There's a common claim that the distribution of antimalarial mosquito nets is bad because they are used for fishing. I usually hear this followed by the quick rebuttal "...but I can't imagine who has a problem with enabling needy people to fish!"

There is of course more merit to the objection. A discussion from 2018 on Future Perfect, which in turn cites Givewell's 2015 evaluation of the topic considering overfishing, environmental harms, and inefficient net distribution, but ultimately finding the problems all insignificant. I want to add some discussion of harms not discussed there.

Last year I was in Kenya conducting an interview on commons management, and it came up that people using mosquito nets for fishing was considered bad behavior especially because mosquito nets are fine enough to trap fish fry and juvenile fish, ruining future harvests. This appears to be a widespread and longstanding concern not directly addressed in either evaluation, partly due to lacking academic research now available. The upshot seems to be that thanks to juvenile catch the impact on fisheries is higher than indicated by those reports.

Here is a journalistic report from 2019, which summarizes this 2019 paper attempting to make a direct link to fishery decline in Mozambique seagrass from juvenile catch via mosquito net fishing. They document high percentage of juvenile catch (56%), with caveats as to time of day and year. They didn't provide a baseline comparison against responsible fishing methods (only other comparably unsustainable ones). Nor is a model of how much juvenile catch is needed to noticeably impact recruitment provided. Here's a subsequent 2023 paper I cannot access claiming significant harm to fisheries from mosquito net juvenile catch in Madagascar's coastal coral reefs (the abstract is confusing, so I am suspicious of its quality).

Belief in observable harms from mosquito net fishing seem to be common in affected communities, as per my interviewee, as well as various comments and tidbits sprinkled throughout academic research and news reporting, and in particular this 2022 survey in Zimbabwe. Poverty is usually given as the reason for doing it anyways. This suggests to me the practice is widespread, substantial enough for many communities to reach the same conclusions about its effects, and likely endemic wherever mosquito nets are distributed and fish resources exist.

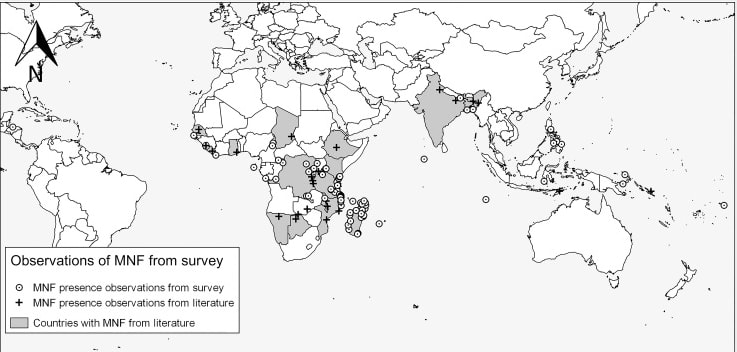

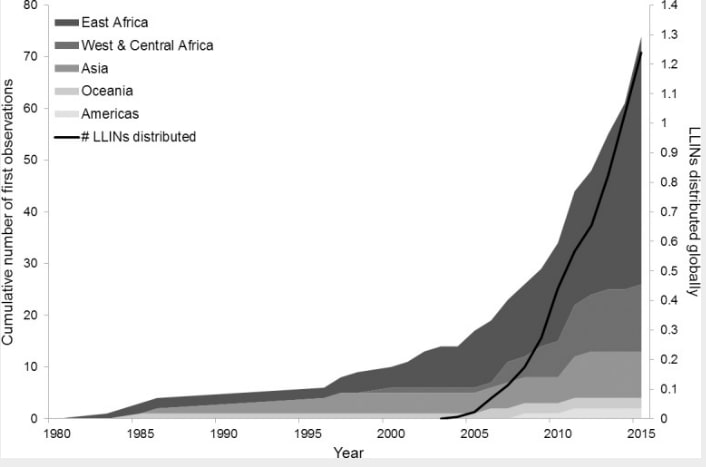

It remains unclear to me from these studies or from any larger meta-studies what the numerical prevalence of mosquito net fishing actually is worldwide and how large and how causal an impact they have on global fisheries. (The best global overview so far, from 2018, is neither quantitative nor exhaustive, and was cited in the Future Perfect article.) But overall it is likely that millions of people mosquito net fish, I infer they do so usually in ecologically fragile coastal and riparian settings similar to those in the above studies, and the practice causes probable impacts to future food security.

In summary there's more evidence that mosquito net fishing causes substantial harm than previously discussed in this community (a harm to commons that is balanced against the harm of immediate hunger, of course). I think this is a relatively small update, unlikely to change my mind about the overall positive benefit of free mosquito net distribution. Work to mitigate the harms caused by mosquito net fishing while maintaining widespread mosquito net access to will probably come from non-EA entities. May also be of interest to ecologically minded readers and fish welfarists.

Thank you for adding this clarification! It's good to determine whether EA-driven funds are unlikely to be substantially exacerbating the issue. Other bednet distributors besides AMF may have worse outcome tracking methods but that is outside of the EA community scope to discipline.

One minor caveat to your clarification is that many of the nets are reused for fishing only after they are considered too worn out for bednet use, at which point even distributors using AMF's methodology may no longer be tracking their utilization.