Despite the setbacks, I'm hopeful about the technology's future

It wasn’t meant to go like this. Alternative protein startups that were once soaring are now struggling. Impact investors who were once everywhere are now absent. Banks that confidently predicted 31% annual growth (UBS) and a 2030 global market worth $88-263B (Credit Suisse) have quietly taken down their predictions.

This sucks. For many founders and staff this wasn’t just a job, but a calling — an opportunity to work toward a world free of factory farming. For many investors, it wasn’t just an investment, but a bet on a better future. It’s easy to feel frustrated, disillusioned, and even hopeless.

It’s also wrong. There’s still plenty of hope for alternative proteins — just on a longer timeline than the unrealistic ones that were once touted. Here are three trends I’m particularly excited about.

Better products

People are eating less plant-based meat for many reasons, but the simplest one may just be that they don’t like how they taste. “Taste/texture” was the top reason chosen by Brits for reducing their plant-based meat consumption in a recent survey by Bryant Research. US consumers most disliked the “consistency and texture” of plant-based foods in a survey of shoppers at retailer Kroger.

They’ve got a point. In 2018-21, every food giant, meat company, and two-person startup rushed new products to market with minimal product testing. Indeed, the meat companies’ plant-based offerings were bad enough to inspire conspiracy theories that this was a case of the car companies buying up the streetcars.

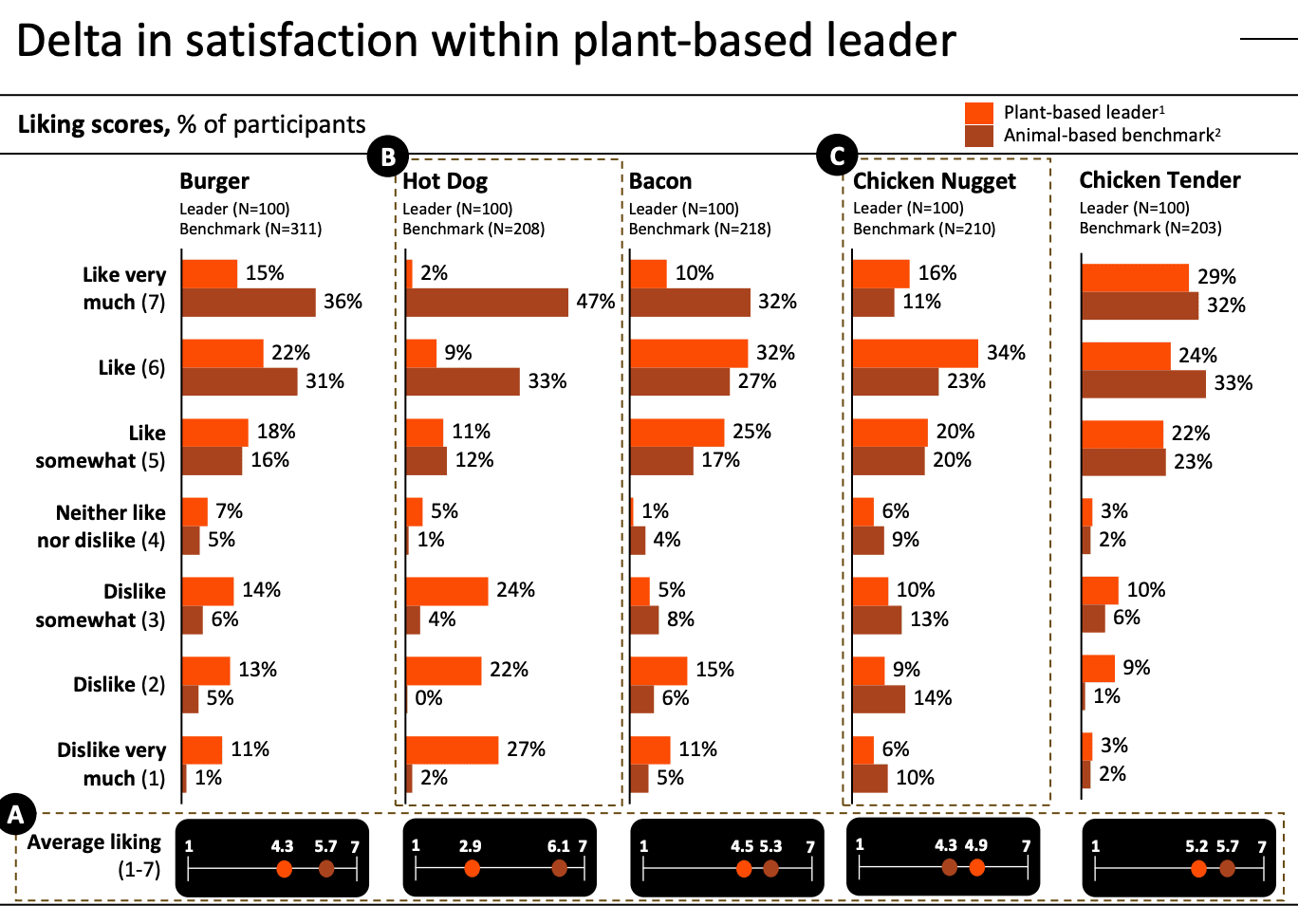

Consumers noticed. The Bryant Research survey found that two thirds of Brits agreed with the statement “some plant based meat products or brands taste much worse than others.” In a 2021 taste test, 100 consumers rated all five brands of plant-based nuggets as much worse than chicken-based nuggets on taste, texture, and “overall liking.”

One silver lining of the plant-based bloodbath is that stores are culling poor products — US supermarkets now average about 10 plant-based meat offerings, down from 15 a few years ago. Only the most popular products have survived. And they’re getting better: 73% of US plant-based meat consumers believe its taste has improved dramatically in recent years.

New taste tests from NECTAR confirm this. Omnivores fed a range of meats from animals and plants still generally preferred the animal variety. But five brands of plant-based nuggets — Impossible, Morningstar, Quorn, Rebellyous, and Simulate — were liked roughly as much as the chicken nuggets, and at least one was liked better (see table below).

This is exciting. Over 80% of Americans consume chicken nuggets every month, spending $2.3B on the frozen variety annually. All nuggets are processed, so the ultra-processed attacks on plant-based nuggets are weaker. The main remaining problem is that plant-based nuggets are much pricier than the animal kind. Which brings us to the role of retailers.

Better merchandising

It’s not surprising that consumers have been slow to change their lifelong habit of buying factory-farmed meat. It’s especially unsurprising when the alternative costs about twice as much. (US plant-based meat eaters say they’re only willing to pay 37% more, while retailers suspect they’ll pay just 10% extra.)

So it’s exciting to see European retailers cutting prices. Four giant German retailers — Lidl, Kaufland, Aldi, and Penny — recently cut the price of their own-brand plant-based meats to match the price of meat. Lidl said vegan sales spiked 30% after the move, which coincided with moving plant-based products next to their animal analogs.

Dutch retailers are going further. Almost all have now pledged to make 50% of their protein sales plant-based by 2025, and 60% by 2030 — up from about 40% today. The largest, Albert Heijn, has launched a new discount own-brand of over 200 plant-based products. Another, Jumbo, recently stopped all in-store and online promotions for meat.

Other retailers are catching up. The UK’s biggest, Tesco, committed to boost plant-based meat sales by 300% by 2025, though it's not on track to do so. France’s largest, Carrefour, has partnered with major food manufacturers to increase plant-based protein sales 65% by 2026. Another big French grocer, Monoprix, launched a new plant-based strategy with the explicit goal to make French diets more plant-based.

If it seems odd to expect retailers to promote a new product category, consider their role in promoting cheap chicken. In 1945, America’s then-largest retailer, A&P, sponsored a competition, The Chicken of Tomorrow, to breed a fatter, faster-growing, cheaper chicken. Almost all chickens consumed today are descendants of the contest’s winner.

More research

We also need more innovation. The plant-based boom from 2018-21 coincided with the introduction of new burgers from Beyond and Impossible that took years and tens of millions of dollars to develop. Today’s investors lack the patience for such timelines, while startups lack the money.

Philanthropists offer a more patient source of research funding. And some of the biggest are newly interested in the area. The Bezos Earth Fund recently funded two new alternative protein research institutes as part of a $100M commitment, while the world’s largest foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, has launched an initiative to boost plant-based innovation.

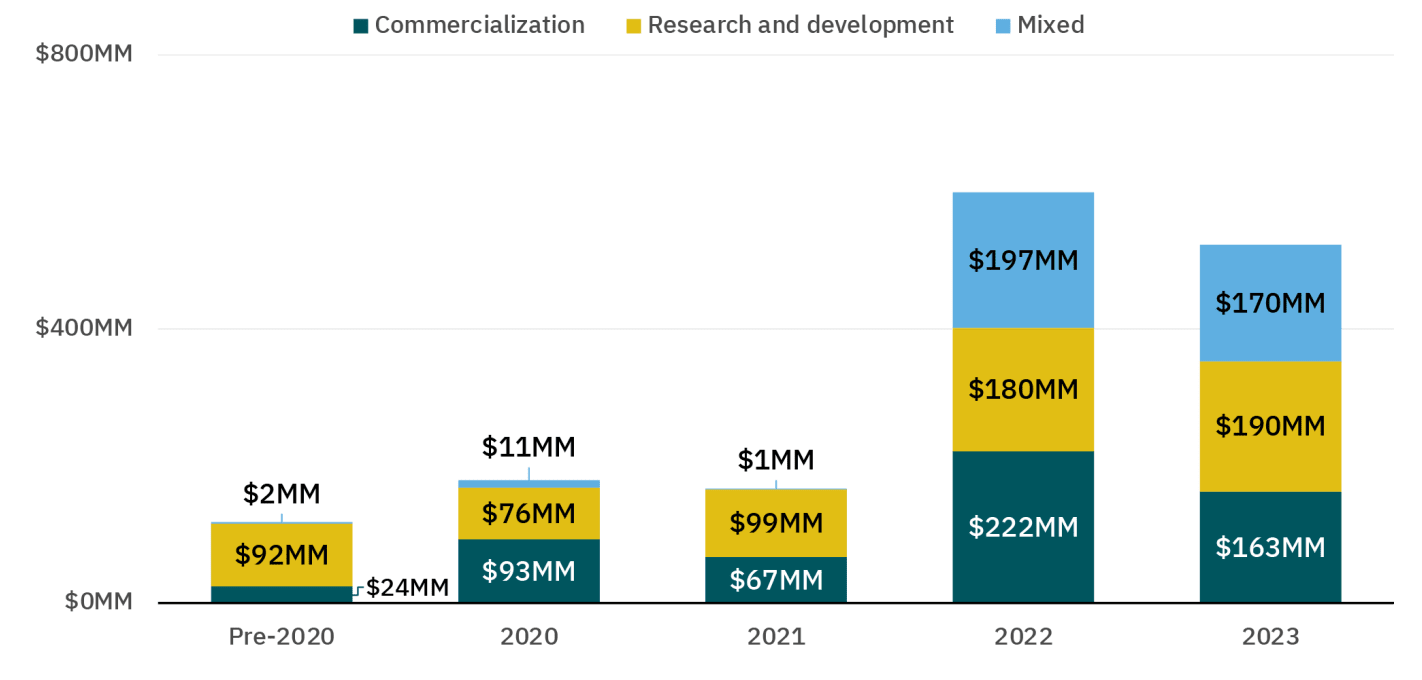

Some governments are stepping up too. Denmark, which has already invested over $200M into alternative proteins, recently launched the world’s first action plan for plant-based foods. The world’s governments have now invested over $1.67B into research and commercialization of alternative proteins — up from just $118M in all years prior to 2020.

That’s not enough. In a similar phase in the development of renewable energy, from 2004-12, my colleague Abhi Kumar estimates that governments invested about $30B in renewable R&D, matching private investment roughly 1:1. By contrast, recent government funding for alternative protein R&D has lagged private investment by about 12:1.

But it’s a good start. A decade ago, almost no government had mentioned alternative proteins — let alone funded them. Today they’re in China’s five-year agricultural plan, the European Union’s protein strategy, the Japanese Prime Minister’s plans, and even the US Department of Agriculture’s research priorities.

A marathon, not a sprint

None of this changes the frustrating reality of the current plant-based market. It will take time to change consumption habits forged over millennia — especially with an incumbent industry ferociously fighting back. But these developments give me hope for the decades ahead.

So too does the course of other transformative technologies. Inventors dreamed up electric cars and solar energy arrays in the 19th Century, and governments funded both from the 1970s on. But by 2010 — despite hundreds of startups and billions spent on research — almost no electric cars were sold in the US, just 0.1% of US energy came from solar, and solar startups were going bankrupt. Today, solar powers about 4% of the US energy market, while electric cars are about 7% of new car sales.

Within our lifetimes, plant-based meat has gone from fringe to mainstream. It used to only be sold at health food stores; now you can get it at Burger King. It used to taste like cardboard; now it tastes like meat. It used to only be for vegetarians and health nuts; now it’s for everyone.

There’s still a long way to go. But it’s far too soon to give up on alternative proteins. Factory-farmed meat won’t get any better. Alternative proteins can only get better. I’m excited for their future.

P.S. If you enjoy this newsletter, you might also like:

- Hive Highlights: insights into updates, news, and opportunities in the farmed animal welfare movement globally from the team at Hive.

- Bold Reasoning with Peter Singer: insights into ethics and animals from one of the founders of the modern animal rights movement.

- Good Signal: insights into alternative proteins from one of the leading investors in the space.

- Understanding Social Change: insights into effective social change for animals from James Ozden.

- Animal Law Europe: insights into Europe’s animal welfare developments from Alice DiConcetto.

- Heads Up: insights into effective campaigning and marketing from Amy Odene.

- Animal Think Tank: insights into strategies and narratives from, you guessed it, Animal Think Tank.

Great stuff!

I am not sure how crucial this is, but I do think this piece gets some of the renewable energy analogies importantly wrong. In particular:

1. The primary drivers of making solar cheap where policies passed in the early 2000s, in particular massive deployment subsidies, not primarily R&D. So, the 30B R&D number for 2004-2012 are unlikely to be a major driver of the dramatic cost reductions in solar, at the same time countries like Germany spent 100s of B on subsidizing solar deployment (see e.g. Kavlak et al 2018, also Nemet's book)

2. By 2010, while solar was still marginal, the cost reduction dynamic was largely triggered through those policies and the virtuous cycle of investment, economies of scale, and China becoming interested in becoming a renewables manufacturing powerhouse. It is not driven by 2004-2012 R&D and it is not really driven by things that started after 2010, more a self-reinforcing dynamic playing out.

Hopefully and plausibly, APs are an easier technology to get cheap than solar panels!

(3. Nitpick: Solar is 4% of electricity, not energy, electricity is only ~1/3 of energy.)

Thanks for the feedback and interesting info! I agree I overstated the importance of 2004-12 R&D. I chose that time period because it felt most comparable to where alt proteins are at, but I should have clarified that earlier R&D was more important.

I based my assessment of the importance of govt R&D policies to reducing solar prices on this IEA analysis -- mostly the graphs showing their assessment that govt R&D policies (both publicly-funding and market-stimulating policies) drove ~two thirds of solar cost-reductions from 1980-2012.

But you clearly know more about the broader literature here than I do. And the IEA's analysis may be consistent with yours if their "R&D: market-stimulating policies" category includes deployment subsidies. Either way, thanks for the thoughtful reply!

Apologies for my delay here.

There is indeed no contradiction -- solar got cheap through massive public support, first mostly R&D and later deployment subsidies / market creation policies in the hundreds of billions.

So the lesson from solar is definitely that public innovation support massively matters, it is more that different forms of support are most critical at different times (that is something the Kavlak paper emphasizes, how at early TRL R&D dominates and then later induced demand becames the major source of cost reduction) and that the R&D money cited is a small contributor to the cost reductions observed then.

If APs were like solar, I think we should expect things to take a lot longer and require a lot more support and maybe the current plateau would be like the 1980s for solar. (But I think there are good reasons to be more optimistic).

One thing that I think is missing from the AP discussion is the potential application for the waste/seconds of EA food in making materials.

The milk and nut fibres of the 1940s and 1950s struggled with feedstock consistency. This was one of the main things the makers of Ardil struggled with. With synthetic methods of protein production this issue would largely solved. No more bad harvests stopping production.

I see altenative proteins as a feedstock for food and our materials industry. Two birds, one stone.

Great post ! Very clear and explains well why just looking at the situation right now is far from enough.