TL;DR: ARMoR, or the Alliance for Reducing Microbial Resistance, is a Charity Entrepreneurship incubated advocacy organisation combating the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). We aim to help drive policy change to secure a sustainable pipeline of new antimicrobials while also ensuring equitable access to these drugs across the globe. You can find our website here.

Disclaimers:

- This post will not dive deep into the antimicrobial resistance as a cause area, but you can read more about why it’s important here. As a general rule, we will not cover many of the more technical aspects of this intervention in this post, but if you have questions feel free to contact us directly.

- Throughout this post we will mainly be discussing information and statistics related to antibiotic resistance as this is much more widely studied than other forms of antimicrobial resistance, however, the broad themes largely holds true for other forms of resistant microbes such as fungi and parasites. We use antimicrobial or antibiotic deliberately when citing facts and figures

The Problem

What is antimicrobial resistance?

Antimicrobials are medicines that kill or prevent the spread of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Because of antimicrobials, many of us are no longer at risk from dangerous infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, sepsis, and meningitis. Over time, as we use these drugs to combat infections, the microorganisms we are targeting evolve and develop resistance to our treatments, rendering them ineffective, a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

At least 1.27 million deaths and 47 million DALYs are already directly attributed to bacterial AMR each year, surpassing the toll of both malaria and HIV. This number is rising at an alarming rate and some studies have estimated that, without serious intervention, antimicrobial resistance could overtake cancer as a leading cause of death by 2050 with 10+ million fatalities each year.

Although the majority of the AMR burden (over 90%) falls on LMICs, this is a global issue with over 2.8 million infections, 35,000 deaths and 55 billion dollars in economic losses each year in the US alone. Furthermore, because functioning antimicrobials are an essential part of modern medicine, losing them will mean losing our ability to perform surgery and chemotherapy and manage many chronic conditions in a way which has an acceptable level of risk.

What makes this a difficult problem to solve?

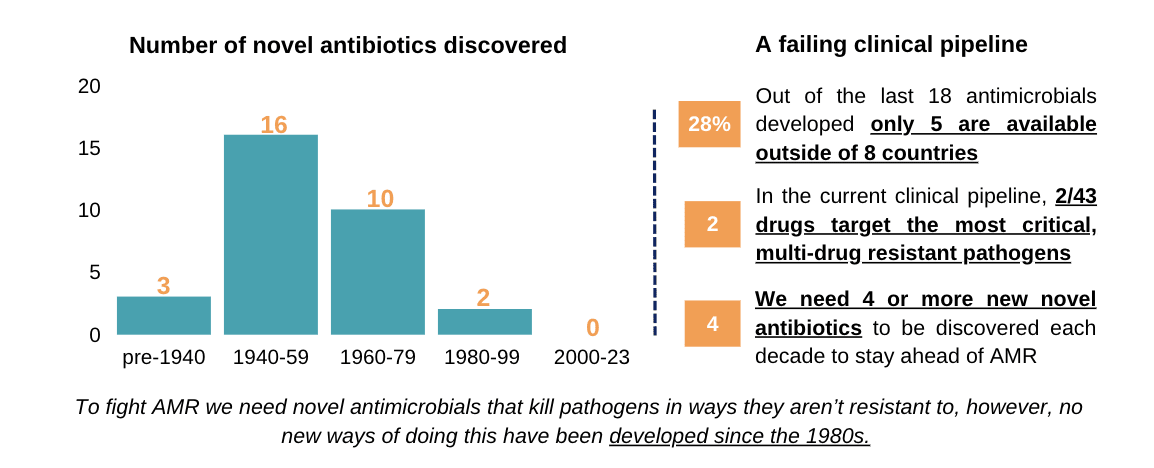

To combat the rising tide of AMR, a strong pipeline of novel antimicrobials coming to market is essential (alongside good stewardship and equitable access). Unfortunately, this is far from the case, as demonstrated by the following statistics:

- As of 2021, there were only 43 antibiotic drug candidates in clinical development.

- Only 2 of these target the most critical, “gram-negative” multi-drug resistant pathogens (for comparison there were >1,300 oncology medicines in clinical development at the same point)

- In the last 40 years we haven’t had any truly “novel” antibiotics be discovered, developed and commercialised

- A novel drug is defined based on its “mechanism of action” (i.e. the way the antimicrobials interact with the microbe to kill them or limit their growth) or it’s core structural motif.

- This means that recently developed antibiotics are closely related “analogues” of existing drugs and therefore are susceptible to the same resistance patterns or see resistance arise faster than with truly novel drugs

- Currently it is estimated we need 10 - 15 new antibiotics per decade to stay ahead of AMR, with 4 or more of these needing to be novel.

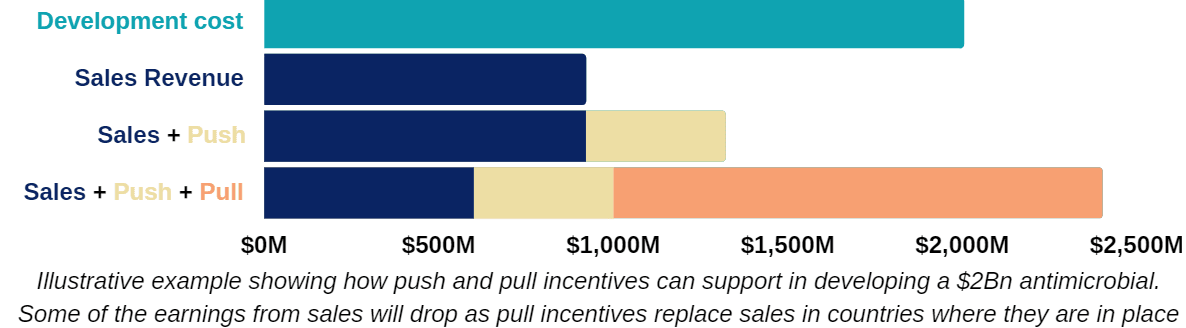

The good news is that the development of novel antimicrobials appears to be possible from a scientific standpoint. The problem is that the cost of developing new antimicrobials is very high ($1-5 billion per drug), while limited sales (median $25-75M/year for a 8-12 year market exclusivity period) make development unsustainable. Governments have attempted to resolve this issue through “push incentives”, such as grants and subsidies to support R&D, which have gone some way towards aiding early phase development, but failed to support more expensive, late stage development and commercialisation.

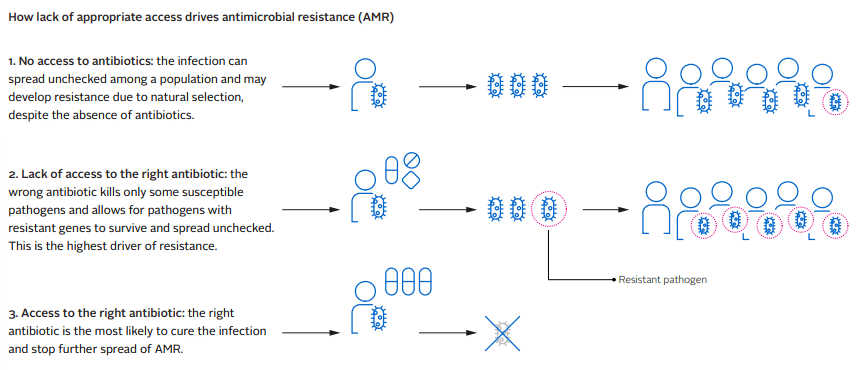

Even when new antimicrobials are successfully developed, they are often not sold widely due to insufficient profitability, even in HICs. Of the last 18 antimicrobials to come to market, only the US, UK, Sweden and France have access to more than seven of them. Japan has access to five and Canada just two. Given this, it is perhaps unsurprising that new life-saving antibiotics are rarely available in LMICs, which have the highest AMR burden. This lack of access is problematic for obvious reasons, but can also further the speed at which antimicrobial resistance develops. Because doctors don’t have access to the diagnostic tools and treatments needed, they often resort to prescribing less effective antimicrobials that are available to them. This gives pathogens an opportunity to develop resistance as explained in the following diagram.

Our Solution

Pull Incentives

One promising solution for restarting the antimicrobial pipeline and ensuring equitable access to effective drugs is for governments to adopt “pull incentives”. These incentives reward pharmaceutical companies a guaranteed revenue for bringing new, high-value antimicrobials to market, therefore encouraging development and, ultimately, reducing the burden of AMR. Pull incentives can be either financial or regulatory. Some examples include:

- Financial:

- Regular yearly payments (a “subscription” model or “Netflix” payment model) such as the model the UK is currently piloting

- One off payments upon approval, or “market entry rewards”

- Regulatory:

- Fast track regulatory reviews

- “Transferable exclusivity vouchers” which can be used to extend the market exclusivity of any of the companies products or sold to another company

Of the options that have been widely discussed for pull incentives, we favour subscription model as the most promising option to:

- Improve the antimicrobial ecosystem through creating a sustainable market

- Encourage innovation by rewarding the highest value antimicrobials more so than less valuable drugs

- Ensure appropriate usage (therefore reducing resistance to these new drugs) through fully decoupling sales volumes from revenue and ensuring supply as part of a contract for ongoing payments.

Recent analysis by the Centre for Global Development has shown these types of incentives have the potential to save millions of lives and give G7 and EU governments a return on investment of 23:1 within their own countries, which rises to 125:1 when taken globally.

Many of the world’s largest economies have already given vocal support for pull-incentives, including the G7 health and finance ministers and the G20 health ministers. However, only the UK and Sweden have taken action to implement pilots, with the US (The PASTEUR Act - potentially worth up to $6Bn over 10 years), EU (Transferable Exclusivity Vouchers scheme, 10 vouchers over 15 years), Canada (Subscription model, similar to the UK), and Japan (Subscription model, similar to the UK, but likely much smaller) considering passing their own policies.

From our initial analysis of the space, it seems that this lack of action is due to antimicrobial resistance not being a national priority, uncertainty around how to adopt pull-incentives, and countries being hesitant to be early adopters. We believe that this combination of widespread support but lack of concrete action presents a strong opportunity for impact.

Although there are already several actors working to combat AMR, few are focused on translating research into policy and supporting pull-incentives as a solution. Even fewer are working to ensure LMIC access (see below). After speaking to several experts and actors in the space, it seems clear that there is value to be gained from an organisation conducting targeted, evidence-based advocacy work.

LMIC access

Pull incentives alone don’t guarantee new antimicrobials will become available in areas with high-unmet need, which are usually LMICs. However, they can be used to support improvements to access through including appropriate “access clauses” in the contracts that are awarded to successful developers. Some examples of what these could be include:

- Pull incentives are awarded conditional on innovators supplying new antimicrobials to LMICs at an affordable price (there is a clause in the US PASTEUR act relating to this, although it isn’t particularly strong)

- Innovators agree to licence the drug to third parties who supply LMIC markets that they don’t intend to enter

- This could be supported though a pooled procurement system or global access hub (similar to how Covax operated for Covid-19 vaccines)

- LMICs are given the opportunity to participate in pull incentives themselves (potentially on a GDP matched basis to the commitments of HICs)

We believe that the LMIC access is a particularly neglected component of efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance.

Our Plan

ARMoR aims to play a pivotal role in the adoption and implementation of pull incentive policies across G20 and EU countries. To achieve this we plan to work at a country level, with an initial geographical assessment suggesting that Germany, the Netherlands, Australia, Ireland, France, and India (roughly in that order) would be promising countries to work in. Our work will involve developing evidence based policy interventions and working with the relevant government stakeholders to get these in place.

In addition to this bottom-up, country-level approach, once the organisation is more established, we intend to pursue opportunities for top-down international harmonisation. This could include activities such as supporting the EU in standardising approaches for member states or improving coordination G7 countries pull incentive schemes.

For more specific information about our strategy, please contact us directly on hello@armoramr.org.

How you can get involved

Tackling antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a massive problem, and one that we cannot solve on our own. In this section, we have compiled a selection of resources for you to learn more about the problem of AMR as well as several opportunities for you to make an impact yourself. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions.

- Connect us with relevant actors. Do you know (or are you) someone who can help advise or work with us? We are looking for people with experience in the following areas:

- EU and G7 policy development and advocacy (especially in Germany, the Netherlands, or another one of our target countries)

- Pharmaceutical industry and drug development

- Antimicrobial resistance (technical research, NGO, etc.)

- Launching policy charities/organisations

- Academics working in biosecurity, AMR, policy or economics

- Other EA orgs working in the biosecurity and policy space

- Volunteer to take on a small-scale project. We have plenty of opportunities for volunteers to get involved and work on high-impact projects (even if it’s not necessarily working for us). Here are some examples:

- Review our research reports and policy briefs (especially if you have relevant background experience)

- Conduct a stakeholder analysis for potential target countries

- Create infographics explaining different aspects of the AMR landscape

- Help us translate key documents and navigate target countries

- Learn more about the AMR space. Here are a few resources to get you started:

- The Case for a Subscription Model to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance

- Who will pay for new antibiotics?

- A New Grand Bargain to Improve the Antimicrobial Market for Human Health (the entire report is long but the introduction is good on its own)

- Delinking Investment in Antibiotic Research and Development from Sales Revenues: The Challenges of Transforming a Promising Idea into Reality

- Check out our website and subscribe to our newsletter for updates

If you have any other ideas or questions about how you can get involved, don’t hesitate to reach out to us. You can do this by sending an email to hello@armoramr.org.

Thanks for sharing!

Could you give a sense of what would happen in case no more "truly novel" antibiotics were discovered, developed and commercialised until 2100? For example, how would deaths due to antibiotic resistance grow until 2100 in this pessimistic case?

Great question and something we're hoping to dive into in some more detail in a future post. Modelling on this generally isn't considered to be very reliable but as a start, the commonly sited number of 10M+ deaths by 2050 is modelled on a "worst case" scenario where there is very high levels of resistance to the most widespread infections. Therefore, this is probably fairly close to the upper end estimate that we can expect year on year. Details of the modelling here.

Drugs which aren't novel are likely to have quite short periods before they are widely resisted, due to their similarities to existing drugs. The average time to first resistance for drugs commercialised from the 1970s - 2000s was just 2 - 3 years vs. 11 years for drugs pre-1960 (although overuse will certainty have played a part in this rapid resistance as well).

Without new drugs (and accurate and cheap diagnostics to go with them) we could also enter a bad feedback loop where more resistant infections lead to doctors proscribing more 2nd, 3rd and last line antimicrobials in infections where they are only partially effective. Therefore, giving further opportunities for microbes to develop resistance than they would have had if we had more specific drugs available in the first place.

Surprised by the focus on developing new antibiotics since most antibiotics are currently given to farm animals. I initially thought reducing agriculture antibiotic usage would be the first policy pursued

Thanks for the comment Pat. Widespread use of antibiotics in animal agriculture is certainty a concern, however, the role that it plays in driving resistance overall is quite poorly understood. We think it's unlikely that because most antibiotics are used in animals therefore most resistance relevant to humans arises from their use in animals. This forum post gives a good explanation of why this is likely the case.

Given how poorly understood the drivers of resistance are (see this paper for more), and the fact that it seems unlikely that we'll be able to reduce the growth of resistance in the short term though stewardship efforts, development of new antimicrobials seems to us to be a robust option to reducing the burden of AMR.

Do you also plan to try to tackle the problem of antibiotic overdose, which also leads to AMR, and is especially rampant in India?

For any illness, bacterial or not, doctors in India typically prescribe antibiotics. The reasons for this are largely social; an antibiotic serves to eliminate any bacterial disease if somehow undiagnosed, and patients typically recover from their illnesses within the prescription period, so the doctor is judged "good" by patients. This increases the reputation and hence income of the doctor. Pharmaceutical companies reinforce this system, providing incentives to doctors for them to prescribe their antibiotics.

This ecosystem would continue to pose significant risks even if novel and better antibiotics are developed, and then made available and affordable in LMICs like India.

Thanks for the comment, ensuring better stewardship, especially in countries such as India, is definitely a really important part of combating AMR but it's not something we're planning to work on directly in the near term. The main reason for this is that as a small organisation we want to keep a narrow focus on what we think will be the most tractable option for us to have a big impact. Development of new antimicrobials seems to be a good option for this as they will always be needed, regardless of improvements to stewardship and given the lag from a policy passing to us actually seeing high-value antimicrobials on the market is likely to be at least 10 years, this felt extremely pressing to us.

We also think that new antimicrobials will play an important role in supporting stewardship and we're particularly interested in policies that can enable this. The policies we support would reduce the incentives for pharmaceutical companies to make money through sales as you've mentioned, although, they don't fully tackle the overprescribing or misprescribing issue. Additionally, more specific antimicrobials combined with better diagnostics should also help in reducing this issue.

Thanks. Could you please share the policies you mention?

Where can I find a full list of all of these small-scale projects?

Hi!

We will update our website soon. We have two small scale projects that we are running in collaboration with the Oxford Biosecurity Group. You can check out projects #2 and #3 here.

Let me know if this helps.

It will!