Jack_S

Posts 3

Comments20

I haven't got a very well calibrated model, but I'm still fairly optimistic about alt proteins becoming increasingly commercially viable. I would update very little on 2022 being a fairly bad year for a few reasons:

- I don't think the article's claim that 'sales of PBM declined significantly in 2022' is actually true. According to the lastest GFI plant-based meat report: "...global dollar sales of plant-based meat grew eight percent in 2022 to $6.1 billion, while sales by weight grew five percent." In Europe, sales grew by 6%, so it's really just the US.

- In the US, "estimated total plant-based meat dollar sales increased slightly by 2% while estimated pound (lb) sales decreased by 4%" (GFI, 2023), so a very marginal decline in demand. I think the narrative that the market collapsed in 2022 is more due to the more significant decline in home/ refrigerated purchasing of PBM, and perhaps because Beyond Meat had an awful year.

- Other metrics are looking okay:

- Total invested capital in alt protein is still comparable with other food sectors, with major increases in cultivated and fermented meat investment.

- Government investment is growing and locked-in as part of multi-year programs in many countries

- Many new production facilities are springing up, which should reduce prices, especially for fermented and cultivated products.

- I think we've reached the turning point for national safety approvals for cultivated meat, and I expect more (such as China and Japan) in 2023-2024

- There has been some pretty considerable investment in certain emerging markets (APAC and MENA) - Even if it has been a bad year in some respects, it's been a bad year for everyone. Conventional meat sectors have also suffered in 2022- particularly in the UK and EU. And growing tech sectors have also slowed - quantum computing investment also flattened off from a rapid growth trajectory.

So I wouldn't update too much on 2022's slowdown- it's a combination of macroeconomic factors, Russia-Ukraine, high interest rates and rising energy prices that have reduced investment, and inflation that's led to reduced consumption.

As for your question of whether alternative proteins will take off. I'm optimistic. I think we've entered a situation where:

- Many conventional/ institutional food producers have bought into alt proteins, so there's less institutional resistance

- Most governments are at least partly supporting the transition to alt proteins, especially import-dependent countries with food security issues like Israel, Singapore and the UEA

- Young people across a lot of the world are increasingly into alt proteins (especially milks), so the demographic shift will work in favour of alt proteins over the next decade

I feel that we have the right incentives and technology to produce super tasty, affordable alternatives for various consumer types, and when we get these products, the market should start to grow.

The reasons I could be wrong might be:

- We'll continue to lack those killer products at an affordable price. The market will be dominated by poor, low-cost products, giving alt protein a worse reputation among many normal consumer groups.

- It's only ever going to be a niche market. Almost everyone actually prefers conventional meat, and most consumers are more resistant to change than we currently think. Cell-cultivated meat will be seen as the only viable alternative, and people will continue consuming conventional meat until cell-cultivated meat hits price parity.

I'd argue that EA is quite bad at something like: "Engaging a broad group of relevant stakeholders for increased impact". So getting loads of non-EA people on your side, and finding ways to work together with multiple, potentially misaligned orgs, governments and individuals.

Don't want to overstate this- some EA orgs do this well. Charity Entrepreneurship include stakeholder engagement in their program, for example. But it seems neglected in the EA space more generally.

Yeah, makes sense. I just don't know why it's not just: "It's conceivable, therefore, that EA community building has net negative impact."

If you think that EA is/ EAs are net-negative value, then surely the more important point is that we should disband EA totally / collectively rid ourselves of the foolish notion that we should ever try to optimise anything/ commit seppuku for the greater good, rather than ease up on the community building.

I definitely don't think it's too much to expect from a self-reflection exercise, and I'm sure they've considered these issues.

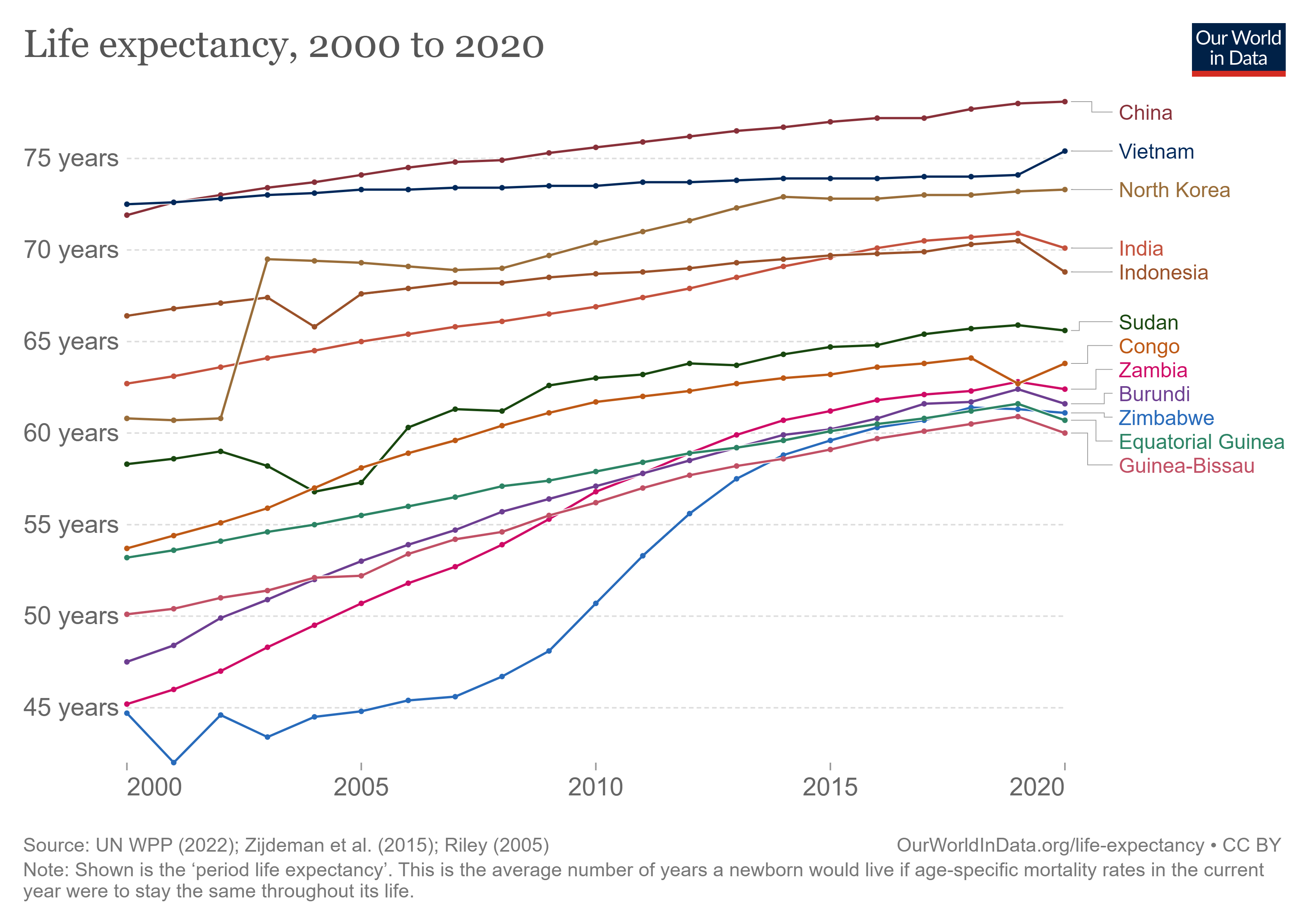

For no. 1, I wouldn't actually credit growth so much. Most of the rapid increases in life expectancy in poor countries over the last century have come from factors not directly related to economic growth (edit: growth in the countries themselves), including state capacity, access to new technology (vaccines), and support from international orgs/ NGOs. China pre- and post- 1978 seems like one clear example here- the most significant health improvements came before economic growth. Can you identify the 'growth miracles' vs. countries that barely grew over the last 20 years in the below graph?

I'd also say that reliably improving growth (or state capacity) is considerably more difficult than reliably providing a limited slice of healthcare. Even if GiveWell had a more reliable theory of change for charitably-funded growth interventions, they probably aren't going to attract donations- donating to lobbying African governments to remove tariffs doesn't sound like an easy sell, even for an EA-aligned donor.

For 2, I think you're making two points- supporting dictators and crowding out domestic spending.

On the dictator front, there is a trade-off, but there are a few factors:

- I'm very confident that countries with very weak state capacity (Eritrea?) would not be providing noticeably better health care if there were fewer NGOs.

- NGOs probably provide some minor legitimacy to dictators, but I doubt any of these regimes would be threatened by their departure, even if all NGOs simultaneously left (which isn't going to happen). So the marginal negative impact of increased legitimacy from a single NGO must be very small.

On the 'crowding out' front, I don't have a good sense of the data, but I'd suspect that the issue might be worse in non-dictatorships- countries/ regions that are easier/ more desirable for western NGOs to set up shop, but where local authorities might provide semi-decent care in the absence of NGOs. This article illustrates some of the problems in rural Kenya and Uganda (where I think there's a particularly high NGO-to-local people ratio).

I suspect GiveWell's response to this is that the GiveWell-supported charities target a very specific health problem- they may sometimes try to work with local healthcare providers to make both actors more effective, but, if they don't, the interventions should be so much more effective per marginal dollar than domestic healthcare spending that any crowding effect is more than canceled out. Many crowding problems are more macro than micro (affecting national policy), so the marginal impact of a new effective NGO on, say, a decision whether or not to increase healthcare spending, is probably minimal. When you've got major donors (UN, Gates) spending billions in your country, AMF spending a few extra million is unlikely to have a major effect. But I'm open to arguments here.

This definitely crossed my mind. Assuming he expected it to be published and he'd guess how bad his responses would look, this would be one of the few rational explanations for his sudden repudiation of ethics.

But it also seems fairly likely that his mind is in a pretty chaotic place and his actions aren't particularly rational, though.

Thanks for writing this, great to hear that you're feeling better.

I'm usually a fan of self-experimentation, and the upside of finding an antidepressant with few side-effects (and that you can take a lower dose of) is definitely valuable. This seems especially true if you can stop taking it during better mental health periods, then have it in your arsenal for future use. But I still have a few doubts about this process, and I'm a little concerned that some of the premises behind your experiment need a bit more scrutiny. I hope someone with a bit more domain-specific knowledge can correct me if I'm wrong, or improve my arguments if I have a point. I'm also aware that there's no such thing as a 'perfect self-experiment', and I don't think there are obvious ways that you could have improved the experiment. But here are a few things that I'd like to hear your thoughts on:

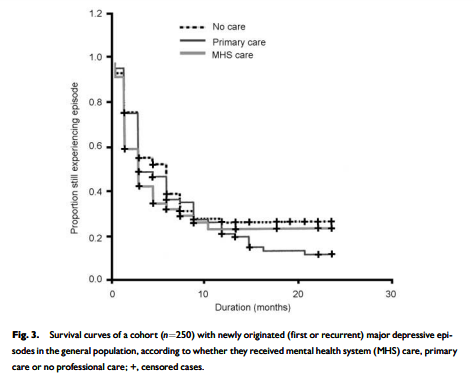

Firstly, the depression episode was triggered by an disruptive external factor- the pandemic. This would probably invalidate any observational study held in the same period. As this external factor improved, and people could start travelling/ socialising normally, you might expect symptoms to lift naturally from mid-2021 onwards. From what you've mentioned here, you don't seem to have disproved this hypothesis. I gather that depressive episodes seem to last a median of about 6 months ( see pic below), with treatment not making a huge difference for duration within the first year (some obvious caveats about selection effects here). How do you consider the possibility that you would have recovered without antidepressants?

Secondly, the process of switching between 5/6 antidepressants seems to be a significant confounding factor here. I don't know how good the evidence base for the guidelines link you sent was, but it seems likely that the multiple (start, side-effects, ending, potential relapse) effects of antidepressants are significant enough to really mess up any attempts to have a 'clean slate' between treatments, and to therefore make it a unfair comparison. It seems possible that what you thought was a negative reaction to x medicine was actually contingent on having just tapered off y medicine and/ or experiencing a relapse. Does that seem plausible, or do you think that there was a stable enough baseline for comparisons to be valid?

Third, just a bit of concern about the downsides of the experiment. There are some long-term side-effects to antidepressants, and they seem understudied for fairly obvious reasons (most clinical studies only last for 6 months, no long-term RCTs). There seems to be a few studies that point to longer-term risks and 'oppositional effects' being underestimated. Unknown confounding factors and additional health risks from going on and off antidepressants would make me very concerned. Obviously, untreated depression also has a range of health risks, so I don't want to discount the other side of the ledger, but I would definitely not be confident that I was doing something safe. How confident do you feel in your comparison of these risks? And did you feel that you had to convince yourself against (potentially irrational) fear of over-medication?

Finally, a bit unrelated, there's a meta question that often comes to mind when I read posts about more rational/ self-experimenting approaches to health issues, which is: "How strong should our naturalistic bias/heuristic be when approaching mental health/ general health issues?" Particularly for my own health, I have a moderate bias against less 'natural' (obviously a very messy term, but I think it's useful) health solutions. I often feel EAs have the opposite bias, preferring pharmacological solutions, perhaps because they can be tested with a nice clean RCT. I'm interested what level of bias you, (and forum readers), think is optimal.

If I recall, it was only really in the 2010s, following the release of this study (catchily named HPTN 052), that we realised that ART/ ARV was so effective in stopping HIV transmission, so I think that was a justifiable oversight.

Assuming that prices will remain constant seems to be a genuine issue - I think we need to think about this more when we look at cost-effectiveness generally - but I have an inkling as to why this might be common.

In Mead Over's (Justin's colleague) excellent course on HIV and Universal Health Coverage, we modelled the cost effectiveness of ART compared to different interventions. The software package involved constant costs for ART (and second line ART) as a default setting, and didn't assume that there would be price reductions. I didn't ask why this was, but after adding price reductions to the model for my chosen country (Chad), I realised that the model then incentivises delaying universal ART within a country, and instead focusing on other interventions which are less likely to decrease in cost over time.

Delaying might be wise in some contexts, but I'm sure many health ministers are just looking for excuses to delay action (letting other countries bring the price down first), so politics doubtless plays a role.