Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

They’re imperfect agents of change

The world’s three largest animal welfare groups are under attack. Their antagonists are not factory farmers, but other animal groups. And the ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA stand accused not of hurting farmers, but of hurting animals, through their work with GAP and RSPCA Assured, which certify animal products as being less cruelly produced.

The attacks began last summer when the UK animal rights group Animal Rising released a report and footage showing abuses on RSPCA Assured farms. They’ve since forced the RSPCA to cancel its 200th year celebrations, plastered portraits of RSPCA patron King Charles, and persuaded the ceremonial president and two vice-presidents of the RSPCA to resign in protest. (To understand their perspective, I recommend this interview with Animal Rising co-director Ben Newman.)

A few months ago, PETA launched a new front in the war, taking out full-page ads in the The New York Times and The Washington Post slamming the ASPCA and HSUS for associating with GAP. (Ingrid Newkirk laid out PETA’s case here.) PETA activists have since picketed the homes of the CEOs of both groups, disrupted the organizations’ fundraising events, and persuaded actor James Cromwell to throw away an HSUS award.

With friends like these

I originally planned to write a newsletter about infighting. I would have argued that our movement lacks the resources to spare some to attack one another. And I would have cited a 2023 survey by the Social Change Lab, in which 120 social movement academics rated “internal conflict or movement infighting” as the gravest internal threat to social movement success.

But there’s an irony in criticizing infighting: you risk becoming an infighter yourself. And I’m hardly an impartial observer: I used to work at HSUS, and at Open Philanthropy we’ve funded GAP, HSUS, the RSPCA, and RSPCA Assured — but not Animal Rising or PETA. It’s too easy to decry infighting when it’s the other side doing it. So instead I’ll refer you to my favorite scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, in which the People’s Front of Judea derides the Judean People’s Front.

I also don’t want to attack Animal Rising or PETA. Animal Rising has mobilized thousands of young people to decry our society’s indifference to mass animal suffering. PETA put animal rights on the map, trained some of our movement’s best activists (including the CEO of HSUS), and won the first corporate cage-free victories.

Instead, I want to engage with their criticisms of GAP and RSPCA Assured. Broadly, they make three: (1) the certifications are misleading, (2) they fail to stop cruelty, and (3) the involvement of the ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA legitimizes them — and meat eating. I’ll take each in turn.

“Humanely raised” and misleadingly labeled

Animal Rising and PETA are right about one thing: humane labels can be misleading. Put aside the semantic debate about whether meat can ever be “humane”; I suspect most consumers think certification labels mean more than they do. In a 2021 survey by Farm Forward, a GAP board member-turned-skeptic, 39% of respondents mistakenly thought that GAP labels mean that animals are raised with consistent access to the outdoors.

Animal Rising also points out that the RSPCA Assured website claims “we do not allow factory farming on our scheme.” That’s a stretch. Most GAP and RSPCA Assured meat comes from higher-welfare indoor farms that still look an awful lot like factory farms.

I’d prefer more specific labels. When GAP started, its labels listed welfare levels from one to five and explained what each level meant (“Step 3, enhanced outdoor access”). But the labels now simply read “Animal Welfare Certified,” regardless of the GAP level, perhaps because marketers at Whole Foods, which sells most GAP meat, saw that ambiguity doesn’t drive sales.

The biggest obstacle to fixing this is that everyone else is doing it. Chicken certified by American Humane Certified, which has much weaker standards than GAP, is labeled “humanely raised on family farms.” This works: the same Farm Forward survey found that consumers thought that American Humane Certified was at least as strong as GAP. So if GAP weakens its label, consumers may just switch to worse meat with better labels.

The answer is for the government to step in. The USDA recently tried to do so, but ultimately gave way to industry pressure to allow any label the industry believes is true. The EU and UK are considering bolder reforms: to create multi-tiered welfare labeling schemes, though the industry is lobbying to make them voluntary. For better models look to Denmark, whose three-tier scheme is voluntary but widely followed, and Germany, which just enacted a mandatory five-tier scheme for pork.

In the meantime, retailers should stop the sale of misleadingly labeled meat. Whole Foods led the way in this, requiring all meat in stores to be labeled at its GAP levels. But while GAP was recently finalizing new stronger rules, Whole Foods announced that it would allow for other weaker, but better-sounding, meat certifications. The test for retailers should be simple: can consumers accurately work out the animals’ welfare from the label? I suspect most current labels fail that standard.

Imperfect progress

To Animal Rising and PETA, such label fixes are not enough. Their complaint is not just with GAP and RSPCA Assured’s labels, but the schemes themselves. They point out that the schemes’ own standards allow for continued cruelties, like keeping animals permanently crowded in giant barns.

This is true. But for me the question is not whether these certifications end all cruelty, but whether they reduce it. They do: their standards prohibit some of the worst cruelties common on standard factory farms, like battery cages and gestation crates — and none of the recent investigations I’ve seen found these on certified farms. RSPCA Assured farms are already free of frankenchickens and GAP farms will be by 2030.

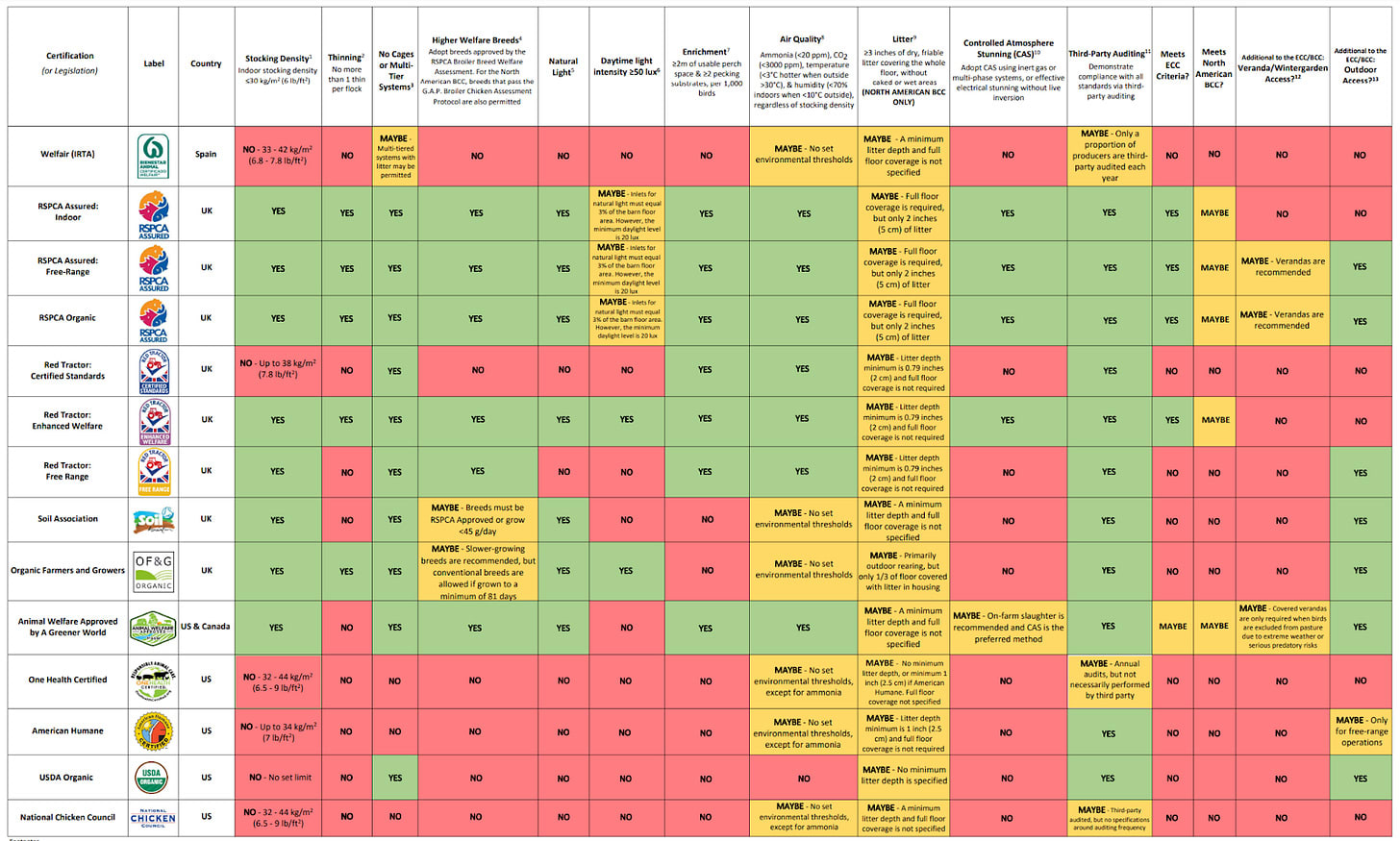

Of course, GAP and RSPCA Assured could raise their standards. And both are. But if they go too far too fast, costs and prices will rise, and farms and consumers will defect to the biggest competitors of each scheme: American Humane Certified and Red Tractor, each of which has much weaker standards (see chart below). Overall, animal welfare would get worse, not better.

This doesn’t mean we should just accept low standards. But the right target is not the certifiers but the retailers. As corporate campaigns push retailers to remove the cruelest products from their shelves — as most UK retailers have now done with caged eggs — certifiers can raise their standards without getting undercut by lower-welfare competition.

Still, Animal Rising and PETA have a point that many GAP and RSPCA Assured farms aren’t following the standards they claim to. Their investigations have found repeated violations of standards requiring things like care for sick animals, and I doubt that things are better when investigators aren’t around. The RSPCA acknowledged as much in sanctioning nine of the 40 farms Animal Rising investigated and kicking another three out of the scheme.

But the answer to this is more certification, not less. Animal Rising’s campaign has led RSPCA Assured to announce an upgraded enforcement regime, including more unannounced audits and greater use of CCTV. This is good. And soon AI tools will allow for certifiers to continuously monitor conditions in every certified barn. When they do, the certifiers should adopt them.

Sins of omission

None of this explains why the ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA need to be involved with the certification schemes. Animal Rising and PETA argue that their involvement serves no purpose other than to legitimize the schemes — and meat eating itself.

I’m sympathetic to Animal Rising’s case here. They’ve likened stamping meat packages with the RSPCA’s logo to stamping cigarettes with the British Heart Foundation’s logo. I don’t think it’s quite the same, but I suspect future generations may disagree. RSPCA Assured used to be called “Freedom Food,” and I think a name like that would avoid conferring the RSPCA’s hard-earned legitimacy on a controversial product.

I’m less sympathetic to PETA’s case. I don’t think anyone buys GAP certified products because the ASPCA and HSUS are on GAP’s board. Indeed, I doubt many people even knew that the groups were associated before PETA’s campaign. I also don’t think endorsing less cruel standards means endorsing meat, just as I don’t think public health groups endorsed junk food when they joined Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! initiative, which partnered with Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and others to reduce sugar and sodium in their foods.

And I doubt that many people care what the big animal groups think they should eat. If they did, they’d get a clear message: the ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA all say people should eat less meat. The HSUS runs the nation’s largest institutional meat reduction program, and has long endured industry attacks for being anti-meat, as have more recently the ASPCA and RSPCA.

Now that these groups face attacks from both sides, they may be tempted to just avoid controversial work for farmed animals. Nonprofits generally only get attacked for action, not inaction. Run a rescue group that refuses to take in unadoptable animals, and no one will complain. Run a shelter of last resort that euthanizes unadoptable animals, and everyone will. The easiest option would be for the big groups to dump the certification schemes.

Easy, but wrong. The predictable result would be that the schemes would either cease to exist or be taken over by industry. Without the RSPCA’s support, RSPCA Assured would likely fold, its farms moving over to the weaker Red Tractor certification. Without the ASPCA and HSUS, GAP would fall more firmly under the control of Whole Foods and big producers. Neither outcome seems good for animals.

An end to one percent solutions

I think the most compelling case against the certification schemes is that they cause us to focus in the wrong place: on individual consumer decisions rather than system-wide changes. Just as veganism has remained stubbornly stuck at around one percent of the US population, so has consumption of truly higher-welfare meat. The reality is that we can’t end factory farming one purchasing decision at a time.

Instead we need to focus on the biggest levers of social change, like laws, corporate policies, and technology. The certifiers have a role to play in all three. Their voluntary baseline standards can form the basis for future laws, just as the voluntary HACCP food safety system later became part of US and EU regulations. They can audit companies’ implementation of welfare pledges like the Better Chicken Commitment. And they can facilitate the adoption of new technology, just as Germany’s KAT certification recently helped implement the end of the killing of day-old male chicks in the country.

Animal Rising and PETA also have a major role to play. Their institutional goals will differ: Animal Rising’s institutional campaigns have focused on getting UK universities to go plant-based, while PETA’s have lately focused on getting US retailers to stop selling coconut milk made with forced monkey labor. They both also use shock tactics to wake people up to the cruelties of factory farming — just as the best radical campaigns throughout history have done. Indeed, PETA videos played a major role in educating me about factory farming 25 years ago.

It’s hard to strike the right balance between idealism and pragmatism. PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk once said of Temple Grandin, who designs more humane slaughterhouses, that she “has done more to reduce suffering in the world than any other person who has ever lived.” Dr. Grandin in turn has told me that her work would be impossible without the pressure that advocacy groups put on food companies to reform. We need both approaches — and more.

In a world largely indifferent to factory farming, we are a small — but growing — group fighting it. We need all the help we can get: from vegans and omnivores, moderates and radicals, urbanites and farmers. We also need to experiment with many different tactics to maximize our shots on goals. This will cause plenty of healthy disagreement. And that’s ok. But I hope we can remember that the things we agree on — that animals’ suffering matters, that factory farming is a moral atrocity, and that it must end — are ultimately much more important.

Thanks to Animal Rising’s Ben Newman and Simple Heart’s Wayne Hsiung for reviewing a draft of this essay. Their clarifications and suggestions improved it, though they still disagree on several key points.

Just wanted to express that I really appreciate your newsletter as a source of thought leadership. Often I find myself wondering about one aspect of the animal advocacy movement or another, and then a few months later you provide a thoughtful summary of the state of play and next steps.

This section of Lewis' thoughtful piece stood out to me:

"None of this explains why the ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA need to be involved with the certification schemes. Animal Rising and PETA argue that their involvement serves no purpose other than to legitimize the schemes — and meat eating itself.

"I’m sympathetic to Animal Rising’s case here. They’ve likened stamping meat packages with the RSPCA’s logo to stamping cigarettes with the British Heart Foundation’s logo. I don’t think it’s quite the same, but I suspect future generations may disagree. RSPCA Assured used to be called “Freedom Food,” and I think a name like that would avoid conferring the RSPCA’s hard-earned legitimacy on a controversial product."

This feels like a potentially actionable step that the RSPCA could take. Perhaps they could spin-out their accreditation scheme, under a new branding. This might deliver the purported benefits of certification, without the immense weirdness of the RSPCA themselves being seen to endorse the commodification and slaughter of animals.

The RSPCA's brand/legitimacy/"halo" is amazingly strong in the UK, amongst the general population. It's a much-loved, maybe even adored and treasured, national institution. It's hard to quantify, but it seems very plausible that affixing that wonderful brand reputation to packages containing the dead bodies of slaughtered animals really does do lasting damage to our collective, long-term efforts to end animal use and abuse. Having the RSPCA logo on dead animal products on the supermarket shelves seems likely to legitimise the idea that it's morally OK to eat animals - and that any animal with an RSPCA-assured logo on its dead body had an overall net-positive life, which seems far from certain.

I wonder if spinning-out the accreditation scheme is a 'compromise' that the RSPCA might consider making? It would be a (partial) win-win for everyone. The purported benefits of accreditation would still get delivered. The Animal Rising side of the debate would be (partially) satisfied. The controversy and reputational damage to the RSPCA would be somewhat assuaged. It wouldn't be a complete "win" for anyone, but it seems like most parties to this debate would think it's an improvement on the status quo.

This seems false to me, without the RSPCA's brand behind it, consumers would be less willing to pay a premium for the products, and supermarkets would be less keen to stock them.

Good catch. I think you are probably right, and that this point should be taken into consideration when thinking about whether the benefits of having the RSPCA logo on the dead animals outweighs the dis-benefits.

The original post would probably be better written as "*At least some of* the purported benefits of accreditation would still get delivered."

I wonder, empirically, how big a difference the RSPCA vs non-RSPCA branding would make - I struggle to do anything other than guess about this.

Perhaps there are some consumers who might not buy the animals at all if they weren't endorsed by the RSPCA - though I fear this might be a (very) low number, at least in the immediate term. Over the longer term, though, in terms of cultural shifts and norms, the number could be higher. Hhhmm...

Thank you, some time ago I wrote this piece, thinking that nobody in the field was working in credible certifications. If farmers become used to welfare certifications, soon they can discover that it is in their collective economic interest to support it (as electric utilities have done with climate change).

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/L6wdRBCh3izCD244t/farmers-in-the-animalist-coalition

Your article is extremely useful! Thx.

Executive summary: The ongoing criticism of animal welfare certification schemes by groups like Animal Rising and PETA highlights valid concerns about misleading labels and the limitations of these programs, but the involvement of major organizations such as ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA is crucial for incremental progress and systemic change in reducing animal suffering.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.