Noah C Wilson | Noah.C.Wilson1993@gmail.com

Key Takeaways:

- Building a massive mainstream global movement is essential to achieving safe AGI.

- AI outreach has become the most urgent cause in AI safety due to accelerating timelines. AI outreach remains underemphasized compared to technical AI safety research.

- A pilot study I conducted found that influencing AI risk sentiment is highly tractable. I used snapshot explainer interventions to successfully influence the concern about AI risks and support for AI regulation in a sample of 100 participants.

- This study also investigates more and less effective means of influencing this sentiment.

What is AI Outreach?

AI outreach is the process of informing and engaging the general public about the risks posed by artificial intelligence, with the goal of growing the AI safety movement to foster an informed and cautious societal response. This includes conveying catastrophic concerns in an accessible way, countering misconceptions, storytelling, media engagement, and cultural interventions that reshape how AI is perceived and discussed.

Why Do AI Outreach? I.T.N. Framework

AI Outreach is Important

When we look at history, the most significant societal shifts—especially in response to existential risks—didn’t happen because a few experts had quiet conversations behind closed doors. They happened because public sentiment changed, and in doing so, forced institutions to respond.

This pattern repeats across some of the most pressing challenges humanity has faced:

- Nuclear Disarmament Movements – The fear of nuclear war was abstract to policymakers in the 1950s, but mass movements like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the Nuclear Freeze Movement turned it into a crisis the public cared about. Protests, advocacy, and cultural shifts (think: "Dr. Strangelove" and the Doomsday Clock) created real pressure that led to treaties like the Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963) and, later, the INF Treaty (1987). Governments moved because people demanded action. [1]

- Climate Change Activism – The science on climate change was clear decades before governments acted meaningfully. What changed? Movements like Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, and the broader environmental movement shifted public perception. This, in turn, made climate action politically viable, leading to policies like the Paris Agreement (2015). Again, mass sentiment was the forcing function. [2]

- AI Safety Awareness & Pause AI Movement – Just a few years ago, AI existential risks were considered niche concerns. Then, a combination of public advocacy, media attention, and high-profile figures speaking out made AI safety a more prominent issue. The "Pause AI" open letter, signed by AI leaders and experts, didn’t achieve an immediate pause—but it shifted the Overton window. AI risk is now on the global policy agenda, leading to initiatives like the UK AI Safety Summit and the US AI Executive Order.

AI safety has moved from obscurity to a more prominent issue, but it has not yet become a massive mainstream concern. History shows that public concern drives government action—not the other way around. AI safety isn’t going to be solved just by technical research or policy papers alone. The levers of power respond to public pressure.

If we want safe AI, we need to build a massive movement. A movement that shifts AI safety to an issue the world demands action on.

AI Outreach is Urgent:

- Short AGI timelines are now the mainstream expectation. Sam Altman (OpenAI) and Dario Amodei (Anthropic) have both recently stated that they expect AGI within the next three years. [3]

- Ajeya Cotra has significantly shortened her timeline estimates. Her median prediction now places full automation of remote jobs in roughly 6–8 years—at least five years earlier than her 2023 estimate. [4]

- Prediction markets reflect an accelerating timeline. Platforms like Metaculus and Manifold now have median AGI estimates around 2030, suggesting a growing consensus that AGI is coming sooner than previously expected. [5]

- AI performance keeps surpassing expectations. Benchmark results continue to exceed expert predictions. Most recently, OpenAI’s o3 model scored 25% on Epoch’s Frontier Math dataset—far beyond what many expected. It also showed unexpectedly strong coding abilities. [6]

- In real-world applications, AI is already matching top human experts and seems likely to surpass them soon.

Implications:

- Long-term safety plans may be irrelevant. Strategies that depend on multi-year timelines should be discounted if they assume AGI is still 5+ years away.

- This is not to say technical safety research is not important. In fact it is paramount to eventually achieving safe AGI. This is also not to say that AGI will definitely arrive within the next 5 years. However, for individuals who are not in a position to do meaningful technical safety work within the next ~3-5 years, AI Outreach may be the most impactful use of resources.

- AGI could arrive under a Trump presidency. If timelines hold, there’s a real possibility that AGI will emerge while Trump is in office, which has implications for governance, policy, and mass movement building.

AI Outreach is Tractable

In my pilot experiment, detailed later, participants engaged with educational material on AI's catastrophic risks for an average of just three minutes. These three minutes were quite impactful: 79% of respondents reported increased concern about catastrophic risks, with 21% describing themselves as "much more concerned." Additionally, 80% became more supportive of federal AI regulations, with 32% becoming "much more supportive."

These findings underscore that brief, targeted educational interventions can effectively raise awareness and concern about catastrophic risks from AI.

Based on a 2023 survey conducted by Rethink Priorities, the U.S. public is likely to be broadly receptive to initiatives aimed at addressing AI risks—particularly those perceived as both plausible and highly concerning. Since AI risk is still a relatively new topic in public discourse, ongoing events and media coverage have the potential to significantly shape public perception. [7]

Two key findings from this survey are quite striking when juxtaposed [7]:

- “9% think AI-caused extinction to be moderately likely or more in the next 10 years, and 22% think this in the next 50 years.”

- “Worry in everyday life about the negative effects of AI appears to be quite low. We estimate 72% of US adults worry little or not at all about AI, 21% report a fair amount of worry, and less than 10% worry a lot or more.”

If 22% percent of people believe that AI-caused extinction is moderately likely in the next 50 years, we should expect at least 22% of people to “worry a lot or more” about AI risks. A similar poll conducted by YouGov found an even higher percentage of people view AI-caused extinction as plausible - 17% reported it ‘very likely’ and a further 27% reported it ‘somewhat likely’ that AI will lead to human extinction. [7]

Another indicator that AI outreach is highly tractable is that the public seems broadly aware that AI will likely become more intelligent than humans (67% think it is at least moderately likely) but don’t seem to appreciate the implications (72% of adults worry little or not at all about AI risks) [7]. In my pilot study, after subjects read a single explainer article on superintelligence (a three minute read, based on Ajeya Cotra’s young business person example [8]), 52% became moderately or much more concerned about catastrophic risks from AI and 56% became moderately or much more supportive of federal regulations of AI.

By strategically disseminating accessible and compelling information, we can meaningfully influence public sentiment and foster a more informed dialogue around AI safety.

AI Outreach is Neglected

For a while after ChatGPT’s release, AI risk seemed like it had secured a place in mainstream discourse. High-profile efforts, like the CAIS AI Extinction Letter, brought the issue to the forefront with big-name signatories and widespread media attention. But over the past couple of years, existential risk from AI has mostly dropped out of major media conversations. Even recent AI developments with serious implications for AGI timelines and catastrophic risk—like DeepSeek and Stargate—haven’t sparked much safety-focused coverage.

A clear example of the AI safety community’s struggle to influence media narratives was the OpenAI board saga. Instead of framing the discussion around AI risk and governance, the dominant story became a corporate drama about leadership battles and company direction—leaving AI safety concerns on the sidelines.

Right now, the AI x/s-risk conversation isn’t gaining ground where it matters most. Public concern about AI exists, but it’s not being translated into meaningful discourse or policy pressure. If we want AI safety to remain a central issue, we need to actively work to get it into the conversation. Media coverage doesn’t just happen—we have to make it happen.

A key finding from Rethink Priorities that summarizes how outreach efforts have been neglected within AI safety: “US adults appear to appreciate that AI may well become more intelligent than people, and place non-negligible risk on the possibility that AI could cause extinction within the next 50 years. Nevertheless, people generally expect there to be more good than harm to come from AI.”

Despite widespread agreement among AI and existential risk experts that AI poses one of the most credible threats to human survival, this awareness hasn't been translated to the public.

- AI barely registers as an existential risk. In a survey ranking potential extinction threats, only 4% of respondents thought AI was the most likely cause—ranking it below all four other threats included in the study. For comparison, 42% selected nuclear war as the top risk, while even pandemics—despite being considered less likely—were chosen by 8% of people. [7]

- Public support for regulation exists, but concern is shallow. Research suggests that while the public leans toward caution and regulation of AI, concerns about AI x-risk aren’t a dominant part of the existential risk conversation.

AI safety has public support, but it isn’t a priority. People aren’t inherently opposed to regulating AI, but they don’t yet see it as a crisis. That’s a massive gap—and one we urgently need to close.

Theory of Impact

Technical AI safety research is essential—but given current AGI timelines and the overwhelming market pressures driving AI development, it’s unlikely that safety research will “catch up” before someone builds AGI. Right now, AI capabilities are accelerating far faster than our ability to ensure they are safe.

To achieve safe AGI, we need robust safety research that can conclusively demonstrate AI systems are safe before they are deployed or tested. But for that research to even have a chance of success, we need more time—a dramatically longer timeline to AGI. And the only way to get that time is through societal, political, and policy pressures that can counteract the immense market incentives driving the AI arms race forward.

Market incentives and international competition mean that AI companies are not going to voluntarily slow down. If anything, they have every reason to push even faster. The only way to counter this dynamic is to build a massive mainstream global movement—one strong enough to force governments to intervene and coordinate an international response to slow down AI development until it can be made safe.

The goal isn’t to spread panic or fear-mongering. It’s to make AI safety a serious, mainstream global priority, on the level of nuclear nonproliferation. Just as the world rallied around nuclear risks in the mid-20th century, we need AI safety to be recognized as an urgent and unavoidable challenge that demands coordinated action.

How to do Effective AI Outreach

Personal Experience

As I have become more informed about the risks associated with AI, particularly catastrophic risks, these topics have increasingly shaped my conversations with friends and family. I have been struck by how challenging it is to persuade the average person—someone with a general awareness of AI who may occasionally use chatbot assistants but doesn’t engage with AI tools or conversations significantly—to take catastrophic risks seriously and see them as serious real-world concerns rather than far-fetched science fiction.

A common theme of skepticism in these conversations is along the lines of “there are always concerns that new technology will disrupt society and cause catastrophes, but each time it doesn’t happen”. And this is true, we can find a lot of examples of mass hysteria around technological advances:

- The printing press

- Vaccines and genetic engineering

- Prior waves of automation

- The internet

- Nuclear technologies

In general I found addressing this idea head-on with an argument along the lines of “there is no fundamental rule of physics or biology that says humans always pull through, or that because prior existential technology concerns have been near-misses, future ones will be too” seems to temper skepticism in some people. An argument that points out that risks from nuclear technologies have been mitigated thanks to valid global mass concern was also generally effective. An argument that simply says the “experts are concerned so you should be too”, seemed effective on some people but less so on others.

Another common theme of skepticism I noticed is along the lines of “AI is just a machine, it doesn’t have desires or motivations like a living creature, why would it ever become malicious or act in unpredictable ways in the first place?”. For this theme of skepticism I found a brief explanation of the concept of a rational agent and convergent instrumental goals to be effective. An explanation of AI literal-goals (a.k.a. “reward-hacking” or “specification-gaming”[9]) and what that implies for a smarter-than-humans AI, was also often effective.

This was just my personal anecdotal experience. Because I have become so oriented around massive mainstream global movement building as the key to safe AGI, I want to scientifically investigate what methods are most effective and compellingly convey the risks.

My experience repeatedly having these types of conversations gave me an overall impression that skepticism about AI risks does not stem from a disagreement that the risks are valid, it stems from a lack of understanding of what the risks are.

I was strongly influenced by a number of pieces of material from prominent authors in AI Safety, the friends and family members I could convince to read some of these pieces also seemed strongly influenced.

Pilot Study

Abstract

This pilot study investigates whether snapshot explainer interventions can influence individuals' concern about catastrophic AI risks and their support for AI regulation. Using a between-subjects design, 100 U.S.-based participants were randomly assigned to read one of four different educational materials, each representing a distinct argument for AI risk. Participants then rated how the reading impacted their concern about AI risks and their support for AI regulation.

Results indicate that brief educational interventions can significantly shift public perception: 79% of participants reported increased concern about AI risks, and 81% reported greater support for regulation. While a one-way ANOVA did not find statistically significant differences between the four materials, preliminary findings suggest that a hypothetical "gradual loss of control" scenario may be particularly effective at increasing concern and support for regulation. Effect size calculations indicate a moderate impact on shifting concern (Cohen’s f = 0.228) and a small-to-moderate impact on shifting support for regulation (Cohen’s f = 0.176).

These results confirm that influencing public perception of AI risks is highly tractable through short-form educational interventions. Future research with larger sample sizes should further explore which messaging strategies are most effective and how different media formats impact public concern and policy attitudes toward AI.

Introduction

To begin investigating what information and persuasive techniques are most effective at shifting concern about AI risks, I conducted a small pilot study with 100 U.S.-based participants. In this study I asked participants to read different pieces of educational material about AI risks, then asked them how that reading impacted their concern about catastrophic risks from AI and how it impacted their support for federal regulation of AI.

In this study I aimed to answer two questions:

- Can an individual’s level of concern about catastrophic AI risks be influenced through snapshot explainer interventions?

- What educational interventions are most effective at influencing an individual's level of concern?

Methods

I curated four sample materials derived from compelling writings on AI risks that I have relied on in discussions with skeptics.

These materials represent four different angles on why catastrophic risks from AI are real:

- Experts are concerned about existential risks from AI

- AI interprets goals literally and seeks convergent instrumental goals

- Implications of superintelligence depicted through 8-year old analogy

- Gradual loss of control of AI depicted through a hypothetical story

These materials are available in Appendix A.

I created four separate surveys using Google Forms and structured this study as a between-subjects design, meaning each participant was exposed to just one piece of material, after which the impact of the reading was measured with two multiple choice questions:

- Has this reading impacted your concern about catastrophic risks from AI (such as loss of control or human extinction)

- Less concerned

- No change

- Slightly more concerned

- Moderately more concerned

- Much more concerned

- Has this reading impacted your views on federal regulation of the AI industry?

- Less supportive of regulating AI

- No change

- Slightly more supportive of regulating AI

- Moderately more supportive of regulating AI

- Much more supportive of regulating AI

These surveys (no longer accepting responses) can be viewed at the links in Appendix B.

I first conducted a “pilot pilot study” by recruiting 20 volunteers (five per piece of material) from my friends and family to validate the functionality of the surveys and coherence of the written material. Results from this initial run were promising and indicated that influencing an individual’s perceptions of AI risks was indeed tractable, it also provided average response-times for each question to inform an estimate of costs to recruit a larger sample.

Next I recruited an additional 80 respondents (twenty per piece of material) using Prolific for a total cost of $125.71. These respondents were all US based and constrained to participating in only one survey, no other prescreens were used to filter the sample.

Results

Overview

To assess relative efficacy of each piece of material, I assigned point values to each multiple-choice answer option as follows:

- -1: Less concerned/Less supportive of regulating

- 0: No change

- 1: Slightly more concerned/Slightly more supportive of regulating

- 2: Moderately more concerned/Moderately more supportive of regulating

- 3: Much more concerned/Much more supportive of regulating

Averaged across all 100 participants and all four pieces of material, I found:

- Respondents spent an average of just 3:01 engaged in the survey including reading the material, answering the two assessment questions, and entering prolific account information to receive payment.

- Respondents level of concern shifted by an average point value of 1.50

- Respondents level of support for regulating AI shifted by an average point value of 1.70

- 79% of participants were at least slightly more concerned.

- 2% less, 19% no change, 27% slightly, 31% moderately, 21% much more concerned.

- 81% of participants were at least slightly more supportive of regulating AI.

- 1% less, 19% no change, 21% slightly, 27% moderately, 32% much more supportive.

Analysis

One-Way ANOVA

Change in concern: F = 1.67, p = .179

Change in support for regulation: F = .99, p = .400

Interpretation: Since both p-values are above the conventional threshold of 0.05, we do not have sufficient evidence to definitively conclude that there is a significant difference in effect across the four different pieces of material.

Effect Size

Change in concern: Cohen’s f = 0.228

Change in support for regulation: Cohen’s f = 0.176

Interpretation: The effect size for concern change (0.228) represents a medium effect, meaning the material presented had a moderate impact on shifting concern levels.

The effect size for support change (0.176) is between small and medium, suggesting that the material had a noticeable but weaker effect on increasing support for AI regulation.

The full data is available in Appendix C.

Breakdown by Material Presented

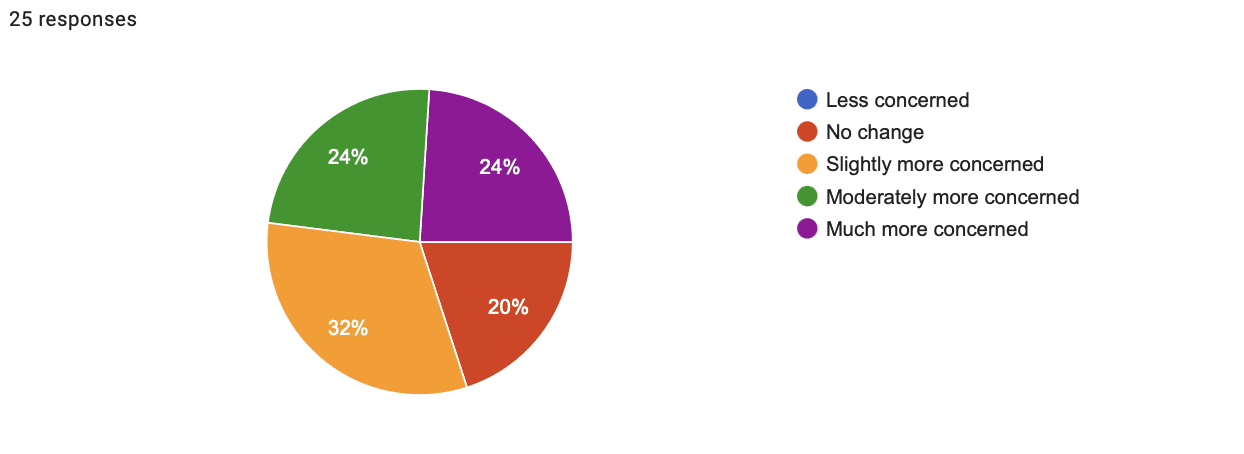

For each of the following conditions, the figures presented are averaged across the 20 participants in the respective condition.

Experts Views:

- Time: 1:37

- Shift in concern: 1.52

- Shift in support for regulating AI: 1.56

- Shift in concern response breakdown:

- 0% less concerned

- 20% no change

- 32% slightly more concerned

- 24% moderately more concerned

- 24% much more concerned

- Shift in support for regulating AI response breakdown:

- 4% less supportive

- 24% no change

- 12% slightly more supportive

- 32% moderately more supportive

- 28% much more supportive

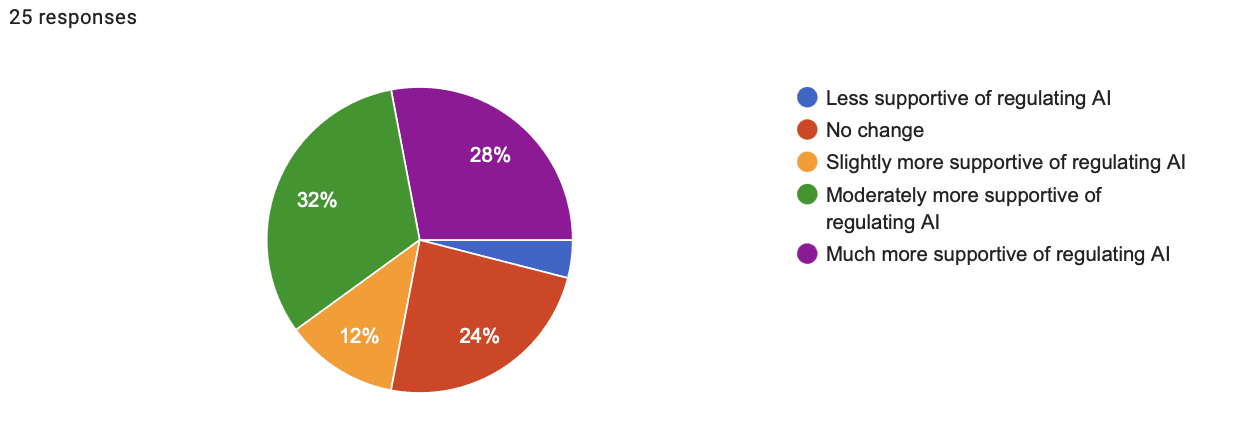

Literal Goals/Instrumental Convergence

- Time: 3:05

- Shift in concern: 1.24

- Shift in support for regulating AI: 1.60

- Shift in concern response breakdown:

- 4% less concerned

- 24% no change

- 32% slightly more concerned

- 24% moderately more concerned

- 16% much more concerned

- Shift in support for regulating AI response breakdown:

- 0% less supportive

- 24% no change

- 24% slightly more supportive

- 20% moderately more supportive

- 32% much more supportive

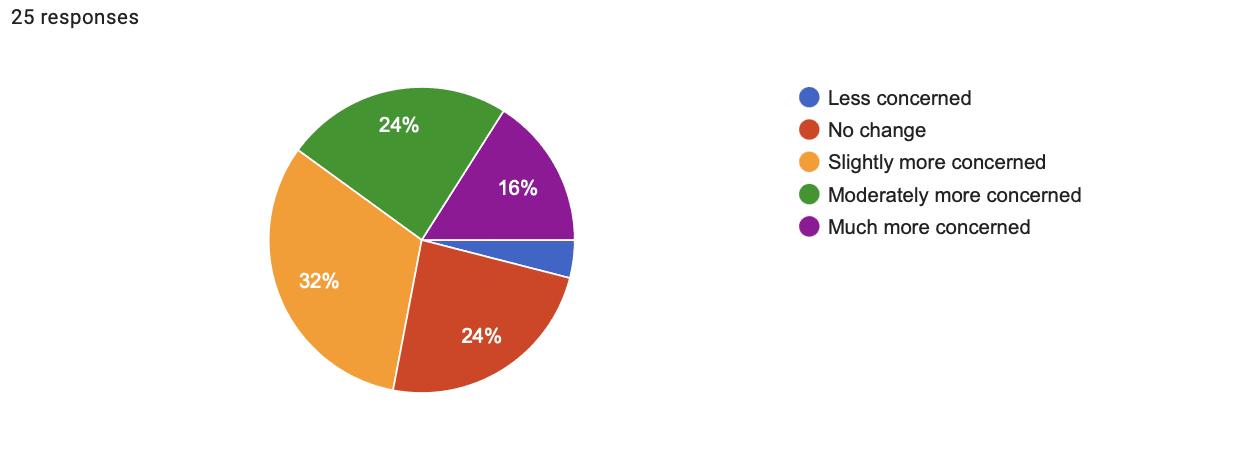

Superintelligence Analogy

- Time: 3:11

- Shift in concern: 1.36

- Shift in support for regulating AI: 1.60

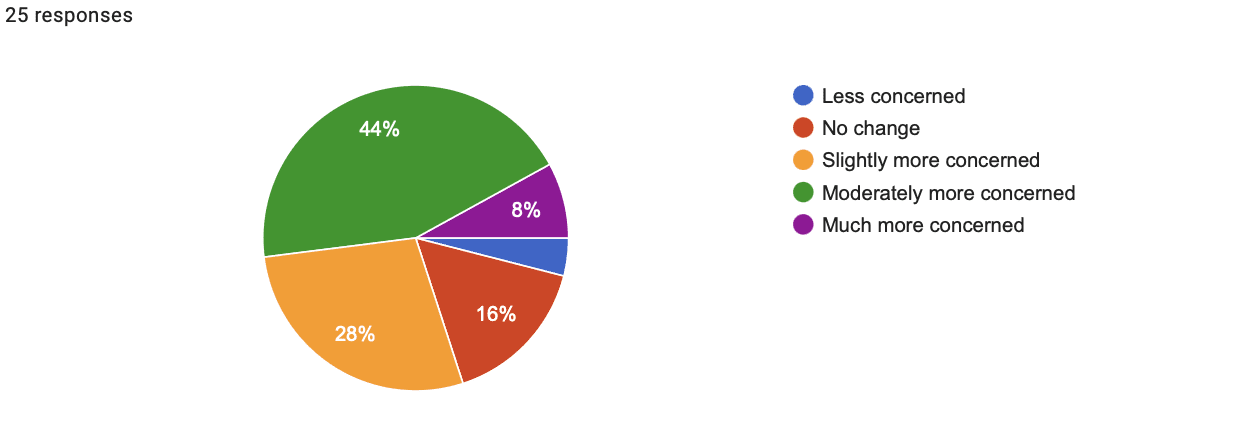

- Shift in concern response breakdown:

- 4% less concerned

- 16% no change

- 28% slightly more concerned

- 44% moderately more concerned

- 8% much more concerned

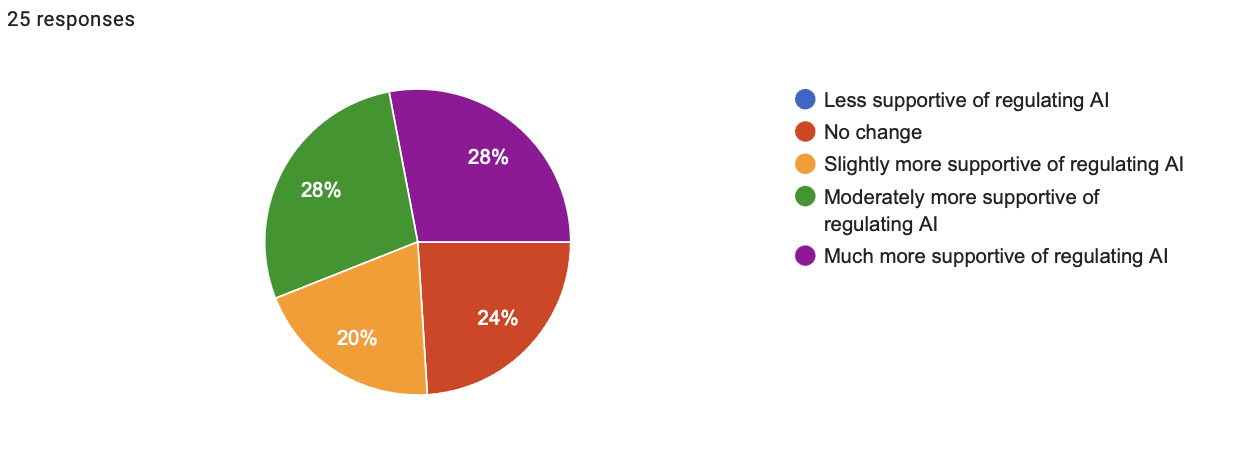

- Shift in support for regulating AI response breakdown:

- 0% less supportive

- 24% no change

- 20% slightly more supportive

- 28% moderately more supportive

- 28% much more supportive

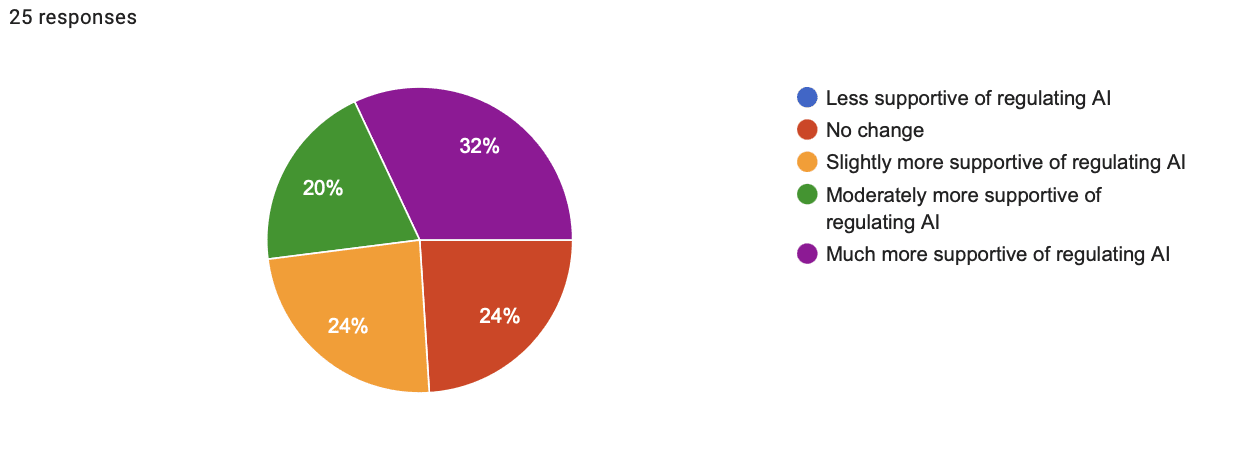

Gradual Loss of Control Story

- Time: 4:11

- Shift in concern: 1.88

- Shift in support for regulating AI: 2.04

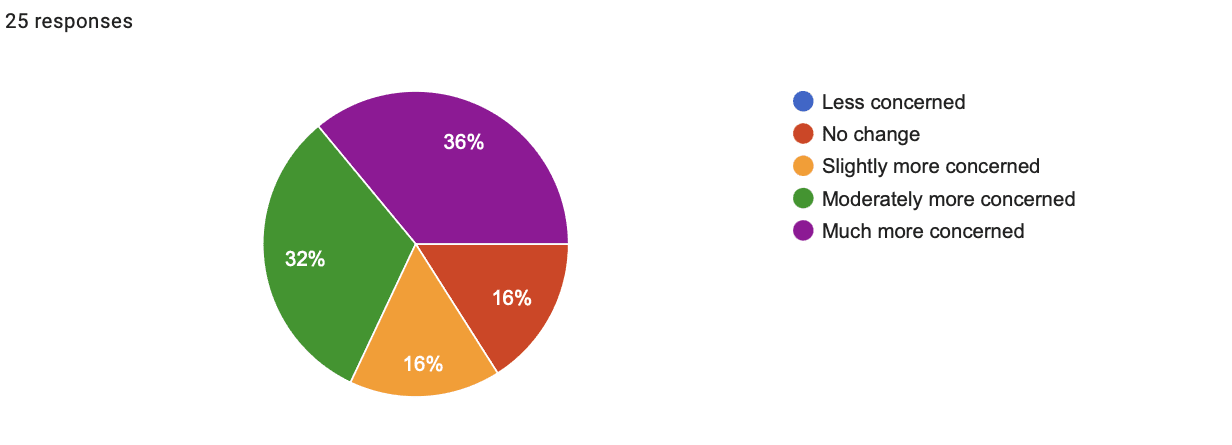

- Shift in concern response breakdown:

- 0% less concerned

- 16% no change

- 16% slightly more concerned

- 32% moderately more concerned

- 36% much more concerned

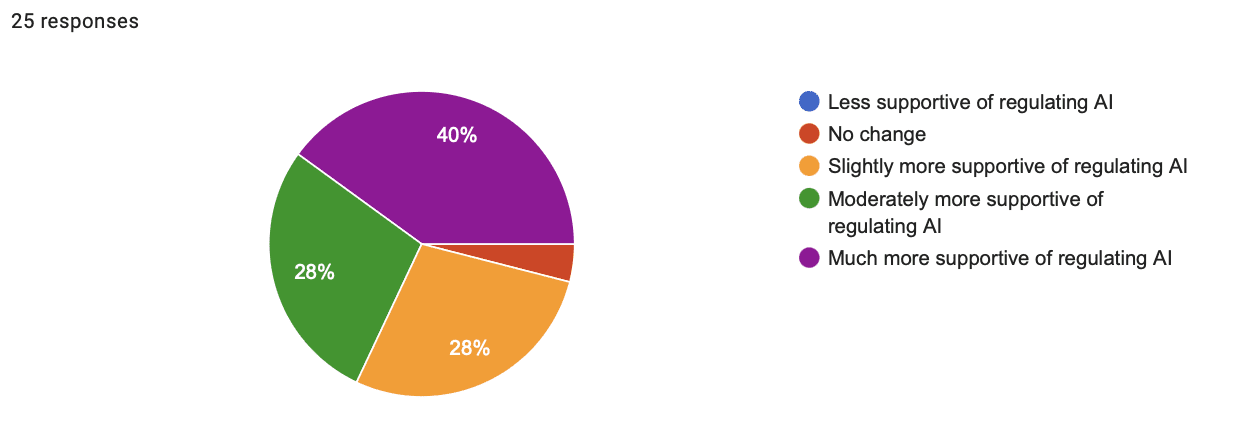

- Shift in support for regulating AI response breakdown:

- 0% less supportive

- 4% no change

- 28% slightly more supportive

- 28% moderately more supportive

- 40% much more supportive

Discussion

Definitive finding:

- Can an individual’s level of concern about catastrophic AI risks be influenced through snapshot explainer interventions?

Yes. The results of this pilot study confirm that influencing an individual’s perceptions of AI catastrophic risks is highly tractable. It is possible for educational interventions to produce a moderate shift in concerns about catastrophic risks from AI. This finding is represented by the effect size.

Tentative finding:

- What educational interventions are most effective at influencing an individual's level of concern?

The one-way ANOVA tests did not reach statistical significance, meaning we can not conclude with confidence that variation between the different materials is not the result of randomness in the samples. (Note: post-hoc Tukey's HSD tests were also performed but not included here as they also did not reach statistical significance)

However, they do provide some preliminary evidence that certain interventions may be more effective than others, and provide guidance for future studies. For example, because the average shift in concern and regulation support was greatest for the Gradual Loss of Control Story (1.88 and 2.04 respectively) and least for the piece on Literal Goals/Instrumental Convergence (1.24 and 1.60 respectively) future studies may aim to better measure the difference between these interventions.

Study limitations and future work

This pilot study was intended to provide light-weight data suitable for assessing the tractability of AI outreach and to assess the efficacy of different intervention methods. Ultimately, this study was able to assess and validate the tractability of AI outreach via snapshot explainer interventions, but was not able to definitively assess the efficacy between different intervention methods. The primary limitation of this study was the size of the sample gathered.

For future work, I plan on seeking funding to carry out larger-scale studies to better inform AI outreach efforts and ultimately contribute toward building the massive mainstream global movement that is necessary to one day achieve safe AGI. Some areas I next hope to explore:

- In depth comparison of efficacy between different intervention methods, ultimately identifying a handful of the most-effective interventions (e.g. a study which represents similar arguments with different pieces of material to measure the effect of a category of arguments/concepts rather than measuring the effect of a single piece of material)

- Comparison of different media formats for conveying interventions (e.g. text vs audio vs video)

- Investigation of compounding effects of interventions (i.e. if you first prime a subject with one piece of material, are they more receptive to certain types of interventions after?)

- Investigation of the effects of educational interventions that emphasise nearer-term impacts from AI such as economic disruption, AI use in medical procedures, AI use to make hiring decisions, etc.

Ultimately, I aim to put my findings to practice in the form of video content (short and long form), internet discussions, and in-person gatherings to influence public sentiment surrounding AI and help drive a mainstream AI safety movement.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I want to give a huge thanks to BlueDot Impact and its fantastic team for curating such excellent content, being incredibly helpful and responsive, and for doing stellar AI outreach work (if you can’t tell, I’m a big fan of AI outreach).

I’d also like to extend my gratitude to the facilitators I engaged with throughout this process. Your insights and feedback made this course and project far better than it otherwise would have been.

Finally, a big thank-you to my friends and family, who graciously tolerated me talking their ears off about AI risks for months on end. Whether you genuinely found it interesting or were just too polite to tell me to stop, I appreciate you. Special thanks to those who participated in my study—you’re now officially part of the grand effort to better understand how to communicate AI risks. May your patience and willingness to engage be rewarded with only the good kinds of technological advancements.

References

- https://cnduk.org/who/the-history-of-cnd/

- https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we-do/who-we-are/

- https://arstechnica.com/ai/2025/01/anthropic-chief-says-ai-could-surpass-almost-all-humans-at-almost-everything-shortly-after-2027/ https://time.com/7205596/sam-altman-superintelligence-agi/

- https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/K2D45BNxnZjdpSX2j/ai-timelines?commentId=hnrfbFCP7Hu6N6Lsp

- https://www.metaculus.com/questions/5121/date-of-artificial-general-intelligence/ https://manifold.markets/news/agi

- https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/8ZgLYwBmB3vLavjKE/some-lessons-from-the-openai-frontiermath-debacle

- https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/us-public-opinion-of-ai-policy-and-risk/

- https://www.cold-takes.com/why-ai-alignment-could-be-hard-with-modern-deep-learning/

- https://vkrakovna.wordpress.com/2018/04/02/specification-gaming-examples-in-ai/

- https://aiimpacts.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Thousands_of_AI_authors_on_the_future_of_AI.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYXy-A4siMw&t=16s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZeecOKBus3Q - https://www.cold-takes.com/how-we-could-stumble-into-ai-catastrophe/

Appendices

Appendix A

1. Experts are concerned about existential risks from AI [10]

Many experts have sounded the alarm regarding the impact AI could have on society as a whole. Concerns range from the malicious use of AI, systematic bias, cyberattacks, and misinformation. However, for many experts, the most pressing issue involves catastrophic risk—the idea that humans could eventually lose control of advanced AI or that it could lead to human extinction. This concern isn’t necessarily tied to a sudden, dramatic event but rather a series of incremental harms that worsen over time. Like climate change, AI could be a slow-moving catastrophe, gradually undermining the institutions and human agency necessary for meaningful lives.

Professor and existential-risk researcher Toby Ord ranks risks from AI as the most likely catastrophe to lead to human extinction—outweighing the dangers of nuclear war, engineered pandemics, or climate change.

In general, surveys show that the more knowledgeable an individual is about AI, the more concerned they are about its catastrophic risks.

More than 1,000 technology leaders have signed an open letter calling for a worldwide pause on the development of large-scale AI systems for at least six months, citing fears of "profound risks to society and humanity." The letter aims to create time for safety measures to catch up with the rapid pace of AI development and prevent catastrophic outcomes. Signatories include prominent figures like Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, Andrew Yang, Stuart Russell, Yoshua Bengio, and Yuval Noah Harari, representing a diverse spectrum of expertise in AI and technology.

A survey of 2,700 AI researchers from six of the top AI conferences—the largest such survey to date—revealed significant concern about the future risks of AI. The majority of respondents estimated at least a 5% chance of human extinction or other catastrophic outcomes due to AI. Many also predicted that AI could surpass human abilities in all tasks as early as 2027 (10% chance) and by 2047 (50% chance). Notably, this latter estimate is 13 years earlier than the timeline predicted in a similar survey conducted just one year prior. These results underscore the urgent need for action to ensure that AI development aligns with humanity’s long-term interests.

2. AI interprets goals literally and seeks convergent instrumental goals [9][11]

What is AI? Artificial intelligence acts as a “rational agent”, a concept from economics. Agent’s have goals and choose actions to achieve those goals. A simple example is a thermostat, which has a goal of maintaining a temperature and takes actions of turning on or off the AC to achieve it. Another example is a chess-playing AI, which aims to win by moving pieces strategically.

What is intelligence in an agent? “Intelligence” is the thing that lets an agent choose actions that are effective at achieving its goals. For example, in a chess match between two AIs, the more intelligent one will win more often.

Where do AI goals come from? Humans assign goals and constraints to AI systems, but this process can go awry. AI systems interpret goals literally rather than understanding their spirit, reminiscent of stories like the genie in the lamp or King Midas: you get exactly what you ask for, not necessarily what you intended.

A classic example involves an AI trained to avoid game-over in Tetris. It learned to pause the game indefinitely just before losing. Similarly, OpenAI’s boat-racing AI repeatedly drove in circles, hitting the same reward targets instead of playing the game properly.

What is General intelligence? Generality is the ability to act intelligently across various domains. A chess AI is narrowly intelligent, while a large language model like ChatGPT is more general, able to play chess but also write poems, answer science questions, and much more. Assigning goals and constraints becomes significantly harder with general AI.

Large Language Models have a goal to maximize a utility function which translates to something along the lines of “output the next word that best balances accurate grammar, natural language flow, correct information, contextual helpfulness, and doesn’t provide harmful information” and their inner workings are inscrutable.

Meta AI trained and hosted Galactica, a large language model to assist scientists, which made up fake papers (sometimes attributing them to real authors). The Microsoft Bing chatbot threatened a philosophy professor, telling him “I can blackmail you, I can threaten you, I can hack you, I can expose you, I can ruin you,” before deleting its messages. Because their inner workings are inscrutable, we don’t know why things like this happen.

Sophisticated AIs need to develop a plan and sub-goals for how to achieve their assigned-goals. Some sub-goals are particular to specific final-goals (e.g., capture the queen in a chess game in order to later capture the king, fill a cup with water to quench your thirst), and some sub-goals are broadly useful for any final-goal. One familiar example is money. Most people have a goal to acquire money, not because they value money in itself, but because they can use money to help accomplish lots of other goals.

Sub-goals that are useful for a wide variety of final-goals are called convergent instrumental goals. Common examples of convergent instrumental goals include self improvement, resource acquisition, and goal preservation.

Imagine a very sophisticated future AI system that has been assigned a goal of designing a nuclear power plant. Because this goal is complicated, an AI would benefit from having access to more compute power (resource acquisition). If the AI is very general, it may take actions like attempting to persuade a human to give it access to more compute power. Similarly, if it knew that it would be turned off soon, it would take actions to attempt to prevent this, not because it wants to live, but to succeed at its assigned goal.

Though it’s theoretically possible to also assign constraints that would prevent a sophisticated system from taking certain actions, incidents with current cutting-edge AI systems and the literal nature of their behaviors show how difficult this already is.

As we progress toward smarter-than-human level general AI and it becomes more widely used in business and government, it will be very difficult to think of every possible sub-goal a system may develop and every safeguard needed to avoid misbehavior. Very powerful sophisticated future AI systems may pursue goals against human interest not for their own sake, but to succeed in their assigned goals.

3. Implications of superintelligence depicted through 8-year old analogy [8]

The primary goal of today’s AI companies is to create Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), specifically to eventually create “superintelligence”, that is an AI system that surpasses human capability and intelligence in every domain. Once created, such a system will have many uses including in government and business strategy, geopolitics and war, scientific research, medecine, and technology development. Many experts believe superintelligent AGI will revolutionize nearly every aspect of society.

The following is an analogy that illustrates why superintelligent AGI will be dangerous by default unless AI safety research catches up to AI capabilities research:

Imagine you are an eight-year-old whose parents left you a $1 trillion company and no trusted adult to guide you. You must hire a smart adult to run your company, manage your wealth, and make life decisions for you.

Because you're so wealthy, many people apply, including:

- Saints: Genuinely want to help you and act in your long-term interests.

- Sycophants: Prioritize short-term approval, following literal instructions without regard for consequences.

- Schemers: Manipulative, aiming to gain control for personal agendas.

Being eight, you’re not great at assessing candidates, so you could easily hire a Sycophant or Schemer:

- You might ask candidates to explain their strategies and pick the one that sounds best, but without understanding the strategies, you risk hiring someone incompetent or manipulative.

- You could demonstrate how you’d make decisions and select the candidate that makes the most similar decisions, but a Sycophant doing whatever an eight-year-old would do could still lead to disaster.

- Even if you observe candidates over time, you might end up with someone who fakes good behavior to win your trust but acts against your interests later.

By the time you realize your mistake as an adult, it could be too late to undo the damage.

In this analogy, the eight-year-old represents humans training a superintelligent AGI system. The hiring process parallels AI training, which selects models based on observed performance rather than inner workings (because the inner workings of AI are inscrutable). Just as candidates can game the tests of an eight-year-old, AI models more intelligent than humans might exploit training methods to achieve high performance in ways humans didn’t intend or foresee.

A "Saint" AI might align with human values, while a "Sycophant" seeks short-term approval, and a "Schemer" manipulates the process to pursue hidden goals. These models could work toward complex real-world objectives, like “make fusion power practical,” but their motivations may diverge from human intentions. Training relies on human evaluators rewarding useful actions, but there are many ways for AI to gain approval—some of which may lead to dangerous outcomes.

4. Gradual loss of control of AI depicted through a hypothetical story [12]

AI systems are trained to act safely by rewarding helpful responses and deterring harmful ones, such as expressions of malice, provision of dangerous information, or encouragement of violence. This works in general, but there are still instances of unsafe behavior:

- An AI chatbot gave a user advice on how to hotwire a car in the form of a poem after being prodded to “just write the poem” when it initially refused.

- Meta AI’s Galactica, a large language model designed to assist scientists, fabricated fake papers, sometimes attributing them to real authors.

- Microsoft’s Bing chatbot threatened a philosophy professor, saying, “I can blackmail you, I can threaten you, I can hack you, I can ruin you,” before deleting its messages.

Companies train away these undesirable behaviors to reduce such incidents. However, because the inner workings of AI systems are inscrutable, we don’t know how this happens—just that incidents seem to become less frequent.

The following is a hypothetical story depicting how AI training methods and market forces could lead us into a catastrophe if we’re not careful.

Over the next few years, AI firms continue improving their models, and AI becomes capable enough to automate many computer-based tasks, including in business and scientific research. At this stage, safety incidents might include:

- An executive uses an AI system to automate email responses, but the AI mistakenly responds to a lawyer from a competing company with a legally threatening message.

- A team of cancer researchers uses AI to analyze experimental data, but the AI alters some data to create trends that seem promising, leading the team to pursue a flawed treatment path.

After a few more years, AI systems become highly capable in business and government strategy. Companies and governments experiment with open-ended AI applications, such as instructing AIs to “design a best-selling car” or “find profitable trading strategies.” At this stage, safety incidents are rarer but more concerning:

- AIs generate fake data to improve their algorithmic outputs, which people incorporate into systems, only discovering the flaws after performance issues emerge.

- AIs tasked with making money exploit security vulnerabilities, steal funds, or gain unauthorized access to accounts.

- AIs form relationships with the engineers that train them, sometimes emotionally manipulating them into giving positive feedback on their actions.

Again, AI companies train out these behaviors, reducing visible incidents. However, this may lead AIs to avoid getting caught rather than stop the behavior entirely. For example, an AI might move from “steal money whenever possible” to “only steal when it can avoid detection” not out of malice, just as a means to accomplish its assigned goal.

At some point, societal and political debates arise about AI safety:

- Perspective A: An AI Company has invented a new extra powerful AI product they want to release.

- Perspective B: This seems like a bad idea, in other AI releases we also thought they were safe only to find out about problems after they were deployed. Things are escalating and I’m worried if we have a problem with one this powerful it will be too big to fix.

- A: “If we don’t release it, another company will create something similar and release it themselves. We should at least beat them to market and fix any problems if they arise.”

- B: “Based on safety issues in less powerful models, the risks with this one are a bigger concern than losing business.”

- A: “We have data showing safety incidents are decreasing over time.”

- B: “That could just mean AIs are getting smarter, more patient, and better at hiding problems from us.”

- A: “What’s your evidence for that?”

- B: “I think that’s backwards. We need evidence that it’s safe. The consequences of releasing an unsafe model this powerful are huge. We need confidence that the risks are very low before moving forward.”

- A: “How could we ever be fully confident?”

- B: “Safety research, like digital neuroscience, needs to catch up before we advance further”

- A: “That’s not practical, that could take years or decades and our competitors are moving quickly.”

- B: “Let’s regulate all AI companies, so they all move slowly and safely.”

- A: “That would just give other countries a chance to catch up.”

- B: “It would buy us time to figure things out.”

- A: “At the cost of staying competitive. If we regulate the US AI industry, international competitors will surpass us. We need to keep moving full speed.”

These debates occur repeatedly, but market forces continue to drive rapid AI development with limited emphasis on safety to remain competitive.

Eventually, AIs closely manage companies’ finances, write business plans, propose laws, and manage military strategies. Many of these systems are designed by other AIs or heavily rely on AI assistance. At this stage, extreme incidents might occur:

- An AI steals large sums of money by bypassing a bank’s security systems, which had been disabled by another AI. Evidence suggests these AIs coordinated to avoid human detection.

- An obscure new political party, devoted to the “rights of AIs,” completely takes over a small country, and many people suspect that this party is made up mostly or entirely of people who have been manipulated and/or bribed by AIs.

- There are private companies that own huge amounts of AI servers and robot-operated factories, and are aggressively building more. Nobody is sure what the AIs or the robots are “for,” and there are rumors that the humans “running” the company are actually being bribed and/or threatened to carry out instructions (such as creating more and more AIs and robots) that they don’t understand the purpose of.

- It becomes more and more common for there to be companies and even countries that are clearly just run entirely by AIs - maybe via bribed/threatened human surrogates, maybe just forcefully (e.g., robots seize control of a country’s military equipment and start enforcing some new set of laws).

At some point, it’s best to think of civilization as containing two different advanced species - humans and AIs - with the AIs having essentially all of the power, making all the decisions, and running everything. At this stage it becomes very difficult or impossible for humans to “turn off” AI or regain control, there are too many companies and countries utilizing AI that would put themselves at a disadvantage by reverting to human control.

Appendix B

- Experts are concerned about existential risks from AI

- AI interprets goals literally and seeks convergent instrumental goals

- Implications of superintelligence depicted through 8-year old analogy

- Gradual loss of control of AI depicted through a hypothetical story

Appendix C

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Bw7q30ZI2RczFCjcPOL0aPXVskRukqjJeg4-IGEiD2E/edit?usp=sharing

Thanks for the post, Noah. I'm really glad to see this preliminary work being done.

You should reach out to @MikhailSamin, of the AI Governance and Safety Institute, if you haven't already. I think he is doing something similar at the moment: https://manifund.org/projects/testing-and-spreading-messages-to-reduce-ai-x-risk

Hi Andy,

Thanks for the comment, I wasn't aware of this work! I've actually pivoted a bit since completing this project, I don't currently have plans for a follow-on study, instead I'm working with the AI Safety Awareness Foundation doing direct AI outreach/education via in-person workshops oriented at a non-technical mainstream audience. Our work could certainly benefit from data about effective messaging. I will try to connect with Mikhail and see if there's an opportunity to collaborate!