Addressing global threats globally is critical to securing the long-run future. I argue that understanding the important and often overlooked Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is crucial to understanding how future treaties and international regimes can be structured to counter global threats.

I recently wrote two articles for the think tank CSIS on the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT):

- Has the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Limited The Spread of Nuclear Weapons? Evaluating the Arguments

- Statistically Identifying the NPT’s Effect on Nuclear Proliferation: Is it a Fundamentally Unidentified Question?

I also wrote up two short Twitter threads:

- https://twitter.com/DannyBressler1/status/1372335232574222340?s=20

- https://twitter.com/DannyBressler1/status/1374357787027865606?s=20

I am currently a PhD candidate at the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs, a Global Priorities Fellow with the Forethought Foundation, and I did this work as part of the 2020 Nuclear Scholars program at CSIS. You can see more on my background here: https://rdanielbressler.com/.

Why I Think Understanding the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty is Important For Longtermists

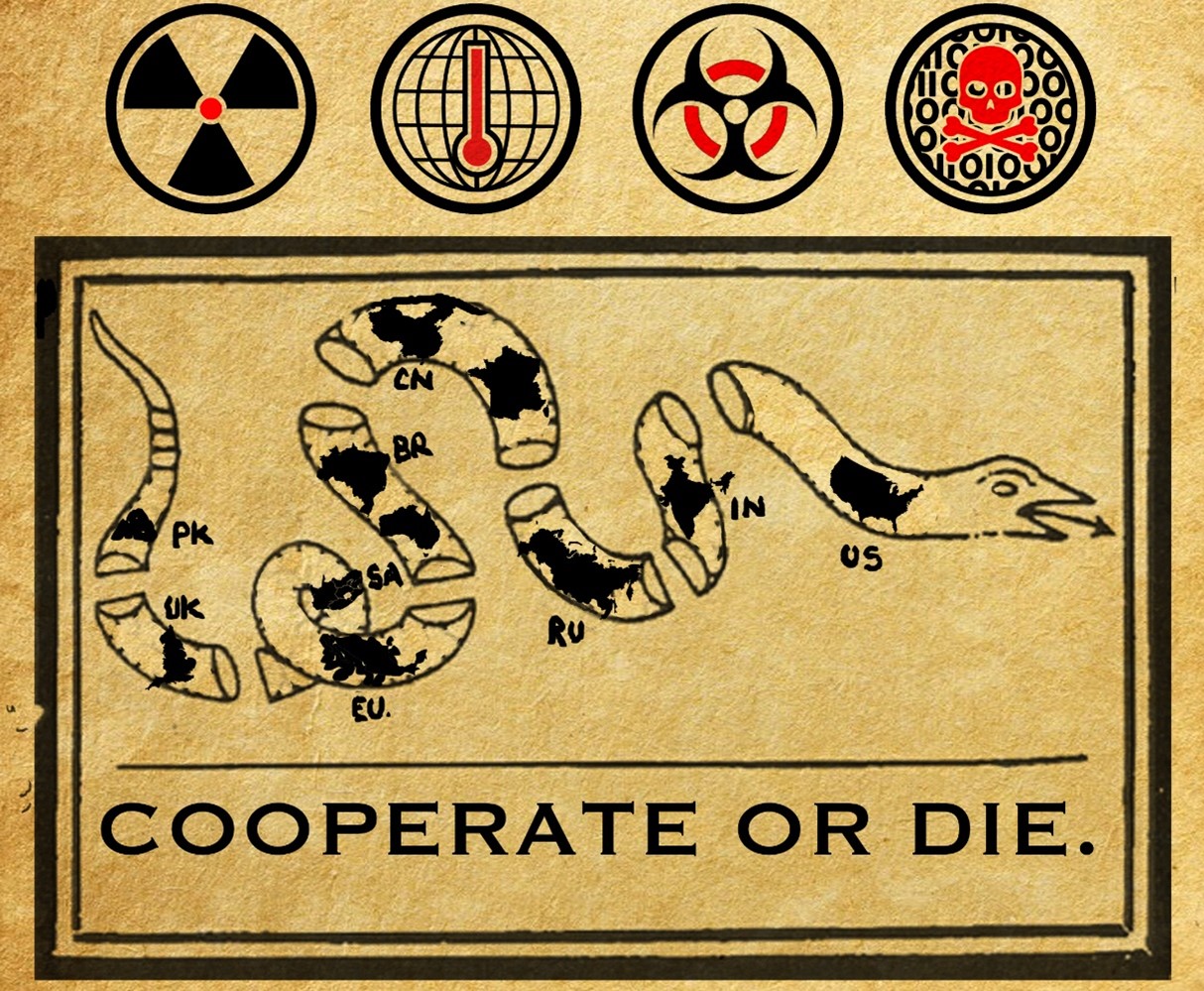

In my view, one of the most crucial factors towards avoiding existential risk and achieving existential security is to achieve strong international cooperation on global issues. My very talented Uncle and I put together a cartoon that tries to convey this point, inspired by Ben Franklin’s famous cartoon:

In practice, achieving cooperation is often elusive because the interests of individual countries on critical issues often differ from what is best for humanity as a whole (my advisor Scott Barrett has a very good book that describes this general class of issues: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Why_Cooperate/zNYTDAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0). To understand how international cooperation can be achieved in the future, it is important to understand if, how, when, and under what conditions it has been successful in the past.

In my view, the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (the NPT for short) is the best historical example of successful multilateral international cooperation on an issue that is hard. Nearly every country in the world is a party to the treaty, making it among the most widely subscribed treaties in the world. In its 50-year history, only one country (North Korea) has withdrawn even though the treaty has an article specifying that countries can leave. The treaty requires countries to conclude comprehensive safeguards agreements that open them to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspection. No country has successfully been able to produce nuclear weapons while subject to the NPT and its safeguards.

My articles provide an overview of the current scholarship that examines if and how the NPT has limited nuclear proliferation (read them to see the details!). I believe that the NPT has limited nuclear proliferation, perhaps significantly, but I think there remains important work to understand how and why the NPT continues to work and under what conditions it may no longer work. I am currently working on a project with Scott Barrett to address this question by constructing a game-theoretical model of the treaty.

There are a wide array of potential global catastrophic risks such as threats related to biosecurity and climate change that are many and increasing in importance. Understanding if, how, and why the NPT has reduced the risk of nuclear proliferation is crucial to understanding how future treaties and international regimes may be structured to counter these other global threats.

A Side Note

If you are interested in issues related to nuclear weapons, nuclear nonproliferation, or nuclear energy, I would highly recommend doing the CSIS Project on Nuclear Issues Nuclear Scholars program that I did this past year. They are generally looking for people that have some background experience/knowledge in nuclear issues (you can see the list of scholars in my cohort here), so I would suggest gaining some of this experience/knowledge ahead of time to be a competitive applicant.

Thanks for highlighting these links! I've now read them and found them interesting. I have a few somewhat vague/broad questions I'd be interested to hear your reactions to:

I ask because I may look into one or both of the first two of those questions later this year, and will probably be involved in setting up a batch of nuclear-risk-related forecasting questions for the site Metaculus soon.

But as I say, those questions are somewhat vague/broad, and I already know of other sources, contacts, etc. - so please don't feel compelled to respond unless you find those questions interesting or already have pre-loaded thoughts.

Thanks for this response!

I'll be quite interested to learn more about Jeffrey's project once it's further along. I might reach out to you or Jeffrey in a few weeks about that.

Regarding the forecasts, we can have any time range and any topic. I already have a bunch of ideas, but just wanted to see if anything bubbled to mind for you independently which I could add to my list. (It's ok if not!)

I guess this might depend what you mean by "particularly reliable".

My understanding is that there's basically just no good evidence either way regarding how accurate and calibrated forecasts are over long time-scales (at least if we restrict ourselves to relevant kinds of forecasts, e.g. ones made by people who seem to have been genuinely trying rather than just making claims for rhetorical/political effect). But there's a little evidence (from Tetlock) to suggest that accuracy may decline relatively slowly after the first year or so. See in particular the great post How Feasible Is Long-range Forecasting?, footnote 17 there, and posts tagged long-range forecasting. Here's the summary of that post:

One other reason why I think that understanding the NPT is important for longtermists: As the world decarbonizes to address climate change (my other big area of research), nuclear electricity generation may increase substantially into more countries, and in particular to countries with lower levels of development/technology. It's crucial to know if the existing nonproliferation regime can ensure that this doesn't cause proliferation, and what sorts of investments must be made to ensure that nonproliferation regime continues to work.

Great post -- and I fully agree that understanding the success of the NPT is hugley interesting and promising, and I also agree with this comment on the importance of this question regarding nuclear energy deployment!

There seems to be one line of thinking according to which almost any facilitating of a country's starting a civilian nuclear energy programme increases proliferation risk and another line of thinking according to getting ahead of the curve in exporting comparatively proliferation-resistant technology might actually reduce proliferation risks in the longer term. The idea behind the second view is nicely expressed by Rebecca David Gibbons in this passage:

"The positive effects of nuclear assistance on nonproliferation suggest a second important policy lesson for the United States and its allies: attempt to regain and maintain a competitive nuclear industry. When US and allied technology is desirable, the nonproliferation regime benefits. Indonesia, Japan, Egypt, and several other states joined the NPT in part to receive nuclear technology from Western suppliers. Today, Egypt is purchasing its nuclear technology from Russia and China and has not agreed to the most stringent IAEA safeguards agreement, the Additional Protocol. If suppliers less concerned with nonproliferation have better technology or offer more favorable agreements than the United States and its allies, the nuclear nonproliferation regime could be weakened." (Gibbons 2020, p. 294)

From: Gibbons, R. D. (2020), Supply to deny: The benefits of nuclear assistance for nuclear nonproliferation, Journal of Global Security Studies, 5:282-298.

Could you outline whether you think this reasoning is compelling, Danny?

Yes, I think it is. There is a literature on whether nuclear assistance and technology sharing for peaceful uses tends to promote or hinder nuclear proliferation, that I mention and cite a bit in my second CSIS piece.