[Warning: Disturbing content ahead. Why talk about it? This is an ethically very serious topic and it deserves more attention. But please beware that thinking about this might be bad for one’s mental health.]

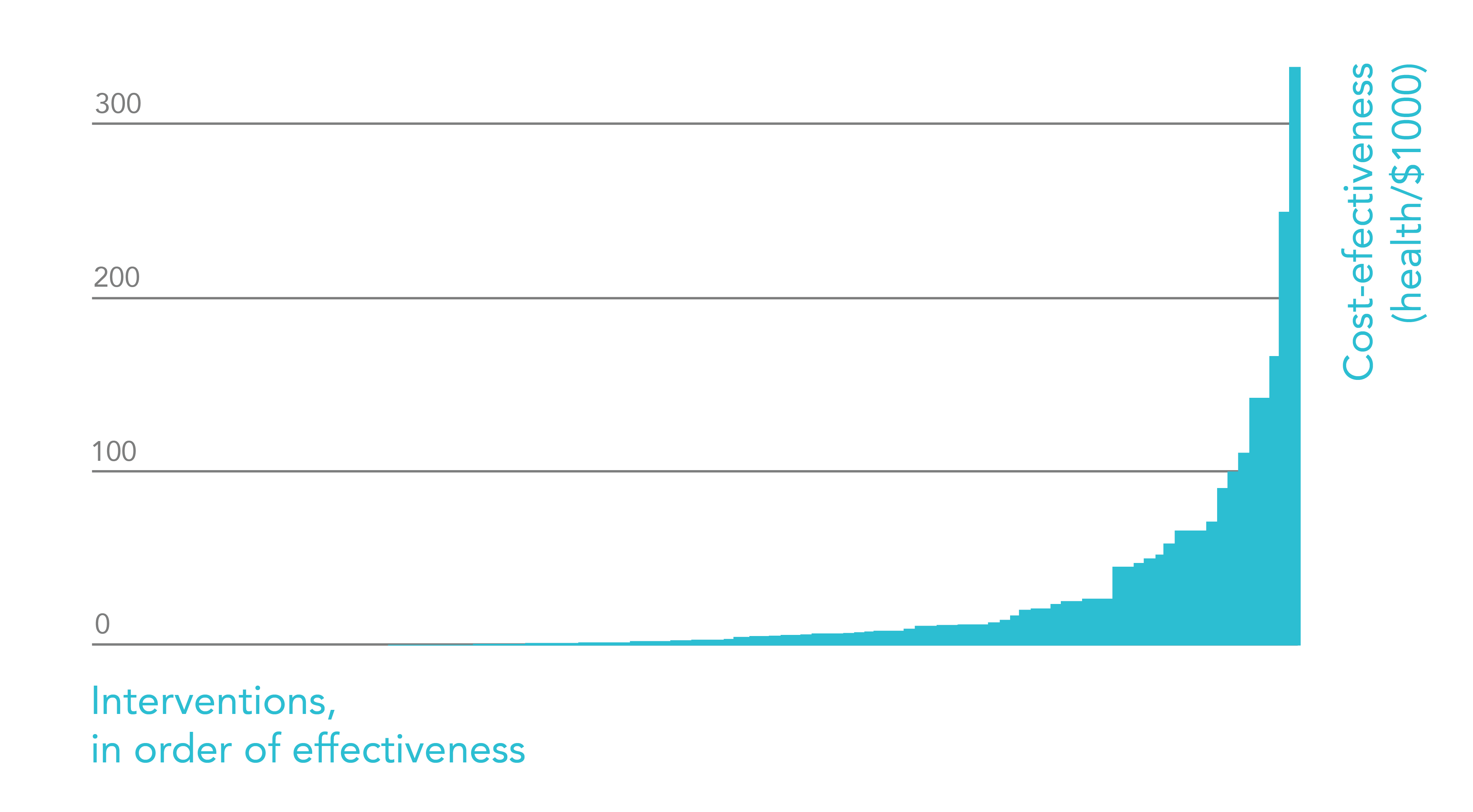

One of the key insights that shows why Effective Altruism is so important is that the positive effect on the world that results from donating to various charities follows a long-tail distribution:

Cost-effectiveness of health interventions as found in the Disease Controls Priorities Project 2. See “The moral imperative towards cost-effectiveness in global health” by Toby Ord for more explanation. [Taken from: The world’s biggest problems and why they’re not what first comes to mind]

It is for this reason why focusing on the best interventions really pays off. Where else can we expect long-tails to appear?

In Get-Out-Of-Hell-Free Necklace we discussed how introducing a new metric into the Effective Altruist ecosystem could shed light on neglected cost-effective interventions. We presented the Hell-Index:

A country’s Hell-Index could be defined as the yearly total of people-seconds in pain and suffering that are at or above 20 in the McGill Pain Index (or equivalent)*. This index captures the intuition that intense suffering can be in some ways qualitatively different and more serious than lesser suffering in a way that isn’t really captured by a linear pain scale.

In a future article we will discuss how the quality of suffering as a function of different medical and psychological conditions very likely follows a long-tail distribution. That is, some conditions such as Cluster Headaches (which affect about 1 in 1000 people worldwide) produce pain that is orders of magnitude worse than the pain experienced in other kinds of medical conditions, such as migraines (which are themselves already described as orders of magnitude worse than tension headaches). In other words, a 0-10 pain-scale is better thought of as a logarithmic compression of the true levels of pain rather than a linear scale. So concentrating on the worst conditions could really pay off for reducing suffering in bulk amounts.

Now: the long-tailed nature of suffering may extend beyond the quality of suffering, and show up also in its quantity. That is, the frequency with which people experience episodes of intense suffering, even among those who experience the same kind of suffering, is unlikely to be normally distributed.

Intuitively, one may think that how much suffering people endure on a given year follows a normal distribution. This intuition says that if the median number of hell-seconds people endure in a year is, say, 1,000, then people who are at the 90% percentile of hell-seconds experienced per year will be experiencing something like 1,500 or at most 2,000. If suffering follows a long-tail distribution, in reality the 90% percentile might be experiencing something more akin to 10,000 hell-seconds per year, the 99% percentile something akin to 100,000, and the 99.9% something akin to 1,000,000. If true, such a heavy skew of the distribution would suggest that we should concentrate our energies on addressing the problems of the people who are unlucky to be on the upper ranges, rather than be overly concerned with “the typical person”*.

Unfortunately, I come to share the bad news that suffering probably follows a very long-tail distribution:

It is generally acknowledged that Cluster Headaches are some of the most painful experiences that people endure. Having a single Cluster Headache, lasting anywhere between 15 minutes to 4 hours, is already an ethically unacceptable situation that should never happen to begin with. It is disheartening to know that 1 in 1,000 people experience such extreme pain. But the truth of the matter is yet much worse than we intuitively think…

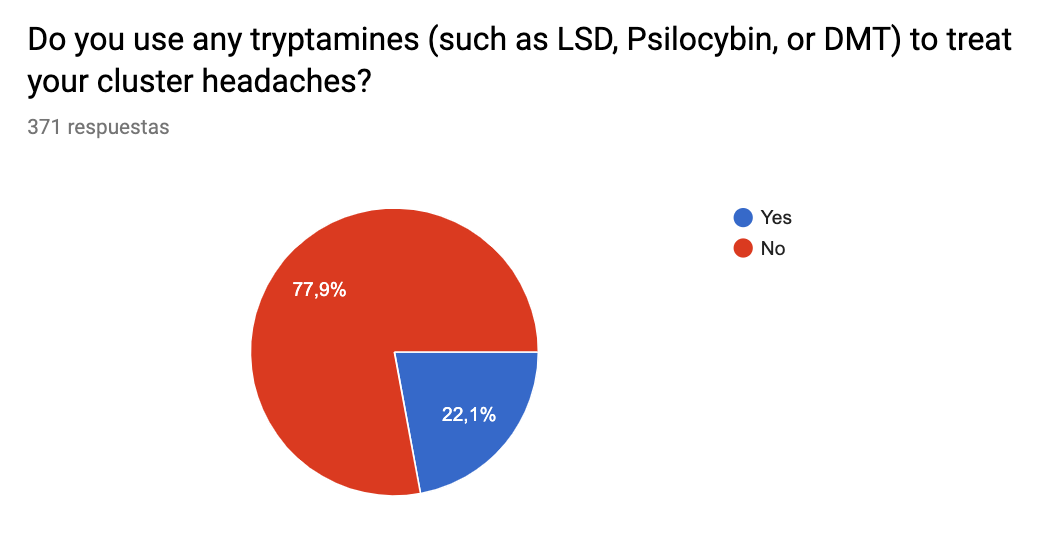

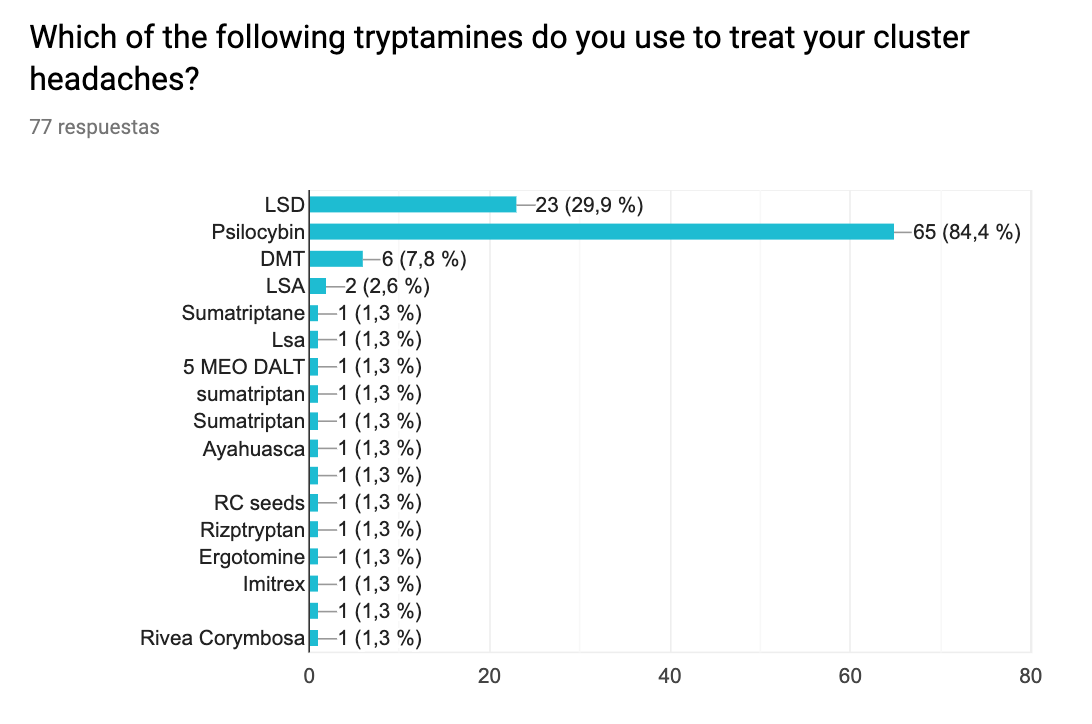

We recently analyzed a survey** of Cluster Headache patients that was conducted with the intention of determining the reasons why sufferers do or do not use psychedelics to relieve their pain. As it turns out, LSD, psilocybin, and DMT all get rid of Cluster Headaches in a majority of sufferers. Given the safety profile of these agents, it is insane to think that there are millions of people suffering needlessly from this condition who could be nearly-instantly cured with something as simple as growing and eating some magic mushrooms.

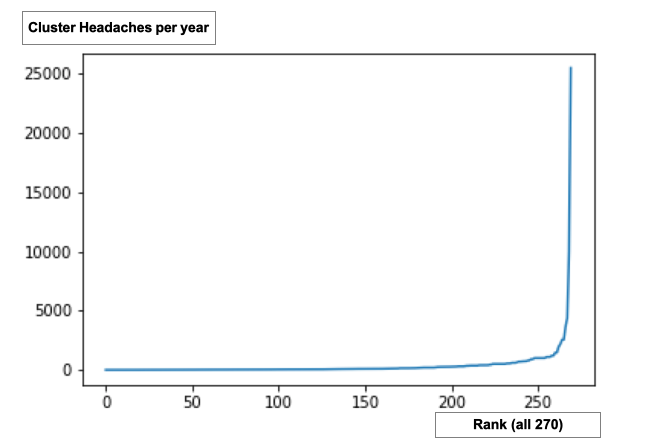

We will get back to this in more depth in later articles, but for the time being what we want to highlight is the responses to the question “About how many cluster headaches do you get in a typical year?”.

After cleaning the data***, we end up with 270 participants. We then ranked the values from smallest to largest, and visualize them:

Honestly I am a bit suspicious of the very top numbers (I do not know how you can fit 25,000 Cluster Headaches in a year, so perhaps the participant interpreted the question as “lifetime number of Cluster Headaches”). So, just to be safe, we cut the top 20 highest numbers and visualize the bottom 250 values:

This is clearly a long-tail distribution. And since many people online do claim to have 3 or more Cluster Headaches a day, I am inclined to believe this curve. To zoom in on some parts of the distribution, here are some additional histograms that focus on the lower percentiles:

(Bins of 1, responses between 1 and 10 CHs per year.)

(Bins of 1, responses between 1 and 100 CHs per year.)

(Bins of 10, responses between 1 and 1000 CHs per year.)

(Bins of 100, responses between 1 and 2000 CHs per year.)

(Bins of 10, responses between 1 and 5000 CHs per year.)

If we take the logarithm of the number of yearly Cluster Headaches, the distribution looks remarkably normal:

(Above: Natural log of the responses to the question “About how many cluster headaches do you get in a typical year?”)

Using a Shapiro-Wilk normalcy test does not rule out a Gaussian distribution (p >0.05). Although this in no way shows that that the distribution is log-normal (which would require more specialized statistical analysis), it is at least suggestive of it.

I should also point out that the distribution is really close to the 80/20 Pareto principle – we see that the top 20% of the participants contain about 83% of the CH incidents per year. Below you will find the percent of the total number of incidents accounted for by the bottom x% of the respondents:

- The bottom 10% accounts for .06% of incidents

- The bottom 20% accounts for 0.36% of incidents

- The bottom 30% accounts for .95% of incidents

- The bottom 40% accounts for 1.82% of incidents

- The bottom 50% accounts for 3.17% of incidents

- The bottom 60% accounts for 5.54% of incidents

- The bottom 70% accounts for 9.56% of incidents

- The bottom 80% accounts for 17% of incidents

- The bottom 90% accounts for 30% of incidents

- The bottom 95% accounts for 43% of incidents

Below we also include the number of yearly Cluster Headaches experiences at different percentiles:

- 10% percentile experiences 5 CH/year

- 20% percentile experiences 17 CH/year

- 30% percentile experiences 30 CH/year

- 40% percentile experiences 45 CH/year

- 50% percentile experiences 70 CH/year

- 60% percentile experiences 105 CH/year

- 70% percentile experiences 200 CH/year

- 80% percentile experiences 365 CH/year

- 90% percentile experiences 730 CH/year

- 95% percentile experiences 1095 CH/year

- 98% percentile experiences 2190 CH/year

I believe that this information is crucial to consider when assessing cost-effective interventions to help people who endure intense suffering.

Here are some additional results from the survey.

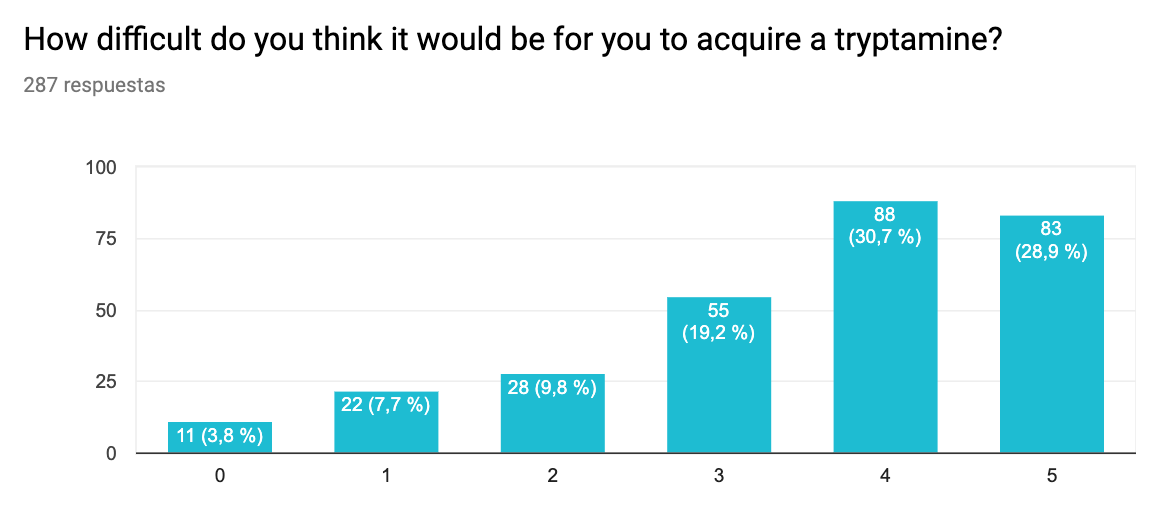

The following graphs are about the beliefs and attitudes of Cluster Headache sufferers who do not use tryptamines (LSD, psilocybin, DMT, etc.) to treat their condition:

(Difficulty getting. 0 – Extremely easy to acquire, 5 – Nearly impossible to acquire)

(Legal risk. 0 – Not concerned at all, 5 – Extremely concerned)

(Side effects. 0 – Not concerned at all, 5 – Extremely concerned)

(Social stigma. 0 – Not concerned at all, 5 – Extremely concerned)

I think it is fair to say that the survey shows that one of the biggest barriers preventing CH patients from using tryptamines to treat their condition is simply the difficulty of acquiring them. Since a number of interviews we’ve conducted have shown that even sub-hallucinogenic doses of DMT can abort cluster headaches (writeup coming soon), more education could easily address the barrier of being concerned about hallucinogenic side effects. The social stigma seems like a minor problem, and the legal implications (the hardest to change, perhaps), are a big concern to about half of the participants (ratings of 4 or 5/5). Hence the importance of passing new laws allowing people with this condition to use them without repercussions.

Do CH sufferers who do not use tryptamines think they would work?

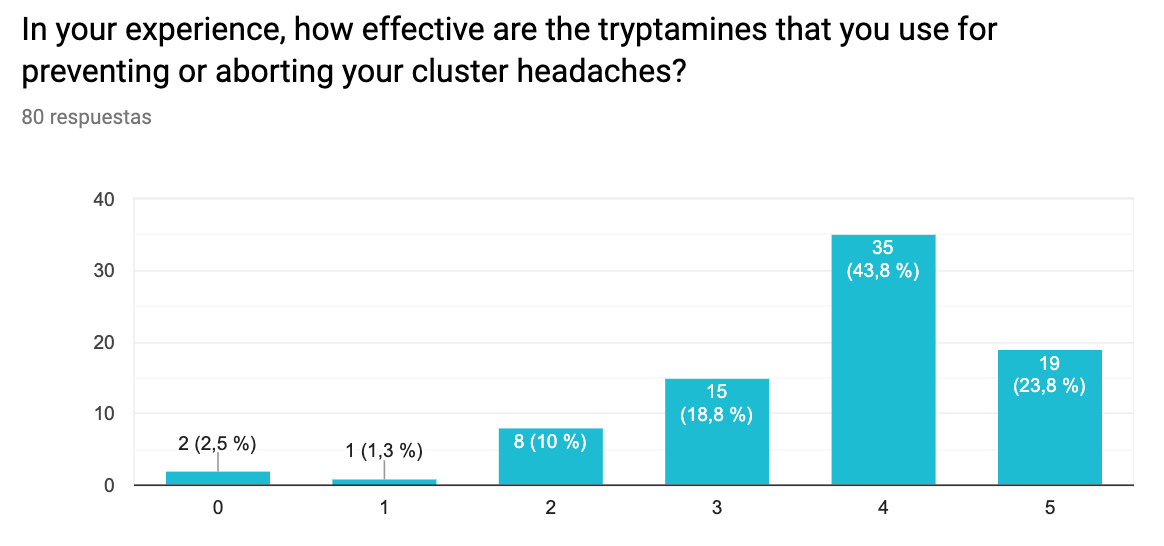

And do they work? Here is what the CH sufferers who do use them say:

If we interpret a 2 or 3 in the 0 to 5 scale as an equivalent to a “maybe”, and a 4 or 5 as a “yes” to the question “do they work?” we see a big difference between non-users' beliefs in their effectiveness and their reported effectiveness by users. 24% of people who use tryptamines to treat their CHs report that “They have completely eliminated the cluster headaches” and in total 68% mark it as either a 4 or a 5 in the scale (which we can interpret as “working” even if not “completely eliminating them”). This is compared to only 30% of non-users who believe the tryptamines would work. This large discrepancy also suggests that outreach and education could help sufferers give this approach a try.

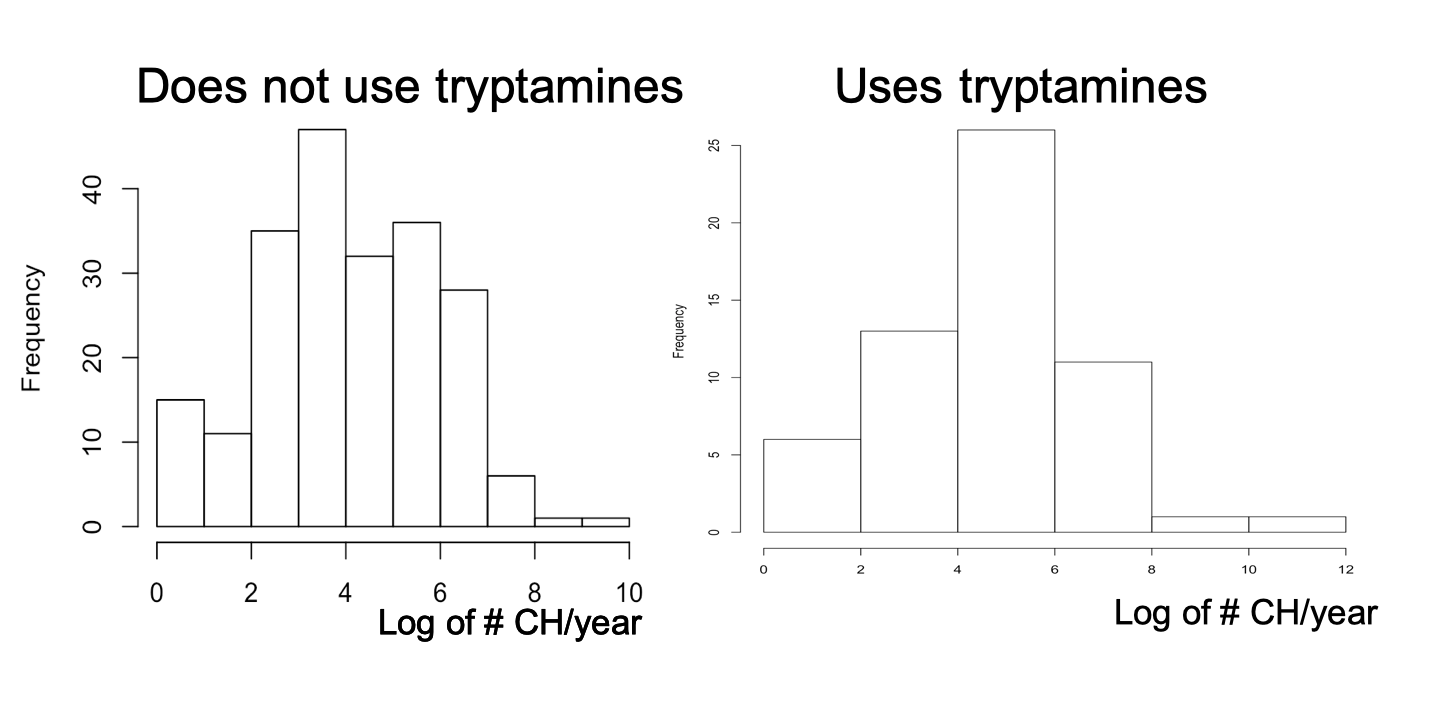

Finally, we also looked at whether the users and non-users had different number of incidents per year (reasoning that perhaps those who experience more incidents would be more desperate to try legally and socially risky treatments). We noticed that there is a very slight difference in the mean (and mean-log) for the number of CH incidents a year between the 20% of sufferers who treat their CHs with tryptamines and those who don’t. I won’t report the difference in the mean because the skew of the distribution makes such a metric deceptive, but the log-mean of yearly incidents of tryptamine users is 4.73 whereas for all the rest it is 4.10 (which reaches statistical significance of p < 0.05 based on a t-test). That said, we don’t think this is a very practically relevant difference. The distributions look roughly the same:

The similarity between these two distributions also suggests that there is a long way to go to make sure that those who are the worse off get prompt access to tryptamines.

The End.

See also https://clusterbusters.org/, which is an organization that aims to make psychedelics legally available to people who suffer from this condition. Please consider donating to them to help this very important cause. Also consider donating to MAPS which is championing the use of psychedelics for mental health applications. Finally, consider also donating to organizations that care and strategize about how to reduce intense suffering, such as: QRI, FRI, OPIS, and The Neuroethics Foundation.

*There are instrumental considerations here – if experiencing more than, say, 5,000 hell-seconds in a year is very likely to make you depressed and ineffective, then it might pay-off to also spend resources on keeping as many people as possible below that level. In particular, to be an effective Effective Altruist it pays off not to be heavily depressed and nihilistic.

**Thanks to Harlan Stewart for taking the initiative to conduct this survey. He advertised it on the Facebook groups and subreddits of Cluster Headache sufferers and got 371 responses.

***Some people provided numerical answers, which we used directly. Some other people provided ranges, in which case we used the middle point between the values provided (e.g. “200 to 300” was coded as “250”). Some people provided lower bounds, in which case we simply used such lower bound (e.g. “500+” was coded as “500”). We discarded the data of people who didn’t provide an answer in any of those formats – which left 270 participants. A more strict analysis that uses *only* the numerical responses results in the same observations listed above (e.g. the distribution is equally long-tailed and it appears to be log-normal).

This post significantly adds to the conversation in Effective Altruism about how pain is distributed. As explained in the review of Log Scales, understanding that intense pain follows a long-tail distributions significantly changes the effectiveness landscape for possible altruistic interventions. In particular, this analysis shows that finding the top 5% of people who suffer the most in a given medical condition and treating them as the priority will allow us to target a very large fraction of the total pain such a condition generates. In the case of cluster headaches, the distribution is extremely skewed: 5% of sufferers experience over 50% of all cluster headaches.

More so, the survey also showed that the leading cause for why sufferers don't use tryptamines to treat their condition is the difficulty of acquiring them. Thus, changing the legal landscape via e.g. providing programs for the easy access to tryptamines to sufferers of migraines and cluster headaches might be a very cost-effective way of massively reducing suffering throughout the world.

Zooming out, perhaps the significance of this goes beyond cluster headaches in particular: it perhaps hints at a more significant paradigmatic change for analyzing the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Generally I really find this research agenda interesting. I have only skimmed this post, but I also like your analysis the way you go about it.

One nitpick:

I think this is hyperbole. I reviewed the literature a while ago, and while I do agree that there is some suggestive evidence that this is true, I do not think that it is so strong as to warrant the claims you make and there are many qualifications. Also, I think you should cite the relevant studies on this subject (https://scholar.google.com/scholar?as_ylo=2015&q=LSD+cluster+headaches&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5).

Thank you. The survey said that 68% of sufferers who have used psychedelics found gave them a rating of 4 or 5, where 5 means “They have completely eliminated the cluster headaches”. I would certainly stand by the claim that "there are millions of people suffering needlessly from this condition who could be nearly-instantly cured with something as simple as growing and eating some magic mushrooms." We've interviewed people for whom sub-hallucinogenic doses of DMT and psilocybin took a 10/10 pain CH all the way to a 1/10 or 0/10. And in the case of DMT, due to its method of administration, this takes place within seconds (more than one but less than 10). Even if this works only for, say, 20% of the sufferers, it is still millions in absolute terms.

Thanks for saying: "Generally I really find this research agenda interesting". My experience has been that few people take seriously the long-tails of pleasure and pain. This is precisely the sort of missing piece of information that can add an entire new wing to EA.

For what it's worth, this seems like a pretty big deal to me if it were true. Is there any quick QALY estimate or similar for how much things can be improved if everyone had quick access to DMT or similar?

One quick thought: it could be neat experiment to make $2k of Facebook ads to target people with these issues, pointing to a specific webpage the discusses how these people could get treatment. That said, I of course realize some may not be legal, so it could be tricky.

Still seems worth it, FB might just eventually ban. ( I sort of doubt anything would happen if you link to an informational infographic)

In the article specifically about N,N-DMT as a possible treatment for CHs, Quintin added a rough QALY calculation (I should add that any QALY estimate concerning CHs and other ultra-painful disorders will typically severely underestimate the value of the interventions, given the logarithmic nature of pain scales):

Thanks!

Some quick thoughts:

One quick way to get people to not take you seriously is with a bad cost effectiveness estimate. There's a much bigger risk of doing a sloppy/overconfident job than benefit of having a high number at the end of it (in EA circles). Also, there is a reputation of these estimates to both produce amazing numbers and also be very wrong, so while I support attempts, I'd also recommend lots of clarification, hedging, and consideration of ways the number could be poor. I think the default expectation is for the number to not be great; but even if the median isn't good, it's possible upon further investigation it could be better than expected, which could be quite worthwhile.

"to reach all chronic sufferers" -> I'd recommend targeting 30%-60% of sufferers. The last several percent would be much more expensive.

I'm quite skeptical of the click -> cure stats in particular. For-profit websites often have a 1% rate of people who go from click -> purchase, and this could be a pretty significant amount of work to purchase.

Is this equation taking into account that the "cure" could last for many years? Would the result be in "QALYs per year"?

I'm sure you've answered this elsewhere, but why the American focus? Would it be possible in India or similar?

This estimation seems like something that Charity Entrepreneurship would have a lot more experience in. The program seems quite similar to some of their others.

I'd suggest reading up on the mini-fiasco of the leafletting research, if you haven't yet. Just make sure not to make some of the mistakes made around that. Some context: https://animalcharityevaluators.org/blog/ace-highlight-updated-leafleting-intervention-report/ https://acesounderglass.com/2015/04/24/leaflets-are-ineffective-tell-your-friends/ https://medium.com/@harrisonnathan/the-problems-with-animal-charity-evaluators-in-brief-cd56b8cb5908

Consider using Guesstimate for clarity, but I'm biased :)

Kudos for the efforts, and good luck!

I'm very excited to see people doing empirical work on what things we care about are in fact dominated by their extremes. At least after adjusting for survey issues, statements like

seem to be a substantial improvement on theoretical arguments about properties of distributions. (Personal views only.)

Maybe this is addressed somewhere and I've missed it, but "do you use tryptamines to treat your headaches" shouldn't be a yes/no question - shouldn't the options be "never tried," "tried and stopped for some reason" or "yes I use them to treat my headaches"?

It seems like the current framing is going to overrepresent people who find tryptamines helpful, because people who tried them and didn't find them effective or discontinued due to side effects are currently in the "don't use tryptamines" category.

That's a good point, thank you. We should distinguish between lifetime use and current use in future surveys. Perhaps even asking whether "they worked the first time you used them" to see if people who currently use them had a better reaction to their first try relative to those who did try them at some point but do not currently use them.

I would add that other reasons why people might have used them in the past but don't currently include "can't access it now", "too afraid of legal repercussions", and "social stigma". While discontinuing them due to side-effects and lack of effectiveness can make them look more effective than they are among the "use them" group, the other reasons for discontinuation do not have this effect. I don't know what % of past users discontinued for which reason, and that seems like a good thing to find out.

This is very interesting, thanks for doing this work.

I would note that members of a cluster headache subreddit are unlikely to be representative of the broader population that generated the 1/1000 figure. Presumably they experience a disproportionately large number of headaches.

I completely agree that the members of a cluster headache subreddit or facebook group are not necessarily representative, and in fact quite likely not representative at all.

I think that the conclusion that the distribution follows a long-tail regardless is still accurate. I reason this based on the following point: even if the probability of participating in the survey increased exponentially as a function of the number of times one experiences CHs per year (or sigmoid at the limit), you would nonetheless not be able to make a Gaussian distribution look like a log-normal. The reason is that the rate at which a Gaussian decreases is proportional to the inverse *squared* of the distance from the mean. So we would still get a net decrease at an exponential rate, which does not produce a long-tail (just a somewhat more bulky tail that still tapers off rather quickly). For it to exhibit a long-tail, the probability of participating in the survey as a function of the number of CHs per year would have to grow *doubly* exponentially, at which point we really run out very quickly of possible participants.

That said, I do agree that there is likely an over-estimation of the frequency, but I would argue due to the above reasons that such over-estimation can't account for the long-tail.

I'm less optimistic about the use of surveys on whether people think tryptamines will/did work:

You say 'we' (as in 'we are researching') a lot, but who are 'we'?

Depends on context. In most cases the 'we' refers to my team and I at the Qualia Research Institute. For example: "Since a number of interviews we’ve conducted have shown that even sub-hallucinogenic doses of DMT can abort cluster headaches" refers to QRI (with other members of the research group having conducted such interviews).

I should note that the word is also used in the 'didactic we' sense a number of times (as in "we will explore the era of the dinosaurs together" in a National Geographic documentary).

What do you make of Emgality? Looks like a relatively small effect, but the absolute effect could still be large given the severity of Cluster Headaches.

It's great that it works for some people, some of the time. In absolute terms, it is a massive good, so it should be promoted more. Pragmatically it might make sense to emphasize it right now given the low probability that DMT will be approved as a treatment in the next few years, so until then Emgality should be discussed more. That said, yes, in terms of % relief it still is in a completely different class than DMT. That is, it tends to reduce incidence rather than get rid of them, and it is only approved for episodic (rather than chronic) CHs, which account for a relatively small % of the number of CHs experienced, as described in this article (due to the long-tail).