geoffrey

Bio

Research Assistant at World Bank DIME. DC-based. I like talking about development, economics, trade, and DEI.

How I can help others

Happy to chat about

- teaching yourself to code and getting a software engineer role

- junior roles at either World Bank or IMF

- picking a Master's program for transitioning into public policy

- selling yourself from a less privileged background

- learning math (I had a lot of mental blocks on this earlier)

- dealing with self-esteem and other mental health issues

- applications for Econ PhD programs (haven't done it yet, but people are surprised by how much I thought about the process)

Fastest way to reach me is geoffreyyip@fastmail.com but I do check messages here occasionally

Comments33

I think this falls into a broader class of behaviors I'd call aspirational inclusiveness.

I do think shifting the relative weight from welcoming to clear is good. But I'd frame it as a "yes and" kind of shift. The encouragement message should be followed up with a dose of hard numbers.

Something I've appreciated from a few applications is the hiring manager's initial guess for how the process will turn out. Something like "Stage 1 has X people and our very tentative guess is future stages will go like this".

Scenarios can also substitute in areas where numbers may be misleading or hard to obtain. I've gotten this from mentors before, like here's what could happen if your new job goes great. Here's what could happen if your new job goes badly. Here's the stuff you can control and here's the stuff you can't control.

Something I've tried to practice in my advice is giving some ballpark number and reference class. I tell someone they should consider skilling up in hard area or pursuing competitive field, then I tell them I expect success in <5% of people I give the advice to, and then say you may still want to do it because of certain reasons

Yes, it's all very noisy. But numbers seem far far better than expecting applicants to read between the lines on what a heartwarming message is supposed to mean, especially early-career folks who would understandably assign a high probability of success with it

Congrats on passing your first year. Some off-the-cuff thoughts from someone still trying to get to where you are and spent a lot of thing on EconTwitter figuring stuff out:

- I read online that 2nd econ phd year is usually the best year. Field courses I hear are a treat. If you're not feeling that year, it's unlikely the rest of the academic path will sustain your interest.

- I think year 3 is where you can possibly have your first test bet, since it's the first solo year. I also hear it's the easiest to slack off in. A recurring joke I've seen among faculty tweets is "we still don't know what our students do in their 3rd year, but we know it takes them a year"

- I recall a Twitter poll that listed econ PhD year 1 as the highest work hours per week (compared to 2nd year, 3rd year, 4/5th year, job market year, tenure track, tenured). If the 5 days on 2 days off is what you miss, I suspect you'll swing partly back towards that, which may help.

- The wealth of peers with similar interests is a big reason why I'd considering PhDs. I do think you'll have trouble finding that outside the PhD. That said, you'll still have those connections and if EconTwitter doesn't blow up, you can have that as kinda surrogate connection feeling.

- I'd separate working on treatment spillovers and growth. Treatment spillovers feels like a measurement and impact evaluation thing, which does seem very academic-research-loaded. But growth is the outcome and working on growth can mean many things (which is one of my frustrations when people say we should work on economic growth. It as specific as saying you want to work on non-global-health systemic change).

- In the real world, very few roles work on growth theory or policies for aggregate growth directly. It's usually some piece, like infrastructure or corruption or business liberalization or so forth. Some might have a growth model as their motivation, but for most people the motivation is as simple as "this is a big problem with big upside, let's work on it". If that more growth-adjacent less-evaluation-rigor stuff appeals to you, the PhD is less crucial.

- As an aside, to my knowledge, most trade econ doesn't work on country-level growth directly or stuff relating to that. That seems to result from the history of trade methodology, where it's very micro focused. There is stuff on firm productivity growth in the "new new trade theory" (look up Melitz) though it's unclear how that aggregates up into broader welfare gains. I do know there's a macro-trade / computable trade niche of stuff going on, but I'm less familiar with those, and that community feels like it's closer to macro than trade.

I've found a lot of professional overlap between groups focused on global health and groups focused on LMIC growth (low-and-middle-income country growth). Each group tends to be the biggest audience and best critic of the other approach.

I'm not sure if breaking out the topic would incentivize more attention of LMIC growth, but I do worry we'd lose some interesting discussion.

Try "managing up" with a simple text document during meetings.

I'm the main contributor on a project with a light management layer. The autonomy' s nice. But it's given a lot of space for stakeholders to spend check-ins talking about their long term wish list (which is fun for them) while avoiding the prioritization I need them to do.

Recently, I started bringing a text document into check-ins on my understanding on what the priorities, editing it as the meeting goes, and assigning items as (In progress), (todo), or (nice-to-have). It's Kanban in spirit but without the overhead of actually running Trello / Jira/ Notion.

Here's some extra (low confidence) info regarding financial aid:

Some programs will have a link on their website where you can talk to a program coordinator or admissions officer. Talking to this person before you apply and forming a good impression may help you secure a much nicer financial aid package when you get accepted. This varies by school and it's luck-of-the-draw whether you hit it off with someone. Generally, you should be genuine and approach the meeting with curiosity over topics like when certain faculty teach. But that person may have info on how to best negotiate financial aid or they may even be able to champion the financial aid package for you internally.

Diversity-based aid is extremely rare and I don't know anyone who's personally gotten it. But I think if you have a especially rough hardship story or rare background for your field (the kind that warrants a local newspaper article or university profile) AND you're a good student, you're likely to get some money for that.

Finally, if you're price-sensitive and willing to take some risk, newer Master's programs and/or lower-tier programs tend to offer generous packages because they're trying to establish their brands. I wouldn't recommend this, but if you just want the credential, this does get you through at a lower price. Or if you know and trust one of the program coordinators / faculty personally, maybe you could take a risk at a newer program.

Hi Caspar,

Thanks for the response. On second thought, my objection might be different than what I initially suggested. I do think the test of overlap of scales as you mentioned would be an interesting test to run, but it doesn't seem to be capturing the overlap I ultimately care about.

Maybe this comment can captures my complaint better. We don't have any access to what "the most/least satisfied that any human could possibly be". We don't even have access to "the most/least satisfied you personally think you could become".

As a personal example, I would take most of my worst post-therapy days over most of my best pre-therapy days. Younger me has no access to realizing how much satisfied I could be with life, or even how broadly people are in general.

I might be using the language wrong, but I think I'm hinting at differences in the latent scale of well-being or satisfaction... which doesn't feel like it's knowable.

I enjoyed this a lot. I've been meaning to delve into well-being measurement and this was a nice entry-point into the field.

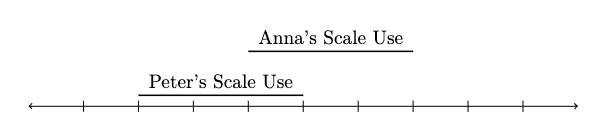

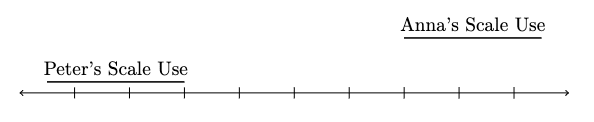

One thing I'm not clear on is whether vignette anchors (or any of the comparability methods) can correct for non-overlapping well-being scales. You talked about an example like this:

But I'm more interested in examples like this:

Measuring these larger SWB (subjective well-being) differences seems crucial for detecting interpersonal differences across societies and picking up on how intense pain / pleasure can be at the long tails. The non-overlap area seems like it can get extremely big.

Hi Niki, glad to hear it helped. Here's some more thoughts. Can't promise they're any good.

Yes, I agree the consumption smoothing point is critical. I could have worded my answer a bit better. What I meant to say is that rural households are good at trying to smooth consumption given their situation. That can still be a low overall ability given how sporadic income can be. The crux, I suppose, is whether we trust the households to smooth their own consumption or if we should make the decision for them. If we think the households are better able to make the decision, we send the transfer now. If we think they're worse (perhaps for lack of willpower reasons), then we delay.

From the dataset I linked you, it's tough to decompose the idiosyncratic shock from just family-level income / consumption / wealth data. You'd want to correct for village-level shocks and seasonality and so on. I believe it's do-able but noisy. And it's usually cleaner to simply ask the families whether they suffered from X adverse event in the past 12 months (which the India Human Development Survey does ask).

To do this more cleanly, you'd want a dataset that interviews each family multiple times in a single year. Then you could see the variability in income / consumption / wealth over time per family.

I'm not familiar with how GiveDirectly does their operations, but I'd be surprised if the communication was frequent enough that GiveDirectly staff could observe and react to every family illness in real-time.

On systemic shocks, you might be right. I was envisioning a bad natural disaster where the logistics of shipping more food out to villages is temporarily clogged up. But perhaps NGOs are more crafty that I think.

(Some quick thoughts hastily written based off some class papers I wrote a while back.)

One dataset that pops to mind is the India Human Development Survey. This is a rich household-level dataset that includes total household monthly income (disaggregated by source) and if I recall right, also tells you what month it is. These are time-intensive to work with, but I imagine a few others datasets like this exist in the world. And you can estimate "income" per month with them.

My guess is you'll get obvious insights from this, like income dropping during cold / dry seasons in more agricultural-dependent villages.

That said, my gut feeling with the policy question is that sending cash transfers sooner is better. A few reasons:

- The book Portfolios of the Poor suggests rural households, especially poor ones, are good at managing their own finances and spreading out their resources over time (or consumption smoothing as economists call it).

- Household debt (not captured in income) may accumulate interest, and interest rates can be exorbitantly high.

- Idiosyncratic shocks (like a family illness) are hard to surveil and predict from afar. So it's hard to implement strategic delays

- Extreme systemic shocks like very harsh droughts / floods may temporarily constrain food / fuel supply reducing effectiveness of cash transfers at that time.

- Households may want to stock up on durable foods like grains or oils ahead of time

- Counterintuitively, giving money while households have high-income may push them over a wealth-threshold that lets them make durable investments (roofs, goats, farm equipment). This may be welfare-enhancing in the long run. I think this goes by the "lump-sum" effect in the cash transfers literature.

Hope this helps. Happy to chat about this more.

Like this a lot, especially the plot designs.

Surprised there’s not much in demographic differences even with all the caveats that go with interpreting disparities there. Not sure what to make of that yet but will be chewing on that for a while.

Lastly, got a question. Do you have any sense of what a good baseline for the mental health section might be? The question of “has your mental health increased / decreased/ stayed the same since getting involved with X” is new to me