Author's Note: What follows is an informal argument in favor of longtermism, aiming to persuade an audience who is new to the concept. I originally posted this on my personal blog. I'd like to workshop it here as a resource to start people down a journey of thinking about longtermism. I would love any feedback that you think will improve this post, and ideas about where/how to share it more broadly.

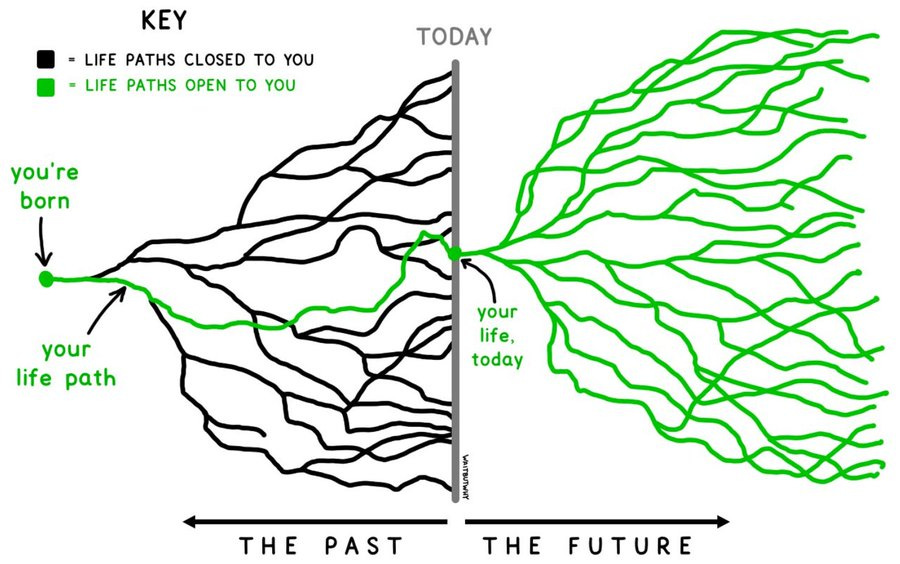

From WaitButWhy, an incredible project run by Tim Urban.

Picture your life so far. Your memories, your triumphs, your disappointments. That time you got in trouble in the first grade for drawing on the classroom wall in bright purple marker. Or the dream you had to be a Pokémon trainer. Or, more recently, the time you saw an old friend in the grocery store and learned they were engaged.

Picture how these discrete moments felt to you—the curiosity of youth, the grief that comes with loss, the quiet joy of a walk in the woods. What was your experience like? How did it feel in your body? Hold in your mind’s eye, for just a moment, the sum total of all these emotions and experiences.

Now, add to the picture all the goals and plans you have for your future. Your plans to go to Montreal next year, or the dress you saw on Instagram that you’ve been saving up to buy, or the takeout you’ve just ordered for dinner. Your career arc, your potential grandkids, your post-retirement condo on the beach.

What do you feel when you look ahead? In total, not for each discrete goal or plan. Add those feelings about your potential futures to the picture you’re developing in your mind’s eye about your life.

If you’re anything like me, it is near impossible to hold all your feelings and experiences and plans in your mind’s eye at once. The enormity of your life spills beyond the boundaries of the present moment, and every time you try to hold that feeling, something shifts, you get a new perspective or remember a different memory.

You also know, deep in your bones, that your life means something (again, if you’re anything like me). That your past experiences, your moments of suffering and joy, your plans and goals, your spiritual connections all mean something. And you might have a pretty good idea of what it all means to you—we humans create meaning in all sorts of ways, from the religious to the somatic to the materialistic, and we often deeply believe and can articulate that sense of meaning. And often we can’t. Either way, if you’re being honest with yourself, you likely know that your life has meaning.[1]

Let’s call this meaning “moral worth.” As a human being, capable of experiences and autonomy and emotions and suffering and planning for the future, your life has meaning. It is “worth” something, morally. What happens to you matters. What you choose to do matters. Not only the sum total of your life matters—every fraction of a second of your life is imbued with moral worth, from birth to death and beyond.

Observe that, already, it is remarkable that you are a being with moral worth. It is remarkable that you are a “being;” nothing ever had to exist. It is remarkable that you are here, right now; you could have never been born for innumerable reasons. Trillions of possible futures are foreclosed every second. If the wind blows in a different direction in Spain one day 200 years ago, your life never begins—you are never even the shadow of an idea. An unthinkable number of events had to go exactly right in order to produce the causal chain that results in your being here at all. And on top of that, it is remarkable that you have moral worth—that your life, your experiences and plans, your happiness and suffering all matter. Already, if you’re anything like me, this is very difficult for you to get your head around.

But wait—it gets better! Picture your family and close friends. Your cousin who never shuts up about the business he wants to start, your father-in-law who cried at your wedding, your colleague at work who brought you a raspberry scone last week when she saw that you were feeling down. You probably know some of their experiences, some of their memories and childhood aspirations, some of their plans for their future, even if you don’t know all of them. You probably don’t know exactly what it is like to be them, but you can guess that it isn’t radically different from what it’s like to be you.

Now, get this: all of these people matter too. They all have moral worth, too. In fact, you might not find it controversial to believe that they all matter just as much as you. You might live your life in such a way as to generally care about yourself more than others, by default, and that’s okay—we all do that, more or less. But you would probably agree, in the abstract, that their lives all matter as much as yours does. On a planetary scale, you have a moral worth of 1, and so does your cousin, and so does your father-in-law, and so does your colleague.[2]

It’s hard enough to hold the meaning of your own life in your mind’s eye; can you hold the meaning of ten, twenty, fifty of your closest family and friends’ lives in your mind’s eye? If you’re like me, it starts to get harder to internalize the enormity of moral worth represented just by my closest friends and family.[3] Your own moral worth, as enormous as it is, is represented on a cosmic scale as 1; now multiply that by ten, or fifty. It’s astronomical.

But we shall soldier on. Expand your circle of moral awareness now to everyone you know and have ever known. The barista who smiled at you the other day, your first grade teacher who got you in trouble for drawing on that wall, the couple you met while backpacking through Europe a decade ago. You probably spend very little time thinking about any of these people, let alone doing things for them. Yet you would probably agree that each of them also has a unique set of experiences, emotions, plans, and values; each of their lives matters as well. Everyone you know and have ever known has moral worth.

Can you still hold all of this in your mind’s eye? At this point, we may be talking about thousands of people, tens of thousands if you’re particularly sociable. Can you truly feel the enormity of the moral worth of all these beings at once? As the saying goes, a single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic. The moral worth of one life (your own) is immense; as we expand our moral awareness to the lives of everyone else, it becomes increasingly difficult to truly know, to feel, their moral worth. It is almost impossible to feel the moral worth for anyone else as viscerally as we feel it for ourselves; this is especially true for people we don’t know well or at all. Let’s call this phenomenon a “failure of moral imagination.”

Of course, there are some benefits to the human tendency toward failure of moral imagination. If one truly understood and felt the moral worth of every other human one knew, it would be nearly impossible to function in modern society. We have to wall ourselves off from other people’s pain; how else could we get through the day?

However, if we conceive of moral imagination as a muscle, it certainly seems plausible that many of us (including, perhaps, you) are not exercising this muscle nearly often enough, even toward the people you know. If you’re anything like me, you forget to call your friend on his birthday. Or you don’t notice the hard time your boss is having. Or you get defensive when your partner tells you that you made a hurtful comment. I believe that these mistakes result from our congenital failure of moral imagination.

If we fail to appreciate the moral worth of the people we know, what about everyone else? Let’s assume that you have met, on the high end, maybe 20,000 people in your life.[4] There are nearly eight billion people alive today. All the people you’ve met in your life represent 0.00025% of the human population. It would take you 400,000 lifetimes to meet everyone alive today. You will go through your life only ever meeting the tiniest slice of existing humans, who all have lives that matter just as much as your life does.

And get this: the vast number of people you will never meet, in your neighborhood and your city and your country and every neighborhood of every city of every other country, all eight billion of them—their lives matter just as much as the lives of the people you know, your close friends and family, and even yourself. Each other living human being has their own set of experiences, memories, emotions, and goals. Each other living human being has the same enormous moral worth that you have.

You might think to yourself that, yes, you know that everyone in the world has moral worth, everyone’s lives’ matter, etc., what’s your point. But do you really know that? Do you truly appreciate how incredibly vast the scale of moral worth of every human life is? Of course not! It’s hard enough to appreciate your own moral worth, let alone that of billions of people you will never meet.

But it’s true. Each person alive today has moral worth by virtue of being human. We have expanded our accounting of beings with moral worth from 1 all the way up to 8 billion.[5][6]

The next time you are in conversation with a high school or college student, ask them what they want to do with their career. You’ll get a wide variety of answers—doctor, artist, engineer, archaeologist, landscaper, etc. But, if you then ask them why they are interested in that career, sooner or later you’re likely to hear that they “want to make the world a better place.” They espouse an altruistic motivation for their life’s work; at some level, they want to give something of value to the world, or at least to the lives within the world that they can influence. Humans are, generally, altruistic; we desire to make a positive influence on other people’s lives most of the time.[7] Even though we have a hard time holding others’ moral worth in our mind’s eyes for very long, we are still motivated, for whatever reason, toward validating that moral worth—treating other people as though we know they matter.

If you’re anything like me, this is true for you too. I want to make the world a better place. That’s one of the key reasons I became a teacher; outside of parents, teachers are famously the people most likely to have a lasting influence on young people’s lives. I want to guide my students to develop critical thinking skills, to expand their sense of the world around them, to nurture their intellectual curiosity and guide them to making a difference with their lives.

I have 150 students a year. If I teach for 30 years, I will have taught 4500 students. That’s a lot! (It feels daunting just to think about…) Some of my students won’t remember my name within six months; others will latch on to something I said, or retain a memory of one of the assignments I gave them, or even have a subconscious awareness of a concept they learned in my class, and they may make choices in the future based on that influence. A few of my students might make profound changes in their lives as a result of my influence, like going vegan or changing their career choice to better help more people. And they will go on to influence the thousands of people they will meet throughout their lives, and so on. And each time, the influence I have on their lives matters as deeply as the influence of my best teachers on my life. Each time I acknowledge and respect my students’ moral worth, it matters.

I am aware of the responsibility that comes along with this influence. But also, I am aware that my influence is limited. 4500 students may sound like a lot, but in a global context it’s next to nothing.

I say all this not by way of bashing teaching, which is as influential a career path as is available to most people. Rather, the point is that changing the world is hard. Making the world a better place is a tall order when you will likely only ever meet and have an impact on a vanishingly small slice of humanity.

Let’s go back to our recently expanded moral circle of 8 billion, the global population at this time. Now, fast forward thirty years. Billions of new people have been born. They didn’t exist before, but now they do.

Should we include them in our moral imagination now, before they are even born? There are good reasons to believe we should. Thirty years ago, many who are alive today (including me!) weren’t born. But we exist now, and we matter. We have moral worth. And choices that people and societies made thirty years ago affect people who were not yet born but who have moral worth now. Our lives are made better or worse by the causal chain that links the past to the present.

Our choices now have the power to influence the future, the billions of lives that will come to exist in the next thirty years. Our choices now affect the conditions under which choices will be made tomorrow, which affect the conditions under which choices will be made next year, etc. And future people, who will have moral worth, whose lives will matter, will be affected by those choices. If we take seriously the notion that what happens to people matters, we have to make choices that respect the moral worth of people who don’t even exist yet.[8][9]

Now expand your moral circle once more. Imagine the next thirty generations of people. So far, there have been roughly 7500 generations of humans, starting with the evolution of Homo Sapiens roughly 150,000 years ago. One estimate puts us at a total of just over 100 billion human beings who have ever lived. The next thirty generations of humans will bring into existence at least that many humans again. Each of these humans will have the same moral worth as you or I. What choices should we make now that will respect their moral worth when they do come to exist?

Earth may be habitable for another billion years. If we scale the entire timeline of possible human life on Earth to 24 hours, assuming we don’t go extinct in the next billion years(!), then the history of humanity to this point represents about 15 seconds and the future of humanity represents 23 hours, 59 minutes and 45 seconds.[10] That’s a lot of people who will be born in the next billion years! That’s a lot of people whose lives will matter, who will have moral worth. Far more moral worth than we can ever truly internalize.

Remember when we agreed that changing the world is hard? Let’s make that more specific. Changing the world—intentionally and in the short term—is hard. But, just as whether the wind in Spain did or didn’t blow 200 years ago influenced the fact of your existence, the choices that we make now influence the world 200 years from now.[11] The choice I make to focus on Kant in my class only mildly influences one student in the short term, but perhaps in the next thousand years, based on the ripples of that student’s inspiration, that choice is somehow causally responsible for an entirely new invention, which in turn influences the lives of thousands or millions more future people. True, most of the time this influence works in ways we can’t explain or even see, but we influence the future nonetheless.

If possible, we should strive to influence the future in a positive direction, because future people have just as much moral worth as we do. Anything less would be a catastrophic failure of moral imagination.

What choices should we make now that reflect the moral worth of these possible future humans, and that we can hope will influence the future intentionally and in the long term? That question is the start of a long journey; for now, simply imagine how crushingly awful it would be if those possible future humans never existed, or existed in a world that was much worse than it possibly could be.

Many an adolescent nihilist has objected to this point. There is no moral value in the universe, and none of our lives ever add up to anything beyond fleeting electrochemical signals on a planet that is a random blip against the backdrop of a dark cosmic eternity. This position represents a bankruptcy of imagination, but while addressing this objection further would be a worthy use of a future piece, it is not within the scope of this one. ↩︎

Here, I’m assuming that each human alive today has identical moral worth, by virtue of being human. This is not universally agreed upon. But I believe it, and it also happens to be easy to explain. ↩︎

Incidentally, this shows up in how I treat my close friends and family differently from how I treat myself. Most of my time is spent taking care of me, doing my job or going to the gym to take care of my body or going to the grocery store to buy my food; in contrast, I am on the phone with my family once every week or two. That’s normal. To live entirely for others is, of course, impossible. ↩︎

This is a back of the envelope calculation; perhaps it’s an order of magnitude higher, or lower. Either way, the point stands. ↩︎

For context: Imagine that you were to take a hike, in order to try to experience the enormity of moral worth in the world. You set out to take eight billion steps. The average step is two feet. By the time you finish with your hike, you have walked the equivalent of the Earth’s equator over 122 times. ↩︎

This obviously excludes nonhuman animals, which I believe to have moral worth but which are beyond the scope of this piece. ↩︎

See Rutger Bregman, among others, for further work on this point. ↩︎

How much do future people matter? The only possible ethical answer I have to this is: exactly as much as present people matter. Some, however, would argue in favor of a discount rate, such that we value future people less the further into the future they are. Climate economics is full of such arguments. On the timescale we are talking about here, however, these arguments are morally bankrupt. Even an infinitesimal discount rate would leave us valuing the vast majority of possible future people at close to zero; in effect, treating them as though they don’t matter. But they do! ↩︎

Once you accept this premise, it becomes nearly impossible to avoid the conclusion that most of one’s choices should be focused on how to most positively influence the long-term future. Tread carefully! ↩︎

And, of course, if we make it that long as a species it is also quite likely that we will have begun colonizing other planets far before Earth’s habitability clock runs out. ↩︎

With the butterfly effect, small changes in initial conditions often have much more influence in the long-term future than the short-term future. I propose that the same is true of our choices. ↩︎

This is great, I enjoyed reading it. Regarding Footnote #8, I would consider mentioning the following example for why discounting makes no sense:

From this podcast.