The following is a condensed version of Faunalytics’ original study, which can be read in full (including a summary and key takeaways) here.

Introduction

Animals used for food generally receive significantly less attention and funding than companion animals (Faunalytics, 2019). Small-bodied animals like chickens and fish are killed in particularly massive numbers—there are over 12 times more chickens killed each year than cows, and over 3,000 times more fish killed than cows (Faunalytics, 2020; Sentient Media, 2018; The Economist, 2011).

The current study was created to help answer important questions regarding these animals: which beliefs do the U.S. public have about small-bodied animals, and which of these are associated with animal-positive behaviors? Specifically, we looked at how a number of beliefs related to both a willingness to sign a petition to reduce the suffering of each animal and a diet pledge to reduce the consumption of each. We believe that by answering these questions, advocacy efforts can become more targeted and effective.

This project was completed by Tom Beggs and Jo Anderson of Faunalytics. Thanks to Thomas Billington and Haven King-Nobles from the Fish Welfare Initiative, Susanna Lybæk from the Norwegian Animal Protection Alliance, and Yip Fai Tse from Mercy For Animals for their feedback.

Methods Overview

Below is a summary of our methods for the analysis. Full procedural details and the survey instrument are available on our project page on the OSF.

We began by asking advocates working in the small-bodied animal space what beliefs they think people hold about fish and chickens. In addition, we surveyed the general public and asked them to tell us their own beliefs about either chickens or fish (n = 126; recruited through Positly). From these two sources, we compiled a list of possible beliefs for inclusion in the main study. We organized the list into themes and selected what we thought were the most common and important beliefs for each—a total of 33 beliefs for fish and 32 beliefs for chickens.

We then surveyed 1,073 U.S. adults and randomly assigned them to either the chicken or fish version of the survey. We asked them how much they agreed or disagreed with each of the beliefs for their assigned animal.

There were two outcome measures to get a sense of how each belief was associated with pro-animal behaviors. In the “diet pledge” outcome measure, each participant was asked whether they would pledge to reduce their consumption of the respective animal. For example, those in the fish condition were asked “In recent years, many people have begun to reduce how much fish they eat, a pattern that is expected to continue. Will you pledge to reduce your own fish consumption?” If they agreed, they specified the amount they would limit themselves to and provided a digital signature.

In the “petition” outcome measure, participants were asked whether they were willing to sign a petition supporting better welfare for the animal in question. For example, people who completed the chicken survey were asked “We would like to give you the opportunity to sign a petition that would encourage legal reforms to improve the lives of farmed chickens. Specifically, the petition is designed to build support for regulations that would ensure that chickens raised on farms would have improved living and slaughter conditions. Would you be willing to sign this petition?” Participants could select either “yes please” or “no thanks” in response.

These were presented at the end of the survey, where we thanked participants for their answers. We made it clear to participants that their participation incentive did not rely on them signing either the diet pledge or the petition. The two outcome measures were counterbalanced, meaning that half the participants saw the petition first, and the other half saw the pledge first.

Results

As noted at the beginning of this post, I have included only some of our findings below. To view our results in full (including an assessment of demographic differences in the data), visit the complete study on Faunalytics’ website.

As a further note, because of the large sample size, many of the correlations were statistically significant. We recommend looking at the size of the correlation and the error bars to help understand differences between individual beliefs. For figures with error bars, the bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

How Many People Took The Pledge And Signed The Petition?

30% of participants took the diet pledge to reduce their consumption of fish, and 31% agreed to reduce their consumption of chicken. 37% of participants agreed to sign the fish welfare petition, and 40% agreed to sign the chicken welfare petition. More specifically, of fish pledge-takers, 18% pledged to never eat fish, 72% pledged to eat it less than once a week, and 11% pledged to eat it 1-3 times a week. Of chicken pledge-takers, 8% pledged never to eat chicken, 60% pledged to eat it less than once a week, and 31% pledged to eat it only 1-3 times a week.

The Most Common Beliefs About Fish & Chickens

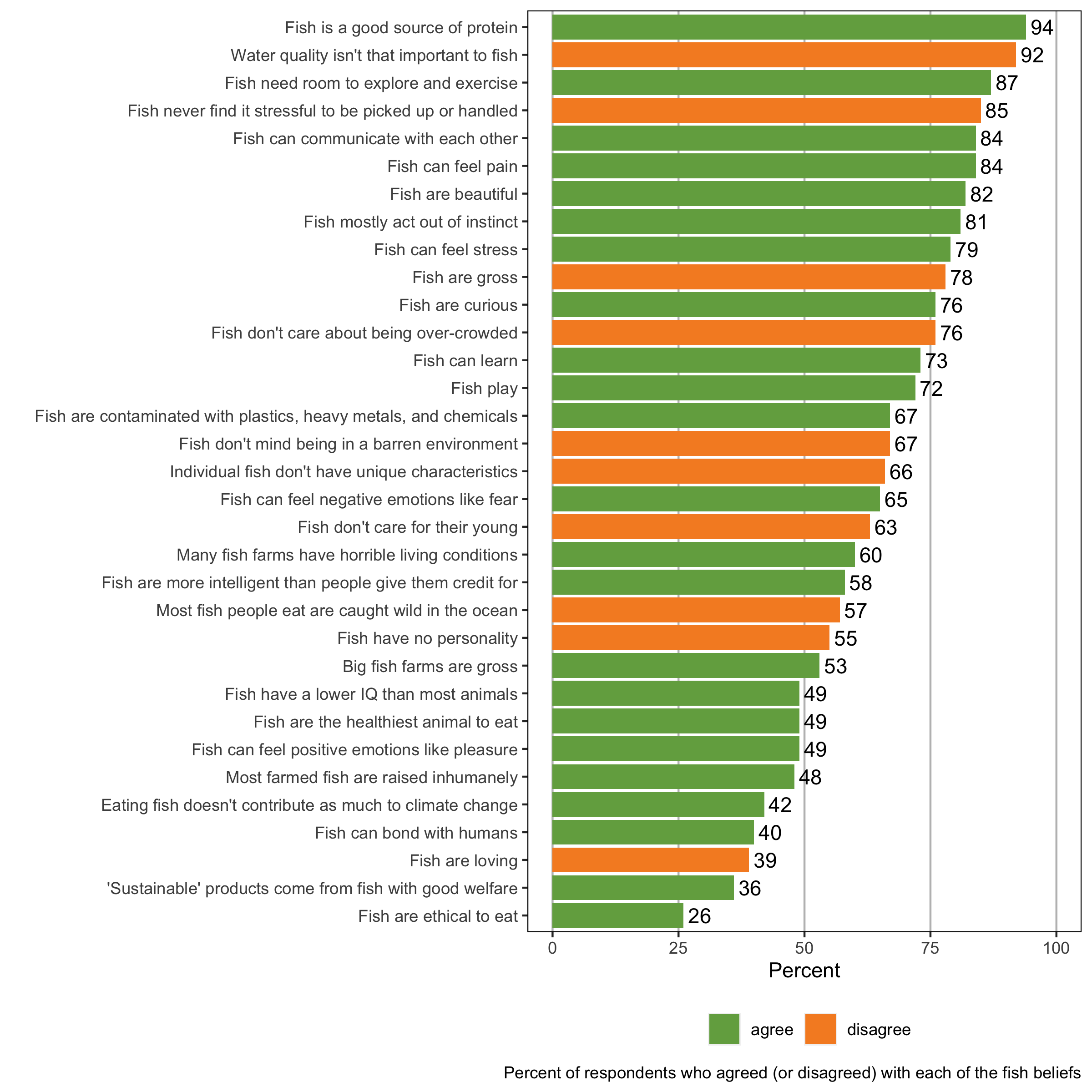

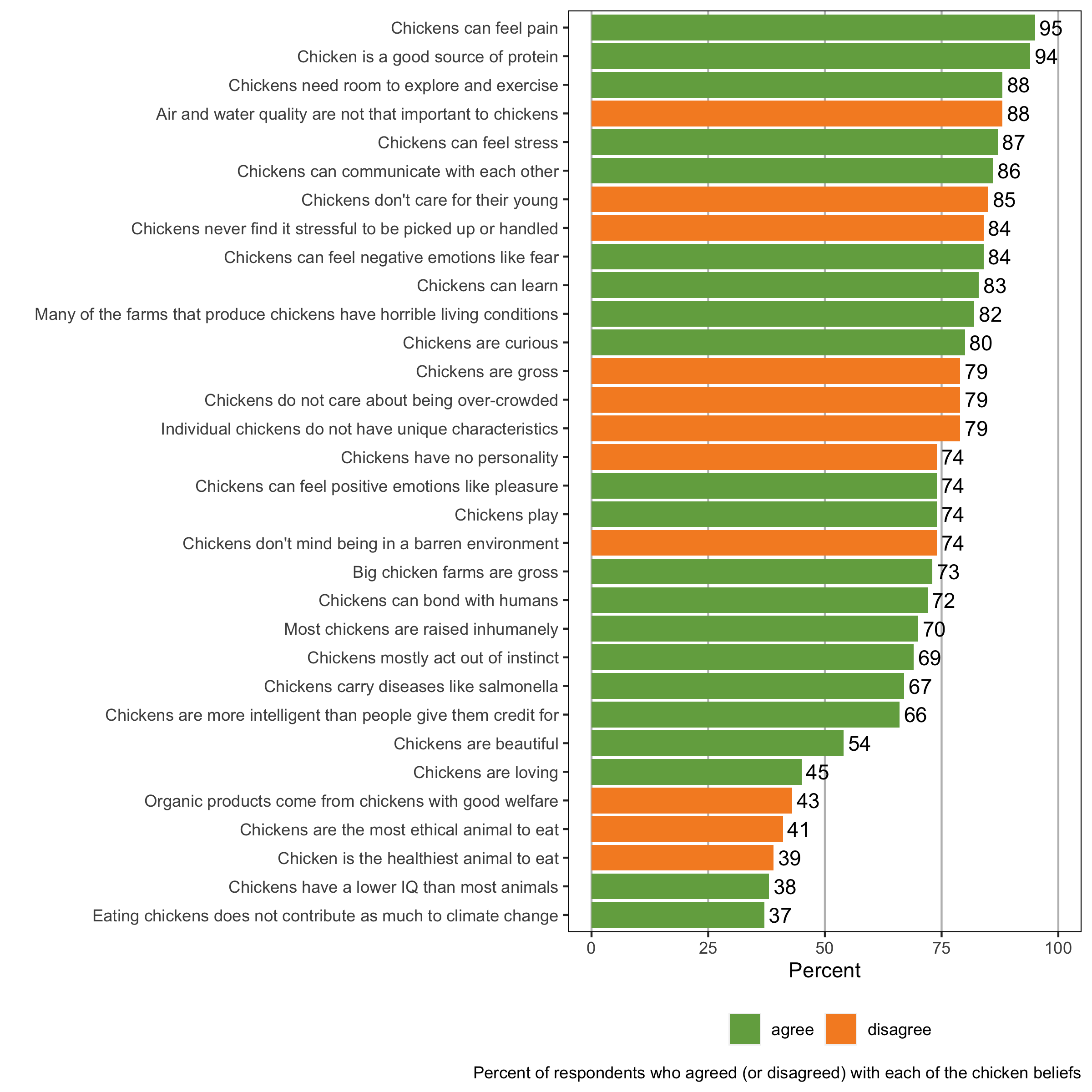

The following figures show all of the beliefs included in the study and the proportion of people who either agreed or disagreed with each. This gives a sense of how common each of the beliefs are, which can be helpful in deciding which beliefs already exist and can be tapped into, and which beliefs need to be encouraged.

Figure 1: Beliefs About Fish

Figure 2: Beliefs About Chickens

Which Categories Of Beliefs Were Most Strongly Associated With Animal-Positive Behaviors?

Each individual belief is presented in the figures below, in groups of conceptually similar beliefs for each animal. The relative importance of each item within each group of beliefs can be seen for both petition signatures and diet pledges. We also discuss the top-performing individual beliefs across the categories. In general, average correlations for the beliefs in each category were small (< .20), with beliefs generally showing larger correlations with diet pledges than with petition signatures.

Beliefs About Fish

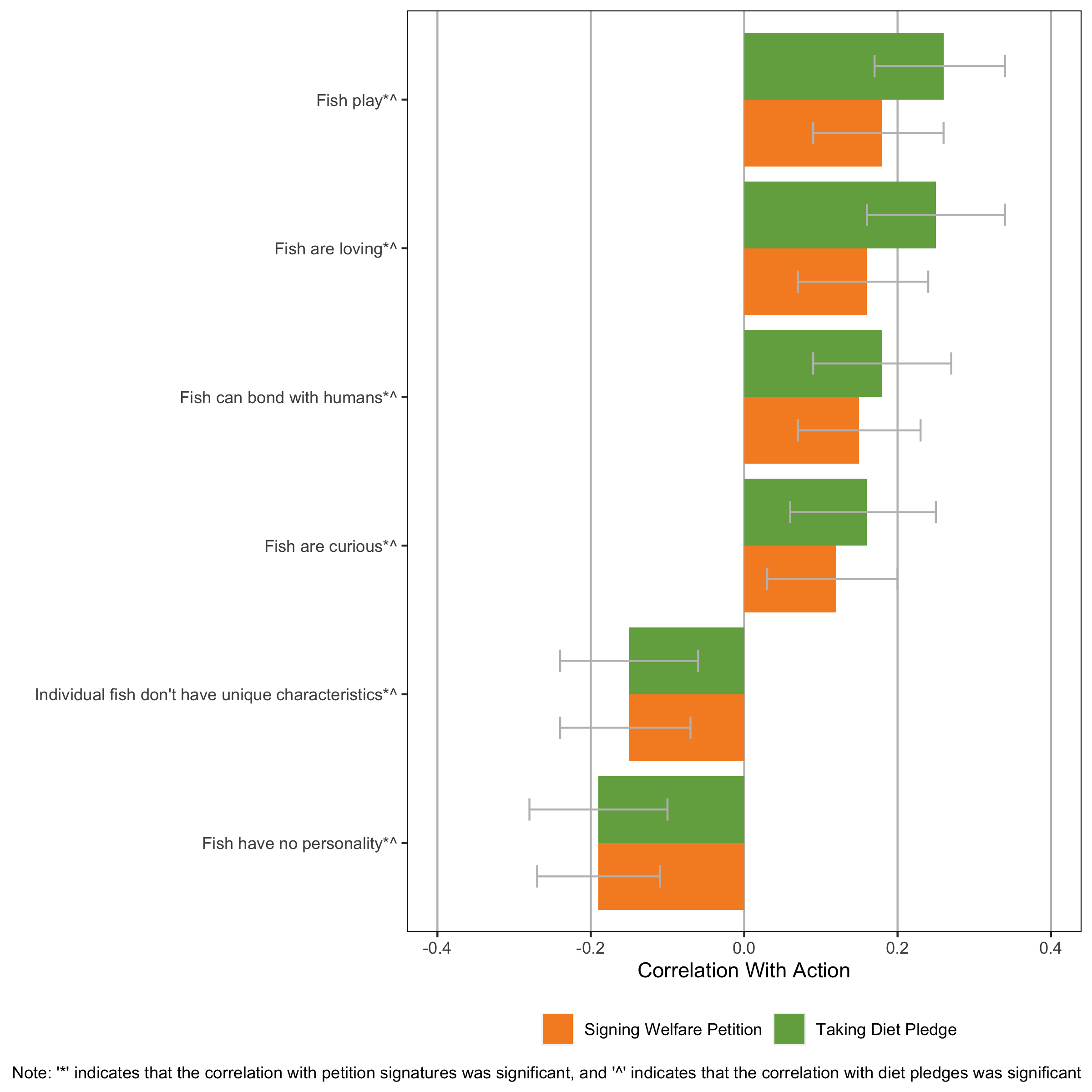

Fish Personality Beliefs

Fish personality beliefs showed the largest average correlation with signing the diet pledge of all the categories of beliefs (r = .20, SD = .05) and had the second-strongest correlation with petition signatures (r = .16, SD = .03). In other words, people who believe that fish have personality traits were more likely to take the diet pledge and sign the petition.

Looking at particularly strong individual items for both outcomes, people who believe that fish play and that they are loving were more likely to take diet pledges, while those who agreed with the idea that fish have no personality were less likely to sign the petition.

Figure 3: Fish Personality Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

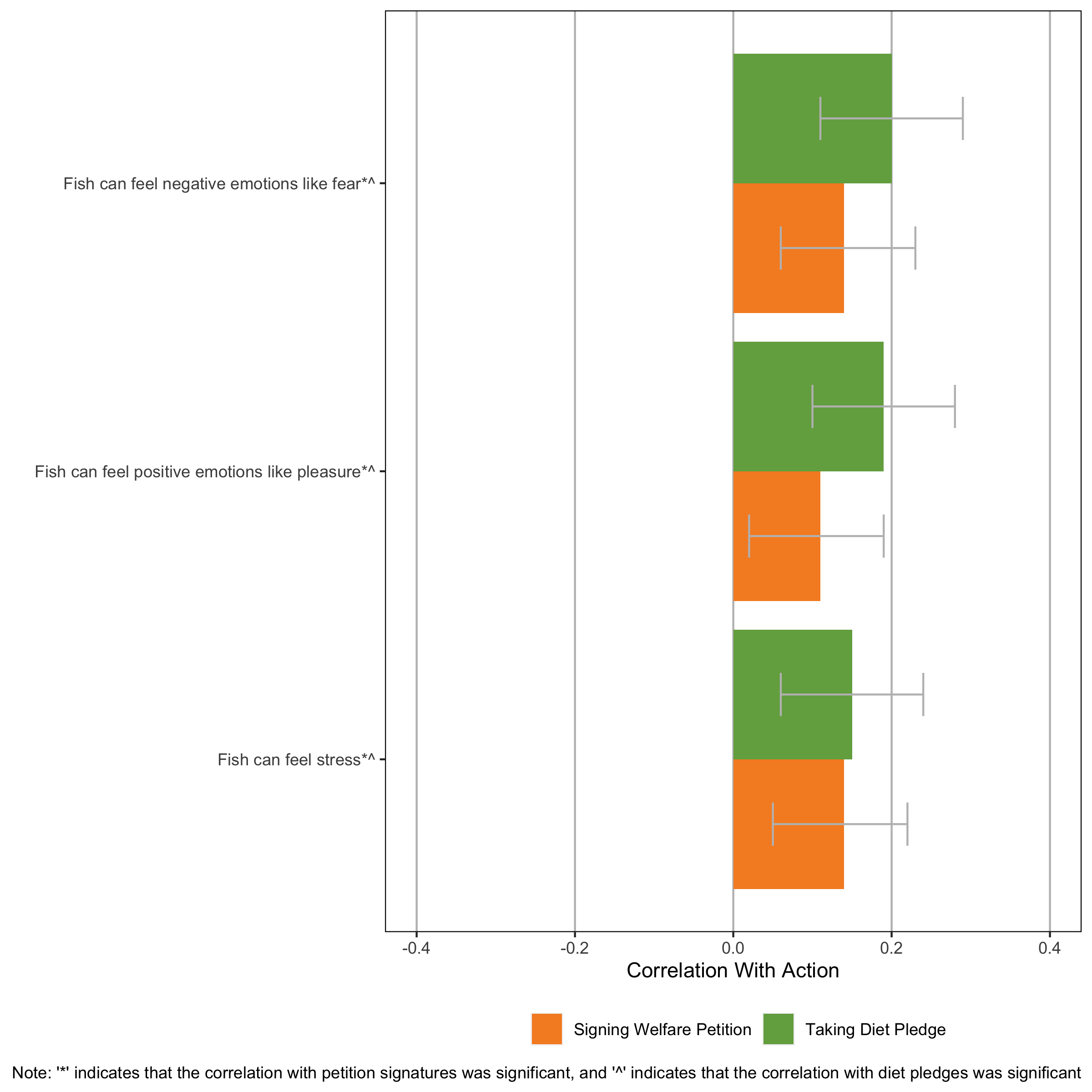

Fish Emotion Beliefs

Beliefs around fish emotions had the second-largest average correlation with signing the diet pledge (r = .18, SD = .03) and the third-largest average correlation with petition signatures (r = .13, SD = .02). People who believe that fish have emotions were more likely to take the diet pledge and sign the petition. That said, no individual items in the emotion category were particularly strong when compared to beliefs across all categories. However, the category as a whole performed well and consistently, and should likely be considered in advocacy efforts.

Figure 4: Fish Emotion Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

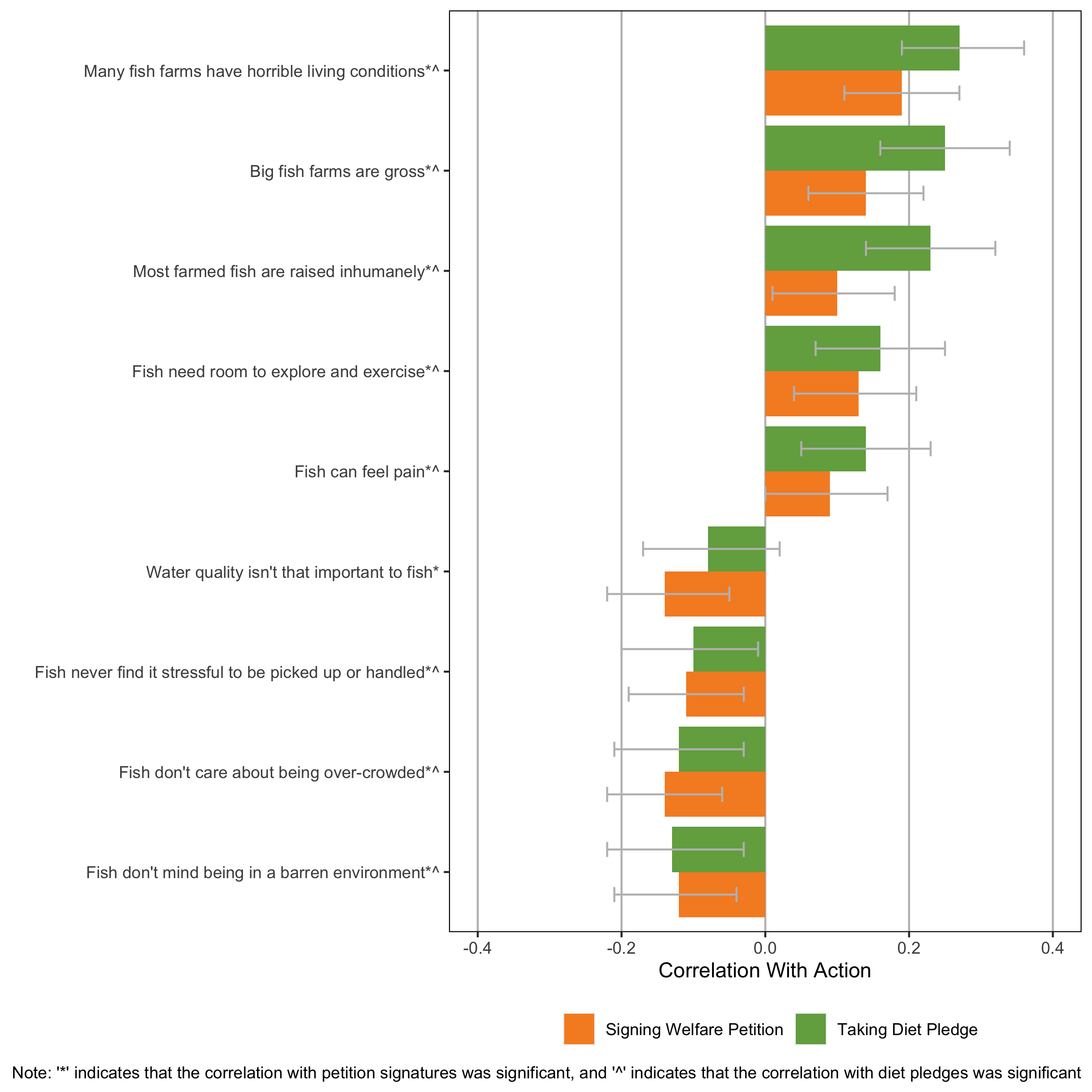

Fish Suffering Beliefs

Beliefs around fish suffering had a good association with fish-positive behavior. Despite a large number of items in the category, it had the third-largest average correlation with the diet pledge (r = .16, SD = .07) and the fourth-largest association with petition signatures (r = .13, SD = .03). The belief that fish farms have horrible conditions was particularly strong—people who agreed were more likely to take the diet pledge and sign the petition.

This finding supports the common advocacy tactic of presenting information about farm conditions. Themes around grossness and inhumane treatment were also strong performers for diet pledges, while overcrowding and water quality performed well for petition signatures.

Figure 5: Fish Suffering Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

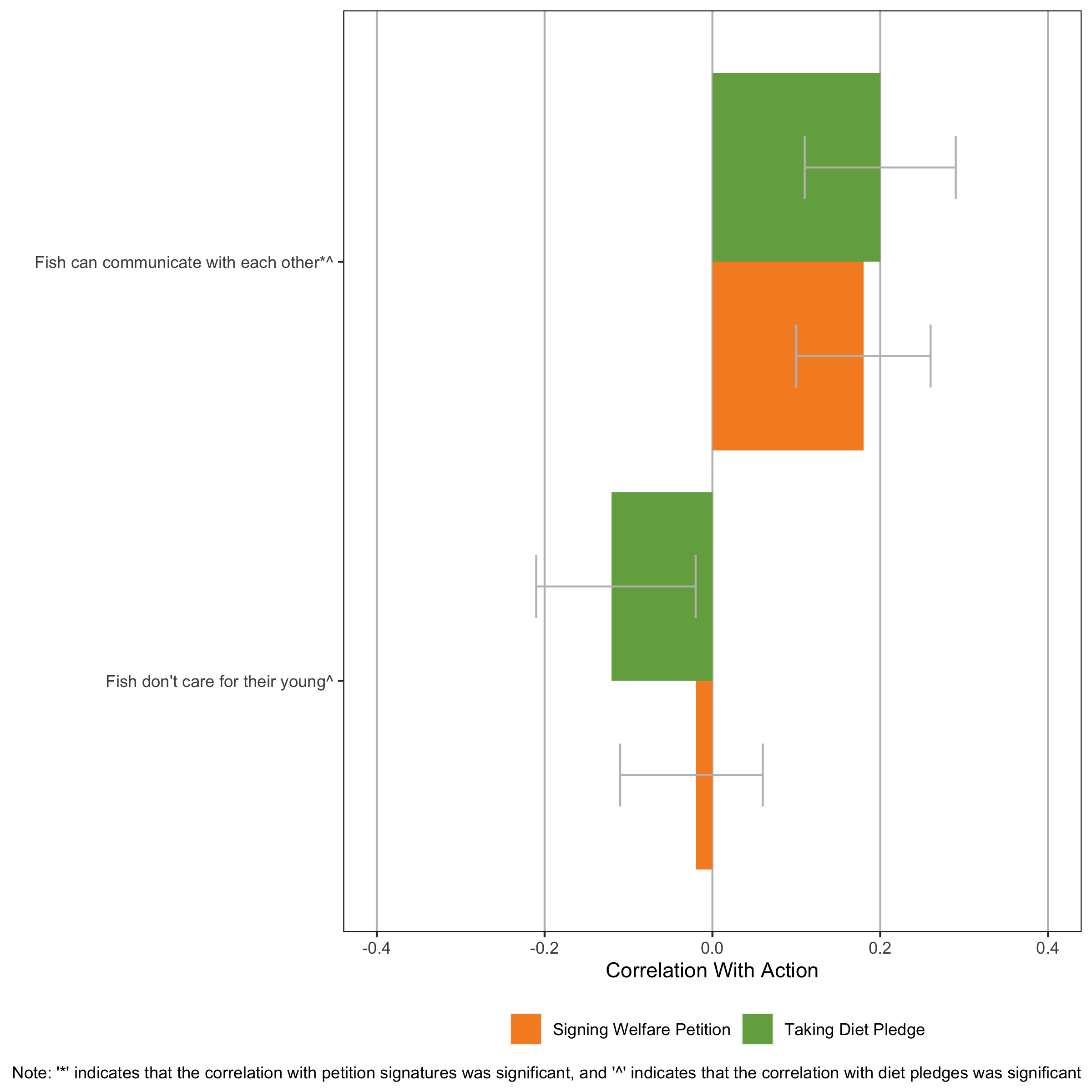

Fish Social Beliefs

Fish social beliefs had the fourth-largest average association with dietary pledges (r = .16, SD = .06) and the sixth-largest association with petition signatures (r = .10, SD = .11). The belief that fish can communicate was one of the most important individual beliefs in terms of the association with petition signatures—those who agreed were more likely to sign the petition.

Figure 6: Fish Social Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

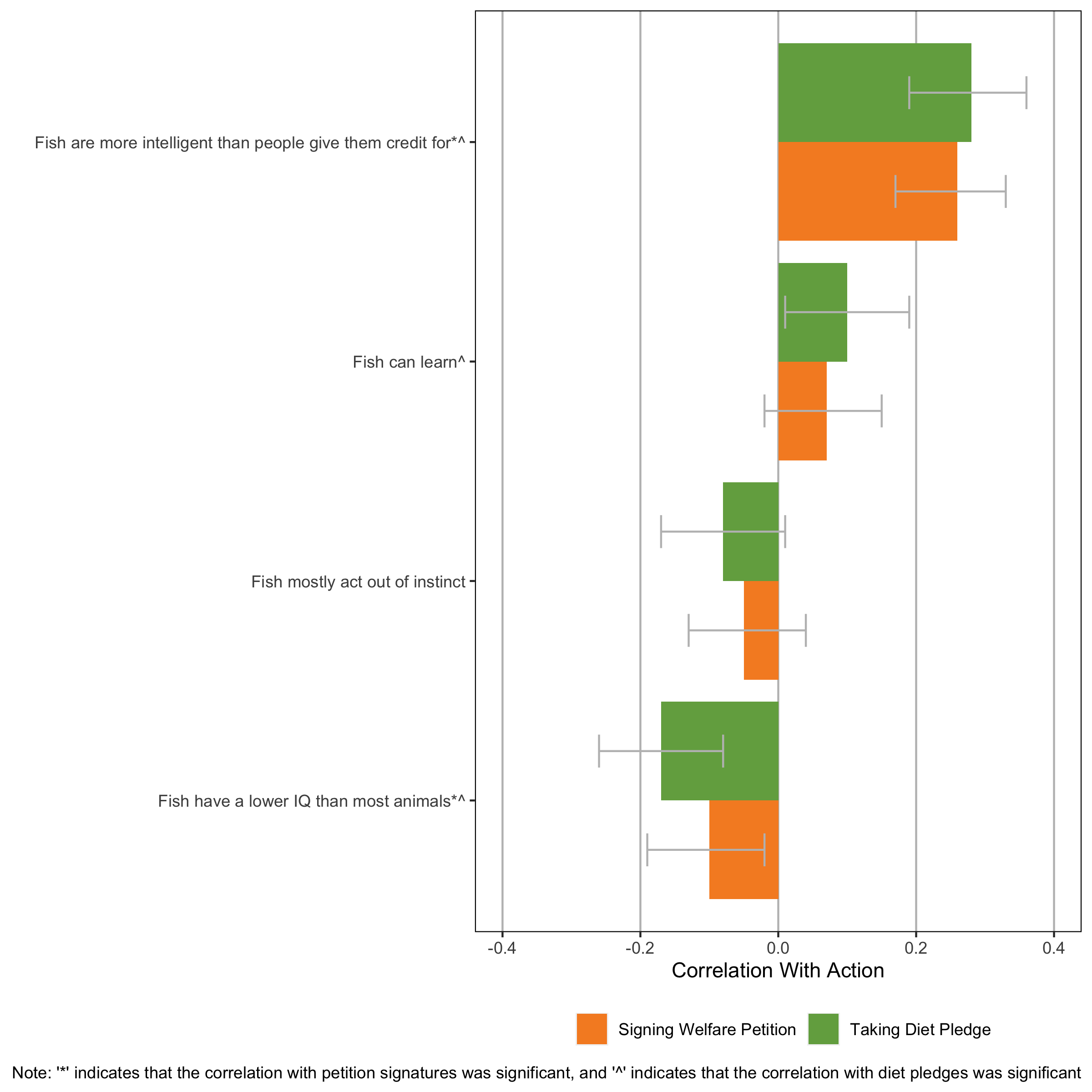

Fish Intelligence Beliefs

Fish intelligence beliefs had the fifth-strongest association with diet pledges (r = .16, SD = .09) and petition signatures (r = .12, SD = .10) on average. One item stood out from the rest—the belief that fish are more intelligent than people give them credit for. This item had the highest correlation of any individual belief in all categories for both diet pledges and petition signatures. Those who hold this belief were more likely to show both animal-positive behaviors in our study.

Figure 7: Fish Intelligence Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

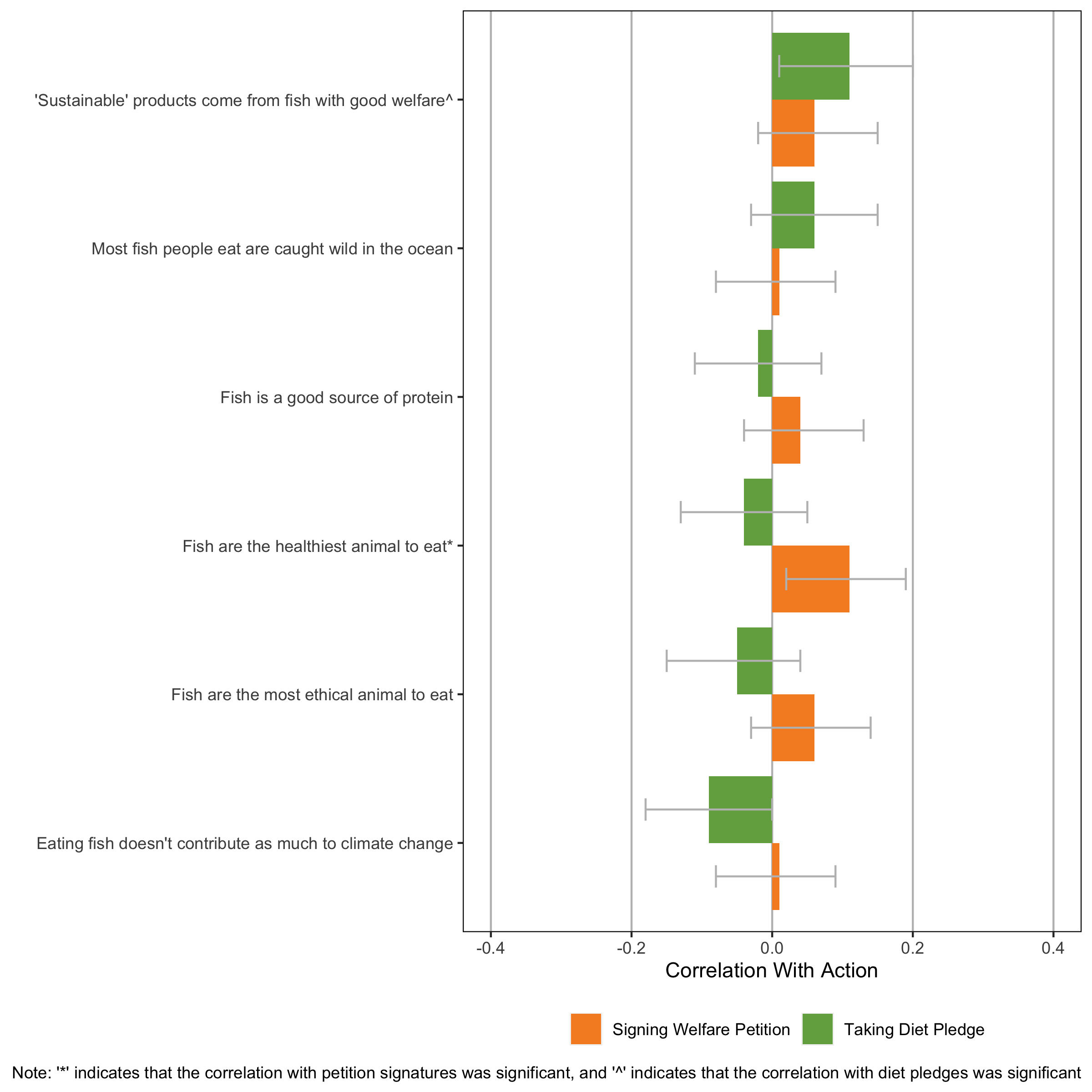

Fish Consumption Beliefs

Beliefs relating to fish as food had the weakest performance of all of the categories of belief for both diet pledges (r = .06, SD = .03) and petition signatures (r = .05, SD = .04). No individual items particularly stood out when compared to other items across categories.

Figure 8: Fish Consumption Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

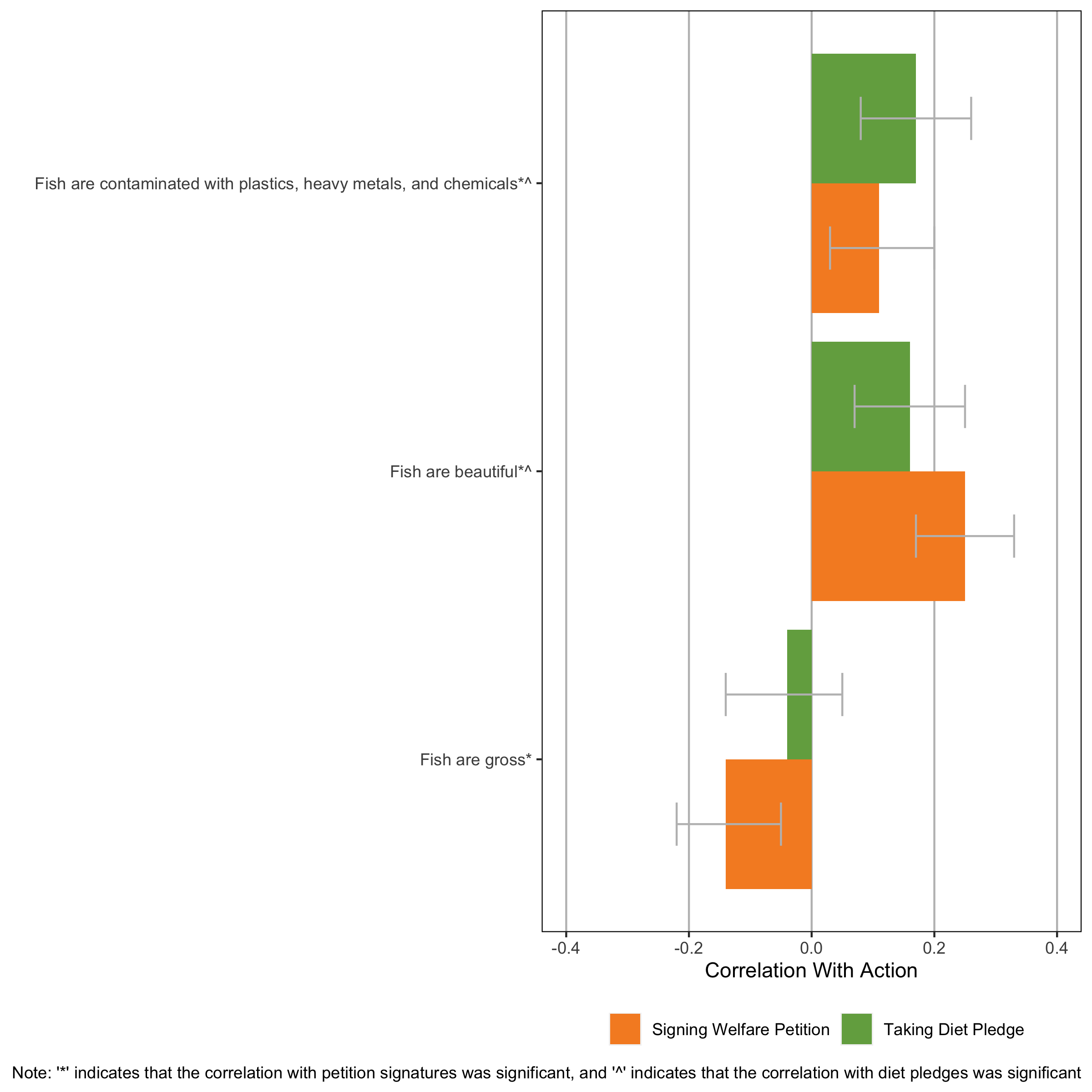

Other Fish Beliefs

“Other” fish beliefs had only the sixth-largest average correlation with diet pledges (r = .12, SD = .07), but the largest average correlation with petition signatures (r = .17, SD = .07). This top category ranking for petition signatures was due in large part to the strong performance of the belief that fish are beautiful, which was one of the best performers in any category.

Figure 9: Other Fish Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

Beliefs About Chickens

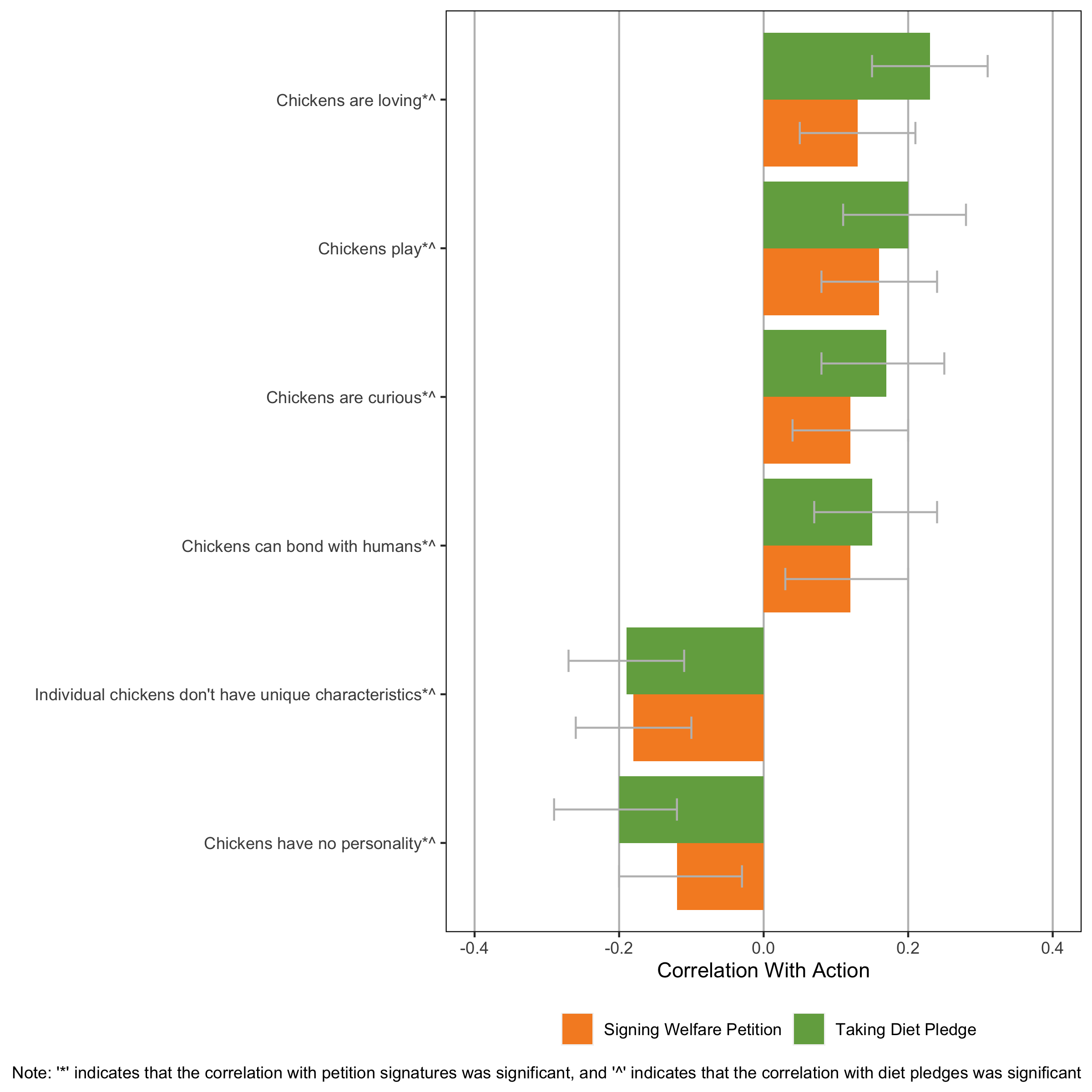

Chicken Personality Beliefs

Chicken personality beliefs had the largest average association with taking the diet pledge (r = .19, SD = .03) and the third-largest association with signing the petition (r = .14, SD = .03). People who agreed that chickens were loving were more likely to take the diet pledge, and the item was one of the strongest individual beliefs in the survey. The belief that chickens don’t have unique personalities had a particularly strong negative association with petition-signing—that is, people who agreed with it were less likely to sign.

Figure 10: Chicken Personality Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

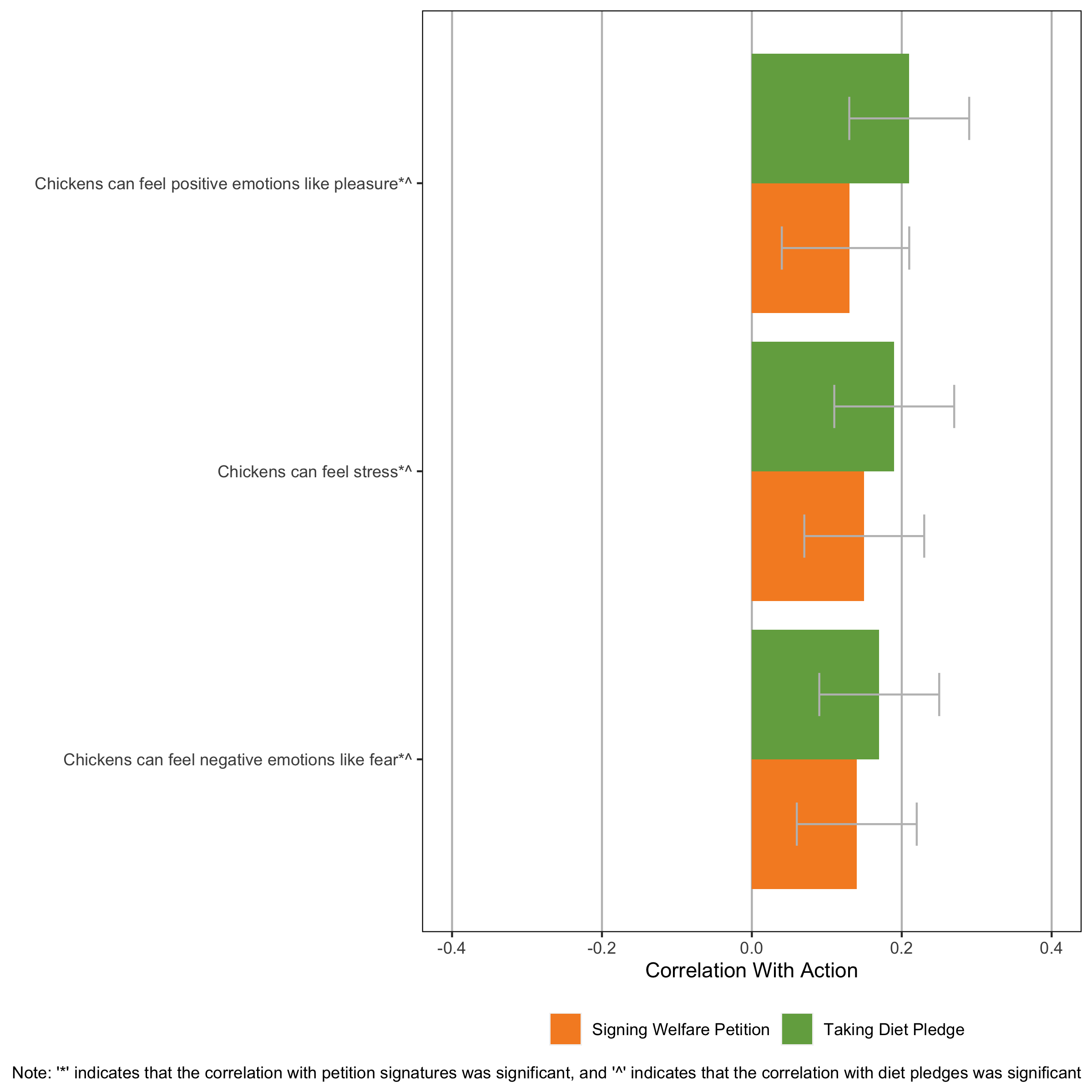

Chicken Emotion Beliefs

Beliefs around the emotions of chickens were tied for the top spot with personality in terms of the average correlation with taking the diet pledge (r = .19, SD = .02), and were second in terms of their association with the petition signatures (r = .14, SD = .01). Similar to the fish emotions category, this was largely due to the consistency of the items in this belief category, as no single item performed particularly strongly. However, because the category as a whole performed well and consistently, it should likely be given consideration in advocacy efforts.

Figure 11: Chicken Emotion Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

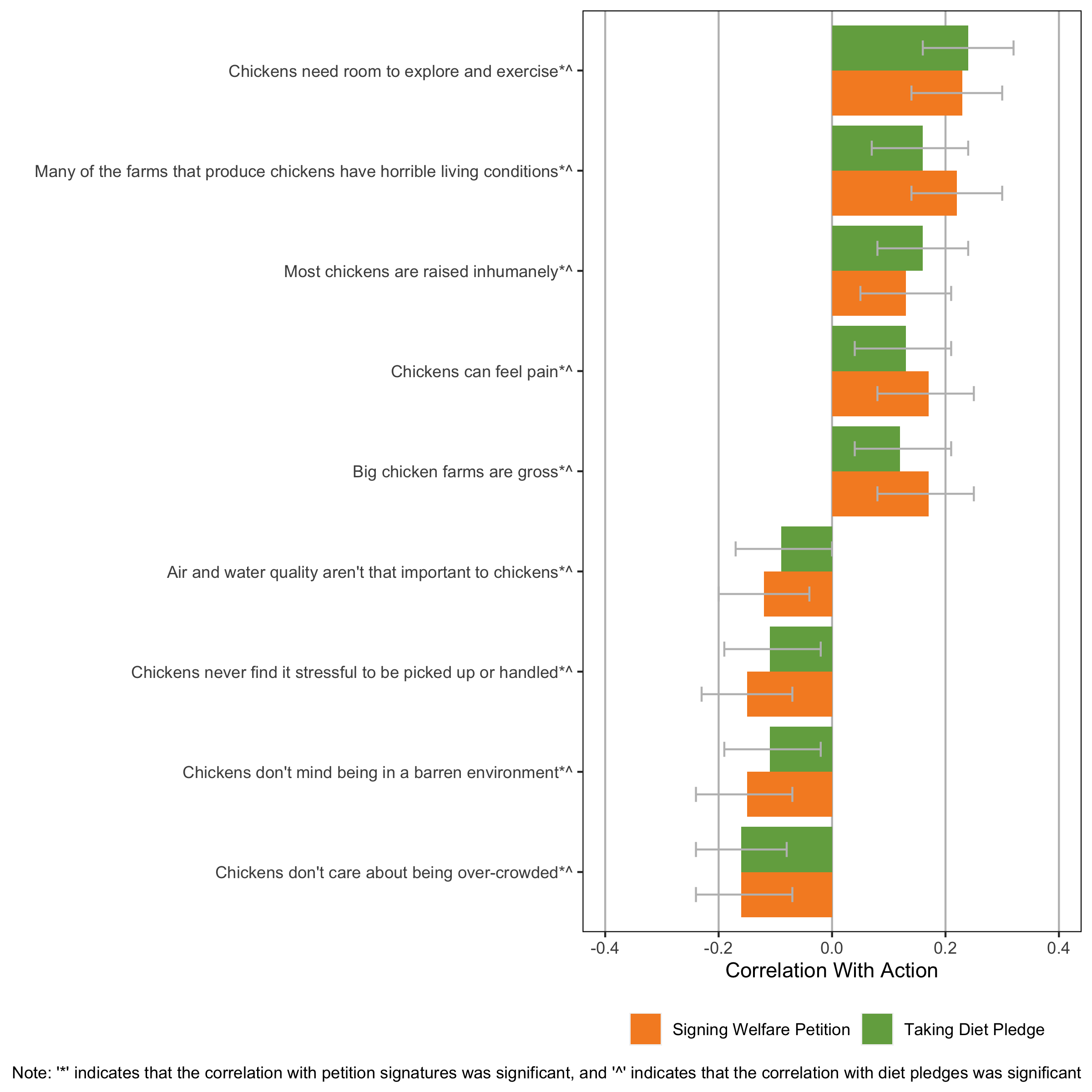

Chicken Suffering Beliefs

While average chicken suffering beliefs were only the fifth-strongest category for diet pledges (r = .14, SD = .05), they were first for petition signatures (r = .17, SD = .04). This was on the strength of two items in particular, which had the strongest correlations across all items for chicken petition signatures: the belief that chickens need room to explore and exercise and that many chicken farms have horrible conditions.

These items are clearly important for petitions and should be considered by advocates using this approach. The belief that chickens need room to explore and exercise was also very strong among individual beliefs for dietary pledges. Based on these results, we feel that education on suffering is very likely to be important, particularly for petition signatures.

Figure 12: Chicken Suffering Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

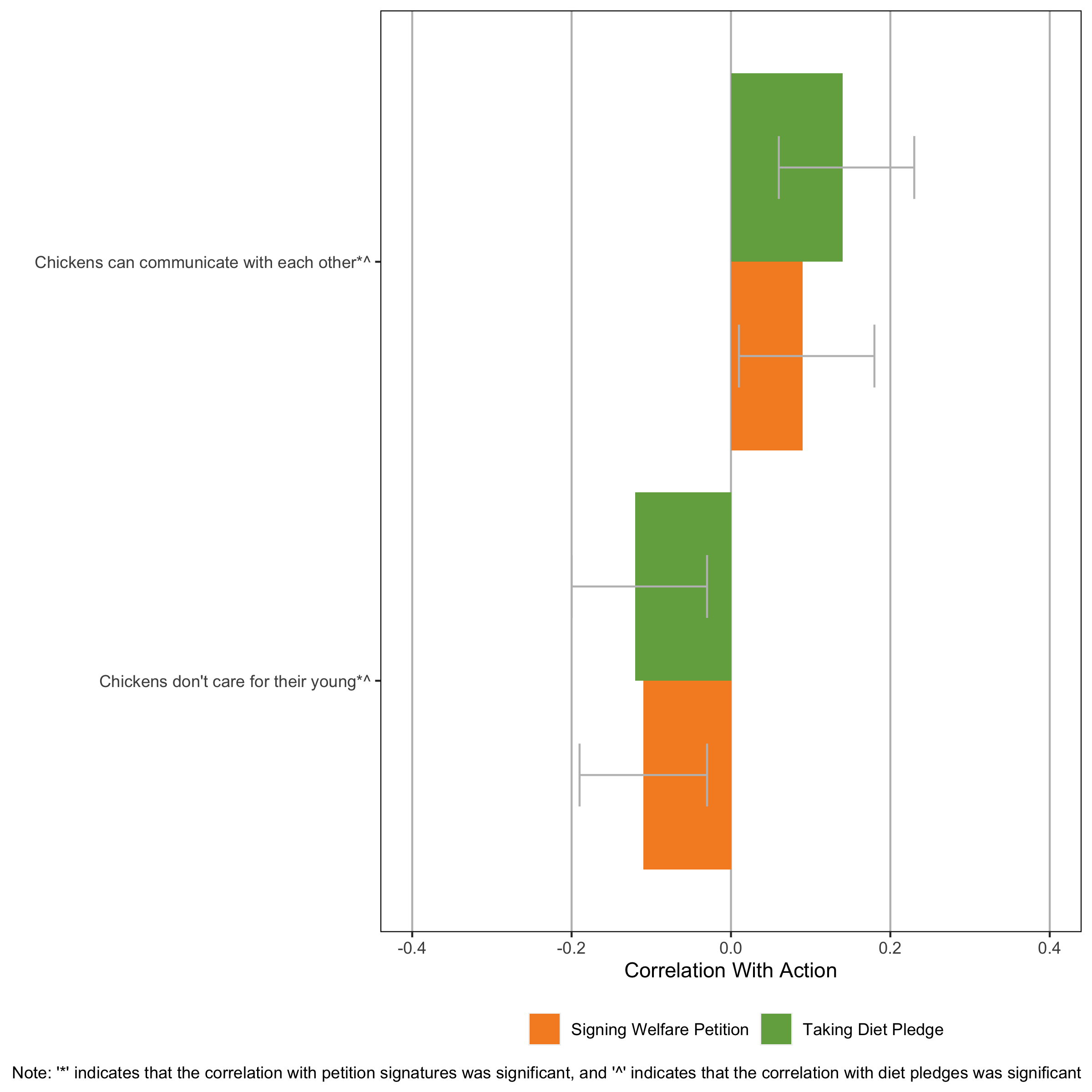

Chicken Social Beliefs

Beliefs about the social nature of chickens had the sixth-largest average association with diet pledges (r = .13, SD = .01) and the fifth-largest association with petition signatures (r = .10, SD = .01). Neither of the individual items particularly stood out.

Figure 13: Chicken Social Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

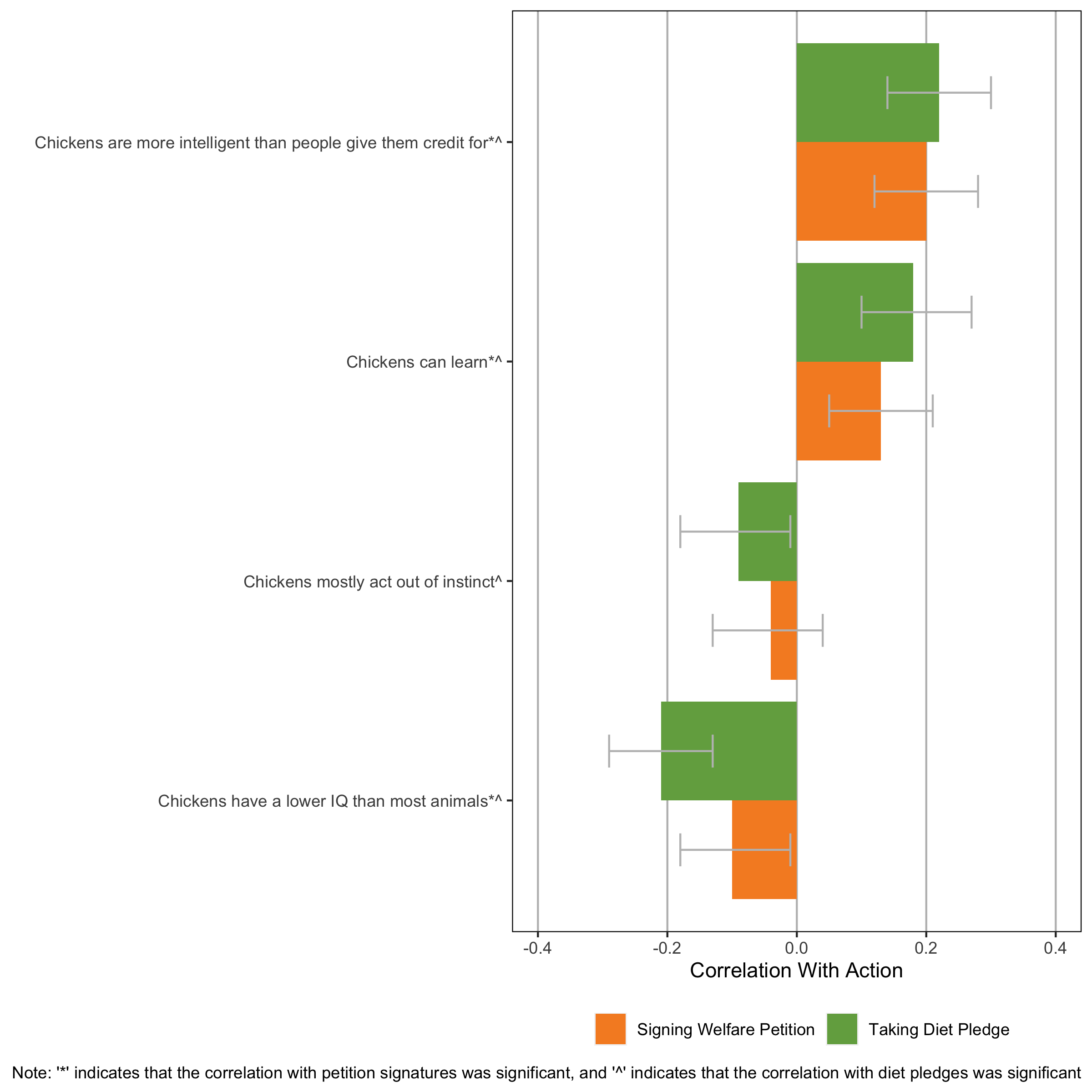

Chicken Intelligence Beliefs

Beliefs around chicken intelligence were third in terms of average correlation with diet pledges (r = .18, SD = .06) and fourth in terms of petition signatures (r = .12, SD = .07). For diet pledges, two individual items stood out: beliefs about chickens being more intelligent than people give them credit for (which tended to be higher among those who signed the diet pledge) and the belief that chickens are less intelligent than other animals (which tended to be lower among those who signed the pledge). The belief that chickens deserve more credit for their intelligence was notably more prevalent among those who signed the petition.

Figure 14: Chicken Intelligence Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

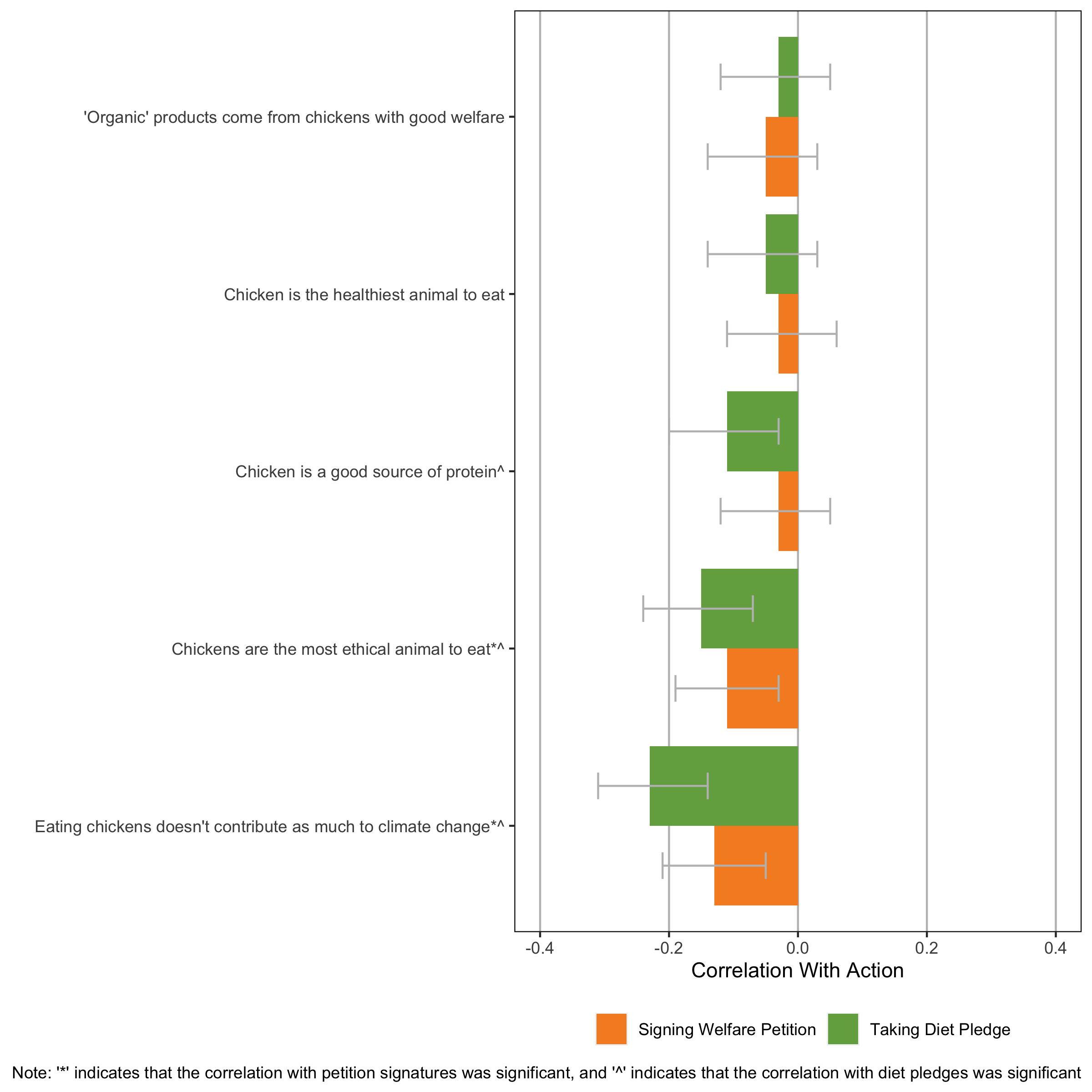

Chicken Consumption Beliefs

Beliefs relating to chickens as food had the weakest average performance for both diet pledges (r = .11, SD = .08) and petition signatures (r = .07, SD = .05). However, one belief was notable: those who agreed that chicken didn’t contribute as much to climate change as eating other animals were less likely to take the diet pledge. This belief had one of the largest associations with the diet pledge of all the individual beliefs.

Figure 15: Chicken Consumption Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

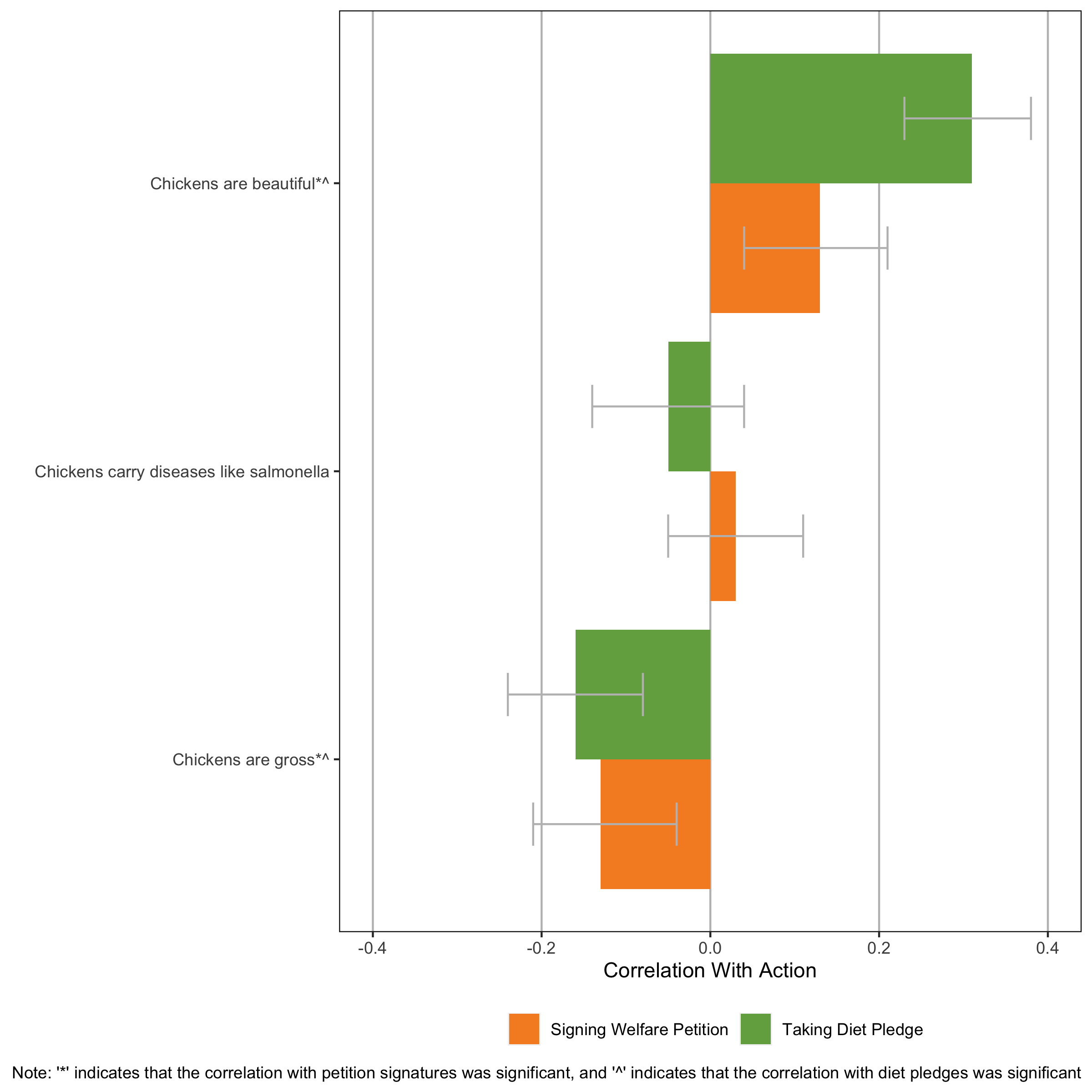

Other Chicken Beliefs

Due mainly to the strength of one item—the belief that chickens are beautiful—the “other” category of beliefs was fourth in terms of average association with pledges (r = .17, SD = .13). In fact, this item had the largest correlation with diet pledges of any of the individual beliefs for chickens, and those who agreed were more likely to take the diet pledge to reduce their consumption. The category was less strongly associated with petition signatures, coming in sixth overall for petitions (r = .10, SD = .06).

Figure 16: Other Chicken Beliefs And Animal-Positive Behaviors

Interpretation & Future Directions

This study was an important first step in understanding the beliefs people have about chickens and fish, and how they relate to pro-animal behaviors. But while the above analyses provide important clues, more research is needed to demonstrate whether these beliefs are useful in actually shifting animal-positive behaviors, or whether they are simply associated with diet pledges and petition signatures. In other words, can the beliefs be shifted to bring about behavior change, or are they only correlated with behavior because people who care about animals already hold those beliefs?

We plan to follow this study up by replicating it in additional countries. This will give us a sense of the beliefs that are held in other cultural contexts. We will also be designing an intervention that will attempt to use some of the beliefs that appear most important based on this research to try and increase animal-positive behaviors. This will likely take the form of an experiment (randomized controlled trial), where different groups of people are shown an intervention based around different beliefs to see if any of them influence animal-positive behaviors.

Thank you for reading, and please let us know if you have any questions.