Summary

At the Happier Lives Institute, we look for the most cost-effective interventions and organisations that improve subjective wellbeing, how people feel during and about their lives[1]. We quantify the impact in ‘Wellbeing Adjusted Life-Years’, or WELLBYs[2]. To learn more about our approach, see our key ideas page and our research methodology page.

Last year, we published our first charity recommendations. We recommended StrongMinds, an NGO aiming to scale depression treatment in sub-saharan Africa, as our top funding opportunity, but noted the Against Malaria Foundation could be better under some assumptions. This year, we maintain our recommendation for StrongMinds, and we’ve added the Against Malaria Foundation as a second top charity. We have substantially updated our analysis of psychotherapy, undertaking a systematic review and a revised meta-analysis, after which our estimate for StrongMinds has declined from 8x to 3.7x as cost-effective as cash transfers, in WELLBYs, resulting in a larger overlap in the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds and AMF[3]. The decline in cost-effectiveness is primarily due to lower estimated household spillovers, our new correction for publication bias, and the prediction that StrongMinds might have smaller than average effects.

We’ve also started evaluating another mental health charity, Friendship Bench, an NGO that delivers problem-solving therapy in Zimbabwe. Our initial estimates suggest that the Friendship Bench may be 7x more cost-effective, in WELLBYs, than cash transfers. We think Friendship Bench is a promising cost-effective charity, but we have not yet investigated it as thoroughly, so our analysis is more preliminary, uncertain, and likely to change. As before, we don’t recommend cash transfers or deworming: the former because it’s likely psychotherapy is several times more cost-effective, the latter because it remains uncertain if deworming has a long-term effect on wellbeing.

This year, we’ve also conducted shallow investigations into new cause areas. Based on our preliminary research, we think there are promising opportunities to improve wellbeing by preventing lead exposure, improving childhood nutrition, improving parenting (e.g., encouraging stimulating play, avoiding maltreatment), preventing violence against women and children, and providing pain relief in palliative care. In general, the evidence we’ve found on these topics is weaker, and our reports are shallower, but we highlight promising charities and research opportunities in these areas. We’ve also found a number of less promising causes, which we discuss briefly to inform others.

In this report, we provide an overview of all our evaluations to date. We group them into two categories, In-depth and Speculative, based on our level of investigation. We discuss these in turn.

In-depth evaluations: relatively late stage investigations that we consider moderate-to-high depth.

- Top charities: These are well-evidenced interventions that are cost-effective[4] and have been evaluated in medium-to-high depth. We think of these as the comparatively ‘safer bets’.

- Promising charities: These are well-evidenced opportunities that are potentially more cost-effective than the top charities, but we have more uncertainty about. We want to investigate them more before recommending them as a top charity.

- Non-recommended charities: These are charities we’ve rigorously evaluated but the current evidence suggests are less cost-effective than our top charities.

Speculative evaluations: early stage investigations that are shallow in depth.

- Promising bets: These are high-priority opportunities to research because we think they’re potentially more cost-effective than our current recommendations. We mention them for donors interested in ‘high-risk, potentially high-reward’ giving.

- Less promising interventions: These are interventions we’ve looked into briefly but have unpromising cost-effectiveness, limited evidence, or unactionable funding opportunities. We share these as a point of comparison, as we expect donors will want to know about ‘misses’ as well as ‘hits’.

In-depth evaluations

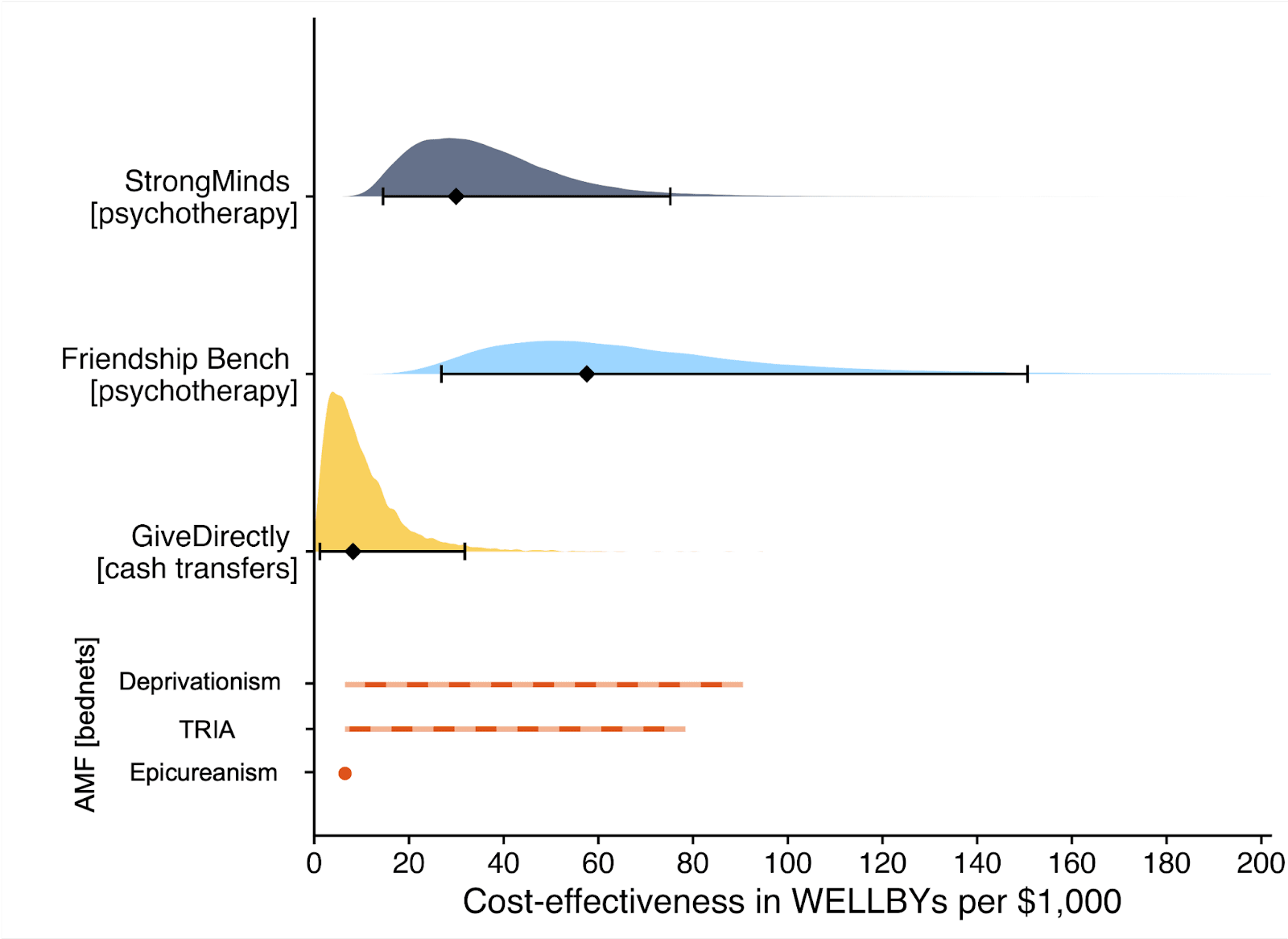

We present our cost-effectiveness estimates for charities we’ve evaluated in medium to high depth in Figure 1. We discuss each charity in turn in the following sections.

Figure 1: Comparison of the cost-effectiveness of the charities.

Note. The diamonds represent the central estimate of cost-effectiveness (i.e., the point estimates). The shaded areas are probability density distribution and the solid whiskers represent the 95% confidence intervals for StrongMinds, Friendship Bench, and GiveDirectly. The lines for AMF (the Against Malaria Foundation) are different from the others[5]. Deworming charities are not shown, because we are very uncertain of their cost-effectiveness.

1. Top charities

Our top charities are well-evidenced opportunities that are cost-effective and have been evaluated in medium-to-high depth. Readers should be aware that this doesn’t mean we think these interventions are the best there is, only that these are the best we’ve found so far. Research looking into the best ways to help people become happier, as measured in WELLBYs, is novel in general; we only made our first recommendation in 2022 and there is plenty more to do.

1.1 StrongMinds psychotherapy

StrongMinds is an NGO that treats women for depression via six weeks of in-person group psychotherapy (g-IPT; WHO, 2016) programmes across Uganda and Zambia. We recommended StrongMinds last year, and we do so again this year.

However, this year we conducted a substantial update to our evaluation of psychotherapy in general and StrongMinds in particular (McGuire et al. 2023c). This update involved several major methodological extensions of our previous work:

- Systematically reviewing the literature to update the evidence for the individual (39 → 74 RCTs) and household effects (2 → 5 RCTs).

- Correcting for publication bias, which leads to a 36% discount.

- And combining the general and charity specific evidence using Bayesian methods (this weighs the evidence in a formal, quantitative way, rather than relying on us to weigh the evidence with our subject best guess).

We estimate that StrongMinds has a total effect per treatment of 2.15 WELLBYs (this includes the effect on the recipient and spillover effects on household members). This is considerably lower than our previous estimate of 10.49 WELLBYs (an 80% reduction) for the following reasons: (1) we now estimate a smaller household spillover ratio of 16% (before 38%), (2) we predict that StrongMinds has smaller than average effects[6], and (3) we now include a 36% discount for publication bias. On the other hand, the costs per person treated for StrongMinds has declined to $63 (previously $170), which increases its cost-effectiveness.

We now estimate that a $1,000 donation results in 30 WELLBYs (95% CI: 15, 75), a 52% reduction from our previous estimate of 62 (see our changelog website page). Hence, comparing the point estimates, we now estimate that StrongMinds is 3.7x (previously 8x) as cost-effective as GiveDirectly – which produces 8 (95% CI: 1, 32) WELLBYs per $1,000 (McGuire et al., 2022b)[7].

We think the quality of evidence supporting the effect of psychotherapy interventions is moderate. This is because the individual effects of psychotherapy are well evidenced (77 RCTs, participants = 28,491). However, there is currently no charity-specific evidence for StrongMinds as details of the forthcoming Baird et al. RCT are not public. Instead, we use a placeholder study that deploys the same intervention as StrongMinds, but then discount our placeholder study by 95% as a way of anticipating the prospect that the Baird et al. study will find a small effect (according to publicly available information, it has found a “small” effect). There are also only 5 RCTs for household spillover effects in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The lower quality charity specific and spillover evidence lowers our judgement of the evidence’s quality.

We view the depth of our analysis of psychotherapy and StrongMinds as ‘moderate-to-high-depth’. We believe that we have reviewed most of the available evidence. However, note that our new report is a preliminary analysis we are releasing in time for the 2023 giving season; we plan to submit it to an academic journal in 2024 and expect the analysis to evolve somewhat.

Overall, we think funding StrongMinds is a cost-effective way to improve global wellbeing, and is a particularly good fit for donors who value improving lives relative to saving them. StrongMinds is attempting to raise $19 million over the next two years to scale their services and launch an RCT.

For donors particularly focused on saving lives, see AMF below.

1.2 AMF antimalarial bednets

The Against Malaria Foundation (AMF) funds, and helps coordinate, the distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) to help prevent malaria across the world. We have added the Against Malaria Foundation as our second top charity this year because the decline in the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds makes the two more comparable.

Philosophical factors – the choice of where to place the neutral point and the badness of death – strongly influences the estimated impact of AMF, and reasonable people will hold different views. We do not take a stance about which view is correct, and there has been very little study of these issues. For more detail, see our report (Plant et al., 2022). We also made an online app that you can use to examine the cost-effectiveness of AMF under the philosophical views we described there.

LLINs can save and improve the quality of lives. We estimate their life-improving benefit from increased income is 4 WELLBYs, and their life-improving benefit from averting grief is 7.26 WELLBYs. For each life saved through AMF, we estimate the life-saving benefit ranges from 0-247 WELLBYs, depending on the philosophical view.

Based on GiveWell’s cost figures for AMF (e.g., it costs $3 to provide a bednet to one child), we estimate AMF will produce 7 WELLBYs per $1,000 donated (1x GiveDirectly) under philosophical views most favourable to improving lives but will produce up to 90 WELLBYs per $1,000 donated (11x GiveDirectly) under views most favourable to saving lives. We’re still considering how different philosophical approaches to handling moral uncertainty (another tricky issue) may be illuminating here.

We think that the evidence supporting the effect of AMF is of moderate quality because the evidence for the life-saving effects is high quality (RCTs = 23, Pryce et al.. 2018). But the evidence of malaria prevention’s life-improving effects are based on income, not subjective wellbeing, and are less generalisable to the context of bednets[8].

Our analysis is of moderate-depth. We believe that we have included most of the available evidence, but we spent limited time and our analyses rely on a number of shallow estimates. We ultimately rely on GiveWell’s analysis that AMF is a top (life-saving) charity; what we’ve done is taken GiveWell’s estimates and reanalysed its cost-effectiveness in our preferred framework, WELLBYs.

We think AMF is a good option for donors who highly value saving lives. GiveWell estimated that AMF could absorb $33.2 million in 2023, and AMF reports they could absorb $300 million. However, if one particularly values saving lives, they might also consider other GiveWell recommended life-saving charities like Helen Keller International or New Incentives.

2. Promising charities

Promising charities are well-evidenced opportunities that appear cost-effective, but we need to complete further work before we can recommend them.

2.1 Friendship Bench psychotherapy

Friendship Bench is an NGO that treats people for depression with individual, face to face, problem-solving therapy (PST), primarily in Zimbabwe and through community health workers. In 2022, they report at least 94,178 individuals received at least one session of therapy through their programmes (Friendship Bench Annual Report, 2022).

We estimate that Friendship Bench has a total effect of 1.34 WELLBYs (this includes the effect on the recipient and spillover effects on household members)[9]. We currently estimate Friendship Bench has a cost of $21 per person treated (Friendship Bench Annual Report, 2022)[10]. Overall, for the whole household the cost-effectiveness of Friendship Bench is $17 per WELLBY, or 58 (95% CI: 27, 151) WELLBYs per $1,000 spent. This is 7.0x times more cost-effective than GiveDirectly[11]. The higher cost-effectiveness than StrongMinds is driven by its lower cost, which may be due to its delivery through volunteers and having its staff based in Zimbabwe

As we said in the StrongMinds section, we think the quality of evidence supporting the effect of psychotherapy interventions is of moderate quality.

We view the depth of our analysis of psychotherapy and Friendship Bench as ‘moderate’. We believe that we have reviewed most of the available evidence. While Friendship Bench seems more cost-effective than StrongMinds, we view our current analysis as somewhat tentative and are in the early stage of our process to thoroughly understand Friendship Bench’s programme, track record, and future projects.

3. Non-recommended charities

Non-recommended charities are those which we’ve rigorously evaluated but the current evidence suggests these are not the most cost-effective funding opportunities available for improving people’s subjective wellbeing. They may be more cost-effective on a non-subjective wellbeing framework.

3.1 GiveDirectly cash transfers

GiveDirectly is a non-profit that provides cash transfers to people living in poverty. Its primary focus is in sub-Saharan Africa. We have reviewed GiveDirectly in depth (McGuire & Plant, 2021a; McGuire & Plant, 2021d; McGuire et al., 2022a; McGuire et al., 2022b). Our model suggests that donating $1,000 to GiveDirectly would result in 7.8 WELLBYs for the other household members. The total cost-effectiveness of GiveDirectly is $122 per WELLBY. Or 8 WELLBYs per $1000 donated to GiveDirectly. See our analysis for more details.

We think the evidence supporting the effect of GiveDirectly is of very high quality because there are at least 5 GiveDirectly-specific RCTs and a large general evidence base that shows no clear signs of publication bias. However, we estimate that its programme is several times less cost-effective at increasing wellbeing than our top charities, so it is not one of our top recommended charities to donate to. However, it could be a good fit for donors who: value very evidenced-based or uncomplicated interventions, need to move more funds than our top charities can absorb, or particularly value autonomy (this is not to say our top charities are not autonomy-enhancing, but arguably the case for cash is stronger regarding autonomy).

3.2 Deworming charities

Parasitic infections from worms affect around a billion people in mostly LMICs and cause a range of health problems (Else et al., 2020; WHO, 2011). The case for deworming is that it is very cheap (less than $1 per year of treatment per person) and there is suggestive evidence it might have large effects on later income (Hamory et al., 2021).

However, the evidence of the long-term impacts of deworming comes primarily from one study, the Kenyan Life Panel Survey (Baird et al., 2016; Hamory et al., 2021). Using this large data set, we conducted the first analysis of the impact of deworming on subjective wellbeing that we know of (Dupret et al., 2022). Therefore, we are relying on only one study with about ~5,200 respondents. Furthermore, the rest of the evidence base for deworming also has many non-significant findings and has led to many debates (Taylor-Robinson et al., 2019; Welch et al., 2019). Therefore, the strength of the evidence is weak.

We find a very small and statistically non-significant effect of deworming on happiness. It is not even clear how to take the effects at face value (see Dupret et al., 2022, for more detail). Because the effect is so small and uncertain, and the data come from a single study, we do not make recommendations for deworming charities at this time.

Speculative evaluations

In 2023, we explored new causes, interventions, and charities to improve wellbeing in the world. Some of this work will not be published until 2024, but we think it is worth presenting our current progress so donors and other researchers are aware of our work on these topics. In general, the evidence we’ve collected is weaker, and our forthcoming reports are shallower. We encourage readers who are interested in any of these topics to reach out to us directly for further details on these evaluations (hello@happierlivesinstitute.org).

4. Promising bets based on speculative evaluations

There are four areas that we think could be more cost-effective than our well-evidenced opportunities:

- advocacy to reduce lead exposure (McGuire et al., 2023b)

- protein supplementation to improve child development (report forthcoming)

- parenting interventions to improve child development (report forthcoming)

- community interventions to reduce gender-based violence (report forthcoming)

We don’t recommend these yet, but think they are promising and plan to look into them more.

4.1 Lead Exposure

Lead, a heavy metal that is toxic to humans (WHO, 2021), is still a common ingredient in many household items in LMICs such as paint, spices, cookware, and cosmetics. The Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP) is a charity that lobbies governments in LMICs to regulate lead in paint[12]. This prevents future cases of children being exposed to lead in paint. We think they have an exceptional track record at changing laws, regulations, and enforcement around lead paint[13]. We estimate, in a rough back of the envelope calculation (BOTEC) that $1,000 donated to LEEP would produce 872 WELLBYs, which is presently 107 times as cost-effective as GiveDirectly (McGuire et al., 2023b)[14]. The strength of the evidence we found is very weak (based on two cohort studies in high income countries). The depth of our analysis is shallow and involves a considerable degree of guesswork.

This is our top opportunity amongst the more speculative options we’ve evaluated. We recommend funding research to increase our confidence in this finding because we think this could plausibly be a top charity recommendation in future years[15]. However, donors with a higher tolerance of uncertainty might think this is a good opportunity now.

Note that we must declare a conflict of interest given that Clare Donaldson was previously the co-director of HLI but now works for LEEP.

4.2 Protein supplementation

Nutrition plays an important role in development, and undernourishment remains a wide scale problem throughout many regions. We estimate that protein supplementation during the first three years of life has a 2 to 16 WELLBY effect on subjective wellbeing[16]. We expect adding protein supplementation to a child’s diet, for the first three years of life, will cost between $20 and $120 per treatment. Altogether, this would imply energy rich protein supplementation is between 15 to 150 WELLBYs per $1,000 (2 to 15x GiveDirectly)[17]. The direct evidence for the wellbeing effect of protein supplementation during the first two years of life is weak (1 RCT, n = 1,249) and the depth of our analysis was very shallow.

The closest to actionable funding opportunity we’ve found is for Partners in Health Haiti and their partner organisation Zamni Lasante which operate malnutrition clinics that provide Nourimanba, a peanut-based, vitamin- and mineral-rich supplement. However, it is unclear whether the malnutrition programme can be funded directly[18], so we primarily recommend further research.

4.3 Parenting

Parenting interventions try to mitigate the developmental difficulties concurrent with poverty through improved caregiving, including stimulating play, reading, appropriate discipline, avoiding maltreatment, and improving parental mental health (Jeong et al., 2021). We speculatively estimate that interventions to improve parenting have a total household benefit of 8.75 WELLBYs[19]. Based on expenses of 7 different programmes, we think it costs $150 (between $8 and $800) per treatment. Overall, we estimate that a parenting programme could produce up to 58 WELLBYs per $1000 (i.e., 7x GiveDirectly). The quality of directly relevant evidence is very weak, the quality of the general evidence is weak, and the depth of our analysis was very shallow. We primarily recommend funding further research on parenting interventions, as it is unclear how promising the current direct impact opportunities are[20].

4.4 Violence against women and children

Sardinha et al. (2022; also see the WHO’s map) estimated than in the past year, prevalence of physical or sexual violence against women was 20% in Africa. We identified couples interventions, parenting interventions, and community interventions as potentially cost-effective ways to address violence against women and girls (VAWG) based on research by What Works (Kerr-Wilson et al., 2020)[21]. We found 10 effect sizes from 7 cluster randomised control trials (n = 9,222) based on these interventions. We estimate costs of the interventions reviewed ranged from $4 to $1300 per participant reached. Overall, we think that community interventions to change gender norms and reduce gender-based violence could be between 20 and 150 WELLBYs per $1,000 (3x-20x more cost-effective than GiveDirectly)[22]. The evidence is weak-to-moderate, which is better than for the other interventions we’ve reviewed in this section.

The best opportunity we have found so far is to fund Raising Voices, an organisation who trains others to implement the SASA! Approach, a community intervention[23]. This is a funding opportunity that Bansal (2023) has also recommended, but we haven’t yet looked at it closely. However, we primarily recommend funding further research on the effectiveness of interventions to reduce VAWG.

4.5 Pain alleviation

We explored the relationship between pain and wellbeing in two reports (Sharma et al., 2020; Dupret et al., 2023). These concepts seem tightly related. Our BOTECs suggest that improving access for opioids in LMICs and providing treatments for chronic pain might be promising (up to 100x as cost-effective as GiveDirectly). However, there is still fundamental research to perform, which we think could be relatively expensive, and we haven’t investigated potential charities[24] to fund.

5. Less promising interventions

There are some areas we looked into but found were less promising. This is primarily because they have limited available or easily attainable evidence, but also because they appear to have relatively low cost-effectiveness or no actionable funding opportunities. We share these as a point of comparison: we expect donors will want to know about ‘misses’ as well as ‘hits’.

5.1 Increasing immigration

In our cause exploration report on immigration, (McGuire et al., 2023a), we present a cautious case against supporting increased immigration. The evidence for the wellbeing effects of immigration is mostly correlational. Despite that, we’re fairly confident that immigration from low wellbeing to high wellbeing countries has large benefits for immigrants. We’re concerned but uncertain about the risks of backlash, where efforts to increase immigration now could prevent more immigration later, or lose allies for other causes.

When we conducted BOTECs of possible interventions to increase immigration. The most promising intervention, policy advocacy – which tends to be far more speculative than direct interventions – only came back as 11 times more cost-effective than GiveDirectly cash transfers. We’re inclined towards treating these as upper-bound estimates.

However, we’re interested in evaluating Malengo, an organisation which encourages educational immigration, primarily from Uganda to Germany, once they collect further causal evidence of their impact.

5.2 Housing improvements

Housing is an important need for humans; hence, we would expect that it has a large impact on wellbeing. However, the evidence on flooring and housing improvements in LMICs effect on subjective wellbeing is weak to moderate (1 quasi-experiment of flooring n = 2,742, one study of 3 lotteries for building tiny houses in slums, n = 2,203). Flooring upgrades appear more cost-effective than complete housing upgrades, and cost around $300 per treatment. However, these do not appear particularly promising since we think 30 WELLBYs per $1,000 is an optimistic estimate. EarthEnable is a charity-for-profit hybrid where the charity oversees the operation of two for-profits in Uganda and Rwanda that build earthen floors that are purportedly waterproof and durable.

5.3 Fistula prevention and repair

Obstetric fistula is an abnormal opening between a woman’s genital tract and her urinary tract or rectum (WHO, 2018). Fistula repair surgery is 86% successful and costs ~$1,400 per treatment, although this is based on weak evidence , so is correspondingly uncertain. We expected that surgery to repair fistulas could strongly improve the wellbeing of women in LMICs. We estimate that a fistula repair surgery improves wellbeing by 25-60 WELLBYs per $1,000 spent. However, this calculation is based on multiple assumptions and guesses. Furthermore, the core evidence base involves pre-post studies; hence, it doesn’t give us causal information about the impact of the surgeries.

We know of two charities that provide fistula repair surgeries. The Fistula Foundation (which has previously been evaluated by GiveWell, 2021. And the Catherine Hamlin Fistula Foundation. But currently we do not make recommendations for fistula repair charities.

5.4 Treating alcohol use, thought, or neurological disorders

We tried to find if there were any promising opportunities to treat mental health or neurological issues that weren’t mood disorders. We looked into interventions and organisations treating alcohol use, drug use, thought disorders (like psychosis or schizophrenia), and epilepsy. We deprioritized this because the evidence is overall weak and there appear to be few relevant funding opportunities or avenues for cheap but valuable research.

Alcohol use

We think an optimistic estimate of the evidenced cost-effectiveness of interventions to address alcohol use is around 3x GiveDirectly cash transfers, based 8 RCTs with 1,856 participants that involved brief counselling interventions that lasted an hour on average[25].

After an extensive search of the Mental Health Innovation Network (MHIN, we found no organisations specifically focused on reducing harm from alcohol abuse. Sangath may have or know of opportunities to fund harmful alcohol use reduction in India, but related researchers have not responded to our inquiries.

From this, we concluded that the evidence is currently too weak, the speculative cost-effectiveness too low, and the funding opportunities too inactionable to support further investigation.

Drug use

We only found evidence for psychological treatments of substance use (4 RCTs, n = 1,126). The effects on depression for these was a 0.48 SD (95% CI: 0.18, 0.78) decrease in depression symptoms. The interventions had a considerably higher time spent in treatment than the alcohol interventions (35 hours spent in treatment versus around 1 hour in total), which may explain the larger effect size. We expect the costs and duration to be similar to addressing alcohol use, implying a low cost-effectiveness for the weak evidence. We also found no organisation focusing on addressing substance use through small scale interventions in LMICs.

Thought disorders

The only evidence in LMICs we found with wellbeing outcomes was 3 RCTs (0.58 SDs, n = 208) of family interventions to improve the quality of care families provide to sufferers from schizophrenia.

These interventions appear to cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per person ($3,823, Ghadiri et al., 2015; $627, Gureje et al., 2020). This leads us towards believing that the cost-effectiveness of treating thought disorders in LMICs is relatively low[26].

We found some organisations focusing on treating thought disorders, but none focusing on using family based interventions. Altogether, because of low-cost effectiveness and the weakness of evidence, we have not prioritised further research.

Epilepsy

Anti-epileptic drugs, the primary treatment for epilepsy, appeared to be 50% at stopping seizures 2 years after initiation (Jost et al., 2018). But none of these studies reported mental health or subjective wellbeing measures appeared as primary or secondary outcomes in the 31 studies it meta-analysed. This suggests that there does not appear much direct wellbeing evidence on treating epilepsy in LMICs, and thus we deprioritized evaluating treating epilepsy in LMICs as an intervention.

Research priorities

In looking for the most cost-effective opportunities to increase wellbeing, we also discover what the gaps in the research landscape are. Here, we highlight where new evidence, or analysis of the existing evidence, would be particularly informative for determining the priorities. We may be able to conduct this research ourselves, or find partners who will. If you are interested in funding any of these research opportunities, please contact us at hello@happierlivesinstitute.org.

Malaria prevention

Our evaluation of antimalarial bednets lacks data that measures wellbeing directly. However, we have seen preliminary research indicating that malaria prevention may have life long benefits for mental health. We think there is an opportunity to fund research that builds on this work for around $20,000-$60,000.

We think the value of research here is relatively high as we think there’s a good chance further research could qualitatively change our recommendations if it turned out malaria prevention was relatively more effective at improving quality of life.

Further research about understanding how to make reasonable trade-offs between quality and quantity of life would be very helpful here too, but we think is very difficult to do. Two options we are considering are:

- More careful survey work to understand where people place the neutral point on subjective wellbeing scales in LMICs.

- Work that allows for implementing moral uncertainty practically, such as cases like malaria prevention, where the estimated benefits depend on moral considerations.

Psychotherapy

We still expect further research into household spillovers to be highly informative, but relatively expensive since it would involve primary RCT work (costing between $50,000 to $500,000).

There remains surprisingly little research into this area (3 RCTs in LMICs), despite the massive role this parameter plays in our estimate of the effectiveness of psychotherapy. There has been no study that deliberately tries to estimate the household spillover effect on multiple household members (where we’ve found this data, it has been a secondary outcome).

Estimating household spillovers, while more complicated and expensive than surveying only direct recipients, seems like a cost-effective manner of improving our knowledge of an extremely important area. Spillovers can represent the vast majority of the estimated effect (a case we made in Section 6 of McGuire et al., 2022b, and in our new report, McGuire et al. 2023c). Therefore, measuring spillovers seems like a relatively cheap extension of present RCTs when considering the potential information gained. It would involve randomly surveying different members of the household when the direct recipient is surveyed.

Cash transfers

Since the quality of the existing evidence is so high, we think further research has a relatively low value of information. If further research was to be pursued about cash transfers, we would be most interested to investigate the following questions:

- What are the long term wellbeing effects of receiving a cash transfer in childhood?

- How much does adding the mortality reduction effects of cash transfers (Richterman et al. 2023) improve its cost-effectiveness?

- Do different values of cash transfers lead to different levels of cost-effectiveness due to the diminishing marginal utility of income?

Deworming

We do not know of any easily actionable research opportunities for deworming. The question we would most like to answer about deworming, if resources were not a constraint, is whether it has measurable short term (0 to 2 year after receipt) benefits to wellbeing.

Research priorities for promising bets

Advocacy to reduce lead exposure

We are especially excited about a possible opportunity to fund the first causal study relating early life lead exposure to later in life mental wellbeing. This work would be in collaboration with a team of economists who’ve published on the causal relationship between lead exposure and health outcomes.

Protein supplementation

We believe there are several promising opportunities to encourage research related to the wellbeing effects of protein supplementation with small grants. The research we’re more interested in encouraging would be to study existing (hitherto un-analysed) data on (1) the long term mental health effects of two nutrition trials in india[27], and (2) the effects of childhood exposure to the 1983 famine in Ghana[28].

Parenting interventions

We think there are several research opportunities here worth funding, but we think that these research opportunities may have more moderate cost-informativeness compared to the opportunities for lead exposure and protein supplementation.

These opportunities, in order of our view of their importance are:

- Fund the team of Islam et al. (2022) to follow-up their BRAC Bangladesh study which looks at the effects on mother and children’s mental health and subjective wellbeing.

- Provide a small grant to encourage the replication and expansion of Yang (2021) to include wellbeing variables.

- Replicate and update meta-analyses studying the wellbeing effects of parenting programmes.

Preventing violence against women and girls

We think there are several research opportunities here worth funding, but we think that these research opportunities may have more moderate cost-informativeness.

A small grant would allow us or a partner to replicate and update meta-analyses of the effects of these interventions on rates of violence in order to model these over time and convert their effects to effects on wellbeing.

Ideally, we’d welcome more studies of the effects of interventions tackling VAWG on wellbeing measures, over longer periods of follow-up, and with measures of household spillovers. This could strongly improve understanding of these interventions. However, who to fund to make this happen is unclear.

Pain alleviation

The research opportunities here are more fundamental, and likely more expensive and less cost-effective than other areas. Hence, these are likely relatively less promising than many other opportunities. We’d be excited to see research on:

- Whether subjective wellbeing measures can assess wellbeing for those in extreme pain, the potential household spillovers of being in pain and pain treatments.

- Systematically collecting case studies of palliative care reform to better estimate the likelihood of advocacy success (see Sharma et al., 2020 or OPIS for example).

- Understanding the causal effect of providing pain relief on pain and wellbeing levels in palliative care centres in LMICs.

Research priorities for less promising interventions

For immigration, we’re interested in evaluating Malengo, an organisation which encourages educational immigration, primarily from Uganda to Germany, once they collect further causal evidence of their impact. We have not come across any particularly promising research opportunities, for housing improvements, fistula prevention, or treating non-mood mental or neurological conditions. If we were to do more research in these areas, we would try to collect more causal effects, and details of implementers for these interventions.

Conclusion

Our current recommendations reflect the opportunities for improving wellbeing that we have evaluated so far. It is likely that there are other highly impactful organisations we have not yet investigated. We aim to continually expand our research and look at further causes, interventions, and charities. Our recommendations may change over time as we discover more cost-effective opportunities or as new data is published concerning our ‘top charities’. We welcome feedback on our methodology and suggestions for other interventions and organisations to consider. If you have feedback, please contact us at hello@happierlives.org.

- ^

We follow a three-stage process to identify the most effective charities. (1) We find global problems that are important, solvable, and neglected. (2) We identify interventions that alleviate those problems and assess their cost-effectiveness. (3) We evaluate the best charities we can find that deliver those interventions.

- ^

One WELLBY is equivalent to moving someone up one point on a standard zero to ten wellbeing scale for a year (e.g. from 6/10 to 7/10). We didn’t invent this (see Brazier & Tsuchiya, 2015; Layard & Oparina, 2021) and the UK Treasury (2021) recently approved the same approach.

- ^

Notably, comparing the cost-effectiveness of these charities is difficult, because the benefit of StrongMinds is that it improves lives, while AMF primarily saves lives. Comparing the value of improving lives and saving lives involves addressing difficult philosophical issues. Due to this complexity, we noted last year that AMF may be a good option for some donors, but we did not recommend it as a top charity.

- ^

We don’t currently use a ‘bar’ to judge cost-effectiveness: we simply recommend the best things we know of. Though, we often estimate how cost-effective interventions are relative to cash transfers as a convenient point of comparison. Other evaluators may also use cash transfers as a benchmark, but unless they use the WELLBY framework, the cost-effectiveness ratios would not be directly comparable.

- ^

They represent the upper and lower bound of cost-effectiveness for different philosophical views (not 95% confidence intervals as we haven’t represented any statistical uncertainty for AMF). Think of them as representing moral uncertainty, rather than empirical uncertainty. The upper bound represents the assumptions most generous to extending lives and the lower bound represents those most generous to improving lives. The assumptions depend on the neutral point and one’s philosophical view of the badness of death (see Plant et al., 2022, for more detail). These views are summarised as: Deprivationism (the badness of death consists of the wellbeing you would have had if you’d lived longer); Time-relative interest account (TRIA; the badness of death for the individual depends on how ‘connected’ they are to their possible future self. Under this view, lives saved at different ages are assigned different weights); Epicureanism (death is not bad for those who die – this has one value because the neutral point doesn’t affect it).

- ^

StrongMinds intervention characteristics (delivered by non-experts, to groups, with 6 sessions), predicts that StrongMinds has a lower effect (1.53 WELLBYs) than the average therapy (2.69 WELLBYs). We also expect the forthcoming StrongMinds-specific RCT will report a much smaller than average effect. When we combine this with the general evidence, this reduces the meta-analytic predicted effect of 1.53 WELLBYs to 1.35 WELLBYs.

- ^

If we only consider the effects on the direct recipient, the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds would become much more favourable compared to GiveDirectly (10x GiveDirectly), but much less so to AMF. We also find that taking all obvious unfavourable or favourable StrongMinds modelling choices would result in a cost-effectiveness of 7 (0.9x GiveDirectly) or 187 (22.8x GiveDirectly) WELLBYs per $1,000 donated.

- ^

The evidence is based on natural experiments studying historical episodes of malaria eradication 50-100 years ago, so we’re very uncertain if the effects are generalisable to present malaria-suppression efforts.

- ^

We estimate that Friendship Bench benefits the individual recipient of their intervention by 0.91 WELLBYs. This is less than the 1.35 WELLBYs we estimate for StrongMinds or the 2.69 WELLBYs we estimate for the average psychotherapy intervention.This is because Friendship Bench intervention characteristics (delivered by non-experts, with an average of 2 sessions), predicts that Friendship Bench has a lower effect (0.82 WELLBYs) than the average psychotherapy (2.69 WELLBYs). The difference is starker between Friendship Bench and the general evidence (than for StrongMinds) because Friendship Bench delivers fewer sessions in practice. However, the charity-specific evidence (three RCTs, participants = 1,115) suggests a larger than predicted effect (2.36 WELLBYs). Combining the Friendship-Bench-specific data with the general evidence results in a slight upwards adjustment to our estimate of its effects – from 0.82 WELLBYs to 0.91 WELLBYs. Like StrongMinds, we also combine the general psychotherapy evidence and the Friendship-Bench-specific evidence in a formal Bayesian manner (see McGuire et al., 2023c, for more detail).

- ^

These figures are not reported publicly, so it is difficult to independently verify them. However, USAID (2022) has provided Friendship Bench with a substantial grant ($1.3 million), where they mention it costs $18 per person to deliver the full programme. Furthermore, Friendship Bench provided us with an itemised breakdown of costs where items are easy to sense-check, and they shared information about their low dosage which suggests a sub-optimal implementation, thereby improving their credibility in our eyes.

- ^

If we only compared the cost-effectiveness of the recipient effects (i.e., not including household spillovers), Friendship Bench would be 21x more cost-effective than GiveDirectly. We found that if one made all of the least or most favourable analytical choices towards Friendship Bench it would result in a cost-effectiveness of 8 (0.9x GiveDirectly) or 407 WELLBYs (49.7x GiveDirectly) per $1,000 donated.

- ^

We haven’t evaluated Pure Earth, another organisation that works at reducing lead exposure internationally, but we think they could have similar impact and cost-effectiveness to LEEP. They work on many different projects such as measuring lead levels and advocacy (e.g., they recently claim to have had an extremely successful campaign to remove lead from Tumeric in Bangladesh). Other evaluators and grantmakers have also supported Pure Earth (GiveWell, Open Philanthropy).

- ^

For a total expenditure of around $1.2 million since their inception, they have received government commitments from 10 countries to implement or enforce regulation against leaded paint, initiated programs in 18 countries and have a total of 5 countries where the majority of lead paint production appears to be switching to lead free paint (LEEP, 2023).

- ^

This is based on a speculative estimate that an additional microgram of lead per deciliter of blood during ten years in childhood, leads to a total lifelong (62 years) loss of 1.5 WELLBYs, and a larger overall 3.8 WELLBYs loss when we include some guesses about household spillovers. For context, over half of children in the world have blood lead levels of 5 micrograms per deciliter (μg/dL) or more (and over 10% have over 10 or more; Pure Earth & UNICEF, 2020; OWID, 2023). Furthermore, we’ve seen some preliminary research that suggests a stronger causal relationship between lead exposure and later in life wellbeing outcomes.

- ^

Other evaluators and grantmakers appear to agree that LEEP is a promising charity (Rethink Priorities, Open Philanthropy, Founders Pledge). A recent presentation and conversations with those working in the field of reducing lead exposure indicate that the space could still productively absorb more funding.

- ^

This back of the envelope calculation is based on two sources. First, we used the results from a 50 year follow-up of an RCT of 8 years of energy rich protein supplementation (DiGirolamo et al., 2022, n = 1,249). Second, we anchored this estimate between two other bounds: the causal very long term wellbeing effect of exposure to famines (-0.15 SDs, 6 natural experimental studies of 2 famines, n = 37,887) and fasting during pregnancy (-0.06 SDs, 3 natural experiments, n = 124,080).

- ^

This range depends on whether we apply an arbitrary 70% or 90% discount to the effect of direct evidence and use the upper or lower bound cost estimate.

- ^

Many organisations address malnutrition during the first 1,000 days of life (World Food Program, Save the Children, Phase Worldwide and Doctors With Africa), but it’s unclear what the content or cost of nutritional interventions are. Edesia produces a primarily peanut based food to target malnutrition, but their financials show that in 2021 they ended the year $7million richer than they started, ending up with a total of $39 million, making it questionable whether further funding would have any impact.

- ^

The direct evidence of parenting interventions on affected children’s mental health and subjective wellbeing as adults is weak (d = 0.28, RCTs = 2, n = 426). But we also consider three other sources of evidence. (1) The very long term wellbeing effects of early childhood development programmes in HICs (d = 0.15, 4 programmes, 7 studies, n = 3,403). (2) The short term effects of parenting programmes on adolescents in LMICs (d = 0.2, RCTs = 9, n = 2,530). (3) The short (d = 0.09, RCTs = 18) and long term (d = 0.24, RCT = 1) effects of parenting programmes on mother’s mental health.

- ^

One organisation we’ve considered that we think is implementing a similar programme to the ones we estimate the impact for. This is BRAC’s parenting support programme in Bangladesh. Islam et al. (2022), describes the intervention and the short run effects of the intervention. The intervention involved psychoeducation, parenting support for mothers, and engagement in culturally appropriate play activities during treatment sessions delivered by trained volunteer community peers. The treatment was provided weekly for a year through 44 hourly sessions.

There are two programmes from Save the Children (described in Justino et al. 2022 and Chinen et al. 2014) that we have also considered which are incredibly cheap ($2 to $7), but they differ more in content from the programmes presented above, and we haven’t reviewed direct evidence for them. However, we think further comparison of the content and quality of these programmes is worthwhile given their low costs.

- ^

We didn’t include economic or psychotherapy-based interventions here because we wanted to find something sufficiently distinct from our previous recommendation and research.

- ^

There seems to be high heterogeneity between and within these different interventions. This complicates the evaluative task because the implementation details of interventions targeting VAWG play an important role (Jewkes et al., 2021). Conversations with experts from the research consortium on reducing VAWG seem to support this notion.

- ^

We do not have specific subjective wellbeing data for SASA! (although its effects on violence are well documented, Abramsky et al. 2014).

- ^

A few we are aware of but have not evaluated are Douleur sans frontière, Pallium India, and Organisation for the Prevention of Intense Suffering (OPIS).

- ^

Most of these interventions were ‘motivational interviewing’, a brief (1-4 sessions) counselling intervention often deployed in primary care settings which aims to guide patients to provide their own reasons for wishing to change harmful behaviours, and providing support (Rollnick et al., 2010). We meta-analysed these results and found that reducing alcohol abuse with brief counselling interventions has an initial effect of 0.33 (95% CI: -0.10, 0.76) that decayed -0.02 SDs (95% CI: -0.07 0.03) per month, implying a duration of 1.2 years. Nadkarni et al. (2017) finds an average cost of $33, naively implying a cost-effectiveness around 3x GiveDirectly cash transfers.

- ^

This assessment seems to be in line with Patel et al. (2016) which suggests that treating schizophrenia is much less cost-effective from a DALY perspective compared to treating epilepsy, and alcohol or mood disorders (i.e., $236 - $407 per DALY for alcohol compared to $1,427 - $8,390 for treating schizophrenia).

- ^

First, Nandi et al. (2018, n = 1,360) follows a controlled trial of a nutritional intervention in India after 20-25 years and contains, but did not study, the mental health outcomes. We’ve received some indication that the authors of this study may be interested in analysing the mental health effects of this study. We think a small grant to facilitate this analysis could have a high value of information. Similarly, Dhamija, and Sen (2020) evaluate the long-term effects of a separate large-scale programme in India which aimed to improve nutrition and general development of children. The data they use includes, but does not analyse the likelihood of being diagnosed with a mental illness. We think a small grant could encourage more research.

- ^

We could also collect better general evidence on the adult wellbeing effects of early life exposure to nutritional shocks by extending Ampaabeng and Tan (2013). They found that cognitive ability was affected by exposure to a famine in 1983 in Ghana, and that effects were largest for those under the age of two. It seems very plausible that, using the strategy of Adhvaryu et al. (2019), whose data is publicly available, this could be expanded to find the mental health effects. Since the data is public, we recommend supporting a small grant ($1,000 to $5,000) to encourage a graduate student to write their thesis on this topic and allow HLI staff to supervise or find a supervisor through our academic network.

Thanks for the update, and making an online cost-effectiveness app!

For deprivationism, which is my prefered view on the badness of death, and your default parameters:

However, I do not think AMF is the right reference. I estimate corporate campaigns for chicken welfare, like the ones supported by The Humane League, are 1.37 k times (= 1.71*10^3/0.682*2.73/5) as cost-effective as GiveWell's top charities (one of which is AMF):

I appreciate estimating the cost-effectiveness of animal welfare interventions in terms of WELLBY/$ presents some challenges (animals cannot be surveyed). Nonetheless, corporate campaigns for chicken welfare look way more cost-effective than GiveWell's top charities based on the above, and neither StrongMinds nor Friendship Bench are clearly superior to AMF. So I do not see how StrongMinds or Friendship Bench could increase wellbeing more cost-effectively than corporate campaigns for chicken welfare.

I'm very excited by the work HLI is doing.

I'm a little confused by what psychotherapy refers to in this post, is this going by HLI's contextual definition "any form of face-to-face psychotherapy delivered to groups or by non-specialists deployed in LMICs"?

I guess not strictly related then, but I'd be interested to know if anyone is aware of cost-effectiveness analyses using WELLBYs for one-on-one traditional psychotherapy/counselling, as this is a relevant baseline for a project I'm drafting.

Hi Victor,

Our updated operationalization of psychotherapy we use in our new report (page 12) is

"For the purposes of this review, we defined psychotherapy as an intervention with a structured, face-to-face talk format, grounded in an accepted and plausible psychological theory, and delivered by someone with some level of training. We excluded interventions where psychotherapy was one of several components in a programme."

So basically this is "psychotherapy delivered to groups or individuals by anyone with some amount of training".

Does that clarify things?

Also, you should be able to use our new model to calculate the WELLBYs of 1 to 1 more traditional psychotherapy since we include studies with 1 to 1 in our model. Friendship Bench, for instance, uses that model (albeit with lay mental health workers with relatively brief training). Note that in this update our findings about group versus individual therapy has reversed and we now find 1 to 1 is more effective than group delivery (page 33). This is a bit of a puzzle since it disagrees somewhat with the broader literature, but we haven't had time to look into this further.

That's clear to me now and thank you also for the pointer on 1 to 1 effectiveness!