Summary

- Globally, one third of women and girls experience violence during their lifetime

- Violence against women and girls (VAWG) has significant health, economic and social effects for survivors, perpetrators and society more broadly.

- There is moderate and growing evidence that interventions that seek to prevent VAWG from occurring are cost-effective

- VAWG as a cause area has moderate absorbency for more funding, with a number of potentially promising avenues for funding

- There are several key uncertainties that were identified in this report, concerning the scalability of interventions in this area, how interventions would be received by communities and governments, and the comparative and additional benefit of directly addressing VAWG versus its risk factors.

- Overall, this report recommends that VAWG be considered as a new cause area.

Disclaimer: This report represents a shallow dive into this cause area; approximately 20 hours was spent on this report. With more time, several of the key uncertainties presented through the article might be addressed, and more time would be spent analysing potential opportunities for new organisations and funders in this space. However, I would anticipate that this is unlikely to significantly change how promising VAWG is as a cause area

How big a problem is violence against women and girls?

Nearly one third of women and girls aged 15 years of age or older have experienced either physical or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) or non-partner sexual violence globally, with 13% (10–16%) experiencing it in 2018 alone (Sardinha et al 2022). This figure does not include a number of areas, including sexual harassment, female genital mutilation, trafficking in women or cyber-harassment (UN Women). It is also likely that this figure, due to chronic under-reporting, underestimates the true burden of VAWG,

The Global Burden of Disease, which includes information on IPV but not VAWG more generally, reports it as the 19th leading burden of disease globally- it is responsible for 8.5 million DALYs and 68 500 deaths annually. In several countries, violence against women is in top 3-5 leading causes of death for young women aged between 15 and 29 (Mendoza et al 2018). In addition to the direct harms of VAWG, it is a significant risk factor for other conditions- VAWG is responsible for 11% of the DALY burden of depressive disorders and 14% of the DALY burden of HIV in women (Healthdata.org).

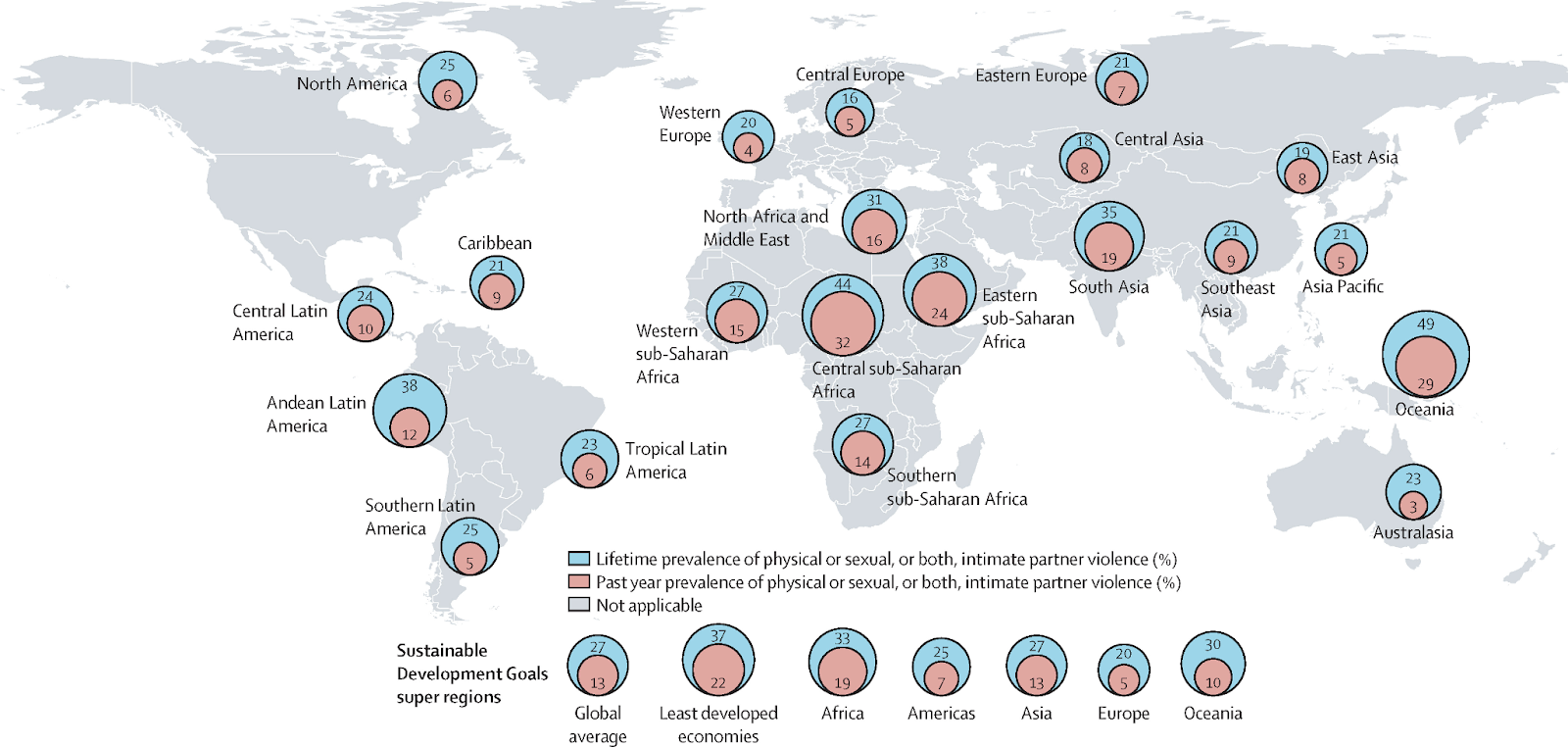

Globally, the rates of VAWG are both alarmingly high and have slightly increased over the last 30 years, despite gains in other areas of women’s health, such as maternal care (Think Global Health). Further, there are certain countries and regions of the world (e.g. several Asian countries) that have seen significant increases in the rates of VAWG over the last two decides (Borumandnia et al 2020). The geographical distribution is shown in the figure below, which takes data from the 2018 WHO Global Database and which was published in The Lancet earlier in 2022 (Sardinha et al 2022)

What effects do violence against women and girls have?

Health costs of violence against women

The health consequences of VAWG are significant; they can be immediate and acute, long-lasting and chronic, and/or fatal. Some of the most common health consequences of VAWG are summarised in the table below.

| Physical | Sexual and reproductive |

-Acute or immediate physical injuries, including bruises, lacerations, burns, bites, and fractures - more serious injuries leading to long term disability, including injuries to head, eyes, ears, chest and abdomen -Gastrointestinal conditions - chronic pain conditions -death, including femicide | -unintended/unwanted pregnancy -unsafe abortion -sexually transmitted infections, including HIV -chronic pelvic infection -fistula |

| Mental | Behavioural |

-depression -sleeping and eating disorders -stress and anxiety disorders e.g. PTSD -self harm and suicide | -harmful alcohol and substance abuse -having abusive partners later in life -lower rates of contraceptive and condom use |

Collating the evidence for the odds ratio (OR) of VAWG for each of these conditions would be valuable but was not prioritised for this shallow report. Instead, here are a select number of statistics related to the health consequences of VAWG:

- Multiple injuries (e.g., broken bones, facial injuries, eye injuries, head injuries, broken or dislocated jaw) were nearly 3 times more likely to be reported in those who experienced past year IPV compared with women who were never abused (OR 2.75; 95% CI:1.98–3.81) (Anderson et al 2015)

- IPV was correlated with an approximately 1.6 OR of suicidal ideation , and a 2.0 OR of depressive symptoms (Devries et al 2013)

- Survivors of VAWG are significantly more likely than other women to report overall poor health, chronic pain, memory loss, and problems walking and carrying out daily activities (WHO 2005)

Economic costs of violence against women

In 2016, the global cost of violence against women was estimated by the UN to be US$1.5 trillion, equivalent to approximately 2% of the global GDP (UN Women 2016). The economic cost seems to have two major contributing factors:

- Lost economic productivity due to absenteeism and lost productivity: A study in Ghana (Merino et al 2019) found that for women experiencing any form of violence, the total days of lost productivity was 26 days per woman in the past 12 months. This translated into nearly 65 million days at the national level or equivalent to 216,000 employed women not working, assuming women worked 300 days in the year. Overall, the economy was estimated to lose output equivalent to 5% of its female workforce not working annually due to VAWG. Similar results have been shown in India and Uganda (Puri 2016)

- Increased utilisation of public services: Survivors of VAWG have increased utilisation of public services, including health services, criminal and civil justice systems, housing aid and child protection costs, as well as specialist services. The European Institute for Gender Equality estimates that this incurs a similar (if not greater) economic cost than lost productivity.

Social costs of violence against women

There are very strong and reasonably self-evident arguments for the social harms of violence against women. The UN Sustainable Development Goal 5, which focuses on gender equality, includes the elimination of all violence against women and girls (VAWG) by 2030. Due to time constraints, I have not offered a more in-depth analysis of the social costs of violence against women; in lieu of this, I recommend the following resources:

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation: A conceptual model of women and girls’ empowerment

- VAWG and Human rights

Even though justice and equity arguments are more difficult to conceptualise and estimate the benefit of (Kapiriri and Razavi 2022), these are strong virtues which a majority of the population value, and which work in this space is likely to be in service of.

What works in reducing the prevalence and harms of violence against women and girls?

In conceptualising what approaches might be tractable in preventing VAWG, the universal public health model of primary, secondary and tertiary interventions was utilised.

| Intervention type | What it is | Examples | Cost-effectiveness |

| Primary prevention | Preventing violence before it happens | -Community based education program around gender norms -Counselling and couple support | Likely to be cost-effective: Moderate to strong evidence |

| Secondary prevention | Early detection and intervention | -Screening and referral systems in primary care | Unlikely to be cost-effective |

| Tertiary prevention | Treatment of violence that has already occurred | -Support services for survivors of IPV | Unlikely to be cost-effective |

Primary prevention

Several primary prevention programs have shown promising cost-effectiveness profiles. These programs have mostly focused on community activism to change gender norms and attitudes, school and couple-based interventions to focus on transforming gender relationships (What Works). There are three RCTs focused on primary prevention that could be identified through a literature search:

- Community based action teams (RCT in Ghana) - An RCT of a Rural Response System, which uses community based action teams to increase knowledge about VAWG, change individual and community attitudes towards gender equality and violence, positively change gender and societal norms and behaviours, as well as counselling & couple support and better referral systems found a cost per DALY averted of US$52 among female participants.

- Unite for a Better Life (RCT in Ethiopia)- An RCT of over 6600 households in rural southern Ethiopia, which had a combined workshop-based and community mobilisation approach (delivered to men, women and couples in the context of a traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony), reported a cost per year free from physical and or sexual intimate partner violence of US$194 at the community level and US$2726 for workshop participants. This equates to a cost of US$78.4/DALY,

- SASA! Community mobilisation intervention (RCT in Uganda)- In Uganda, an RCT of the effectiveness of a community based intervention engaged activists, ssengas (traditional marriage counsellors), drama groups and community based organisations, training them to plan and run various activities including community dramas, poster discussions, small group activities and one-on one ‘quick’ chats. This intervention found a cost per year free from IPV of US$460, which equates to a cost of US$184/DALY

Overall comments:

- These studies suggest that targeted primary prevention interventions may be cost-effective when purely considering the health effects

- If the economic and social effects, as well as indirect effects on other health domains were modelled, such interventions are likely to look more promising (my subjective estimate is by a factor of 2-5).

- A number of these studies have been published within the last 12-36 months; I am unaware of any other cause area reports into VAWG, but these studies are likely to update towards this cause being more promising.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention interventions for VAWG have predominantly focused on screening and early identification of women who are at risk of or who have recently been victims of violence.

- A meta-analysis of screening and referral programs for women who currently or in the past suffered from violence (O’Doherty et al 2014) found that programs found a total of 11 trial; based on these, screening programs increased the identification of IPV (risk ratio 2.33, 95% CI 1.39-3.89), but there was no evidence that screening increased referrals to domestic violence support units and no evidence of reduction in IPV after 3-18 months.

- In their search, the authors identified one study (Feder et al 2011) that conducted an economic evaluation- unlikely to be cost-effective.

- Since then, a few studies have conducted economic evaluations of secondary prevention programs (Devine et al 2012); they found these programs to potentially be cost-effective at a cut-off of £20 000/DALY, and very unlikely to be cost-effective at £1 000/DALY.

- There are several ongoing trials looking at effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of secondary prevention e.g. the HARMONY trial, a multi-centre RCT in Australia

Overall comments:

- Although these studies are undertaken predominantly in a HIC setting with higher implementation costs and slightly lower burden of VAWG, it sees that secondary prevention may be effective, but is is unlikely to cost-effective

Tertiary prevention

Tertiary prevention has predominantly focused on the provision of health and other services (e.g. legal, accommodation) to reduce the burden of VAWG that has already occurred. In researching this space, a few key pictures emerged:

- Tertiary services, although undoubtedly important, are in general expensive to run. There may be some exceptions to this e.g. certain types of short-stay housing services.

- There is a lack of explicit cost-effectiveness analysis of such programs, as they are often integrated or sub-programs of existing public services

- Tertiary prevention, certainly within HIC and likely in LMIC as well, receives a significant amount of funding in this space. .

Who is working on this?

There are a number of countries and some international organisations that are funding work to decrease VAWG:

- There seems to be a focus, especially in HIC, on tertiary prevention, with provision of health and other services (e.g. accommodation) for survivors of VAWG receiving a significant proportion. Examples of this include UK data on government funding to tackle VAWG over the last decade shows a fairly constant funding of approximately £40 million pounds/year, focused on tertiary services.

- The major global fund is the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women. It works with civil society organisations to prevent violence, improve access to service and strengthen implementation of laws and policies. Since 1006, it has awarded US$198 million to organisations and partners in this area.

- There are a number of local funders that have their own individual focus (a select list can be found on Charity Excellence Framework). Most of these organisations and funds are small, with individual contracts and grants ranging from US$100-100 000. They do not seem to have capacity to offer medium to large scale grants, such as those required for scaling up or running RCTs.

Overall, for the scale of the issue, it seems like VAWG receives insufficient attention and funding (you can look here for visualisations of where global health funding goes). For instance, even looking specifically within women’s health (which in and of itself is neglected), VAWG is neglected; for instance, the Gates Foundation alone has committed 3.1B dollars towards family planning services within the next 5 years.

What could be achieved with additional investment?

Although there are some funders and organisations working in the space, it seems that there are several gaps in the current landscape, and that this area has moderate absorbency for funders:

Scaling up prevention programs

A funder could help to scale up prevention programs that have shown early and promising signs of cost-effectiveness from initial RCTs. Based on the above evidence, this is most likely to be community-based primary prevention programs that seek to change gender norms and attitudes. The UK government, in partnership with Raising Voices, Social Development Direct and Care International, started ‘What Works: Impact at Scale’, a 7 year and £46 million pound project that hopes to scale up prevention programs in LMIC that have shown initial promising cost-effectiveness. Despite this, it is likely that: 1. There are likely to be other geographies or programs that are not under the remit of this program, 2. This organisation could be strengthened with additional funding.

More RCTs

Although we have some initial proof of concept for several interventions in this space, it is likely that additional studies to see what works, most likely in primary prevention and secondary prevention of VAWG in sub-Saharan Africa or Asia, would be quite helpful. Indeed, as noted in several reports in this space, a critical challenge is to develop a robust evidence base for impactful prevention that can be rapidly scaled up and sustained within the fiscal limits of LMIC governments and their development partners. The kinds of studies that I would be interested to see here are those that have worked in other global health and development fields, such as mass media campaigns (e.g. radio campaigns) and digitally-delivered interventions. Since RCTs are reasonably expensive to run, the support of a major funder might be pivotal in building a robust evidence base.

Policy advocacy

It seems likely that policy advocacy to encourage governments to institute national action plans for VAWG, and have national action plans that have a strong inclusion of primary prevention interventions, would be impactful. There are also potentially some direct policy and legislative changes that may have significant impact e.g. the right to divorce without the consent of a husband (Ardabily et al 2011). Although the cost-effectiveness of policy advocacy has not been explicitly modelled in this report, I likely think that encouraging governments to develop robust plans to tackle VAWG is likely to be a cost-effective strategy that is reasonably tractable and a good investment for a funder. However, there is low confidence for this claim, and further specific research into this would be beneficial.

Key uncertainties

How scalable interventions that aim to reduce VAWG are

It is unclear how context dependent the factors that contribute to VAWG are, and to what extent interventions that work in one context are generalisable. A number of the primary prevention strategies have focused on changing gender-norms in Sub-Saharan Africa; it is unclear to what extent this mechanism would work in other contexts (Bates and Glennerster 2017). In addition, the specific policies and legislative context and environment between countries are likely to be different, and it is unclear how transferable policy asks in one context might be in another.

The complex sociocultural nature and factors that contribute to VAWG may lean towards this issue having different mechanisms in different contexts and therefore being less scalable.

Although this question was not rigorously addressed due to a lack of time, my initial subjective thoughts on this are:

- There are likely to be some interventions, particularly wide reaching primary prevention techniques (e.g. mass media campaigns), that are reasonably transferable between contexts

- This is something that can only be figured out by scaling up, which itself justifies this being a cause area that attracts an influx of funding.

How interventions would be received by communities and governments

Interventions that seek to talk about gender norms or increase access to care for women who are survivors of violence may not always be received positively. There are likely certain contexts within which such programs may not be as effective and perhaps spark outrage and backlash. In light of this, it would be important to :

- Understand the indirect and flow-on effects of interventions for VAWG; in particular, it would be important to consider and attempt to answer questions like: is there a reactionary increase in VAWG in response to these programs? Is there a reduction in the prevalence of VAWG but an increase in its severity? A thorough consideration of these negative externalities would be necessary to ensure that any intervention is positive and effective.

- Ensure that interventions are developed in close partnership with local communities (Seward et al 2021). It seems that this might mitigate at least part of this concern and is likely to inherently be a better approach (Horton 2021).

The relative benefit of addressing risk factors

There is some literature that looks at the effects of reducing the burden of VAWG through modifying some of the underlying risk factors and drivers. For example, given that poverty and economic hardship are risk factors for VAWG, providing cash transfers to women, there are some studies that have looked at the effects of cash transfers on rates of VAWG. Another example of this might be programs that seek to reduce alcohol consumption, which is another key risk factor for VAWG.

The effect of modifying these risk factors on VAWG is inconclusive, and the effect sizes tend to be relatively small. It is likely that even though reductions in VAWG may be a positive externality of other programs, they are unlikely to be cost-effective in preventing VAWG (What Works). Especially given the increasing burden of VAWG, it is likely that direct interventions are likely to be crucial .

Conclusion

Overall, VAWG represents an important cause area. Beyond the deaths it causes, the majority of its burden comes from its other health impacts and its immense economic cost. Over the last decade, there has been significant improvement in the evidence base for interventions preventing VAWG, which may be cost-effective and scalable. Although there are several organisations and funders in this space, including public funders, there seems to be reasonable scope for more work and funding in this area. Based on this shallow report, this report recommends violence against women and girls as a cause area.

**

Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge the following individuals, who provided feedback on an earlier draft of this report: Ilona Arih, Toby Webster, Abe Tolley

Personal motivation: I was initially motivated to investigate VAWG in part due to my personal and professional interest in the area; as a healthcare worker, I have seen the devastating effects of VAWG in both the hospital and primary care setting. Despite this initial interest motivating an exploration of this cause area, I believe that the report is nonetheless unbiased and balanced.

Good post, well done! Cost effectiveness analysis was done well. There are a couple things I'd like to see in the cost effectiveness that could further enhance the argument. First, I don't have a good handle on the cost per DALY through well-known givewell interventions like AMF or the equivalent for direct giving, and it would be good to see that compared (comparison with other health variables might be helpful).

Second, if the sources are strictly measuring medical and health outcomes of reduced violence, the true magnitude of the benefit could actually be quite a bit more, because plausibly there are additional well-being benefits not captured by a pure medical analysis.

You have mentioned economic benefits in other parts of the report so I suppose it would be helpful to capture that in the analysis of specific cause areas too.

That said, cost per DALY of $52-78 sounds reasonably good at least?

That's true for lots of other interventions too. Has it been measured how much happier it makes parents when their children don't get malaria?

Maybe we should get better at measuring these things :)

Hey Guy completely agree with you; I think that the 'Worldview Investigations' sub-section of this prize might be looking for this; from my perspective, something like this would be quite valuable.

It is much more worth the time to measure direct impact - how many people were prevented from falling ill. And indirect impacts - families who didn't fall into poverty or economic hardship due to paying for treatment/lose of work earnings. Contributions in these areas imply an increase to well-being.

There are many areas that would be worth measuring well-being increases more explicitly though. Violence against women and girls is definitely one of them.

Hi Ben- thanks! I didn't have the time to do a robust cost-effectiveness analysis of this intervention, and with low certainty, I didn't feel comfortable making direct comparisons to AMF/other direct interventions. However, I think that an estimate roughly $50-80/DALY for purely health effects seems reasonable.

As mentioned in the text, I imagine the benefit-cost profile is multiplied by a factor of 2-5 if economic benefits are considered

Thanks for the write up Akhil, one aspect of this cause area you may also like to be aware of is fear/feelings of safety in women. Beyond direct victimisation, fear of violence (which doesn't require someone to be a victim although it is a primary factor influencing the duration and intensity of fear) also adds to the case for this being a cause area.

Correspondingly, there is a widespread impact. Fear will influence someone's pattern of life which will have various health, economic, and social costs. Interventions which also reduce fear in women could therefore also be worth exploring.

I understand you probably haven't had much chance to delve into interventions and root causes as you are focusing on building this as a worth-while cause area for investment but I would be interested to understand more on what are the cause/sources of violence (is it street crime, violence by male partners, etc.) .

Hey Darren, great point! Fear of violence and the broader affects of that was not something that I had considered, but seems like it is a significant issue that is worth investigation.

In terms of the context within which violence happens (or its source), from my understanding, most of it is within the domestic environment, with the vast majority being by someone who is known to the victim.

Broadly, I think that root cause analysis would be a really interesting step in 'unlocking' new and potentially promising investigations in this space. WIth more time, I would love to do this

If you have any more resources on the same, please send them across

Related: workforce participation by women in India is very low (~20%) and has been dropping, partly because women and their families are worried about harassment or violence at work or while commuting. The actual rates of workplace or commuting violence may not be happening as often as violence in the home, but it may cause bigger changes in behavior.

J-PAL just sent in their newsletter this study report from April, that seems to address this exactly, judging by its abstract:

Hey Julia really great point. And that World Bank resource that you point to is an excellent read. Thank you :)

I would like to add to Darren Tindall's point. The initial post (which was fine in itself) was narrowly focused on individual women who have been victims of violent acts. But widespread violence against women has a cascading and corrosive effect on all women's wellbeing. There is effectively a "tax" on women, for being women. At night, women and girls will often pay for a taxi or uber, because they are not safe walking or taking public transport. Women everywhere often avoid parks or isolated areas, for fear of being attacked. The constant vigilance required takes a mental toll, as well as restricting their activities. In addition, this is violence aimed at them specifically BECAUSE they are women (a fact they can do nothing about). Continued fearfulness, at home and in public places, has a cost, although it is difficult to assess that in dollar terms. It is not dissimilar to the cost of racism.

Hi Deborah, I completely agree. I think that in particular, the economic and social costs of VAWG extend beyond the victim, and likely have quite significant broader and society level effects.

I think you are right that it is difficult to assess in dollar terms- I have not been able to find anything that explores this in a robust or quantitative way, but I think some of the links that Julia and others pointed to are good starts.

Thank you for your comment and taking the time to read this.

Hey All, Akhil there is a good report which delves into the some of the topics highlighted here but it is focused on London. It also discusses how this specific sub-set of women's safety relates to the domestic setting: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/urban-lab/sites/urban-lab/files/scoping_study-_londons_participation_in_un_womens_safer_cities_and_safe_public_spaces_programme.pdf

Caveat: one peeve I have with this report is that it omits the fact there is also high levels of urban fear in men also (for example on public transport this is 10% lower than women which seems to suggest high levels of fear in both sexes and therefore a bigger problem at play). None the less, extreme vast majority of sexual harassment/assaults on public transit occur against women.

I haven't read the report but I just want to point out that there is some possibly related research by an EA organization Founders Pledge on women's empowerment. In particular, they review a charity No Means No Worldwide which teach courses to kids to prevent sexual assault. I apologize if this is not very relevant.

Thank you for the comment Saulius- I think interventions for women's empowerment may have some overlap with those for VAWG. The example that you point to, No Means No Worldwide, is a great example- strongly inter-related.

In Israel we have a lobbying group (of one person) who passes laws like "if you're a hospital treating a rape victim, keep the evidence, don't throw it away".

I donate there, and their huge amount of leverage (salary for one person for 1 year = a few nation wide laws changed, which will effect lots of people for lots of time) make me think this might be an EA-level effective cause even though it's a first world country.

Website (Hebrew, but maybe chrome can translate).

Does she work alone because she doesn't have enough funding? Or does she just think she's effective enough as it is? I assume it's the first one, but after lighting a torch in the official Independence Day ceremony, you'd assume she'd get some publicity...

I have no idea

The reality tends to be unsatisfying, like "I hate managing other people" or "I don't know how to hire" or so - that's my prior.

Perhaps if EA would offer to just hand her another $100k she'd find what to do with it, or at least want to talk to some consultant if she indeed has that kind of problem? I don't know. Don't want to bother her if I don't have anything serious to offer

I think her impact is way above how much money she is getting and perhaps if anybody does retroactive public good's funding - we could give her something (?)

Happy to help arrange this down the line.

P.S

I don't believe the problem effects only one third of women and would I'd be happy to take bets on what we'll discover in the future when we have better studies (as judged by you).

Hi Yonatan,

That is really interesting; I think policy advocacy to change laws that prevent or reduce VAWG is a promising avenue, so thank you for sharing your experience from Israel.

On your second point, yeah I would probably agree that it likely affects more women and girls; completely my intuition and from my personal experience as a doctor, but I would also be unsurprised if it was higher. More research would help with this!

How does this compare to violence against men and boys as a cause area? Worldwide, 78.7% of homicide victims are men. Female genital mutilation is also generally recognized as being a human rights violation, while forced circumcision of boys is still extremely prevalent worldwide. For various social reasons, violence against males seems to be a more neglected cause area compared to violence against females.

Hey everyone, the moderators want to point out that this topic is heated for several reasons:

We want to ask everyone to be especially careful when discussing topics this sensitive.

Just a quick question: You write that the cost for 1 year free from IPV is about US$194, and that this means the intervention costs US$78.4/DALY

If I understand this correctly, it would mean that 1 year free from IPV is about 2.5 DALYs? Is that correct? It seems to imply that experiencing IPV is worse than death... which might well be true, but the more likely explanation is that I misunderstand the DALY conversion. Could you clarify?

Great question :) So this model used accounts for multiple different types of alleviated health burden from each year free from IPV. Specifically, each year free from IPV prevents chronic conditions that cause disability that lasts many years, femicide, as well as acute issues within that year itself. That would explain why 1 year free from IPV can be more than 1, and in this case roughly converts to 2.5 DALYs.

Thank you for the explanation! I sincerely appreciate, since I realized that my question could be perceived as trolling or nitpicking on the cost-effectiveness estimates. My intention is rather to understand better the impact of these interventions. Also, these DALY calculations are just hard (at least for me).

I think the answer makes sense.

Do you have a reference to the model that you've used (pardon if I missed the link)? I would be interested to look at it in a bit more detail. For example, my gut feeling is that a single or a few instances of IPV might already cause chronic damages; and so to avoid this damage we would be interested more in IPV-free lives than IPV-free years.

EDITED to add: On the other hand, it would seem likely that the effect of an intervention lasts for longer than a year, and thus that the beneficiaries would benefit from a reduced IPV risk for much of their lives.

A clarification, after having read more about the interventions:

The studies asked women whether they experienced various forms of intimate partner violence over the last year. If a woman reported any form of violence, that was coded as a "case of IPV". Multiple or repeated experiences within the last year do not change the coding, it is still just one "case of IPV". The "Unite for a better life" intervention averts one case per US$194.

This means one woman more who did not experience violence in the last year. Which probably also means that she is in a lower-risk relationship, and that this state will persist for some time in the future.

https://www.epw.in/engage/article/gender-norms-domestic-violence-and-southern-indian

Study providing evidence in favour of the idea that development may be insufficient to reduce support for wifebeating (and therefore targeted interventions may be needed). However, this study doesn’t show how support for wifebeating is associated with IPV.

Would this be specifically violence against women and girls in poor countries, or globally?

With the caveat that I did not do a geographical assessment in this shallow, I would guess that it would be likely that this would be initially targeted in certain LMIC countries (especially in Africa and Asia) as they have a high and increasing burden of VAWG and have been the focus of prior studies in this space. However, it is also true that the burden of VAWG is considerable and not significantly dissimilar between LMIC and HIC, so I have low confidence on this claim.

In addition to the difference in VAWG burden, there are also differences in implementation costs. Interventions will be cheaper in low-income countries than in high-income countries.

Not necessarily. It will depend heavily on the type of intervention and the issue . If the issue is rooted in entrenched cultural attitudes due to low education, conservative attitudes, and entrenched traditional values as I suspect would be the case in many low-income countries then an intervention may be prohibitively more expensive to implement in a low-income country.

Lobbying governments may also be easier in higher income countries in terms of their ability to enforce new norms.

I love this, thank you so much for writing this up. I'm actually kind of mad at myself for not writing about this, but so glad that you did it so well! I've been thinking about VAWG and how EA doesn't give enough attention to this, and often have been shunned or politely asked to focus on bigger problems by many EA's, and didn't yet have the courage to actually sit down and write everything I feel about this, and all the research I could have done to articulate my point. I'd be very happy to be a big part of this initiative of exploring this cause-area within EA, if there is something you have thought of already.

Hi Akhil, I really like this report: thank you for writing it up here!

Something that I think could additionally add to the impact of VAWG (although clearly difficult to estimate/ maybe not worth it for a shallow dive) is the somewhat cascading/ generational nature of domestic violence and associated trauma– e.g. that if you experience more Adverse Childhood Experiences, your children are also more at risk for ACEs, etc.

It also has struck me before that social norms about VAWG/ intimate partner violence vary strongly across regions. I think social norms are very powerful; do you know of any charities aiming to shift social norms regarding VAWG/ intimate partner violence? (E.g. I'm thinking along the lines of narrative stories over the radio, but there may be other alternatives in this area).