Summary

- Obesity is a major risk factor contributing to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes and cancer; NCDs are the number 1 cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide

- High BMI, which includes being overweight or obese, is associated with 5.02 million deaths a year and 160 million DALYs; obesity itself is responsible for approximately 60% of this.

- Although curbing obesity is probably not that neglected, there is a lack of rigorous, evidence-based organisations in the space

- Given that the rate of obesity is rising and there seems to be no significant change in direction, I expect investment in obesity reduction to have a high counterfactual value

- There are several potentially cost-effective interventions in this space, most of which focus on prevention of obesity through policy approaches. They are potentially very cost-effectiveness, with some interventions being under $50/DALY and potentially as low as $2-7/DALY

- I expect that tractability may be a difficulty in this space, although this is the area of the report that I have the least confidence on and spent the least amount of time on.

- Overall, this report is cautiously optimistic about obesity as a cause area, suggesting that it may be suitable as a new program at Open Philanthropy, or as a share of a larger portfolio on non-communicable disease prevention.

Disclaimer: This report represents a very shallow dive into this cause area; approximately 7-8 hours was spent on this report. With more time, I would address some of the key uncertainties in this report and areas where I spent less time, which I imagine could update me moderately. I would invite anyone who has expertise or knowledge about the area to please comment or send me a message!

Why obesity?

- Non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases ( e.g. hypertension, strokes, heart attacks), respiratory diseases (e.g. COPD), diabetes and many cancers (e.g. bowel cancer, breast cancer) are the number 1 cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In fact, they are cumulatively responsible for 41 million deaths per year, which is 71% of global deaths; 77% of these are in low and middle income countries (WHO)

- Obesity itself is one of the most significant risk factors for non-communicable diseases (a lot more on that in the section below), alongside several others, including tobacco, alcohol and air pollution

- Open Philanthropy and the EA community more broadly have funded several organisations working on several of these other risk factors (e.g. South Asian air quality, Zusha! For road traffic safety) but there is a somewhat perplexing dearth of interest and investment in obesity.

- In fact, I was unable to identify any Open Philanthropy grants on obesity (and only one article on the carbs-obesity hypothesis and one interview focusing on trans fat and food marketing to children), no organisations in the broader EA space, and very little content about obesity on the forum (post, post, peripheral conversation on low obesity rates in EA mentions obesity). There is a chance that I have missed work in this space; apologies if I have, and I would love to hear about it if I have.

- I think this lack of attention to obesity is an oversight, which prompted me to write this report. Unfortunately, I have not had as much time to write this as I would have liked; but in the interest of sharing something rather than nothing, I hope this is helpful.

How big a problem is obesity?

Obesity is defined as a BMI > 30 for adults, and a BMI more than 3 standard deviations above the WHO median for children (WHO). Globally, the 2019 GBD study reports that high BMI contributes to 5.02 million deaths (95% CI 3.22 to 7.11), which represents over 7% of the deaths from any cause (GBD 2019). Further, high BMI contributes to 160 million DALYs (95% CI 106-219). Roughly 60% of this burden is due to obesity (BMI > 30), and 40% due to being overweight (25<BMI<30) (GBD 2019). A significant amount of this burden is due to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and cancer. As noted by Our World in Data: “To put this into context: this was close to four times the number that died in road accidents, and close to five times the number that died from HIV/AIDS in 2017.”

On an individual level, In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults, 39% of all adults in the world, were overweight; 650 million, 13% of all adults in the world, were obese. In conjunction, over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5-19 were overweight or obese in 2016 (WHO, 2018). In fact, most of the world’s population now live in countries where being overweight and obese kill more people than being underweight.

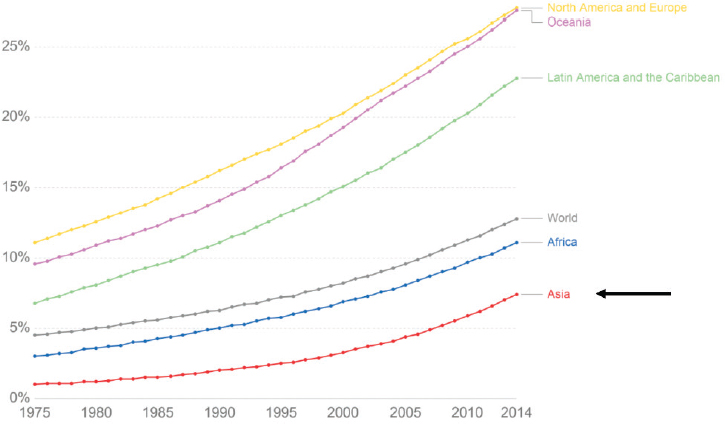

In conjunction with hopefully quite clearly being a very significant scale issue, and perhaps most concerningly, the rate of obesity is rapidly increasing. In the last 30 years, rates of obesity have more than tripled (González-Muniesa et al 2017). This is in part driven due to rapidly increasing rates of obesity in middle income countries, especially those within the Asia Pacific region. In fact, it seems that middle income countries, in the last decade, have seen a particularly significant rise in rates of obesity; more details on the burden of obesity by country are in the following paper from Dai et al 2020

Proportion of the world with obesity over time

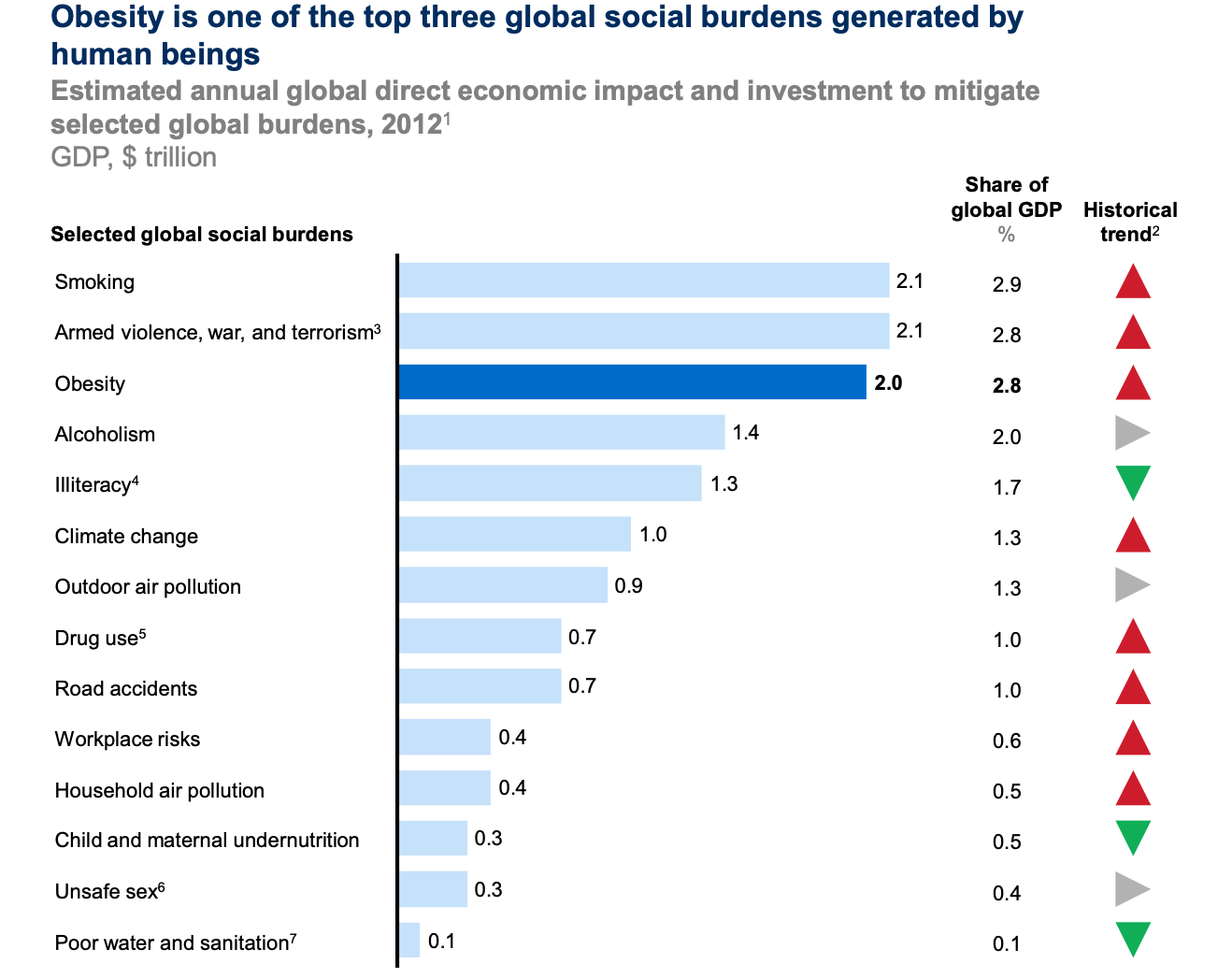

In addition to the health cost, the economic and social costs of obesity are significant. Although our estimates here are less robust, a recent pilot study (Okunogbe et al 2021) has estimated the economic impact of obesity at between 0.8 - 2.4% of annual GDP in eight countries. For instance, in the UK, Frontier Economics estimates the social annual cost of obesity in the UK at around £58 billion, equivalent to around 3% of the 2020 UK GDP. Economic costs for an individual may be between US$2000-7000 per year (Tremmel et al 2017), According to a McKinsey report from 2014, the direct economic impact of obesity is the third highest of any social burden, behind smoking and armed violence & war, but above illiteracy, climate change, outdoor air pollution, road traffic accidents and undernutrition.

Can we actually prevent and/or reduce the burden of obesity, and how cost-effective could it be?

There do seem to be a number of potentially very cost effective interventions to reduce the burden of obesity. For this section, I predominantly relied on the following reports’ estimations - McKinsey 2014 report, the Harvard CHOICES cost-effectiveness study (Gortmaker et al 2015) - as well as a few other sources.

Based on them, health policy interventions are likely to the interventions that are most-cost-effective and beat the ‘bar’:

- Media restrictions on advertising for high calorie products ($50/DALY). In particular, banning TV advertisements for energy-dense and nutrient poor food and beverages during children’s peak viewing times seems to have a cost-effectiveness of $2-7/DALY (Magnus et al 2009).

- Excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages- Although there isn’t that much cost-effectiveness of policy campaigns in this space, this intervention itself is cost saving and generating (Gortmaker et al 2015, Long- et al 2015)

- Price promotions- restrictions on promotional activities e.g. 2 for 1, for high calorie food and beverages ($200/DALY)

There are many things that are unlikely to be highly cost-effective, I have just included some examples below

- Active transport ($31 000/DALY)

- Healthy meals ($14 000/DALY)

- Surgery and pharmaceuticals ($5 000- 1 000 000/ DALY)

Overall, it seems like advocacy for regulations and policies might be an extremely cost-effective intervention; it seems unlikely that other interventions would meet the bar, although this could deal with more rigorous research.

How neglected is it?

It is difficult to assess how neglected this space is; in lieu of a exhaustive comprehensive assessment of this space, I will offer some broad heuristics which I have garnered from my global health work in the space, and from some light research:

- There are lots of organisations working on obesity prevention; a substantial proportion of this is spent on pharmacological weight loss interventions, which are not likely to be the best buy cost-effectiveness wise. In fact, estimates of this tend to be quite high, ranging from $20 000/QALY up to above $1 000 000/DALY (Lee et al 2019), including for new GLP-1 receptor agonists (Hu et al 2022)

- As mentioned above, there are a number of predominantly preventative policy interventions that are really cost-effective; it seems like there are some organisations and funders in this space, but it seems like there is moderate absorbency here. The main big philanthropic funder in the space is Bloomberg, who are doing food policy programs (policies to promote healthier diets) and sugar-sweetened beverage tax advocacy. They have committed over $435 million to help public health advocates and experts promote policy change.

- Given that the rate of obesity is increasing at an increasing rate and there has not been a commensurate increase in funding and interest in this space, I expect investment in obesity reduction to have a high counterfactual value.

Overall, although I didn’t investigate this thoroughly, and despite the fact that there are some major funders in this space, I would be moderately confident that cost-effective obesity interventions are overall still neglected.

Is it tractable to work on?

It is unclear how tractable working on reducing the burden of obesity is and how tractable it is compared to other NCD risk factors (e.g. smoking, outdoor pollution). There are some theoretical reasons why we might think that this is tractable- countries have made pledges to reduce obesity, it is not a prohibitively costly or difficult space for organisations to enter, and I anticipate that funding would not be a major issue given that it is a significant global problem.

However, despite this theoretic evidence that obesity interventions should be tractable:

- Countries haven't done a great job- all countries are significantly off track to meet the 2025 WHO targets on obesity, with most countries experiencing an increase in the rate and burden of obesity

- Interventions, particularly policy interventions, haven’t been very sticky - it seems like there are quite a few interventions which either get proposed and then get rejected e.g salt and sugar tax in England, or which are introduced and then reversed not long after. This could be due to multiple factors- perhaps there are strong lobbies against intervention (Clarke et al 2021 suggest this), perhaps interventions aren’t as effective, perhaps these interventions have other negative ethical or economic externalities. I think that the most plausible reason that interventions haven’t been sticky is more likely due to opposition rather than interventions not being effective or having negative externalities but this is a question that I would want to explore more.

What might I fund?

Based on the analysis above, I did a very brief search for organisations that I think are doing promising work. Overall:

- Organisations that I would fund- I have low confidence on the below, and beyond a brief look at the website and available last 2-3 years of annual reports did not dig further into any of the below organisations:

- World Obesity- Works with partner countries throughout the world to meet obesity targets; has quite significant policy partners and successes, and is well-embedded within the global health structure e.g. is partnered with WHO.

- Global Obesity Prevention Center- Research and policy think tank focused on obesity prevention. Although I couldn't find much on the organisation and its track record, I thought that their approach laid out on the webpage above and in their factsheet seemed pretty solid.

- CO-CREATE- organisation working predominantly in Europe ( as well as Australia, USA and South Africa) on obesity in adolescents by partnering with young people to create, inform and promote policies for obesity prevention. I am least confident about the specifics of this organisation and how impactful their work is

- New organisations- Overall, there were not as many potentially effective charities in this space than I would have expected. I would therefore be interested to see new charities, predominantly working on policy for obesity prevention. Potentially interesting focuses for an organisation might be on child and adolescent obesity, or on policy work in middle income countries.

Key uncertainties

- Is this just too intractable?

As mentioned above, it seems surprising that more progress on obesity hasn’t been made, especially considering there are interventions that we know to be highly cost-effective. This makes me think that there are some reasons that make this space particularly difficult from a tractability perspective. I am not sure what they are.

2. Are there non-policy interventions that are cost-effective?

I anticipate that there are many countries where policy work may be quite difficult; this might be due to the opposition from other stakeholders, or due to baseline challenges in policy work within that country. It would be interesting to therefore see if there are any non-policy options that are cost-effective, as these might have greater potential for scalability.

Have you seen the new GLP-1 agonists? They only got approved for obesity last year, and might actually make a dent. The next generation are apparently even better.

Making these cheaper, more available, and with non-needle delivery are all worthy interventions, more tractable imo than the policy steering you described. But I don't know if they need charity, the market is vast.

GLP agonists are absolutely game changers in the obesity medicine space. (I’m a rehab physician with an interest in obesity medicine and recently have been offered positions in obesity clinics, largely to prescribe these medications). Basically clinics do counselling, dietician, etc., but really need physicians to prescribe these medications because they are so effective. Currently available by injection in Canada, but an oral one is coming. The GLP-1 agonist are covered by most insurance in Canada.

CBT for binge eating disorder also seems to have emerging evidence. Teaching people to feel their feelings instead of feeding them is very helpful. In terms of diets, I’ve seen a lot of evidence support low carbohydrate interventions, and I recommend dietdoctor.com and The Obesity Code (Jason Fung) to my patients.

Diabetes/Insulin resistance leads to most of the disability I see, as a disability specialist. I just presented a poster on this at a conference.

Hey Gavin, good question. My intuition is that:

On cost-effective policy interventions, the relevant costs are for us to try to convince governments to adopt them, not the government costs themselves, and the outcomes should be weighed by our probability of success. Government costs can of course matter for the probability of success, though.

Impacts on government spending and revenues would also be outcomes, not direct costs. If I recall correctly, some studies have found that people with obesity (or with diabetes or who smoke) cost less healthcare than average over their lifetimes, although health issues may also cost them productivity. Plausibly these indirect effects are all dominated by the direct effects on people with obesity, at least in the short term.

I think that a major offsetting factor may be the utility derived from eating to excess and the opportunity cost of spending time in exercise.

Though, it probably makes sense to be healthy for individuals (benefits exceed costs), I would think the costs make it a much closer to the margin to be prioritizing mass interventions. Avoiding contracting malaria, for instance, is less likely to have significant personal costs, while providing immense benefits.

Sure, being healthy is a great thing to promote, but I suspect the significant costs involve this from approaching being a super effective cause area.