Alt Title: A Case for Supporting the Yes On IP28 Campaign

It is safe to say, that from the middle of January, 1877, until the following October, the most prominent theme of public discussion was this question of suffrage for women. Miners discussed it around their camp-fires, and “freighters” on their long slow journeys over the mountain trails argued pro and con, whether they should “let” women have the ballot.

History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 3

Introduction

Denigrated as “bawling, ranting women, bristling for their rights,” the all-male electorate voted two-to-one rejecting the 1877 ballot measure that would have extended suffrage to the women of Colorado. This was the fourth women’s suffrage ballot initiative to be defeated at the polls, after previous campaigns in Michigan (1874), Nebraska (1871), and Kansas (1867) received similarly unfavorable results—securing only 23%, 22%, and 31% of the vote, respectively. Nevertheless, they persisted. Between 1867 and 1920, fifty-four measures to grant women’s suffrage were on the ballot in states across the country, only fifteen of which were approved by voters prior to the ratification of the 19th amendment. In some states, such as Oregon, it took six attempts before finally receiving the majority of votes cast.

Despite the many “defeats,” the suffragists felt encouraged by what they saw as progress for the movement:

On November 3 the amendment received 39,605 ayes and 51,519 noes, lost by nearly 12,000. For the fifth time the men of South Dakota had denied women the right of representation. The suffrage leaders were not in the least daunted or discouraged.

With all the obstacles which the dominant party could throw in our way, without organization, without money, without political rewards to offer, without any of the means by which elections are usually carried, we gained one-third of all the votes cast!

The amendment was defeated, receiving 35,290 ayes, 57,709 noes, but the workers felt that gains had been made and were more determined than ever not to cease their efforts.

The taunts and jeers of the opposition; all this is passed, but the great principle of human rights which we advocated remains, commending itself more and more to the favor of all good men, confirmed by every year’s experience, and destined at no distant day to find expression in law.

But [in] Kansas, there was no chance of victory…but the seed sown has silently taken root and sprung up everywhere. Or rather, the truths then spoken, and the arguments presented, sinking into the minds and hearts of the men and women who heard them, have been like leaven, slowly but surely operating until it seems to many that nearly the whole public sentiment of Kansas is therewith leavened.

As evident from the quotes above as well as this article’s epigraph—all excerpts from the six-volume History of Woman Suffrage produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Ida Husted Harper—the organizers of the suffrage movement felt that forcing the vote on extending the franchise stimulated widespread public discourse and shifted public sentiment to the point that Congress became “compelled” to submit a federal suffrage amendment. It is my conviction that a similar strategy can be used to codify the inviolable rights of animals.

According to political philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, “the idea that animals possess inviolable rights is a very distinctive view which goes beyond what is normally understood by the term animal rights,” and in their book Zoopolis they articulate the following distinction:

In everyday parlance, anyone who argues for greater limits on the use of animals is said to be a defender of animal rights. Thus, someone who advocates that pigs being raised for slaughter should have larger stalls, so as to improve the quality of their short lives, is described as a believer in animal rights. And indeed we can say that such a person believes that animals have a ‘right to humane treatment’. Someone defending a more robust view might argue that humans should not eat animals since we have lots of nutritious alternatives, but that medical experiments on animals are permissible if this is the only way to advance crucial medical knowledge, or that culling wild animals is permissible if this is the only way to save key habitats. We can say that such a person believes animals have a ‘right not to be sacrificed by humans unless an important human or ecological interest is at stake’. These views, whether they endorse a weaker or more robust conception of, are crucially different from the idea that animals have inviolable rights.

This differentiation is not intended to divide or disparage activities that may fall under the broader category of animal rights, but rather to help clarify what I am advocating for. In addition to my view that the suffragists have demonstrated the incredible potential of ballot initiatives for social change, it is also my position that a nationwide campaign forcing the public to vote on protecting animals’ inviolable rights would create the cultural evolution necessary to prevent incremental changes from being undone and to achieve what left social movements refer to as “non-reformist reforms.” In just the same way that the world began considering whether to “let” women have the right to vote, I want the world to earnestly consider whether to “let” animals have the right to a life free from slaughter, hunting, experimentation, confinement, forced breeding, and other forms of exploitation. To make this a reality, I believe we must commence the conversation, build a political bloc, and advocate with authenticity.

Commence the Conversation

Considerable debate is being had about the pros and cons of factory farming, more research than ever before is being published on vegan & plant-based diets, and the animal advocacy movement’s budget continues to grow, but it is readily apparent that the general public is not widely conversing about animals' inviolable rights. Retail workers aren’t discussing how they'd vote on a universal hunting ban, and truck drivers aren’t deliberating over their CB radios about whether they support eliminating the practice of animal slaughter. Revisiting the book Zoopolis, I believe Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka allude to the kinds of campaigns that can commence such conversations.

Campaigns ranging from the very first nineteenth-century anti-cruelty laws to the 2008 Proposition 2 may help or hinder at the margins, but they do not challenge—indeed, do not even address—the social, legal, and political underpinnings of [animal exploitation]. (… ) Accepting that animals are selves or persons will have many implications, the clearest of which is to recognize a range of universal negative rights—the right not to be tortured, experimented on, owned, enslaved, imprisoned, or killed. This would entail the prohibition of current practices of farming, hunting, the commercial pet industry, zoo-keeping, animal experimentation, and many others.

Since the United States is unique in that many localities allow citizens to circulate a petition to initiate a binding public vote on changes to city, county, and state law—bypassing their local and state legislatures—animal advocates in the U.S. have an opportunity to force a vote (or, as we recall from the case of women’s suffrage, fifty-four votes) on issues that might otherwise be left out of political conversations or that challenge the status quo in ways most elected officials would shy away from. This is the rationale behind Initiative Petition 28 (IP28), an Oregon ballot initiative for the 2026 election that proposes to ban the injuring, killing, and forced breeding of animals (including for slaughter, hunting, and experimentation).

In every state and country with animal cruelty laws on the books, you will find that such laws are intentionally written to avoid criminalizing activities that exploit animals in ways society has deemed acceptable. The exemptions might vary in their appearance, but their consequences remain the same. IP28 works by removing these exemptions from Oregon’s animal cruelty laws, thereby extending the same protections that keep our companion animals safe to those animals currently on farms, in labs, and in the wild.

Strictly speaking, Oregon’s definition of animal abuse would remain the same if IP28 were to pass—the radical shift concerns the circumstances under which this definition applies. Rather than exclusively covering the animals we live with in our homes, every mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, and fish would be protected from being “intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly” injured or killed. Forced masturbation and insemination would also be included in the definition of animal sexual assault, which currently criminalizes forced contact with an animal’s genitals only if it results in the gratification of the human’s sexual desire.

If the Yes On IP28 campaign is successful in qualifying for the ballot in 2026—and at time of publication the campaign has collected 40,000 signatures and has until July of 2026 to hand in enough to meet the 117,173 signature requirement—over three million registered voters will be asked for the first time in history whether they want to recognize these universal negative rights for animals. By focusing our campaign on these inviolable rights, we help shift the narrative around animal advocacy towards a civic/political frame, which has been recommended by both Animal Think Tank and Pax Fauna. It has also been recommended by Faunalytics to make greater use of news articles in animal advocacy, something that ballot initiative campaigns quite often bring about.

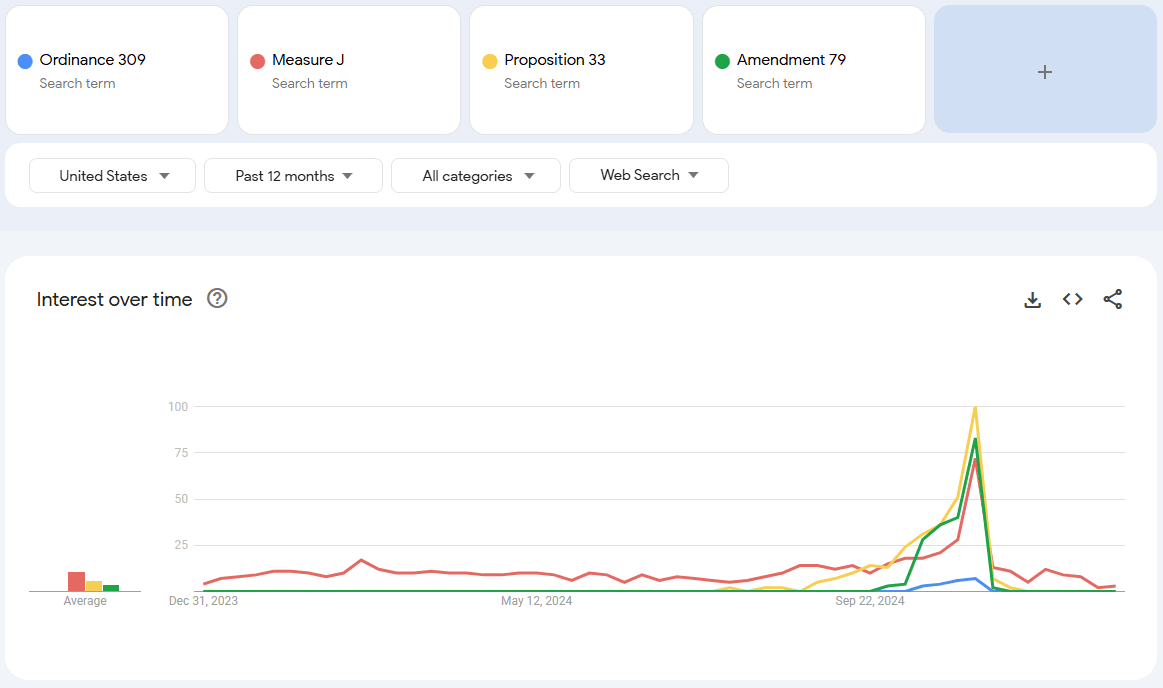

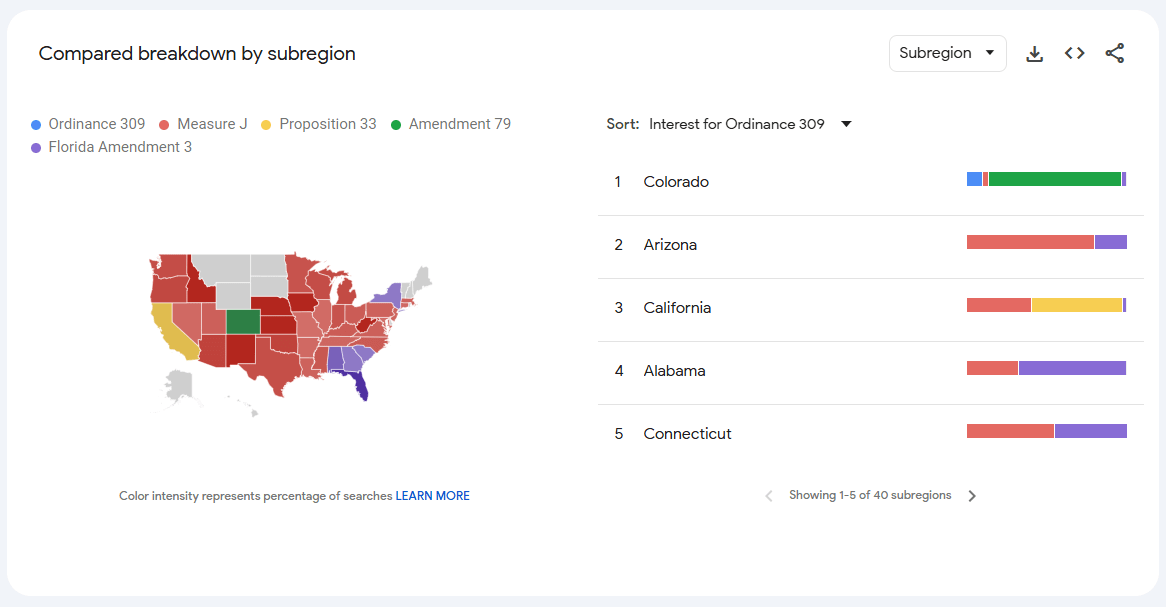

According to the campaigns from the recent 2024 ballot initiatives to ban factory farming in Sonoma County (Measure J) and to ban slaughterhouses in the City of Denver (Ordinance 309), the former generated over 130 press hits and the latter resulted in at least 80 news stories and 17 op-eds. One of the take-aways from both campaigns is that ballot initiatives can be a strong stimulus for public discourse, reiterating the lessons already learned from the history of women’s suffrage. It is also my impression, however, that despite fewer Americans closely following both local and national news in similar numbers, statewide initiatives have the tendency to receive greater coverage overall (as an example, the Associate Press, CNN, NBC, Fox News, and NPR all reported exclusively on statewide ballot measures in their 2024 election trackers). While it is certainly still possible for local campaigns to generate as much or even more interest as some statewide campaigns (see figures 1-3)—and I believe local initiatives are valuable to continue regardless of their relative news coverage potential, particularly when done as a means to build capacity as a movement—I also maintain that current conditions make state level initiatives particularly conducive for prompting national discussion.

The CA and CO statewide initiatives saw more interest from within their own state compared to Measure J and Ordinance 309, however, in states where an in-state statewide measure was not being compared, many states took more interest in Measure J than in either the CA, CO, or FL initiatives. I believe this is due to the impact Measure J would have on those who earn income from the breeding and slaughter of farmed animals, and I think supports the claim that IP28 has a high potential for prompting public interest both in and out of Oregon given that it is both a statewide measure and that it substantially impacts agricultural practices that currently rely on violence against animals.

Statewide initiatives similar to IP28 also contain one additional narrative advantage. Because most animal cruelty laws are codified in state rather than local statutes, it is possible to craft legislation that protects an animal’s inviolable right not to be slaughtered, hunted, experimented on, or sexually violated simply by expanding who our current cruelty protections apply to (i.e. rather than creating entirely new laws or protections, current legal protections can simply be amended). Such legislation necessarily points out the human-created distinction between companion animals and the animals we exploit for food, clothing, and entertainment, raising this cognitive dissonance in ways similar to Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat.

While IP28 works by amending state cruelty laws, this strategy may not always be available. In North Dakota, for instance, there is a constitutional amendment protecting the “right of farmers and ranchers to employ agricultural technology, modern livestock production, and ranching practices,” which would preempt a statutory ban on slaughter. Nevertheless, all this would require is a ballot initiative that protects animals’ inviolable rights through a constitutional amendment rather than changes to state statutes—which may require a greater number of signatures but is otherwise largely an identical process. Missouri is the only other state with such a constitutional amendment, as most of these so-called “right-to-farm laws” are statutory laws that generally aim only to protect farmers from property disputes and litigation—and, since they are statutory, they can be superseded by the passage of newer statutes which take precedence over any conflicting provisions in older laws.

Just as the forms of our animal cruelty laws may vary, so too can the forms of our legislation to protect animals’ inviolable rights. What’s more important with respect to making this movement the most prominent theme of public discussion is that our message is unified and that together we combine our efforts to further this common purpose.

Build a Bloc

From 1869 to 1889, two national organizations led the fight for women’s suffrage: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). While the former gave primacy to achieving enfranchisement at the federal level, the latter concentrated their efforts on extending the right to vote at the state level. Initially in the early 1870s, the NWSA’s strategy was to achieve suffrage through the courts by arguing that the constitution implicitly enfranchised women already. This is why Susan B. Anthony was arrested for attempting to vote—so that they would have standing to file the lawsuit that eventually worked its way to a U.S. federal court. Susan B. Anthony was ultimately found guilty in United States v Susan B. Anthony, and after this ruling the NWSA shifted their efforts towards a constitutional amendment that would explicitly grant women the right to vote. Meanwhile, the AWSA supported the eight statewide initiatives that took place in Nebraska (1871 & 1882), Michigan (1874), Colorado (1877), Oregon (1884), Rhode Island (1887), Washington (1889), and Wyoming (1889)—with Wyoming becoming the first state to pass such a measure.

In 1888, the NWSA organized the founding meeting of the International Council of Women, where delegates representing women’s organizations from nine countries came together so as to make themselves heard at the international level. Two years later in 1890, the NWSA and AWSA merged to form the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Growing from an initial 7,000 dues-paying members to a membership of about two million, the NAWSA was considered the bulwark of the movement and continued to advocate for statewide ballot measures—which suffragists Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler described as having “spun the main thread of suffrage activity.” While there continued to be internal tensions over choices of strategy, ultimately the movement saw fifteen states grant women the right to vote by 1918 and in 1920 the 19th Amendment was ratified.

My reason for laying out this brief history of suffrage organizations is because it stimulates in me a vision for what I believe could be a theoretical (and effective) trajectory—at least in broad strokes—for a confederated movement dedicated to protecting the inviolable rights of animals. I’d like to share this vision with the clarification that it consists merely of “ideas and suggestions rather than formal designs.” While I may make allusions (or even explicit references) to animal rights organizations and their potential future directions, I have no attachment to this particular utopic narrative. Instead, to paraphrase Kristen Ghodsee from her interview for Current Affairs, envisioning one hypothetical course of action might orient ourselves in a direction that helps us make forward progress.

Twenty-four states in the U.S. allow for either citizen-initiated changes to state statute or state constitutional amendments. As already mentioned, 2026 may be the first year a statewide vote is held on protecting the previously enumerated negative rights of animals. Four years passed between the first two statewide votes for suffrage, will the same be true for animal rights? If Oregon is the first state, which could be the next? Given the existence of Pro-Animal Future and Compassionate Bay, Colorado and California might be top contenders—although Arizona and Florida may prove as formidable contenders given they each allow for two years of signature collection (similar to Oregon) and their warmer winters and longer days are ideal for petitioning. How many state campaigns will begin before the formation of an organization similar to the AWSA becomes beneficial for the coordination of activities and resources?

Meanwhile, as organizations like the Nonhuman Rights Project and Direct Action Everywhere work to fight for legal rights through the courts—arguing that some laws already implicitly recognize animals as legal persons or that new legal precedent could open the door to such a view—will there be an eventual shift towards advocating for explicit recognition in a manner similar to the direction of the NWSA? Happy the elephant was ultimately ruled as not a person, and so far no court in the United States has recognized personhood for animals. Maybe it’s time we follow in the footsteps of Tierschutzpartei, an animal rights political party in Germany, in their proposal to add to Germany’s constitution an article that states:

As our fellow creatures, animals have the right to life, the right to physical integrity and the right to freedom for their own sake. (...) These rights may only be curtailed by humans in cases of self-defense or when their observance is not possible...However, animals must never be deliberately exploited or killed in this process [of satisfying essential human needs].

The International Council of Women marked the 40th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, which is said to have launched the women’s suffrage movement in the United States. Will there be a council to mark 40 years on from the first statewide vote for animals’ inviolable rights? Delegates from the eighteen animal rights parties throughout the world could be in attendance to elevate the call for animal protection. Perhaps, two years later, an organization will form that merges Rose’s Law with The Declaration of Animal Rights into a united call for a constitutional amendment—all the while increasing the number of states that have protected the rights of animals until there comes a day when that number, to use the words of Susan B. Anthony, “will automatically and resistlessly act on the Congress of the United States to compel the submission of a federal amendment.”

Regardless of whether any of the above events end up as part of the ultimate path towards achieving inviolable rights for animals, I believe building an expressly political coalition is part of the way forward. And when we see ourselves as a continuation of history’s progressive social movements, we may become empowered to advocate for the world we want.

Advocate with Authenticity

In my attempt to return once again to the suffrage movement for inspiration, I began searching through the History of Woman Suffrage for any discussion of authenticity. I came across two strands of thought that prompted me to delve deeper into why I believe it is effective to be authentic. While the word authentic itself was largely used throughout the text to refer to the origin of documents or speech (i.e. as being original or genuine), it appeared that the word conviction was more commonly used in the kinds of contexts I was seeking. The first strand of thought is captured by two quotes, one from Ernestine Louise Rose—who has been called the “first Jewish feminist” and is believed to have coined the phrase “women’s rights are human rights”—and the other from Susan B. Anthony.

During the eighth National Women’s Rights Convention, held in New York City on May 13-14, 1858, Ernestine Rose shared the following: “If we are loyal to our highest convictions, we need not care how far it may lead. For truth, like water, will find its own level.” Many years later as part of a remembrance ceremony for Ellen Battelle Dietrick, the founding vice-president of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association (one of the many state-level suffrage associations), Susan B. Anthony observed that “there are very few human beings who have the courage to utter to the fullest their honest convictions—Mrs. Dietrick was one of these few. She would follow truth wherever it led, and she would follow no other leader. Like Lucretia Mott, she took ‘truth for authority, not authority for truth.’”

It is my impression that both of these quotes point towards a shared belief that being authentic, or holding to one’s convictions, is a positive attribute that would benefit their social change work (particularly as leaders in the movement). While I agree that the consequences of authenticity help us in achieving social justice, I am concerned by the implied equivalence in these quotes between one’s convictions and truth—for perhaps similar reasons as to why Nietzsche has claimed that “convictions are more dangerous foes of truth than lies.” I believe Ernestine Rose and Susan B. Anthony may have held the view that the reason authenticity is effective is because their convictions were true. My personal view is more similar to that expressed by Angelina Emily Grimké, who—along with her sister Sarah Moore Grimké—were considered the only notable examples of white Southern women abolitionists.

A conversation between Angelina and Sarah was recounted in the History of Woman Suffrage, during which Angelina was discussing with Sarah why she was planning to accept an invitation from the American Anti-Slavery Society to help them do work in New York City despite her being, in Sarah’s words, “self-distrustful, easily embarrassed” and having “a morbid shrinking from whatever would make [her] conspicuous." Angelina replied to her sister’s concerns by stating that her mind was made up, for it would be “very unpleasant…to be disowned, but misery to be self-disowned.” Angelina, it seems, made the same observation that Hannah Arendt did over one-hundred years later: that it is “better to be at odds with the whole world than be at odds with the only one you are forced to live together with when you have left company behind.”

Instead of a claim to truth or righteousness, this view suggests that the reason it is effective to be authentic is because it helps to meet a fundamental human need for authenticity—or to use the language of Manfred Max-Neef, our need for identity. According to his research, we meet what he describes as our need for identity through having a personal sense of belonging, consistency, and values, or by committing oneself, by knowing oneself, and by confronting oneself. To quote Max-Neef himself, “the realization of needs becomes, instead of a goal, the motor of development itself.” Notwithstanding the fact that in this context he was discussing human and economic development, I believe the same is true for the development of social movements. Rather than the realization of our needs being the goal of our activism, meeting our needs becomes the thrust behind our activism.

Even as I give primacy to authenticity as a means for animating ourselves, I also hold the view that uttering to the fullest our honest convictions helps, rather than hinders, the likelihood that others will receive our messages in ways that further social progress—particularly given the gradual shift towards a greater importance of authenticity in the public sphere (emblematized by authentic becoming Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2023). While there are concerns about how this increased desire for authenticity appears to be incentivising what researchers describe as politically incorrect speech, and what one associate professor of organization theory describes as the breaking of democratic norms, I disagree with the latter when he concludes in his article that the solution is to “reduce the demand for authenticity.” I prefer instead the suggestion made by the aforementioned researchers, who wrote that an alternative strategy to effectively demonstrate authenticity would be to “directly reveal [our] true selves to the public,” which is done when our actions “do not seem strategic but rather driven by [our] true convictions.”

To avoid compromising my convictions in an attempt to be strategic, I advocate for protecting the inviolable rights of animals. This is why IP28 seeks to ban the intentional injury, killing, and forced breeding of animals in Oregon including for slaughter, hunting, and experimentation. Although I am deeply concerned with being responsive to the needs of others, which we hope to express clearly in all of our campaign communications and have put much effort into making clear on our campaign website’s FAQ page, it is my intention not to diminish my position out of concern for the real or perceived evaluations of others. As already mentioned, I fear doing so would delay—or outright prevent—rather than hasten the time it takes to bring about freedom for animals. If we want the world to talk about animals’ inviolable rights, I believe we must embrace authenticity, unite our voices together, and ask for the world we want.

Conclusion

When the American Woman Suffrage Association was founded in 1869, any person could become a member by paying the sum of $1 annually. In today’s dollars accounting for inflation, that would be roughly $24. If you would like to support the IP28 campaign, you can become a one-time or monthly donor through our website at yesonip28.org/donate, where you can also find our full-length video titled “Why Donate to the Yes On IP28 Campaign.”

I’d very much enjoy continuing the conversation in the comments below or privately (you can email me at david@yesonip28.org). I will also be attending the upcoming EA Global: Bay Area 2025, and would be happy to meet during the conference to talk further about any of the ideas presented in this post.

This article was inspired by a previous EA Forum post from @Lewis Bollard, titled How can we get the world to talk about factory farming?

"You cannot awaken someone if you do not approach them as if they were not sleeping." ~Revolution and Other Writings: A Political Reader, by Gustav Landauer

Executive summary: Ballot initiatives to establish inviolable rights for animals, similar to historical women's suffrage campaigns, can effectively stimulate public discourse and create lasting social change, as demonstrated by the current IP28 campaign in Oregon.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.