by Trevor Chow, Basil Halperin, and J. Zachary Mazlish

In this post, we point out that short AI timelines would cause real interest rates to be high, and would do so under expectations of either unaligned or aligned AI. However, 30- to 50-year real interest rates are low. We argue that this suggests one of two possibilities:

- Long(er) timelines. Financial markets are often highly effective information aggregators (the “efficient market hypothesis”), and therefore real interest rates accurately reflect that transformative AI is unlikely to be developed in the next 30-50 years.

- Market inefficiency. Markets are radically underestimating how soon advanced AI technology will be developed, and real interest rates are therefore too low. There is thus an opportunity for philanthropists to borrow while real rates are low to cheaply do good today; and/or an opportunity for anyone to earn excess returns by betting that real rates will rise.

In the rest of this post we flesh out this argument.

- Both intuitively and under every mainstream economic model, the “explosive growth” caused by aligned AI would cause high real interest rates.

- Both intuitively and under every mainstream economic model, the existential risk caused by unaligned AI would cause high real interest rates.

- We show that in the historical data, indeed, real interest rates have been correlated with future growth.

- Plugging the Cotra probabilities for AI timelines into the baseline workhorse model of economic growth implies substantially higher real interest rates today.

- In particular, we argue that markets are decisively rejecting the shortest possible timelines of 0-10 years.

- We argue that the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) is a reasonable prior, and therefore one reasonable interpretation of low real rates is that since markets are simply not forecasting short timelines, neither should we be forecasting short timelines.

- Alternatively, if you believe that financial markets are wrong, then you have the opportunity to (1) borrow cheaply today and use that money to e.g. fund AI safety work; and/or (2) earn alpha by betting that real rates will rise.

An order-of-magnitude estimate is that, if markets are getting this wrong, then there is easily $1 trillion lying on the table in the US treasury bond market alone – setting aside the enormous implications for every other asset class.

Interpretation. We view our argument as the best existing outside view evidence on AI timelines – but also as only one model among a mixture of models that you should consider when thinking about AI timelines. The logic here is a simple implication of a few basic concepts in orthodox economic theory and some supporting empirical evidence, which is important because the unprecedented nature of transformative AI makes “reference class”-based outside views difficult to construct. This outside view approach contrasts with, and complements, an inside view approach, which attempts to build a detailed structural model of the world to forecast timelines (e.g. Cotra 2020; see also Nostalgebraist 2022).

Outline. If you want a short version of the argument, sections I and II (700 words) are the heart of the post. Additionally, the section titles are themselves summaries, and we use text formatting to highlight key ideas.

I. Long-term real rates would be high if the market was pricing advanced AI

Real interest rates reflect, among other things:

- Time discounting, which includes the probability of death

- Expectations of future economic growth

This claim is compactly summarized in the “Ramsey rule” (and the only math that we will introduce in this post), a version of the “Euler equation” that in one form or another lies at the heart of every theory and model of dynamic macroeconomics:

where:

- is the real interest rate over a given time horizon

- is time discounting over that horizon

- is a (positive) preference parameter reflecting how much someone cares about smoothing consumption over time

- is the growth rate

(Internalizing the meaning of these Greek letters is wholly not necessary.)

While more elaborate macroeconomic theories vary this equation in interesting and important ways, it is common to all of these theories that the real interest rate is higher when either (1) the time discount rate is high or (2) future growth is expected to be high.

We now provide some intuition for these claims.

Time discounting and mortality risk. Time discounting refers to how much people discount the future relative to the present, which captures both (i) intrinsic preference for the present relative to the future and (ii) the probability of death.

The intuition for why the probability of death raises the real rate is the following. Suppose we expect with high probability that humanity will go extinct next year. Then there is no reason to save today: no one will be around to use the savings. This pushes up the real interest rate, since there is less money available for lending.

Economic growth. To understand why higher economic growth raises the real interest rate, the intuition is similar. If we expect to be wildly rich next year, then there is also no reason to save today: we are going to be tremendously rich, so we might as well use our money today while we’re still comparatively poor.

(For the formal math of the Euler equation, Baker, Delong, and Krugman 2005 is a useful reference. The core intuition is that either mortality risk or the prospect of utopian abundance reduces the supply of savings, due to consumption smoothing logic, which pushes up real interest rates.)

Transformative AI and real rates. Transformative AI would either raise the risk of extinction (if unaligned), or raise economic growth rates (if aligned).

Therefore, based on the economic logic above, the prospect of transformative AI – unaligned or aligned – will result in high real interest rates. This is the key claim of this post.

As an example in the aligned case, Davidson (2021) usefully defines AI-induced “explosive growth” as an increase in growth rates to at least 30% annually. Under a baseline calibration where and , and importantly assuming growth rates are known with certainty, the Euler equation implies that moving from 2% growth to 30% growth would raise real rates from 3% to 31%!

For comparison, real rates in the data we discuss below have never gone above 5%.

(In using terms like “transformative AI” or “advanced AI”, we refer to the cluster of concepts discussed in Yudkowsky 2008, Bostrom 2014, Cotra 2020, Carlsmith 2021, Davidson 2021, Karnofsky 2022, and related literature: AI technology that precipitates a transition comparable to the agricultural or industrial revolutions.)

II. But: long-term real rates are low

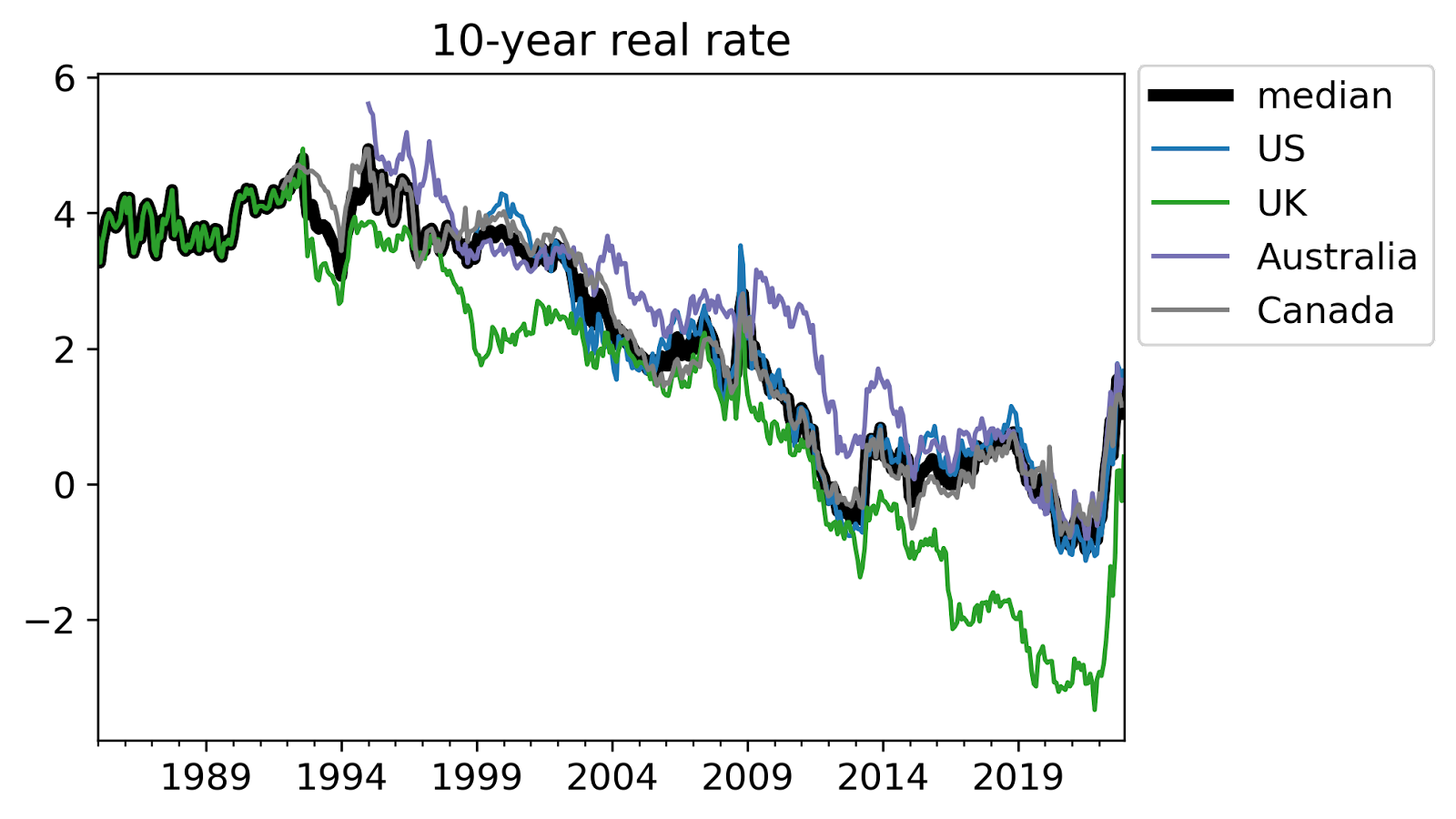

The US 30-year real interest rate ended 2022 at 1.6%. Over the full year it averaged 0.7%, and as recently as March was below zero. Looking at a shorter time horizon, the US 10-year real interest rate is 1.6%, and similarly was below negative one percent as recently as March.

(Data sources used here are explained in section V.)

The UK in autumn 2021 sold a 50-year real bond with a -2.4% rate at the time. Real rates on analogous bonds in other developed countries in recent years have been similarly low/negative for the longest horizons available. Austria has a 100-year nominal bond – being nominal should make its rate higher due to expected inflation – with yields less than 3%.

Thus the conclusion previewed above: financial markets, as evidenced by real interest rates, are not expecting a high probability of either AI-induced growth acceleration or elevated existential risk, on at least a 30-50 year time horizon.

III. Uncertainty, takeoff speeds, inequality, and stocks

In this section we briefly consider some potentially important complications.

Uncertainty. The Euler equation and the intuition described above assumed certainty about AI timelines, but taking into account uncertainty does not change the core logic. With uncertainty about the future economic growth rate, then the real interest rate reflects the expected future economic growth rate, where importantly the expectation is taken over the risk-neutral measure: in brief, probabilities of different states are reweighted by their marginal utility. We return to this in our quantitative model below.

Takeoff speeds. Nothing in the logic above relating growth to real rates depends on slow vs. fast takeoff speed; the argument can be reread under either assumption and nothing changes. Likewise, when considering the case of aligned AI, rates should be elevated whether economic growth starts to rise more rapidly before advanced AI is developed or only does so afterwards. What matters is that GDP – or really, consumption – ends up high within the time horizon under consideration. As long as future consumption will be high within the time horizon, then there is less motive to save today (“consumption smoothing”), pushing up the real rate.

Inequality. The logic above assumed that the development of transformative AI affects everyone equally. This is a reasonable assumption in the case of unaligned AI, where it is thought that all of humanity will be evaporated. However, when considering aligned AI, it may be thought that only some will benefit, and therefore real interest rates will not move much: if only an elite Silicon Valley minority is expected to have utopian wealth next year, then everyone else may very well still choose to save today.

It is indeed the case that inequality in expected gains from transformative AI would dampen the impact on real rates, but this argument should not be overrated. First, asset prices can be crudely thought of as reflecting a wealth-weighted average across investors. Even if only an elite minority becomes fabulously wealthy, it is their desire for consumption smoothing which will end up dominating the determination of the real rate. Second, truly transformative AI leading to 30%+ economy-wide growth (“Moore’s law for everything”) would not be possible without having economy-wide benefits.

Stocks. One naive objection to the argument here would be the claim that real interest rates sound like an odd, arbitrary asset price to consider; certainly stock prices are the asset price that receive the most media attention.

In appendix 1, we explain that the level of the real interest rate affects every asset price: stocks for instance reflect the present discounted value of future dividends; and real interest rates determine the discount rate used to discount those future dividends. Thus, if real interest rates are ‘wrong’, every asset price is wrong. If real interest rates are wrong, a lot of money is on the table, a point to which we return in section X.

We also argue that stock prices in particular are not a useful indicator of market expectations of AI timelines. Above all, high stock prices of chipmakers or companies like Alphabet (parent of DeepMind) could only reflect expectations for aligned AI and could not be informative of the risk of unaligned AI. Additionally, as we explain further in the appendix, aligned AI could even lower equity prices, by pushing up discount rates.

IV. Historical data on interest rates supports the theory: preliminaries

In section I, we gave theoretical intuition for why higher expected growth or higher existential risk would result in higher interest rates: expectations for such high growth or mortality risk would lead people to want to save less and borrow more today. In this section and the next two, we showcase some simple empirical evidence that the predicted relationships hold in the available data.

Measuring real rates. To compare historical real interest rates to historical growth, we need to measure real interest rates.

Most bonds historically have been nominal, where the yield is not adjusted for changes in inflation. Therefore, the vast majority of research studying real interest rates starts with nominal interest rates, attempts to construct an estimate of expected inflation using some statistical model, and then subtracts this estimate of expected inflation from the nominal rate to get an estimated real interest rate. However, constructing measures of inflation expectations is extremely difficult, and as a result most papers in this literature are not very informative.

Additionally, most bonds historically have had some risk of default. Adjusting for this default premium is also extremely difficult, which in particular complicates analysis of long-run interest rate trends.

The difficulty in measuring real rates is one of the main causes, in our view, of Tyler Cowen’s Third Law: “all propositions about real interest rates are wrong”. Throughout this piece, we are badly violating this (Gödelian) Third Law. In appendix 2, we expand on our argument that the source of Tyler’s Third Law is measurement issues in the extant literature, together with some separate, frequent conceptual errors.

Our approach. We take a more direct approach.

Real rates. For our primary analysis, we instead use market real interest rates from inflation-linked bonds. Because we use interest rates directly from inflation-linked bonds – instead of constructing shoddy estimates of inflation expectations to use with nominal interest rates – this approach avoids the measurement issue just discussed (and, we argue, allows us to escape Cowen’s Third Law).

To our knowledge, prior literature has not used real rates from inflation-linked bonds only because these bonds are comparatively new. Using inflation-linked bonds confines our sample to the last ~20 years in the US, the last ~30 in the UK/Australia/Canada. Before that, inflation-linked bonds didn’t exist. Other countries have data for even fewer years and less liquid bond markets.

(The yields on inflation-linked bonds are not perfect measures of real rates, because of risk premia, liquidity issues, and some subtle issues with the way these securities are structured. You can build a model and attempt to strip out these issues; here, we will just use the raw rates. If you prefer to think of these empirics as “are inflation-linked bond yields predictive of future real growth” rather than “are real rates predictive of future real growth”, that interpretation is still sufficient for the logic of this post.)

Nominal rates. Because there are only 20 or 30 years of data on real interest rates from inflation-linked bonds, we supplement our data by also considering unadjusted nominal interest rates. Nominal interest rates reflect real interest rates plus inflation expectations, so it is not appropriate to compare nominal interest rates to real GDP growth.

Instead, analogously to comparing real interest rates to real GDP growth, we compare nominal interest rates to nominal GDP growth. The latter is not an ideal comparison under economic theory – and inflation variability could swamp real growth variability – but we argue that this approach is simple and transparent.

Looking at nominal rates allows us to have a very large sample of countries for many decades: we use OECD data on nominal rates available for up to 70 years across 39 countries.

V. Historical data on interest rates supports the theory: graphs

The goal of this section is to show that real interest rates have correlated with future real economic growth, and secondarily, that nominal interest rates have correlated with future nominal economic growth. We also briefly discuss the state of empirical evidence on the correlation between real rates and existential risk.

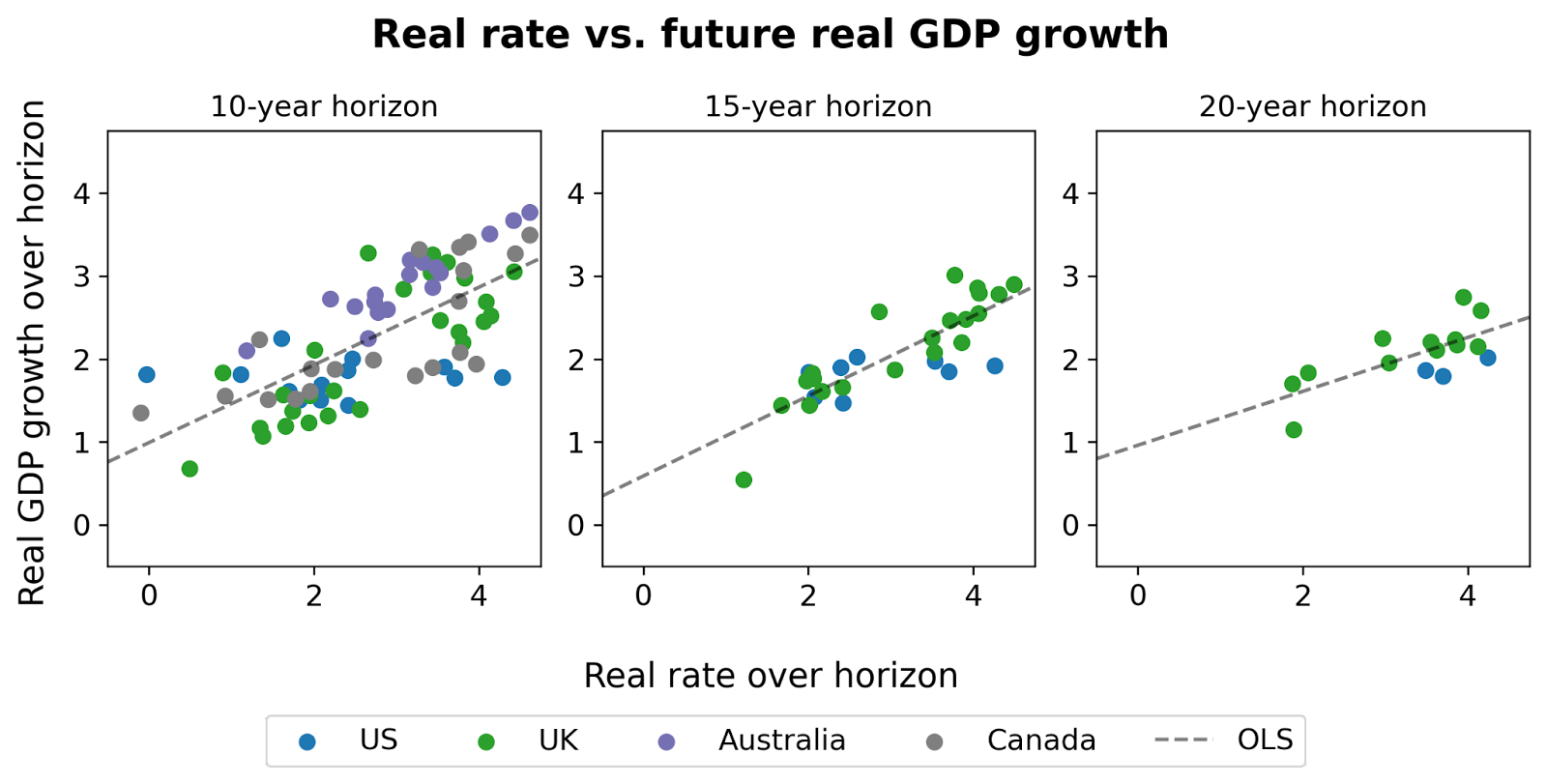

Real rates vs. real growth. A first cut at the data suggests that, indeed, higher real rates today predict higher real growth in the future:

To see how to read these graphs, take the left-most graph (“10-year horizon”) for example. The x-axis shows the level of the real interest rate, as reflected on 10-year inflation linked bonds. The y-axis shows average real GDP growth over the following 10 years.

The middle and right hand graphs show the same, at the 15-year and 20-year horizons. The scatter plot shows all available data for the US (since 1999), the UK (since 1985), Australia (since 1995), and Canada (since 1991). (Data for Australia and Canada is only available at the 10-year horizon, and comes from Augur Labs.)

Eyeballing the figure, there appears to be a strong relationship between real interest rates today and future economic growth over the next 10-20 years.

To our knowledge, this simple stylized fact is novel.

Caveats. “Eyeballing it” is not a formal econometric method; but, this is a blog post not a journal article (TIABPNAJA). We do not perform any formal statistical tests here, but we do want to acknowledge some important statistical points and other caveats.

First, the data points in the scatter plot are not statistically independent: real rates and growth are both persistent variables; the data points contain overlapping periods; and growth rates in these four countries are correlated. These issues are evident even from eyeballing the time series. Second, of course this relationship is not causally identified: we do not have exogenous variation in real growth rates. (If you have ideas for identifying the causal effect of higher real growth expectations on real rates, we would love to discuss with you.)

Relatedly, many other things are changing in the world which are likely to affect real rates. Population growth is slowing, retirement is lengthening, the population is aging. But under AI-driven “explosive” growth – again say 30%+ annual growth, following the excellent analysis of Davidson (2021) – then, we might reasonably expect that this massive of an increase in the growth rate would drown out the impact of any other factors.

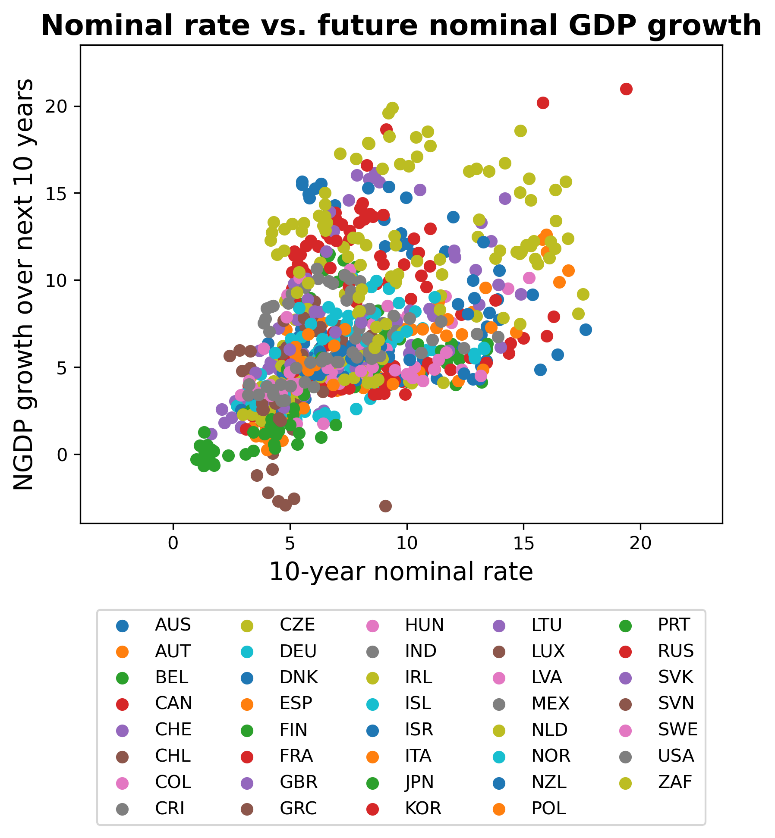

Nominal rates vs. nominal growth. Turning now to evidence from nominal interest rates, recall that the usefulness of this exercise is that while there only exists 20 or 30 years of data on real interest rates for two countries, there is much more data on nominal interest rates.

We simply take all available data on 10-year nominal rates from the set of 39 OECD countries since 1954. The following scatterplot compares the 10-year nominal interest versus nominal GDP growth over the succeeding ten years by country:

Again, there is a strong positive – if certainly not perfect – relationship. (For example, the outlier brown dots at the bottom of the graph are Greece, whose high interest rates despite negative NGDP growth reflect high default risk during an economic depression.)

The same set of nontrivial caveats apply to this analysis as above.

We consider this data from nominal rates to be significantly weaker evidence than the evidence from real rates, but corroboration nonetheless.

Backing out market-implied timelines. Taking the univariate pooled OLS results from the real rate data far too seriously, the fact that the 10-year real rate in the US ended 2022 at 1.6% would predict average annual real GDP growth of 2.6% over the next 10 years in the US; the analogous interest rate of -0.2% in the UK would predict 0.7% annual growth over the next 10 years in the UK. Such growth rates, clearly, are not compatible with the arrival of transformative aligned AI within this horizon.

VI. Empirical evidence on real rates and mortality risk

We have argued that in the theory, real rates should be higher in the face of high economic growth or high mortality risk; empirically, so far, we have only shown a relationship between real rates and growth, but not between real rates and mortality.

Showing that real rates accurately reflect changes in existential risk is very difficult, because there is no word-of-god measurement of how existential risk has evolved over time.

We would be very interested in pursuing new empirical research examining “asset pricing under existential risk”. In appendix 3, we perform a scorched-earth literature review and find essentially zero existing empirical evidence on real rates and existential risks.

Disaster risk. In particular, the extant literature does not study existential risks but instead “merely” disaster risks, under which real assets are devastated but humanity is not exterminated. Disaster risks do not necessarily raise real rates – indeed, such risks are thought to lower real rates due to precautionary savings. That notwithstanding, some highlights of the appendix review include a small set of papers finding that individuals with a higher perceived risk of nuclear conflict during the Cold War saved less, as well as a paper noting that equities which were headquartered in cities more likely to be targeted by Soviet missiles did worse during the Cuban missile crisis (see also). Our assessment is that these and the other available papers on disaster risks discussed in the appendix have severe limitations for the purposes here.

Individual mortality risk. We judge that the best evidence on this topic comes instead from examining the relationship between individual mortality risk and savings/investment behavior. The logic we provided was that if humanity will be extinct next year, then there is no reason to save, pushing up the real rate. Similar logic says that at the individual level, a higher risk of death for any reason should lead to lower savings and less investment in human capital. Examples of lower savings at the individual level need not raise interest rates at the economy-wide level, but do provide evidence for the mechanism whereby extinction risk should lead to lower saving and thus higher interest rates.

One example comes from Malawi, where the provision of a new AIDS therapy caused a significant increase in life expectancy. Using spatial and temporal variation in where and when these therapeutics were rolled out, it was found that increased life expectancy results in more savings and more human capital investment in the form of education spending. Another experiment in Malawi provided information to correct pessimistic priors about life expectancy, and found that higher life expectancy directly caused more investment in agriculture and livestock.

A third example comes from testing for Huntington’s disease, a disease which causes a meaningful drop in life expectancy to around 60 years. Using variation in when people are diagnosed with Huntington’s, it has been found that those who learn they carry the gene for Huntington’s earlier are 30 percentage points less likely to finish college, which is a significant fall in their human capital investment.

Studying the effect on savings and real rates from increased life expectancy at the population level is potentially intractable, but would be interesting to consider further. Again, in our assessment, the best empirical evidence available right now comes from the research on individual “existential” risks and suggests that real rates should increase with existential risk.

VII. Plugging the Cotra probabilities into a simple quantitative model of real interest rates predicts very high rates

Section VI used historical data to go from the current real rate to a very crude market-implied forecast of growth rates; in this section, we instead use a model to go from existing forecasts of AI timelines to timeline-implied real rates. We aim to show that under short AI timelines, real interest rates would be unrealistically elevated.

This is a useful exercise for three reasons. First, the historical data is only able to speak to growth forecasts, and therefore only able to provide a forecast under the possibly incorrect assumption of aligned AI. Second, the empirical forecast assumes a linear relationship between the real rate and growth, which may not be reasonable for a massive change caused by transformative AI. Third and quite important, the historical data cannot transparently tell us anything about uncertainty and the market’s beliefs about the full probability distribution of AI timelines.

We use the canonical (and nonlinear) version of the Euler equation – the model discussed in section I – but now allow for uncertainty on both how soon transformative AI will be developed and whether or not it will be aligned. The model takes as its key inputs (1) a probability of transformative AI each year, and (2) a probability that such technology is aligned.

The model is a simple application of the stochastic Euler equation under an isoelastic utility function. We use the following as a baseline, before considering alternative probabilities:

- We use smoothed Cotra (2022) probabilities for transformative AI over the next 30 years: a 2% yearly chance until 2030, a 3% yearly chance through 2036, and a 4% yearly chance through 2052.

- We use the FTX Future Fund’s median estimate of 15% for the probability that AI is unaligned conditional on the development of transformative AI.

- With the arrival of aligned AI, we use the Davidson (2020) assumption of 30% annual economic growth; with the arrival of unaligned AI, we assume human extinction. In the absence of the development of transformative AI, we assume a steady 1.8% growth rate.

- We calibrate the pure rate of subjective time preference to 0.01 and the consumption smoothing parameter (i.e. inverse of the elasticity of intertemporal substitution) as 1, following the economic literature.

Thus, to summarize: by default, GDP grows at 1.8% per year. Every year, there is some probability (based on Cotra) that transformative AI is developed. If it is developed, there is a 15% probability the world ends, and an 85% chance GDP growth jumps to 30% per year.

We have built a spreadsheet here that allows you to tinker with the numbers yourself, such as adjusting the growth rate under aligned AI, to see what your timelines and probability of alignment would imply for the real interest rate. (It also contains the full Euler equation formula generating the results, for those who want the mathematical details.) We first estimate real rates under the baseline calibration above, before considering variations in the critical inputs.

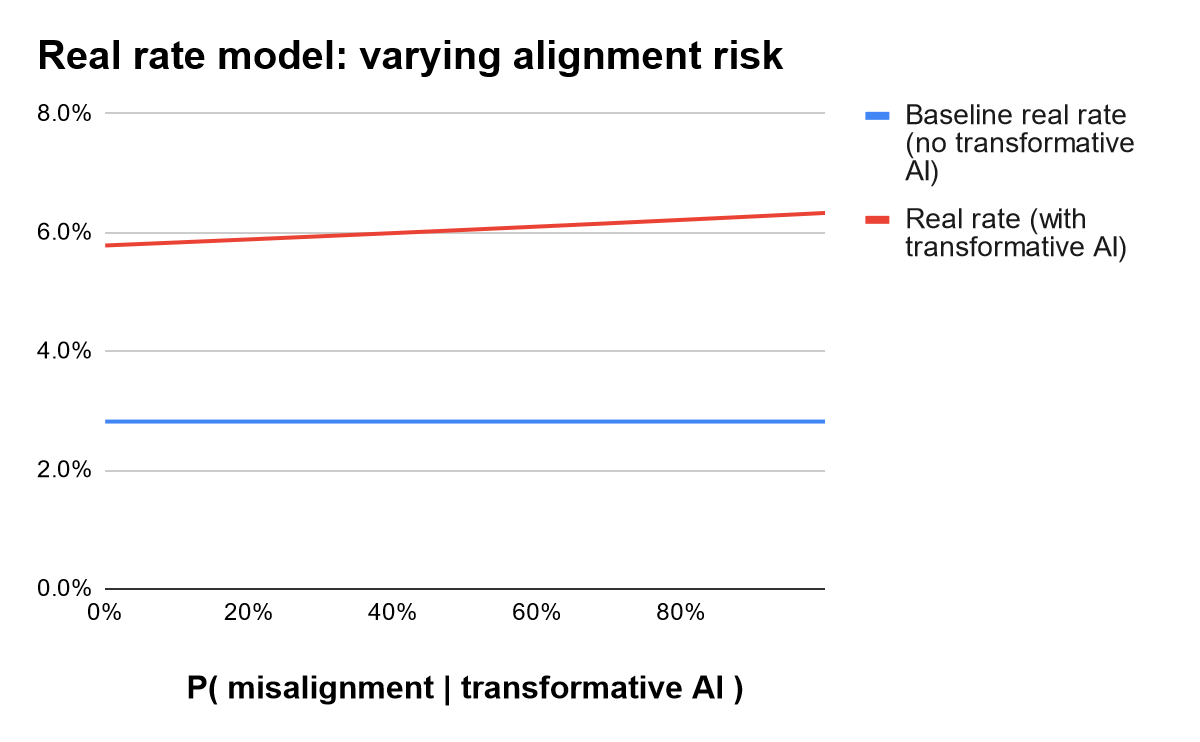

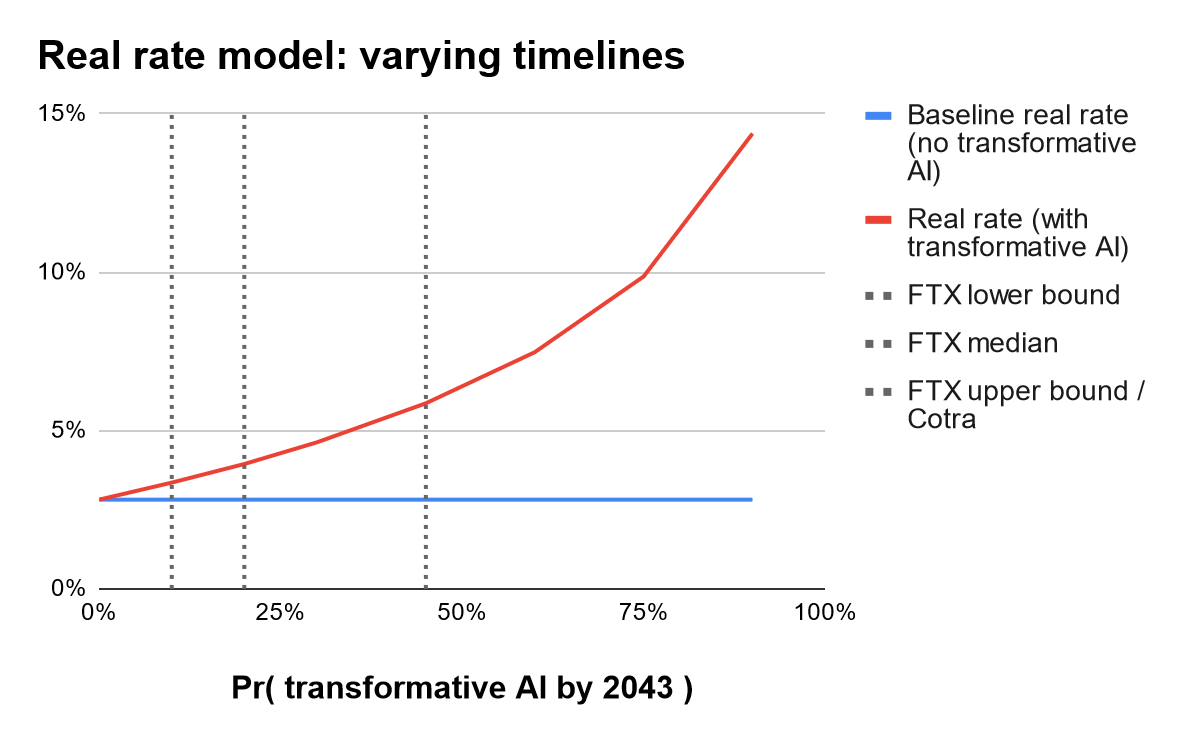

Baseline results. The model predicts that under zero probability of transformative AI, the real rate at any horizon would be 2.8%. In comparison, under the baseline calibration just described based on Cotra timelines, the real rate at a 30-year horizon would be pushed up to 5.9% – roughly three percentage points higher.

For comparison, the 30-year real rate in the US is currently 1.6%.

While the simple Euler equation somewhat overpredicts the level of the real interest rate even under zero probability of transformative AI – the 2.8% in the model versus the 1.6% in the data – this overprediction is explainable by the radical simplicity of the model that we use and is a known issue in the literature. Adding other factors (e.g. precautionary savings) to the model would lower the level. Changing the level does not change its directional predictions, which help quantitatively explain the fall in real rates over the past ~30 years.

Therefore, what is most informative is the three percentage point difference between the real rate under Cotra timelines (5.9%) versus under no prospect of transformative AI (2.8%): Cotra timelines imply real interest rates substantially higher than their current levels.

Now, from this baseline estimate, we can also consider varying the key inputs.

Varying assumptions on P(misaligned|AGI). First consider changing the assumption that advanced AI is 15% likely to be unaligned (conditional on the development of AGI). Varying this parameter does not have a large impact: moving from 0% to 100% probability of misalignment raises the model’s predicted real rate from 5.8% only to 6.3%.

Varying assumptions on timelines. Second, consider making timelines shorter or longer. In particular, consider varying the probability of development by 2043, which we use as a benchmark per the FTX Future Fund.

We scale the Cotra timelines up and down to vary the probability of development by 2043. (Specifically: we target a specific cumulative probability of development by 2043; and, following Cotra, if the annual probability up until 2030 is , then it is in the subsequent seven years up through 2036, and it is in the remaining years of the 30-year window.)

As the next figure shows and as one might expect, shorter AI timelines have a very large impact on the model’s estimate for the real rate.

- The original baseline parameterization from Cotra corresponds to the FTX Future Fund “upper threshold” of a 45% chance of development by 2043, which generated the 3 percentage point increase in the 30-year real rate discussed above.

- The Future Fund’s median of a 20% probability by 2043 generates a 1.1 percentage point increase in the 30-year real rate.

- The Future Fund’s “lower threshold” of a 10% probability by 2043 generates a 0.5 percentage point increase in the real rate.

These results strongly suggest that any timeline shorter than or equal to the Cotra timeline is not being expected by financial markets.

VIII. Markets are decisively rejecting the shortest possible timelines

While it is not possible to back out exact numbers for the market’s implicit forecast for AI timelines, it is reasonable to say that the market is decisively rejecting – i.e., putting very low probability on – the development of transformative AI in the very near term, say within the next ten years.

Consider the following examples of extremely short timelines:

- Five year timelines: With a 50% probability of transformative AI by 2027, and the same yearly probability thereafter, the model predicts 13.0pp higher 30-year real rates today!

- Ten year timelines: With a 50% probability of transformative AI by 2032, and the same yearly probability thereafter, the model predicts 6.5pp higher 30-year real rates today.

Real rate movements of these magnitudes are wildly counterfactual. As previously noted, real rates in the data used above have never gone above even 5%.

Stagnation. As a robustness check, in the configurable spreadsheet we allow you to place some yearly probability on the economy stagnating and growing at 0% per year from thereon. Even with a 20% chance of stagnation by 2053 (higher than realistic), under Cotra timelines, the model generates a 2.1% increase in 30-year rates.

Recent market movements. Real rates have increased around two percentage points since the start of 2022, with the 30-year real rate moving from -0.4% to 1.6%, approximately the pre-covid level. This is a large enough move to merit discussion. While this rise in long-term real rates could reflect changing market expectations for timelines, it seems much more plausible that high inflation, the Russia-Ukraine war, and monetary policy tightening have together worked to drive up short-term real rates and the risk premium on long-term real rates.

IX. Financial markets are the most powerful information aggregators produced by the universe (so far)

Should we update on the fact that markets are not expecting very short timelines?

Probably!

As a prior, we think that market efficiency is reasonable. We do not try to provide a full defense of the efficient markets hypothesis (EMH) in this piece given that it has been debated ad nauseum elsewhere, but here is a scaffolding of what such an argument would look like.

Loosely, the EMH says that the current price of any security incorporates all public information about it, and as such, you should not expect to systematically make money by trading securities.

This is simply a no-arbitrage condition, and certainly no more radical than supply and demand: if something is over- or under-priced, you’ll take action based on that belief until you no longer believe it. In other words, you’ll buy and sell it until you think the price is right. Otherwise, there would be an unexploited opportunity for profit that was being left on the table, and there are no free lunches when the market is in equilibrium.

As a corollary, the current price of a security should be the best available risk-adjusted predictor of its future price. Notice we didn’t say that the price is equal to the “correct” fundamental value. In fact, the current price is almost certainly wrong. What we did say is that it is the best guess, i.e. no one knows if it should be higher or lower.

Testing this hypothesis is difficult, in the same way that testing any equilibrium condition is difficult. Not only is the equilibrium always changing, there is also a joint hypothesis problem which Fama (1970) outlined: comparing actual asset prices to “correct” theoretical asset prices means you are simultaneously testing whatever asset pricing model you choose, alongside the EMH.

In this sense, it makes no sense to talk about “testing” the EMH. Rather, the question is how quickly prices converge to the limit of market efficiency. In other words, how fast is information diffusion? Our position is that for most things, this is pretty fast!

Here are a few heuristics that support our position:

- For our purposes, the earlier evidence on the link between real rates and growth is a highly relevant example of market efficiency.

- There are notable examples of markets seeming to be eerily good at forecasting hard-to-anticipate events:

- In the wake of the Challenger explosion, despite no definitive public information being released, the market seems to have identified which firm was responsible.

- Economist Armen Alchian observed that the stock price of lithium producers spiked 461% following the public announcement of the first hydrogen bomb tests in 1954, while the prices of producers of other radioactive metals were flat. He circulated a paper within RAND, where he was working, identifying lithium as the material used in the tests, before the paper was suppressed by leadership who were apparently aware that indeed lithium was used. The market was prescient even though zero public information was released about lithium’s usage.

Remember: if real interest rates are wrong, all financial assets are mispriced. If real interest rates “should” rise three percentage points or more, that is easily hundreds of billions of dollars worth of revaluations. It is unlikely that sharp market participants are leaving billions of dollars on the table.

X. If markets are not efficient, you could be earning alpha and philanthropists could be borrowing

While our prior in favor of efficiency is fairly strong, the market could be currently failing to anticipate transformative AI, due to various limits to arbitrage.

However, if you do believe the market is currently wrong about the probability of short timelines, then we now argue there are two courses of action you should consider taking:

- Bet on real rates rising (“get rich or die trying”)

- Borrow today, including in order to fund philanthropy (“impatient philanthropy”)

1. Bet on real rates rising (“get rich or die trying”)

Under the logic argued above, if you genuinely believe that AI timelines are short, then you should consider putting your money where your mouth is: bet that real rates will rise when the market updates, and potentially earn a lot of money if markets correct. Shorting (or going underweight) government debt is the simplest way of expressing this view.

Indeed, AI safety researcher Paul Christiano has written publicly that he is (or was) short 30-year government bonds.

If short timelines are your true belief in your heart of hearts, and not merely a belief in a belief, then you should seriously consider how much money you could earn here and what you could do with those resources.

Implementing the trade. For retail investors, betting against treasuries via ETFs is perhaps simplest. Such trades can be done easily with retail brokers, like Schwab.

(i) For example, one could simply short the LTPZ ETF, which holds long-term real US government debt (effective duration: 20 years).

(ii) Alternatively, if you would prefer to avoid engaging in shorting yourself, there are ETFs which will do the shorting for you, with nominal bonds: TBF is an ETF which is short 20+ year treasuries (duration: 18 years); TBT is the same, but levered 2x; and TTT is the same, but levered 3x. There are a number of other similar options. Because these ETFs do the shorting for you, all you need to do is purchase shares of the ETFs.

Back of the envelope estimate. A rough estimate of how much money is on the table, just from shorting the US treasury bond market alone, suggests there is easily $1 trillion in value at stake from betting that rates will rise.

- In response to a 1 percentage point rise in interest rates, the price of a bond falls in percentage terms by its “duration”, to a first-order approximation.

- The average value-weighted duration of (privately-held) US treasuries is approximately 4 years.

- So, to a first-order approximation, if rates rise by 3 percentage points, then the value of treasuries will fall by 12% (that is, 3*4).

- The market cap of (privately-held) treasuries is approximately $17 trillion.

- Thus, if rates rise by 3 percentage points, then the total value of treasuries can be expected to fall by $2.04 trillion (that is, 12%*17 trillion).

- Slightly more than half (55%) of the interest rate sensitivity of the treasury market comes from bonds with maturity beyond 10 years. Assuming that the 3 percentage point rise occurs only at this horizon, and rounding down, we arrive at the $1 trillion estimate.

Alternatively, returning to the LTPZ ETF with its duration of 20 years, a 3 percentage point rise in rates would cause its value to fall by 60%. Using the 3x levered TTT with duration of 18 years, a 3 percentage point rise in rates would imply a mouth-watering cumulative return of 162%.

While fully fleshing out the trade analysis is beyond the scope of this post, this illustration gives an idea of how large the possibilities are.

The alternative to this order-of-magnitude estimate would be to build a complete bond pricing model to estimate more precisely the expected returns of shorting treasuries. This would need to take into account e.g. the convexity of price changes with interest rate movements, the varied maturities of outstanding bonds, and the different varieties of instruments issued by the Treasury. Further refinements would include trading derivatives (e.g. interest rate futures) instead of shorting bonds directly, for capital efficiency, and using leverage to increase expected returns.

Additionally, the analysis could be extended beyond the US government debt market, again since changes to real interest rates would plausibly impact the price of every asset: stocks, commodities, real estate, everything.

(If you would be interested in fully scoping out possible trades, we would be interested in talking.)

Trade risk and foom risk. We want to be clear that – unless you are risk neutral, or can borrow without penalty at the risk-free rate, or believe in short timelines with 100% probability – then such a bet would not be a free lunch: this is not an “arbitrage” in the technical sense of a risk-free profit. One risk is that the market moves in the other direction in the short term, before correcting, and that you are unable to roll over your position for liquidity reasons.

The other risk that could motivate not making this bet is the risk that the market – for some unspecified reason – never has a chance to correct, because (1) transformative AI ends up unaligned and (2) humanity’s conversion into paperclips occurs overnight. This would prevent the market from ever “waking up”.

However, to be clear, expecting this specific scenario requires both:

- Buying into specific stories about how takeoff will occur: specifically, Yudkowskian foom-type scenarios with fast takeoff.

- Having a lot of skepticism about the optimization forces pushing financial markets towards informational efficiency.

You should be sure that your beliefs are actually congruent with these requirements, if you want to refuse to bet that real rates will rise. Additionally, we will see that the second suggestion in this section (“impatient philanthropy”) is not affected by the possibility of foom scenarios.

2. Borrow today, including in order to fund philanthropy (“impatient philanthropy”)

If prevailing interest rates are lower than your subjective discount rate – which is the case if you think markets are underestimating prospects for transformative AI – then simple cost-benefit analysis says you should save less or even borrow today.

An illustrative example. As an extreme example to illustrate this argument, imagine that you think that there is a 50% chance that humanity will be extinct next year, and otherwise with certainty you will have the same income next year as you do this year. Suppose the market real interest rate is 0%. That means that if you borrow $10 today, then in expectation you only need to pay $5 off, since 50% of the time you expect to be dead.

It is only if the market real rate is 100% – so that your $10 loan requires paying back $20 next year, or exactly $10 in expectation – that you are indifferent about borrowing. If the market real rate is less than 100%, then you want to borrow. If interest rates are “too low” from your perspective, then on the margin this should encourage you to borrow, or at least save less.

Note that this logic is not affected by whether or not the market will “correct” and real rates will rise before everyone dies, unlike the logic above for trading.

Borrowing to fund philanthropy today. While you may want to borrow today simply to fund wild parties, a natural alternative is: borrow today, locking in “too low” interest rates, in order to fund philanthropy today. For example: to fund AI safety work.

We can call this strategy “impatient philanthropy”, in analogy to the concept of “patient philanthropy”.

This is not a call for philanthropists to radically rethink their cost-benefit analyses. Instead, we merely point out: ensure that your financial planning properly accounts for any difference between your discount rate and the market real rate at which you can borrow. You should not be using the market real rate to do your financial planning. If you have a higher effective discount rate due to your AI timelines, that could imply that you should be borrowing today to fund philanthropic work.

Relationship to impatient philanthropy. The logic here has a similar flavor to Phil Trammell’s “patient philanthropy” argument (Trammell 2021) – but with a sign flipped. Longtermist philanthropists with a zero discount rate, who live in a world with a positive real interest rate, should be willing to save all of their resources for a long time to earn that interest, rather than spending those resources today on philanthropic projects. Short-timeliners have a higher discount rate than the market, and therefore should be impatient philanthropists.

(The point here is not an exact analog to Trammell 2021, because the paper there considers strategic game theoretic considerations and also takes the real rate as exogenous; here, the considerations are not strategic and the endogeneity of the real rate is the critical point.)

XI. Conclusion: outside views vs. inside views & future work

We do not claim to have special technical insight into forecasting the likely timeline for the development of transformative artificial intelligence: we do not present an inside view on AI timelines.

However, we do think that market efficiency provides a powerful outside view for forecasting AI timelines and for making financial decisions. Based on prevailing real interest rates, the market seems to be strongly rejecting timelines of less than ten years, and does not seem to be placing particularly high odds on the development of transformative AI even 30-50 years from now.

We argue that market efficiency is a reasonable benchmark, and consequently, this forecast serves as a useful prior for AI timelines. If markets are wrong, on the other hand, then there is an enormous amount of money on the table from betting that real interest rates will rise. In either case, this market-based approach offers a useful framework: either for forecasting timelines, or for asset allocation.

Opportunities for future work. We could have put 1000 more hours into the empirical side or the model, but, TIABPNAJA. Future work we would be interested in collaborating on or seeing includes:

- More careful empirical analyses of the relationship between real rates and growth. In particular, (1) analysis of data samples with larger variation in growth rates (e.g. with the Industrial Revolution, China or the East Asian Tigers), where a credible measure of real interest rates can be used; and (2) causally identified estimates of the relationship between real rates and growth, rather than correlations. Measuring historical real rates is the key challenge, and the main reason why we have not tried to address these here.

- Any empirical analysis of how real rates vary with changing existential risk. Measuring changes in existential risk is the key challenge.

- Alternative quantitative models on the relationship between real interest rates and growth/x-risk with alternative preference specifications, incomplete markets, or disaster risk.

- Tests of market forecasting ability at longer time horizons for any outcome of significance; and comparisons of market efficiency at shorter versus longer time horizons.

- Creation of sufficiently-liquid genuine market instruments for directly measuring outcomes we care about like long-horizon GDP growth: e.g. GDP swaps, GDP-linked bonds, or binary GDP prediction markets. (We emphasize market instruments to distinguish from forecasting platforms like Metaculus or play-money sites like Manifold Markets where the forceful logic of financial market efficiency simply does not hold.)

- An analysis of the most capital-efficient way to bet on short AI timelines and the possible expected returns (“the greatest trade of all time”).

- Analysis of the informational content of infinitely-lived assets: e.g. the discount rates embedded in land prices and rental contracts. There is an existing literature related to this topic: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

- This literature estimates risky, nominal discount rates embedded in rental contracts out as far as 1000 years, and finds surprisingly low estimates – certainly less than 10%. This is potentially extremely useful information, though this literature is not without caveats. Among many other things, we cannot have the presumption of informational efficiency in land/rental markets, unlike financial markets, due to severe frictions in these markets (e.g. inability to short sell).

Thanks especially to Leopold Aschenbrenner, Nathan Barnard, Jackson Barkstrom, Joel Becker, Daniele Caratelli, James Chartouni, Tamay Besiroglu, Joel Flynn, James Howe, Chris Hyland, Stephen Malina, Peter McLaughlin, Jackson Mejia, Laura Nicolae, Sam Lazarus, Elliot Lehrer, Jett Pettus, Pradyumna Prasad, Tejas Subramaniam, Karthik Tadepalli, Phil Trammell, and participants at ETGP 2022 for very useful conversations on this topic and/or feedback on drafts.

Update 1: we have now posted a comment summarising our responses to the feedback we have received so far.

Postscript

OpenAI’s ChatGPT model on what will happen to real rates if transformative AI is developed:

🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔🤔

Some framings you can use to interpret this post:

- “This blog post takes Fama seriously” [a la Mankiw-Romer-Weil]

- “The market-clearing price does not hate you nor does it love you” [a la Yudkowsky]

- “Existential risk and asset pricing” [a la Aschenbrenner 2020, Trammell 2021]

- “Get rich or hopefully don’t die trying” [a la 50 Cent]

- “You can short the apocalypse.” [contra Peter Thiel, cf Alex Tabarrok]

- “Tired: market monetarism. Inspired: market longtermism.” [a la Scott Sumner]

- “This is not not financial advice.” [a la the standard disclaimer]

Appendix 1. Against using stock prices to forecast AI timelines

Link to separate EA Forum post

Lots of the comments here are pointing at details of the markets and whether it's possible to profit off of knowing that transformative AI is coming. Which is all fine and good, but I think there's a simple way to look at it that's very illuminating.

The stock market is good at predicting company success because there are a lot of people trading in it who think hard about which companies will succeed, doing things like writing documents about those companies' target markets, products, and leadership. Traders who do a good job at this sort of analysis get more funds to trade with, which makes their trading activity have a larger impact on the prices.

Now, when you say that:

I think what you're claiming is that market prices are substantially controlled by traders who have a probability like that in their heads. Or traders who are following an algorithm which had a probability like that in the spreadsheet. Or something thing like that. Some sort of serious cognition, serious in the way that traders treat compan... (read more)

I find it hard to believe that the number of traders who have considered crazy future AI scenarios is negligible. New AI models, semiconductor supply chains, etc. have gotten lots of media and intellectual attention recently. Arguments about transformative AGI are public. Many people have incentives to look into them and think about their implications.

I don't think this post is decisive evidence against short timelines. But neither do I think it's a "trap" that relies on fully swallowing EMH. I think there're deeper issues to unpack here about why much of the world doesn't seem to put much weight on AGI coming any time soon.

Plenty of people at Jane Street that read LessWrong

Just a note on Jane Street in particular - nobody at Jane Street is making a potentially multi year bet on interest rates with Jane Street money. That's simply not in the category of things that Jane Street trades. If someone at Jane Street wanted to make betting on this a significant part of what they do, they'd have to leave and go elsewhere and find someone to give them at least hundreds of millions of dollars to make the bet.

Jane street even hosted a foom debate between between Hanson and yudkowsky iirc.

(I don’t think this is substantial evidence on the validity of original post)

Yeah, I'm also similarly sceptical that a highly publicised/discussed portion of one of the most hyped industries — one that borders on a buzzword at times — has not captured the attention or consideration of the market. Seems hard to imagine given the remarkably salient progress we've seen in 2022.

Definitely agree with this. Consider for instance how markets seemed to have reacted strangely / too slowly to the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, and then consider how much more familiar and predictable is the idea of a viral pandemic compared to the idea of unaligned AI:

Peter Thiel (in his "Optimistic Thought Experiment" essay about investing under anthropic shadow, which I analyzed in ... (read more)

The markets reacted appropriately to covid. Match the Dow to forecasters' and EAF's prognostications and you'll find that the markets moved in tandem with rational expectations.

https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/index/djia

The Dow plateaued in early January and crashed starting Feb 20th, tracking rational expectations and three weeks ahead of media/mass awareness, which only caught up around March 12th

Almost everyone I knew was concerned with the pandemic going global and dramatically disrupting our lives much sooner than Feb 20th. On January 26th, a post on the EA Forum, "Concerning the Recent 2019-Novel Coronavirus Outbreak", made the case we should be worried. By a few weeks later than that, everyone I know was already bracing for covid to hit the US. Looking back at my house Discord server, we had the "if we have to go weeks without leaving the house, is there anything we'd run out of? Let's buy it now" conversation February 6th (which is also when my Vox article about Covid published, in which I quote a source saying“Instead of deriding people’s fears about the Wuhan coronavirus, I would advise officials and reporters to focus more on the high likelihood that things will get worse and the not-so-small possibility that they will get much worse.”)

The late January SlateStarCodex open threads also typically contained 10-20 comments discussing the virus, linking prediction markets, debating the odds of more than 500k deaths and how people in various places should expect disruptions to their daily life. ("‘If everyone involved massively bungles absolutely everything, this w... (read more)

I'm not totally sure what I think the correct market behavior based on knowable information was, but it seems very hard to make the case that a large crash on Feb 20th is evidence of the markets moving "in tandem with rational expectations".

Here’s what I wrote in April 2020 on that topic:

“ A couple weeks ago, I started investigating the response, here and in the stock market, to COVID-19. I found that LessWrong's conversation took off about a week after the stock market started to crash. Given what we knew about COVID-19 prior to Feb. 20th, when the market first started to decline, I felt that the stock market's reaction was delayed. And of course, there'd been plenty of criticism of the response of experts and governments. But I was playing catch-up. I certainly was not screaming about COVID-19 until well after that time.

Today, I found the most detailed timeline I've seen of confirmed cases around the world. It goes day by day and country by country, from Jan. 13th to the end of March.

That timeline shows that Feb. 21st was the first date when at least 3 countries besides China had 10+ new confirmed cases in a single day (Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Iran).

That changes my interpretation of the stock market crash dramatically. Investors weren't failing to synthesize the early information or waiting for someone to yell "fire!" They were waiting to see confirmed international community spread, rather than just a few ca... (read more)

Yet the tweets you linked were from 2/16 and 2/17.

Rational expectations doesn't mean "the alarmists are always right," and EMH doesn't imply that no one can profit helping correct the market.

The tweets you linked demonstrate the confusion at the time. Robin thought that China would be overwhelmed with COVID in a few months, while the rest of the world would be closing contact. In fact the rest of the world got overwhelmed with COVID and crashed their economies in just one month, while China contained it and kept its economy rolling for another two years. Rational expectations would've incorporated views like Robin's, but not parroted them. A plateau from early January and crash on 2/20 isn't inconsistent with that.

It doesn't seem all that relevant to me whether traders have a probability like that in their heads. Whether they have a low probability or are not thinking about it, they're approximately leaving money on the table in a short-timelines world, which should be surprising. People have a large incentive to hunt for important probabilities they're ignoring.

Of course, there are examples (cf. behavioral economics) of systemic biases in markets. But even within behavioral economics, it's fairly commonly known that it's hard to find ongoing, large-scale biases in financial markets.

The claim in the post (which I think is very good) is that we should have a pretty strong prior against anything which requires positing massive market inefficiency on any randomly selected proposition where there is lots of money money on the table. This suggests that you should update away from very short timelines. There's no assumption that markets are a "mystical source of information" just that if you bet against them you almost always lose.

There's also a nice "put your money where you mouth is" takeaway from the post, which AFAIK few short timelines people are doing.

I think a fair number of market participants may have something like a probability estimate for transformative AI within five years and maybe even ten. (For example back when SoftBank was throwing money at everything that looked like a tech company, they justified it with a thesis something like "transformative AI is coming soon", and this would drive some other market participants to think about the truth of that thesis and its implications even if they wouldn't otherwise.) But I think you are right that basically no market participants have a probability estimate for transformative AI (or almost anything else) 30 years out; they aren't trying to make predictions that far out and don't expect to do significantly better than noise if they did try.

While this is a very valuable post, I don't think the core argument quite holds, for the following reasons:

- Markets work well as information aggregation algorithms when it is possible to profit a lot from being the first to realize something (e.g., as portrayed in "The Big Short" about the Financial Crisis).

- In this case, there is no way for the first movers to profit big. Sure, you can take your capital out of the market and spend it before the world ends (or everyone becomes super-rich post-singularity), but that's not the same as making a billion bucks.

- You can argue that one could take a short position on interest rates (e.g., in the form of a loan) if you believe that they will rise at some point, but that is a different bet from short timelines - what you're betting on then, is when the world will realize that timelines are short, since that's what it will take before many people choose to pull out of the market, and thus drive interest rates up. It is entirely possible to believe both that timelines are short, and that the world won't realize AI is near for a while yet, in which case you wouldn't do this. Furthermore, counterparty risks tend to get in the way of taking up

... (read more)This reasoning sounds pretty tortured to me.

First, should you really believe that the relatively small number of traders needed to move markets won't come to think AI is a really big deal, given that you think AI is a really big deal?

Second, if "the world won't realize AI is near for a while," you can still make money by following analogous strategies to those described in the post. You don't need the world to realize tomorrow.

I see that I wasn't being super clear above. Others in the comments have pointed to what I was trying to say here:

- The window between when "enough" traders realize that AI is near and when it arrives may be very short, meaning that even in the best case you'll only increase your wealth for a very short time by making this bet

- It is not clear how markets would respond if most traders started thinking that AI was near. They may focus on other opportunities that they believe are stronger than to go short interest rates (e.g., they may decide to invest in tech companies), or they may decide to take some vacation

- In order to get the benefits of the best case above, you need to take on massive interest rate risk, so the downside is potentially much larger than the upside (plus, in the downside case, you're poor for a much longer time)

Therefore, traders may choose not to short interest rates, even if they believe AI is imminent

Could you try to give an estimate as to how much money would be necessary to move the markets? I'm not particularly familiar with the Treasuries market, but I'm not convinced that a small number of traders or even a few billion dollars per year in "smart money" could significantly change it, at least not enough to send signals separate from surrounding noise about the views.

To try to group/summarize the discussion in the comments and offer some replies:

1. ‘Traders are not thinking about AGI, the inferential distance is too large’; or ‘a short can only profit if other people take the short position too’

(a) Anyone who thinks they have an edge in markets thinks they've noticed something which requires such a large inferential distance that no one else has seen it.

(b) Many financial market participants ARE thinking about these issues.

- Asset manager Cathie Wood has AGI timelines of 6-12 years and is betting the house on that (“AGI could accelerate growth in GDP to 30-50% per year”)

- Masayoshi Son raised $100 billion for Softbank’s Vision Fund on the basis that superintelligence will arrive by 20

... (read more)I trade global rates for a large hedge fund so I think i can give the inside view on how financial market participants think about this.

First, the essential claim is true - no one in rates markets talks about the theme of AI driving a massive increase in potential growth.

However, even if this did become accepted as a potential scenario it would be very unlikely to show up in government bond yields so using yields as evidence of the likelihood of the scenario is, imho, a mistake. I'll give a number of reasons.

- Rates markets don't price in events (even ones that are fully known) more than one or two years ahead of time (Y2K, contentious elections in Italy or France, etc). This is generally outside participants time horizons but also...

- A lot can happen in two years (much less ten years). Major terrorist attack, pandemic, nuclear war to name three possibilities all of which would fully torpedo any bet you would make on AI, no matter how certain you are of the outcome.

- The premise is not obviously true that higher growth leads to higher real yields. That is one heuristic among many when thinking about what real yields should do. It's important to think about the mechanism here

... (read more)Suppose you are one of the 0.1% of macro bonds traders familiar with Yudkowskian foom. You reason as follows: "Suppose that in the next 2 years, we get even more alarming news out of GPT-4 and successors. Suppose it's so incredibly alarming that 10% of macro traders notice, and then 10% of those hear about Yudkowskian foom scenarios. Putting myself into the shoes of one of those normie macro traders, I think I reason... that most actual normal people won't change their saving behavior any time soon, even if theoretically they should decrease their saving, and that's not likely to have macro effects. Still as a normie trader who's heard about Yudkowsky foomdoom, I think I reason that if Yudkowsky's right, we're all dead, and if Yudkowsky's not right, I'll get embarrassed about a wrong trade and fired. So this normie trader won't trade on Yudkowsky foomdoom premises. Therefore I don't think I can profit over the next two years by shorting a TIPS fund... even leaving aside concerning feelings about whether going hugely short LTPZ would have model risk about LTPZ's actual relation to real interest rates in these scenarios, or ... (read more)

Trying again:

OP seems to ambiguate between two ideas, one true idea, and one false idea.

The true idea is that if Omega tells you personally that the world will end in 2030 with probability 1, you personally should not bother saving for retirement. Call this the Personal Idea.

The false idea is that if you believe in foomdoom, you should go long real interest rates and expect a market profit. Call this the Market Idea.

Intuitively, at least if you're swayed by this essay, the idea in Market probably seems pretty close to the idea in Personal. If everybody started consuming for today and investing less, real interest rates would go up, right? So if you don't believe that Market is about as strong as Personal, what invalid reasoning step occurs within the gap between the true premise in Personal to the false conclusion in Market?

Is it invalid that if in 2025 everyone started believing that the world would end in 2030 with probability 1, real interest rates would rise in 2025? Honestly, I'm not even sure of that in real life. People are arguing clever-ideas like 'Shouldn't everyone take out big loans due later?' but maybe the lender doesn't want to len... (read more)

In appendix 3 the authors cite a paper which looks at more-or-less this precise thing:

It seems like government interest rates didn't change much? But I don't think I understand this graph.

I'm a bit confused by this comment. Is the claim that you can't profit from taking out a loan that you have to pay back in 2040? The fact that you get money now and have to pay it back at a time when hypothetically money no longer matters seems like profit to me. If Omega whispers the truth into my ear that in 2040 there will be foom, then that's guaranteed profit.

Nobody will give you an unsecured loan to fund consumption or donations with most of the money not due for 15+ years; most people in our society who would borrow on such terms would default. (You can get close with some types of student loan, so if there's education that you'd experience as intrinsically-valued consumption or be able to rapidly apply to philanthropic ends then this post suggests you should perhaps be more willing to borrow to fund it than you would be otherwise, but your personal upside there is pretty limited.)

The reason sophisticated entities like e.g. hedge funds hold bonds isn't so they can collect a cash flow 10 years from now. It's because they think bond prices will go up tomorrow, or next year.

The big entities that hold bonds for the future cash flows are e.g. pension funds. It would be very surprising and (I think) borderline illegal if the pension funds ever started reasoning, "I guess I don't need to worry about cash flows after 2045, since the world will probably end before then. So I'll just hold shorter-term assets."

I think this adds up to, no big investors can directly profit from the final outcome here. Though as everyone seems to agree, anyone could profit by being short bonds (or underweight bonds) while the market started to price in substantial probability of AGI.

Beyond just taking vacation days, if you're a bond trader who believes in a very high chance of xrisk in the next five years it

probablymight make sense to quit your job and fund your consumption out of your retirement savings. At which point you aren't a bond trader anymore and your beliefs no longer have much impact on bond prices.People disagreeing, would you say why?

My guess for the pushback: 1 week before the end of the world, you think a sizable part of the population will notice and change their economic behavior drastically. I imagine this scenario contains a slow "attack" by AI that everyone sees coming?

(agree vote = yeah that is the pushback)

If the only scenario for AI were: exist at more or less normal levels of economic growth, then foom, I think Eliezer would be correct. However, I think a likely scenario is that there is accelerated growth, coincident with accelerated risk (via e.g. AI terrorism or wars), before foom. This cluster of outcomes may even be modal. In that case, interest rates would very likely rise and traders would be able to profit, before foom.

Put another way, we often place substantial weight on non-foom good and bad AI scenarios, even if foom is a risk. The market seems to be ruling out non-foom AI risk as well as non-foom AI growth before foom. Eliezer is correct that the market may not be ruling out the (IMO unlikely) scenario of "no-AI induced growth or risk prior to foom, then foom."

What do you make of the 'impatient philanthropy' argument? Do you think EAs should be borrowing to spend on AI safety?

Nice post, but my rough take is there is

I'm curating this post because I think it raises important points that I'd like more people to engage with, and because the discussion on it has been really interesting (124 comments right now). I also think it'd be very good to have more genuine critical engagement with the case for prioritizing work on AI existential risk.

However, the post seems wrong or at least heavily disputable in important ways, so I will also point out relevant considerations and comments. Please note that I'm not an expert; in some cases, I'm merely summarizing my understanding of what others have said.

This comment ended up being very long. Before it goes on, I want to direct attention to some other content arguing against the case that risk from AI is high or should be prioritized:

The overall claim that the post is making is the following (I think):

- Markets are a good way of finding an

... (read more)I spent about an hour today trying to convince a friend that works in private equity that OpenAI is undervalued at $30B. I pitched him on short AI timelines and transformative growth, and he didn’t disagree with those arguments directly. He mostly questioned whether OpenAI would reap the benefits of short timelines. A few of the points:

IMO these are boring economic arguments that don’t refute the core thesis of short timelines or AI risk. OpenAI is getting a similar evaluation to Grammarly, which also sells an LLM product, but with worse tech and better marketing. It’s being evaluated on short term revenue prospects more than considerations about TAI timelines.

Thanks for writing this! I think market data can be a valuable source of information about the probability of various AI scenarios--along with other approaches, like forecasting tournaments, since each has its own strengths and weaknesses. I think it’s a pity that relatively little has yet been written on extracting information about AI timelines from market data, and I’m glad that this post has brought the idea to people’s attention and demonstrated that it’s possible to make at least some progress.

That said, there is one broad limitation to this analysis that hasn’t gotten quite as much attention so far as I think it deserves. (Basil: yes, this is the thing we discussed last summer….) This is that low real, risk-free interest rates are compatible with the belief

1) that there will be no AI-driven growth explosion,

as you discuss--but also with some AI-growth-explosion-compatible beliefs investors might have, including

2) that future growth could well be very fast or very slow, and

3) that growth will be fast but marginal utility in consumption will nevertheless stay high, because AI will give us such mindblowing new things to spend on (my “new products” hobb... (read more)

For what it's worth, I suspect many readers do think there's some chance of stagnation (i.e. put 5% credence or more). Will MacAskill devotes an entire chapter to growth stagnation in What We Owe the Future. In fact he thinks it's the most likely of the four future trajectories discussed in the book, giving it 35% credence (see note 22 to chapter 2, p. 273-4).

The Samotsvety forecasters think this is too high, but each still puts at least 1% credence on the scenario and their aggregated forecast is 5%. Low, but suggesting it's worth considering.

I am confused. This is not a lot of return at 10 year timelines, and calling it "mouth-watering" seems a bit excessive. A cumulative return of 162% over 10 years is equivalent to around 10% annually, which is around as good as putting a money into a normal ETF over the last 20 years (which averaged around 8-10% over the last 20 years), and this is not considering that since I am short the market, in any world where I am wrong, I will likely lose a lot of money. If I take the downside into account, I end up with an annualized return of around 5-6% on this portfolio, which really doesn't seem great to me.

Taking the math here at face value, you are suggesting a trading strategy with a ~5-6% annualized return, which is maybe barely competetive with other investing strategies, and a lot less than the average return of most EA-adjacent investor who have been thinking about this stuff for the last few years... (read more)

Duration doesn't mean time to maturity. It's a measure of bond sensitivity to interest rates. Higher duration = more sensitivity. It's measured in years tho which is confusing. You can make your 162% in one year if the interest rates move as the authors say, which is pretty mouth-watering!

(edit: just to showcase the degree of difference, a bond with 40 years to maturity can have duration of just 10 years if the bond's coupon value is 10% & market rates were also 10% at the time of isssuance. This means the value of the bond will change less with rising rates. A 40-year bond with a 1% coupon, issued when market rates were also 1% will have duration of around 33 years, which in plain English just means that if interest rates go up a lot you get "FTX-linked tokens in November" returns. Bonds are tricky things and their pricing is weird is especially in ZIRP environments)

This post's thesis is that markets don't expect AGI in the next 30 years. I'll make a stronger claim: most people don't expect AGI in the next 30 years; it's a contrarian position. Anyone expecting AGI in that time is disagreeing with a very large swath of humanity.

(It's a stronger claim because "most people don't expect AGI" implies "markets don't expect AGI", but the reverse is not true. (Not literally so -- you can construct scenarios like "only investors expect AGI while others don't" where most people don't expect AGI but the market does expect AGI -- but these seem like edge cases that clearly don't apply to reality.))

Personally I feel okay disagreeing with the rest of humanity on this, because (a) the arguments seem solid to me, while the counterarguments don't, and (b) the AGI community has put in much more serial thought into the question than the rest of humanity.

If you already knew that belief in AGI soon was a very contrarian position (including amongst the most wealthy, smart, and influential people), I don't think you should update at all on the fact that the market doesn't expect AGI.

If you didn't know that, consider this your wake up call to reflect on the fact that... (read more)

I'm not sure that's true. Markets often price things that only a minority of people know or care about. See the lithium example in the original post. That was a case where "most people didn't know lithium was used in the H-bomb" didn't imply that "markets didn't know lithium was used in the H-bomb"

If investors with $1T thought AGI soon, and therefore tried to buy up a portfolio of semiconductor, cloud, and AI companies (a much more profitable and capital-efficient strategy than betting on real interest rates) they could only a buy a small fraction of those industries at current prices. There is a larger pool of investors who would sell at much higher than current prices, balancing that minority.

Yes, it's weighted by capital and views on asset prices, but still a small portion of the relevant capital trying to trade (with risk and years in advance) on a thesis impacting many trillions of dollars of market cap aren't enough to drastically change asset prices against the counter trades of other investors.

There is almost no discussion of AGI prospects by financial analysts, consultants, etc (generally if they mention it they just say they're not going to consider it). E.g. they don't report probabilities it would happen or make any estimates of the profits it would produce.

Rohin is right that AGI by the 2030s is a contrarian view, and that there's likely less than $1T of investor capital that buys that view and selects investments based on it.

I, like many EAs, made a... (read more)

- But the stocks are the more profitable and capital-efficient investment, so that's where you see effects first on market prices (if much at all) for a given number of traders buying the investment thesis. That's the main investment on this basis I see short timelines believers making (including me), and has in fact yielded a lot of excess returns since EAs started to identify it in the 2010s.

- I don't think anyone here is arguing against the no-trade theorem, and that's not an argument that prices will never be swayed by anything, but that you can have a sizable amount of money invested on the AGI thesis before it sways prices. Yes, price changes don't need to be driven by volume if no one wants to trade against. But plenty of traders not buying AGI would trade against AGI-driven valuations, e.g. against the high P/E ratios that would ensue. Rohin is saying not that the majority of investment capital that doesn't buy AGI will sit on the sidelines but will trade against the AGI-driven bet, e.g. by selling assets at elevated P/E ratios. At the moment there is enough $ trading against AGI bets that market prices are not in line with the AGI bet valuations. I reco

... (read more)I'll just pop back in here briefly to say that (1) I have learned a lot from your writing over the years, (2) I have to say I still cannot see how I misinterpreted your comment, and (3) I genuinely appreciate your engagement with the post, even if I think your summary misses the contribution in a fundamentally important way (as I tried to elaborate elsewhere in the thread).

This is one way of looking at the data (with my overlapping data claim already noted).

Here is another (much longer) way of looking at the data.

Here is 800 years of history courtesy of the BoE

Eyeballing that, I'd say the relationship is strongly negative...

I would guess some combination of:

I don't really have a strong opinion on any of these - macro is really hard and really uncertain. To quote a friend of mine:

Borrowing and consuming because AGI is coming seems an incredibly risky proposition.

I've been discussing this concept for some time now, so I'm glad to see some people take a more formal stab at it. However, I must say that I'm overall disappointed with this post. I'll just lay out a few summary points, and if people are actually still reading this deep into the comments and want to hear more thoughts, I can oblige later:

- With the *slight* exception of the "you could be earning alpha" section, it does not really get deep into the causal mechanisms for why you should expect markets to be efficient.