to improve animal welfare, and could be more effective than the more punitive policies that have historically been pursued.

Animal welfare as a public good

There is a well-documented and somewhat mysterious phenomenon in cultural attitudes towards farm animal welfare known as the “vote-buy” gap. This means that often people express strong support for farm animal welfare in surveys, and even vote for farm animal welfare laws, but this seeming support doesn’t always translate to purchasing behavior at the store. For example, in 2018 California voters passed Proposition 12 with over 62% of the popular vote, banning the sale of eggs from hens in conventional caged systems. Proposition 12 then became law, and 100% of the eggs sold in California became cage-free over the course of the next six years.

Before Proposition 12, significantly less than 62% of the eggs purchased in California were cage free (at the time, cage-free only accounted for 18% of national production). On its face, this is weird. A large number of people seemingly voted to have everyone else switch to cage-free eggs even though they primarily ate eggs from conventional caged systems. Do as I say, not as I do.

Many hypotheses have been put forth to try to explain this. Maybe voters already thought that they were eating cage-free eggs when they weren’t. Maybe, deep down, people want a more humane husbandry system, but when they arrive at the supermarket and see the rising price of eggs, their moral fortitude fails them. Maybe people had never really thought about the fact that conventional egg production involves cages until they read the ballot. Or, maybe people are just irrational.

I think the best way to explain the vote-buy gap is to understand the implicit mental model under which people are operating. One naive way to understand people is the “individualized model.” Under this mental model, the eggs I eat come from an individual hen, who exists somewhere either in or out of a cage. The question of whether to buy cage-free eggs then comes down to whether I think it’s right for that hen who laid those eggs to be kept in a cage. However, under a different model, which we might call the “collective model,” the eggs I eat come from “the egg industry” rather than an individual hen. My personal decision to buy cage-free eggs has a minimal effect on “the egg industry,” but if I vote for a law dictating what kind of husbandry system we as a society want, then I can be part of changing “the egg industry.”

The vote-buy gap seems irrational under the individualized model, because I would essentially be voting to force myself to adopt a behavior that I could easily voluntarily adopt. Under the collective model, my behavior is more understandable, because I’m voting to change something that I myself am powerless to impact through my purchasing decisions. The collective model better explains why people act differently at the ballot box versus the grocery store, giving us a clearer picture of how the public actually thinks about farm animal welfare.

The collective model is also clearly demonstrated in the climate space. The exhaust from my car has a miniscule effect on climate change, but the laws passed by the politicians I vote for have a massive effect. Climate change and animal welfare are different in the sense that the harms of poor welfare can be isolated to an individual animal, whereas the harms of carbon emissions are extremely diffuse. And indeed, the concentrated harm of animal welfare is one reason why a highly-engaged observer might assume people operate under the individualized model in this instance. However, for the average person, food is completely abstract by the time they arrive at the grocery store, and the countless complexities that go into making any food product are far from front of mind.

The analogy between animal welfare and climate points to the notion of animal welfare as a public good, just as clean air is a public good. We exist in a society with a “food system,” and people have preferences about the ways the food system works beyond how they interact with it as consumers. People clearly care about farm animal welfare, and they want our food system to treat animals well, but they don’t really have a way to influence this unless they themselves are farmers. Changing the world into something that people prefer benefits them, so when conditions on farms improve, in a way, everyone benefits.

Under this framing, the benefit of improving animal welfare is that it satisfies the values and preferences of humans. This might be unintuitive given that, from a moral point of view, the reason animal welfare matters isn’t because it improves human health or makes consumers safer. It’s because animals matter intrinsically. However, animals aren’t agents in our economic system, so there is no way to directly price in their preferences. Therefore, the value of better welfare is best realized by satisfying human preferences for a food system that treats animals humanely.

Who pays?

As our primary vehicle of collective action, the government is clearly in the business of supplying public goods. There are well-understood ways of doing this through public policy that we can borrow from other fields.

However, one of the complexities of farm animal welfare as a public good is that it’s provided by private entities. For some public goods, like policing, firefighting or public park maintenance, the government is fully in charge of administering the service. But for animal welfare, farmers are in charge of raising animals to feed us, not the government. In this way, the analogy between animal welfare and climate goes even deeper. Our society’s impact on climate change is also mostly mediated through private companies. Given that ensuring good animal welfare costs money, the key question is therefore who should pay for this good.

There are two broad ways to deal with the costs of public goods administered by private companies. One is to force the private companies to pay for the public good on their own dime. In effect, this means the cost is largely passed on to the customers of those companies. The other is to offer to compensate private companies insofar as they provide the public good, in which case everyone in society pitches in through taxes.

Historically, public policy initiatives around animal welfare reflect the first option by banning certain practices or punishing companies for wrongdoing. For example, California’s Proposition 12 mandates that anyone selling eggs in the state must use cage-free systems. If a farmer only has access to conventional caged systems, that’s too bad. They can upgrade on their own dime or stop selling eggs in California.

On first glance, passing costs on to consumers through producers might seem more efficient, because people end up paying for welfare to the extent that they purchase animal products. One might make an analogy to public bridge tolls, where it makes sense for citizens to pay for the bridge in proportion to how much they use it.

However, if we fully adopt the collective model, the opposite is actually true. Having a more humane system is something that benefits everyone, so it would make more sense for everyone to pitch in through taxes. In fact, it’s a little weird that, if a citizen cares so much about welfare that they abstain from animal products, they end up not contributing at all to the cost of having better animal welfare. These people would be active contributors if welfare was achieved through subsidies instead of bans.

Another benefit of subsidies over bans is that, with subsidies, taxpayer funds can go to high-leverage activities like funding R&D or transition costs to better systems. With bans, the increased cost that consumers pay goes directly to paying for better welfare, which has no leverage. Funding R&D or transition costs are particularly impactful for technology because they can help new technologies come down the cost curve, or reach better supply and demand equilibria.

Further, in rich countries, animal product consumption tends to be negatively correlated with income. Therefore, a ban whose cost is primarily passed onto consumers functions as a regressive tax. In contrast, a subsidy funded by taxes can easily have a more progressive structure.

I would argue that, in the animal welfare space, the reason for historical emphasis on bans isn’t because of a clear-eyed analysis of the pros and cons of different policy options. Rather, I think it stems from a punitive mindset toward bad actors that I associate with progressive-style activism. There’s also an embedded assumption tied a vegan mindset that if the price of animal products goes up, then people will eat less of it, which is a good thing.

The politics of animal welfare

Indeed, placing animal welfare in explicit tension with food prices is the most powerful argument opponents of initiatives like Proposition 12 have had. It’s important to keep food affordable, and politicians clearly realize this—just think about the role inflation played in the last election.

On the other hand, the main argument against positive incentives for welfare is that they require money that could be spent on other things. But this is a common problem for many public policies. And from a political economy perspective, we’ve seen that people are much more open to being taxed slightly more than paying more for something as fundamental as food.

This is why positive incentives have been much so much more powerful in the climate space. Negative incentives like a carbon tax have never gotten off the ground, despite decades of discussion in the public sphere. In fact, some argue that unpopular negative incentives pushed by Democrats such as Clinton’s energy tax actually caused the political polarization around climate policy that held it back for decades, despite good intentions. In contrast, government incentives have been a driving force behind some of the environmental movements' big wins, such as the transition to LED lightbulbs.

The most significant climate legislation to be passed in recent history is the Inflation Reduction Act, which is mainly focused on positive incentives for green technology. Something at the scale of the IRA isn’t in the cards for animal welfare anytime soon, since most people don’t view animal welfare as equally important to other issues like climate.

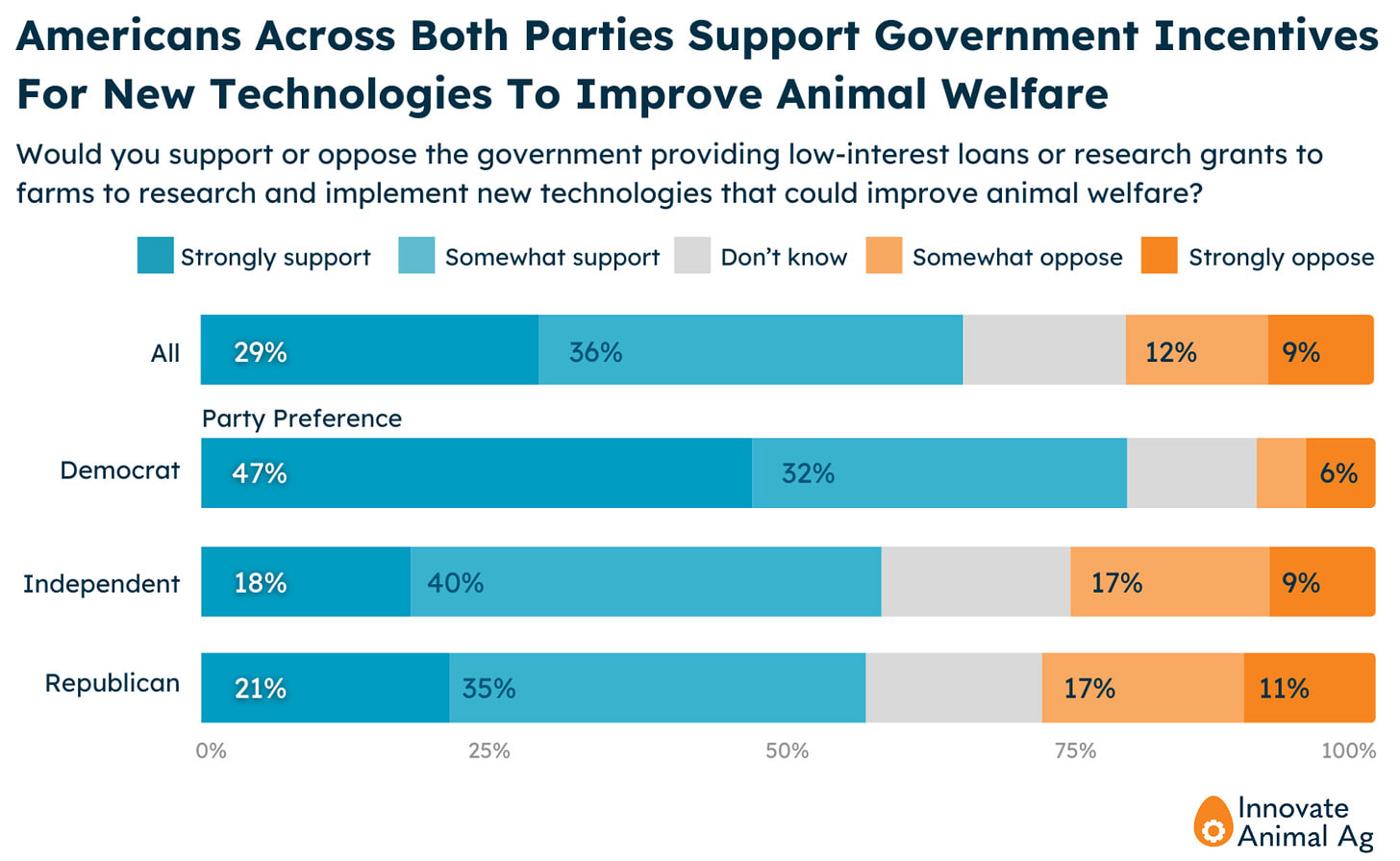

But people clearly do care about having a better food system—that’s why proposals like Proposition 12 can be passed by majority vote. According to polling, 65% of Americans would support government incentives for animal welfare-improving technologies, including majorities in both political parties. Given that government funding explicitly supporting farm animal welfare is close to zero, it seems well-justified to raise funding levels at least proportionally to the extent that people care.

Welfare subsidies also have the benefit of helping rather than harming farmers. In our age of food abundance, it’s easy to forget how recently the question was “how can we ensure that we’ll have enough to eat?” rather than “how can we build a food system that aligns with our values?” Farmers are the ones entrusted with maintaining this abundance, and including them in the coalition would not only be politically expedient, but also cognizant of the importance of their mission.

For policymakers about to take power, there’s a clear opportunity here to lean into a cause that has broad support from the American public, helps American farmers, and can propel America's leadership in agricultural innovation. When we try to incentivize only with the “stick,” we create an antagonistic environment full of zero-sum battles. However, when we also incentivize with the “carrot,” we create an environment where everyone can rally behind a goal that we all share.

The Optimist's Barn is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Upgrade to paid

Executive summary: Government subsidies for farm animal welfare improvements would be more effective and politically viable than traditional punitive policies, as they treat animal welfare as a public good that benefits all of society rather than just individual consumers.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.