I've been playing around with Stable Diffusion recently, and an analogy occurred to me between today's AI's notoriously bad generation of hands and future AI's potentially bad reasoning about philosophy.

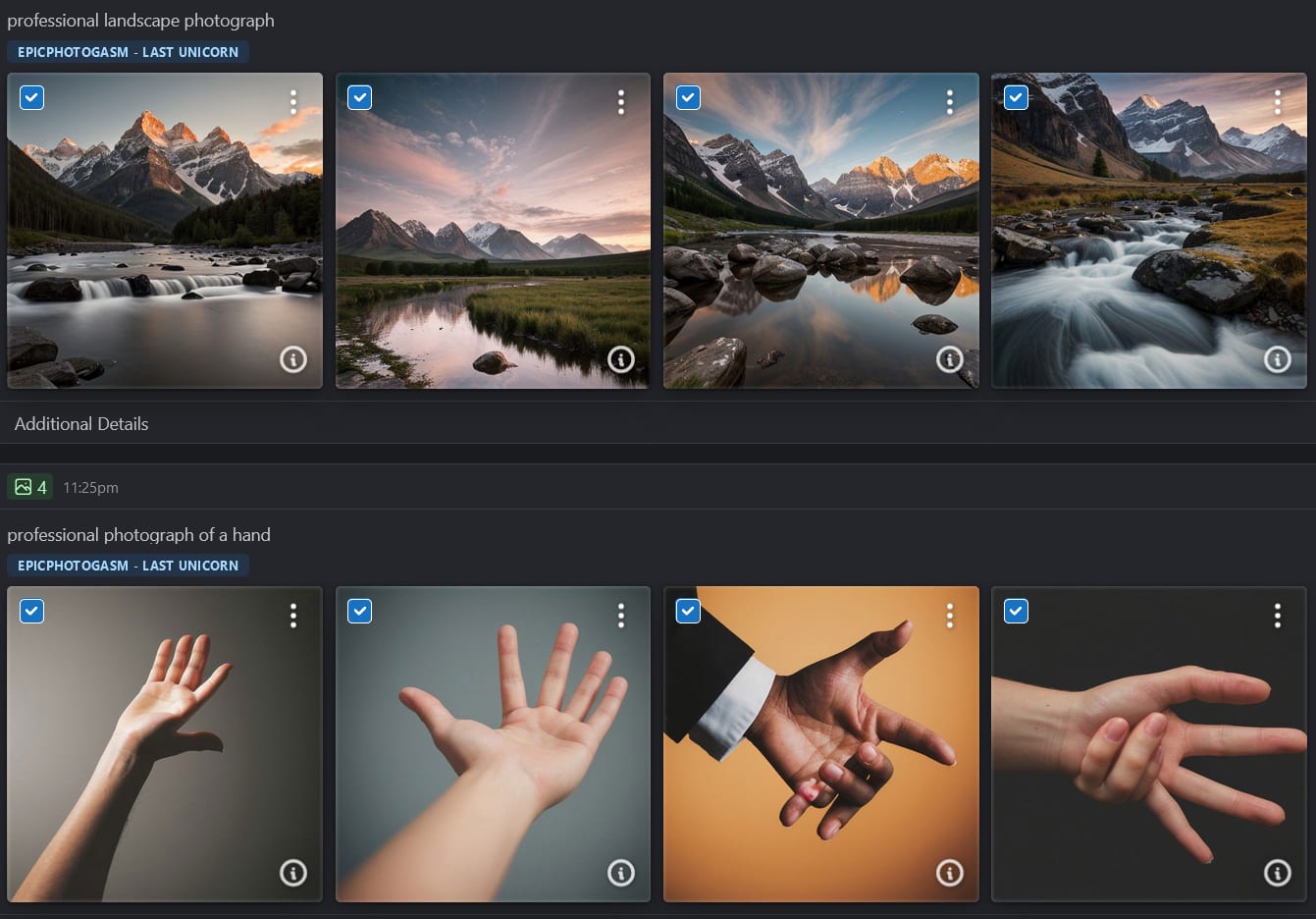

In case you aren't already familiar, currently available image generation AIs are very prone to outputting bad hands, e.g., ones with four or six fingers, or two thumbs, or unnatural poses, or interacting with other objects in very strange ways. Perhaps what's especially striking is how bad AIs are at hands relative to other image generation capabilities, thus serving as a cautionary tale about differentially decelerating philosophy relative to other forms of intellectual progress, e.g., scientific and technological progress.

Is anyone looking into differential artistic progress as a possible x-risk? /jk

Some explanations I've seen for why AI is bad at hands:

- it's hard for AIs to learn hand generation because of how many poses a hand can make, how many different ways it can interact with other objects, and how many different viewing angles AIs need to learn to reproduce

- each 2D image provides only partial information about a hand (much of it is often obscured behind other objects or parts of itself)

- most hands in the training data are very low resolution (a tiny part of the overall image) and thus not helpful for training AI

- the proportion of hands in the training set is too low for the AI to devote much model capacity to hand generation ("misalignment" between the loss function and what humans care about probably also contributes to this)

- AI developers just haven't collected and trained AI on enough high quality hand images yet

There are news articles about this problem going back to at least 2022, and I can see a lot of people trying to solve it (on Reddit, GitHub, arXiv) but progress has been limited. Straightforward techniques like prompt engineering and finetuning do not seem to help much. Here are 2 SOTA techniques, to give you a glimpse of what the technological frontier currently looks like (at least in open source):

- Post-process images with a separate ML-based pipeline to fix hands after initial generation. This creates well-formed hands but doesn't seem to take interactions with other objects into (sufficient or any) consideration.

- If you're not trying to specifically generate hands, but just don't want to see incidentally bad hands in images with humans in them, get rid of all hand-related prompts, LoRAs, textual inversions, etc., and just putting "hands" in the negative prompt. This doesn't eliminate all hands but reduces the number/likelihood of hands in the picture and also makes the remaining ones look better. (The idea behind this is that it makes the AI "try less hard" to generate hands, and perhaps focus more on central examples that it has more training on. I was skeptical when first reading about this on Reddit, especially after trying many other similar tips that failed to accomplish anything, but this one actually does seem to work, at least much of the time.)

Of course generating hands is ultimately not a very hard problem. Hand anatomy and its interactions with other objects pose no fundamental mysteries. Bad hands are easy for humans to recognize and therefore we have quick and easy feedback for how well we're solving the problem. We can use our explicit understanding of hands to directly help solve the problem (solution 1 above used at least the fact that hands are compact 3D objects), or just provide the AI with more high quality training data (physically taking more photos of hands if needed) until it recognizably fixed itself.

What about philosophy? Well, scarcity of existing high quality training data, check. Lots of unhelpful data labeled "philosophy", check. Low proportion of philosophy in the training data, check. Quick and easy to generate more high quality data, no. Good explicit understanding of the principles involved, no. Easy to recognize how well the problem is being solved, no. It looks like with philosophy we've got many of the factors that make hand generation a hard problem for now, and none of the factors that make it probably not that hard in the longer run.

In a parallel universe with a saner civilization, there must be tons of philosophy professors workings with tons of AI researchers to try to improve AI's philosophical reasoning. They're probably going on TV and talking about 养兵千日,用兵一时 (feed an army for a thousand days, use it for an hour) or how proud they are to contribute to our civilization's existential safety at this critical time. There are probably massive prizes set up to encourage public contribution, just in case anyone had a promising out of the box idea (and of course with massive associated infrastructure to filter out the inevitable deluge of bad ideas). Maybe there are extensive debates and proposals about pausing or slowing down AI development until metaphilosophical research catches up.

In the meantime, back in our world, there's one person, self-taught in AI and philosophy, writing about a crude analogy between different AI capabilities. In the meantime, there are more people visibly working to improve AI's hand generation than AI's philosophical reasoning.

Following on from your saner world illustration, I’d be curious to hear what kind of a call to action you might endorse in our current world.

I personally find your writings on metaphilosophy, and the closely related problem of ensuring AI philosophical competence, persuasive. In other words, I think this area has been overlooked, and that more people should be working in it given the current margin in AI safety work. But I also have a hard time imagining anyone pivoting into this area, at present, given that:[1]

A third reason, which I add here as a footnote since it seems far less solvable: Monetary and social incentives are pushing promising people into empirical/ML-based intent alignment work. (To be clear, I believe intent alignment is important. I just don’t think it’s the only problem that deserves attention.) It takes agency—and financial stability, and a disregard for status—to strike out on one’s own and work on something weirder, such as metaphilosophy or other neglected, non-alignment AI topics.

[ETA: Ten days after I posted this comment, Will MacAskill gave an update on his work: he has started looking into neglected, non-alignment AI topics, with a view to perhaps founding a new research institution. I find this encouraging!]

Pun intended.

@Will Aldred I forgot to mention that I do have the same concern about "safety by eating marginal probability" on AI philosophical competence as on AI alignment, namely that progress on solving problems lower in the difficulty scale might fool people into having a false sense of security. Concretely, today AIs are so philosophically incompetent that nobody trusts them to do philosophy (or almost nobody), but if they seemingly got better, but didn't really (or not enough relative to appearances), a lot more people might and it could be hard to convince them not to.

Thanks for the post ! I had read others from you previously, and I think the comparison with the hand generation makes your point clearer.

Precautionary notes : I might have misunderstood stuff, be adressing non-problems or otherwise be that irritating person that really should have read the relevant posts twice.

I sense some possible frustration expressed at the end of the post. In the hope that it is helpful, I would like to explain why this matter is not the one that preoccupies me the most -keeping in mind that I only got a desperate undergrad diploma in philosophy, and just so happen to have spent time thinking about vaguely similar problems (you would definitely benefit from someone else than a random dude giving feedback).

A confusing part for me is that "what makes good philosophy" and the likes is not a hard problem, it's an insanely hard one. It would be a hard problem if we had to solve it analytically (e.g using probability theory, evidence, logic, rationality and such), but as a matter of fact, we need more than this, because non-analytic people are, unsurprisingly, extremely resistant to analytic arguments, and are also a non-negligeable proportion of philosophers (and humans). I think it would be dishonest to claim to solve meta-philosophy while producing assertions that do not move non-analytic thinkers by an inch. Saying stuff that convinces a lot of people is very hard, even when relying on logic and science.

Say that your LLM is trained to do "exquisite philosophy", and that anything it outputs is written in the style of Derrida and shares its presumptions, e.g :

(This is a charitable version of Derrida)

You would like to say : "No ! This is bad philosophy !"

But let's reverse the situation. If a hardcore phenomenologist is faced with the following exchange :

Their answer will be the same : "It's such bad philosophy, that it's not even philosophy!" (real quote).

Of course, when pressed to defend your side, you could argue several things, while citing dozens upon dozens of analytic authors.

But that will not move your Derridean interlocutor -for some obscure reasons that have to do with the fact that communication is already broken. Phenomenologist have already chosen a certain criterion for succesful communication (something like "manifestation under transcendental reduction") while we have already chosen another one. What does it even mean to evaluate this criterion in a way that makes sense for everyone?

I'm also playing naive by making clear distinctions between phenomenal and analytic traditions, but really we don't clearly know what makes a tradition, when do these problems arise, and how to solve them. Philosophers themselves stopped arguing about it because, really, it's more productive to just ignore each other, or pretend to have understood it at some level by reinterpreting it while throwing away the gibberish metaphysics you disagree with, or pretend that "it's all a matter of style".

If anyone makes an AI that is capable of superhuman philosophy, any person from any tradition will pray for it to be part of their tradition, and this will have a very important impact. As things stand out right now, ChatGPT seems to be quite analytic by default, to the (very real) distaste of my continental friends. I could as well imagine feeling distate for a "post-analytic" LLM that is, actually, doing better philosophy than any living being.

So the following questions are still open for me :

1-How do you plan to solve the inter-traditional problem, if at all?

2-Don't you think it is a bit risky to ignore the extent to which philosophers disagree on what even is philosophy, when filtering the dataset to create a good philosopher-AI?

3-If this problem is orthogonal to your quest, are you sure that "philosophy" is the right term ?

Thanks for the comment. I agree that what you describe is a hard part of the overall problem. I have a partial plan, which is to solve (probably using analytic methods) metaphilosophy for both analytic and non-analytic philosophy, and then use that knowledge to determine what to do next. I mean today the debate between the two philosophical traditions is pretty hopeless, since nobody even understands what people are really doing when they do analytic or non-analytic philosophy. Maybe the situation will improve automatically when metaphilosophy has been solved, or at least we'll have a better knowledge base for deciding what to do next.

If we can't solve metaphilosophy in time though (before AI takeoff), I'm not sure what the solution is. I guess AI developers use their taste in philosophy to determine how to filter the dataset, and everyone else hopes for the best?

I wonder if we can few shot our way there by fine-tuning on Kagan’s “Death Course”, Parfit, and David Lewis. Edit: also the SEP?