Crosspost of this on my blog. I'd appreciate if you could share this, as, for reasons I'll explain, I think convincing people on this issue is insanely important.

Open your mouth for the mute, for the rights of all who are destitute.

—Proverbs 31:8

Imagine that you came across 1,500 shrimp about to be painfully killed. They were going to be thrown onto ice where slowly, agonizingly, over the course of 20 minutes, they’d suffocate and freeze to death at the same time, a bit like suffocating in a suitcase in the middle of Antarctica. Imagine them struggling, gasping, without enough air, fighting for their lives, but it’s no use.

Fortunately, there’s a machine that will stun every shrimp, so that they’ll be unconscious during their deaths, rather than in extreme agony. But the machine is broken. To fix it, you’d have to spend a dollar. Should you do so? We can even sweeten the deal and imagine that the machine won’t just be used this year—it will be used year after year, saving 1,500 shrimp per year.

It seems obvious that you should spend the dollar. Extreme agony is bad. If you can prevent literally thousands of animals from being in extreme agony for the cost of a dollar—for around a fourth of the cost of a cup of coffee—of course you should do so! It’s common sense. In fact, this would be the best dollar you spent all year—every penny would save 16 shrimp from an agonizing death per year!

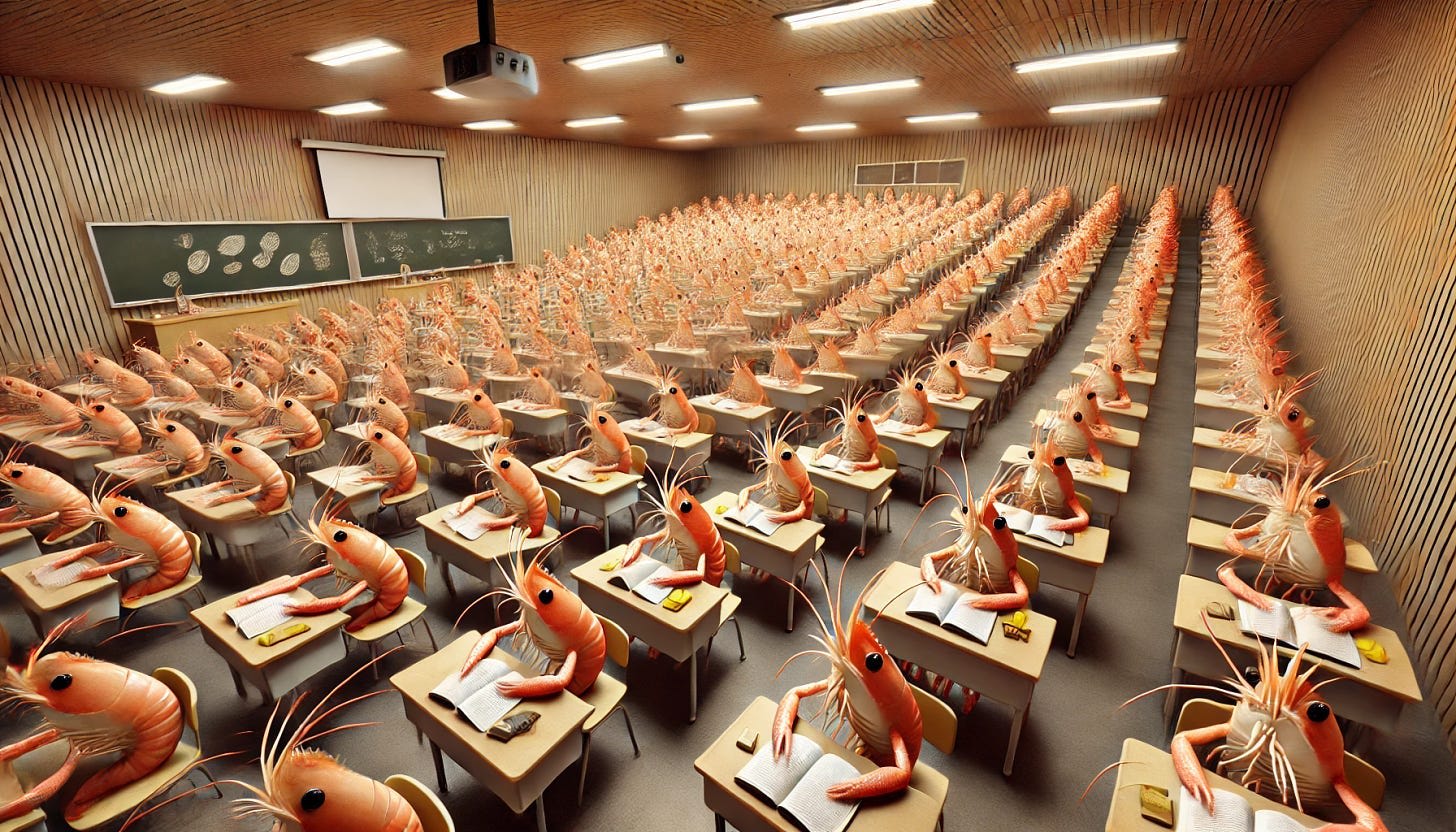

I asked chat GPT to make an image of 1,500 shrimp in a lecture hall—here’s the image, but it’s only of ~200 shrimp, so you really save much more than this:

(Above image is not realistic—shrimp do not actually attend lectures).

It turns out, this scenario isn’t just a hypothetical. One of the best charities you can give to is called the shrimp welfare project (if you want to donate monthly, you can do so here). For every dollar it gets, it saves about 1,500 shrimp from a painful death every year.

The way it works is simple and common sense: it gives stunners to companies that kill shrimp so long as they agree to use them to stun at least 120 million shrimp. They also secure welfare commitments from corporations to stop crushing the eyes of live shrimp in order to increase their fertility and to use humane slaughter (e.g. they worked with Tesco to get an extra 1.6 billion shrimp stunned before slaughter every year). In total, they’ve helped around 2.6 billion shrimp per year, despite operating on a shoestring budget.

This makes them around 30 times better at reducing suffering and promoting well-being than the highly effective animal charities focused on chicken welfare which themselves are hundreds or thousands of times more effective than the best charities helping humans. It costs thousands of dollars to save a human, but the best animal charities help hundreds of animals per dollar.

It may seem weird that the best thing to do is helping shrimp, but the world is a weird place. I’d be surprised if we got to heaven, asked God what the highest impact thing that we could have done is, and his answer was “oh, something very normal and within the Overton window.” The reason it seems crazy is because of bias; shrimp look weird and we don’t naturally empathize with them. But that’s not a reason to ignore their plight. Nearly all historical injustice can be traced to in inability to empathize with others.

Rethink Priorities, based on an incredibly thorough and detailed report, has a median estimate that shrimp suffer about 3.1% as intensely as humans (and, as I’ll discuss later, we can be quite confident that they suffer). If we multiply 1,500—the number of painful deaths averted per dollar—by 3.1%, then a dollar given to the shrimp welfare project prevents as much agony as anesthetizing 46.5 humans before they slowly suffocate to death at low temperatures, per year! That means it’s equivalent to making a human death painless every year for only two cents!

This is a highly conservative estimate. In fact, when you look at the mean estimate of how much they suffer from the same detailed report—by far the most detailed report on the subject ever compiled—it turns out that the average estimate of how much shrimp suffer is 19% as intensely as humans. That’s almost a fifth!

The mean estimate of how much shrimp suffer is a much better metric for measuring such things, for it looks at how much they suffer on average rather than the 50th percentile estimate of how much they suffer. If shrimp had a 49% chance of suffering very greatly and a 51% chance of not suffering at all, the median estimate of their suffering would be 0 while the mean estimate would be high.

Relying on the mean estimate, giving a dollar to the shrimp welfare project prevents, on average, as much pain as preventing 285 humans from painfully dying by freezing to death and suffocating. This would make three human deaths painless per penny, when otherwise the people would have slowly frozen and suffocated to death.

And remember: this is only the benefit per year! If we assume the stunners are used for ten years, then per dollar, it’s equivalent to preventing over 2,850 humans from painfully dying and by the median estimate, it’s equivalent to preventing 465 painful human deaths. This is a truly absurd amount of good—much more, per dollar per year, than every nice thing I’ve ever done interpersonally.

One objection that I think misses the mark is that there are things other than pleasure and pain that matter and for this reason, it’s better to help humans. This is ill-thought out; that pleasure and pain are not the only things that matter doesn’t mean they don’t matter at all. Preventing immense extreme suffering is very valuable even if things matter other than pleasure and pain. You could make this same argument against spending a dollar to give thousands of humans painless deaths!

Another objection is that really intense agony matters much more than mild agony—just as no number of mild headaches are as bad as a single extreme torture, perhaps no number of shrimp painfully dying is as bad as a human painfully dying. But I’m dubious of this on several counts. First, I reject the claim that no number of mild bads can add up to be as bad as a single thing that’s very bad, as do many philosophers.

Second, shrimp deaths are probably above the threshold at which suffering becomes very morally serious—it takes them longer to suffocate and freeze than it takes us, so their deaths on average last 20 minutes. Even if they suffer only 3% as intensely as we do, as per the median estimate, an experience 3% as bad as slowly suffocating to death over the course of 20 minutes at insanely low temperatures is very bad.

Third, there’s high uncertainty in the estimates. On average, they suffer 19% as intensely as we do. If a creature suffers 19% as intensely as us, we should give it significant weight, especially when there’s over a 5% that they suffer more than we do. A 5% chance that spending a dollar averts as much misery as preventing tens of thousands of human deaths—thousands per year—is a dollar well spent,

In order for this argument to work you must be very confident that:

- Lots of mild pains aren’t as bad as one extreme pain.

- The median estimate of shrimp deaths are below the threshold at which they are as important as other deaths.

- The odds shrimp’s suffering is above the threshold are very near zero.

I don’t think you should be confident in any of those things—I suspect they’re all false.

A final objection claims that shrimp welfare doesn’t matter. I think so long as shrimp can suffer, their suffering matters. Think about what it’s like to be in extreme pain—the sort of pain that characterizes suffocating or drowning. That’s a bad thing! What makes it bad isn’t our species or the fact that we’re smart but instead what the pain feels like.

If we came across very mentally disabled people or extremely early babies (perhaps in a world where we could extract fetuses from the womb after just a few weeks) that could feel pain but only had cognition as complex as shrimp, it would be bad if they were burned with a hot iron, so that they cried out. It’s not just because they’d be smart later, as their hurting would still be bad if the babies were terminally ill so that they wouldn’t be smart later, or, in the case of the cognitively enfeebled who’d be permanently mentally stunted.

Can shrimp suffer? Almost definitely yes. This is the plurality view among those who have studied it for a simple reason: there’s every evolutionary reason to expect them to suffer and in every way they behave like they do suffer. It’s beneficial for a shrimp to be able to suffer, just like it’s beneficial for you to suffer; it helps them avoid injury. Thus, it would be a bit surprising if they didn’t suffer.

Nothing about how shrimp behave makes sense except on the assumption that they suffer. If injured, shrimp will nurse the wound and behave differently, just as we do. Shrimp respond to painkillers, and shockingly will even self-administer painkillers if they’re hurt, in exactly the way we’d expect them to if they felt pain.

Shrimp have most features that we’d expect to go with consciousness. They communicate, integrate information from different senses into one broad pictures, make trade-offs between pain and various goods, display anxiety, have personal taste in food, and release stress hormones when scared. Other crustaceans behave like we do when we’re in pain, being likelier to abandon a shell when they’re given more intense electric shocks, such that their abandonment is a function of both the desirability of the shell and greatness of the shocks. One study looked at the seven criteria that are the best indicators of pain and concluded that crustaceans possess all of them, including being able to communicate and remember and avoid places where they were in pain.

Even if you’re not sure that they can suffer, as long as there’s a chance, the shrimp welfare project is still insanely impactful—if a dollar had even a 20% chance of averting thousands of painful deaths, it would be well spent.

Despite the fact that we kill many trillions of shrimp every single year, the shrimp welfare project, the only project helping shrimp avoid extreme suffering, is seriously underfunded. It’s hugely dependent on a few big donors who have cut funding recently, utterly devastating it. As a result, it needs small, grass-roots funders like you to prevent millions of animals from being subjected to an incredibly cruel fate, like being slowly suffocated and froze to death and having their eyes crushed.

Thousands saved per dollar per year really scales. My articles are generally read by about 2,000 people—this means if you all give ten dollars to the shrimp welfare project, that would save 30 million shrimp from a cruel fate every single year. For the cost of a car, the number of shrimp that you could massively help is more than the population of California. This is one of the few cases where a single person like you or me can dramatically help tens of millions!

One way to see how good different charities are is to imagine that after you died, you had to live the life of every creature on earth. This forces you to empathize not just with those that are salient, but with everyone. You’d have to live the perspective of everyone you helped and hurt, of everyone mistreated and treated well. In such a world, one of my profoundest regrets would be that I did nothing about the millions of shrimp that I would have to spend millions of years living as

Shrimp are a test of our empathy. Shrimp don’t look normal, caring about them isn’t popular, but basic ethical principles entail that they matter. This is one of the rare cases where you can prevent tens of thousands of terrible things from happening for just a dollar. I hope you’ll join me! I’m giving about 50 dollars per month to the shrimp welfare project, which helps around 1.3 million shrimp per year:

(Crossposted from twitter)

While I'm a big fan of SWP and have donated to them myself, I am skeptical of claims like

I greatly appreciate @Vasco Grilo🔸 for writing up his analysis, but I don't think that most people would agree with some of the assumptions made in it regarding pain intensity:

Vasco estimates that asphyxiating shrimp experience about 7.5 minutes of excruciating pain, and weights this as 10000x worse than disabling pain, which is the maximum pain experienced by a chicken during a keel bone fracture or death from heat exhaustion (in the data used to generate the THL numbers). Moreover, the data he relies on for the cost effectiveness of GiveWell top charities does not allow for the existence of states worse than death. This means that he's estimating that the pain experienced during asphyxiation is 100000x the worst pain prevented by GiveWell. This seems highly implausible to me. Surely dying of malaria or diarrheal disease involves some pain that is within 100000x the intensity of suffocation (and indeed WFP estimates that sepsis in a chicken involves excruciating pain, so I would expect that sepsis in a human does as well).

None of this is to say that SWP is ineffective, merely that the cost-effectiveness ratios compared to other EA top charities citied here seem overly high to me.

Thanks, Matt!

Your objection is fair, in that I strongly agree there are states humans can be in that are much worse than death. However, I think the math works out such that the points you raise have a negligible effect on my results. Assuming the human deaths prevented by GiveWell's top charities are as painful as a fraction of the welfare range of humans as shrimp deaths from air asphyxiation slaughter as a fraction of the welfare range of shrimps, the suffering involved in one death prevented by GiveWell's top charities would be equivalent to 1.44 DALYs (= 1.26*10^4/24/365.25). To estimate the cost-effectiveness of GiveWell's top charities, I assumed saving one life is as good as averting 51 DALYs:

Consequently, human deaths prevented by GiveWell's top charities being relatively as painful as shrimp deaths from air asphyxiation would only increase the cost-effectiveness of GiveWell's top charities by at most 2.82 % (= 1.44/51). I say at most because GiveWell already partially accounts for the benefits of decreasing morbidity (besides those of decreasing mortality).

I think that ratio underestimates the promise of the Shrimp Welfare Project (SWP) relative to chicken welfare campaigns. My analysis of SWP uses my updated intensity of disabling pain (10 times as intense as fully healthy life), which is 10 % of my previous intensity that I used in my analysis of chicken welfare campaigns. I plan to post an updated cost-effectiveness analysis of chicken welfare campaigns in 1 or 2 weeks.

Thanks Vasco. After thinking about the numbers myself, I agree that allowing for states worse than death can't on its own do a lot to make the numbers comparable between GiveWell and SWP. I do actually think it would move the numbers more than you're accounting for there, both because the deaths prevented by GiveWell top charities might involve more than 7.5 minutes of excruciating pain and because GiveWell top charities prevent a lot of morbidity among people who end up surviving (and I think they're significantly underweighting the value of this, e.g. clean water interventions prevent about 6 person-years of being sick with waterbone illnesses for everyone person who dies, and I would significantly prefer to be in a dreamless sleep than be conscious with a severe enteric infection.[1] But the DALY weight for severe diarrheal illness is 0.247, implying 3/4ths the wellbeing[2] of being fully healthy). But this is at most going to change the cost-effectiveness of GiveWell top charities by a factor of 2, not 4 OOMs.

As for the 10000x difference in weights between disabling and excruciating pain, I have to admit I'm pretty confused here. On the one hand, it strikes me as fundamentally implausible that suffocating is 10000x worse than dying of heatstroke. On the other hand, some of my intuitions do lean towards not being willing to endure e.g. burning to death for almost anything else. I'll need to spend some time reviewing the literature before I try and make further sense of how to best make these tradeoffs.

Thanks again for all your work and engagement here, I think it's genuinely quite valuable to be having these conversations!

I took some notes on my willingness to make these tradeoffs when I was recently sick with norovirus and am hoping to write a short post on this soon!

DALY weights are a measure of health status, not wellbeing, but that hasn't stopped anyone from using them as a unit of wellbeing

I had a look at the literature a few weeks ago (skimming some of the studies mentioned here), and, as a result, updated to an intensity of disabling pain 10 % as high as my original one (from 100 to 10 times as intense as fully healthy life). It looks like there are no studies informing the intensity of excruciating pain:

Likewise. Thanks, Matt!

I liked your analysis. No worries if this would be too difficult, but it might be helpful to make a website where you can easily switch around the numbers surrounding how the different kinds of suffering compare to each other and plug in the result.

I agree with most of your estimates but I think you probably underrated how bad disabling pain is. Probably it's ~500 times worse than normal life. Not sure how that would affect the calculations.

Thanks, Omnizoid. Feel free to update my sheet with yout own numbers (although I understand a website would be more handy). If you like me think that excruciating pain is super bad, the cost-effectiveness is essentially proportional to the intensity of excruciating pain (the intensity of disabling pain does not matter), and the welfare range of shrimp. So, for example, if you think excruciating pain is 10 % as intense as I do, and you believe the welfare range of shrimp is 2 times as high as I assumed, then the cost-effectiveness would become 20 % (= 0.1*2) as high.

I tried to do that but ended up a bit confused about what numbers I was using for stuff (I never really properly learned how spreadsheets worked). If I agree with you about the badness of excruciating pain but think you underrated disabling pain by ~1 order of magnitude, do the results still turn out with shrimp welfare beating other stuff?

Yes:

Gotcha, makes sense! And I now see how to manipulate the spreadsheet.

I think one could probably push back on whether 7.5 minutes of [extreme] pain is a reasonable estimate for a person who dies from malaria, but I think the bigger potential issue is still that the result of the BOTEC seems highly sensitive to the "excruciating pain is 100,000 times worse than fully healthy life is good" assumption - for both air asphyxiation and ice slurry, the time spent under excruciating pain make up more than 99.96% of the total equivalent loss of healthy life.[1]

I alluded to this on your post, but I think your results imply you would prefer to avert 10 shrimp days of excruciating pain (e.g. air asphyxiation / ice slurry) over saving 1 human life (51 DALYs).[2]

If I use your assumption and also value human excruciating pain as 100,000 times as bad as healthy life is good,[3] then this means you would prefer to save 10 shrimp days of excruciating pain (using your air asphyxiation figures) over 4.5 human hours of excruciating pain,[4] and your shrimp to human ratio is less than 50:1 - that is, you would rather avert 50 shrimp minutes of excruciating pain than 1 human minute of excruciating pain.

To be clear, this isn't a claim that one shouldn't donate to SWP, but just that if you do bite the bullet on those numbers above then I'd be keen to see some stronger justification beyond "my guess" for a BOTEC that leads to results that are so counterintuitive (like I'm kind of assuming that I've missed a step or OOMs in the maths here!), and is so highly sensitive to this assumption.[5]

Air asphyxiation: 1- (5.01 / 12,605.01) = 0.9996

Ice slurry: 1 - (0.24 / 604.57) = 0.9996

1770 * 7.5 = 13275 shrimp minutes

13275 / 60 / 24 = 9.21875 shrimp days

There are arguments in either direction, but that's probably not a super productive line of discussion.

51 * 365.25 * 24 * 60 = 26,823,960 human minutes

26,823,960 / 100,000 = 268.2396 human minutes of excruciating pain

268.2396 / 60 = 4.47 human hours of excruciating pain

13275 / 268.2396 = 49.49 (shrimp : human ratio)

Otherwise I could just copy your entire BOTEC, and change the bottom figure to 1000 instead of 100k, and change your topline results by 2 OOMs.

Thanks, Bruce.

My calculation above assumed 7.56 min (= 0.126*60) of excruciating pain, not just "pain". Examples of excruciating pain include "scalding and severe burning events [in large parts of the body]", or "dismemberment, or extreme torture".

I had to guess the intensity of excruciating pain because there is basically no empirical data informing potential estimates.

I agree my guess is speculative. However, if one wants to argue that I overestimated the cost-effectiveness of SWP, one has to provide reasons for my guess overestimating the intensity of excruciating pain. I do not think claiming the results are unintuitive is a good way of doing this. In the context of global health and development, it would not make much sense to dismiss GiveWell's conclusion that one can save a life for 5 k$ just because it is unintuitive that one can save 10 lives for the cost of a BMW. Instead, it would be better to critique the inputs that went into the cost-effectiveness analysis. I know you are doing better than this, because you are critiquing intermediate results instead of the final cost-effectiveness. However, I would say it would be better if you focussed on criticising my assumption that excruciating pain is 100 k times as intense as fully healthy life, or, equivalently, the direct implication that 1 day of fully healthy life is neutralised by 0.864 s (= 24*60^2/(100*10^3)) of excruciating pain.

If you did that, SWP would still be 434 (= 43.4*10^3*10^3/(100*10^3)) times as cost-effective as GiveWell's top charities. I think it is also worth wondering about whether you trully believe that updated intensity. Do you think 1 day of fully healthy life plus 86.4 s (= 0.864*100*10^3/100) of scalding or severe burning events in large parts of the body, dismemberment, or extreme torture would be neutral?

Ah my bad, I meant extreme pain above there as well, edited to clarify! I agree it's not a super important assumption for the BOTEC in the grand scheme of things though.

I don't actually argue for this in either of my comments.[1] I'm just saying that it sounds like if I duplicated your BOTEC, and changed this one speculative parameter to 2 OOMs lower, an observer would have no strong reason to choose one BOTEC over another just by looking at the BOTEC alone. Expressing skepticism of an unproven claim doesn't produce a symmetrical burden of proof on my end!

Mainly just from a reasoning transparency point of view I think it's worth fleshing out what these assumptions imply and what is grounding these best guesses[2] - in part because I personally want to know how much I should update based on your BOTEC, in part because knowing your reasoning might help me better argue why you might (or might not) have overestimated the intensity of excruciating pain if I knew where your ratio came from (and this is why I was checking the maths and seeing if these were correct, and asking if there's stronger evidence if so, before critiquing the 100k figure), and because I think other EAF readers, as well as broader, lower-context audience of EA bloggers would benefit from this too.

Yeah, I wasn't making any inter-charity comparisons or claiming that SWP is less cost-effective than GW top charities![3] But since you mention it, it wouldn't be surprising to me if losing 2 OOMs might make some donors favour other animal welfare charities over SWP for example - but again, the primary purpose of these comments is not to litigate which charity is the best, or whether this is better or worse than GW top charities, but mainly just to explore a bit more around what is grounding the BOTEC, so observers have a good sense on how much they should update based on how compelling they find the assumptions / reasoning etc.

Nope! I would rather give up 1 day of healthy life than 86 seconds of this description. But this varies depending on the timeframe in question.

For example, I'd probably be willing to endure 0.86 seconds of this for 14 minutes of healthy life, and I would definitely endure 0.086 seconds of this than give up 86 seconds of healthy life.

And using your assumptions (ratio of 100k), I would easily rather have 0.8 seconds of this than give up 1 day of healthy life, but if I had to endure many hours of this I could imagine my tradeoffs approaching, or even exceeding 100k.

I do want to mention that I think it's useful that someone is trying to quantify these comparisons, I'm grateful for this work, and I want to emphasise that these are about making the underlying reasoning more transparent / understanding the methodology that leads to the assumptions in the BOTEC, rather than any kind of personal criticism!

Though I am personally skeptical of a 50:1 shrimp:human tradeoff

E.g. is this the result of a personal time trade-off exercise?

I explicitly say "To be clear, this isn't a claim that one shouldn't donate to SWP". I'm a big fan of SWP!

Thanks, Bruce! Makes sense. I have now clarified in the post that the guesses for the pain intensities come from my personal time trade-offs:

0.1 s of excruciating pain intuitively passes very quickly, so I can easily imagine it being less than 100 times as bad as 10 s (= 0.1*100) of excruciating pain. However, I think intuitions like this are misguided holding the intensity of pain constant (i.e. only varying duration). For example, if 1 min in strong pain is 100 times as bad as 1 min in weak pain, and strong and weak pain have each a constant intensity (instead of referring to ranges of intensities), N min in strong pain should be 100 times as bad as N min in weak pain. Saying otherwise implies that the badness of 1 min in strong pain depends on how many minutes of strong pain preceded that 1 min, which contradicts the assumption that strong pain has a constant intensity.

I think 0.1 s of excruciating pain does not feel bad because one wrongly imagines the memory of the pain afterwards, which may not be so bad because 0.1 s is too little time to form memories. In addition, one may imagine that some time is needed to reach the intensity of excruciating pain, such that only a small fraction of the 0.1 s are actually excruciating pain, but the thought experiment requires 0.1 s of actual excruciating pain.

Published.

I just want to thank you for such an impressive forum post! I think Shrimp Welfare is very interesting and it has been an eye-opener for me when it comes to animal welfare. My own area is global / public health in different forms, but I will use some of the examples mentioned here in my lectures about global health and economic evaluations for my students if it is okay for you? I think it might be an eye-opener for some of them as well.

Yeah sure! Thanks so much!

Nice post, Omnizoid! Relatedly, I estimated Shrimp Welfare Project’s (SWP's) Humane Slaughter Initiative is 64.3 k times as cost-effective as GiveWell’s top charities. My annual donations will most likely go to SWP.

Very convincing post ! The case for helping shrimp is strong.

Indeed, if people focused on having an impact won't support this project, who else will ?

I also donated to them this year.

Awesome!

Thanks for the great post, Omnizoid!

I have updated my cost-effectiveness analysis of corportate campaigns for chicken welfare. Now I estimate the Shrimp Welfare Project is 412 and 173 times as cost-effective as broiler welfare and cage-free campaigns (instead of "around 30 times better"), and that these are 168 and 462 times as cost-effective as GiveWell’s top charities (i.e. more like "hundreds" instead of "hundreds to thousands" of times more cost-effective than the best charities helping humans).