Mental health diagnostic system: In need to redefine mental disorders in line with recent scientific evidence

This essay was submitted to Open Philanthropy's Cause Exploration Prizes contest.

If you're seeing this in summer 2022, we'll be posting many submissions in a short period. If you want to stop seeing them so often, apply a filter for the appropriate tag!

Defining the problem

Mental health problems are not decreasing and therefore are causing suffering all over the world. One in eight people live with a mental health condition.[1] Depression is the leading cause of lives lost due to disability.[2] Suicide is the fourthest common cause of death among young people around the world.[3] Even though mental health is starting to get more attention and funding, it is still a neglected cause area around the world, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Mental health problems have adverse consequences in many areas in life and the burden of suffering piles up especially on vulnerable and marginalized populations.[4] The earlier the problems are addressed the better the treatment results and the less people suffer.

Although mental health conditions are better recognized nowadays and therefore treatment methods are improving, I argue that the underlying way we define mental health disorders does not promote the development of effective treatment interventions. The mental health diagnostic system has been categorical since its beginning days. The most recent diagnostic manuals are ICD-11 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases)[5] and DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders)[6], also known as “the bible of mental health disorders”. Here I list a few issues that these widely used categorical systems have faced.

Predictive validity

The way mental disorders are now defined and classified does not tell almost anything about the trajectory of the mental disorders, especially for the most severe mental disorders, such as major depressive disorder, psychosis and bipolar disorder.[7] Research has supported the view that mental health disorders are dimensional and mutable rather than categorical and stable. The criteria which determine whether a person suffers from a particular mental disorder is mainly based on cross-sectional observations of prolonged and chronic symptoms of clinical samples of middle-aged adults.[7] Because the decision is made by the expression and severity of the symptoms in the present moment, these diagnostic criteria are not applicabe for young people who suffer from symptoms that may still be less stable and not as well-defined.[7] For example, it has been estimated that people who have subthreshold psychotic symptoms but don’t get any preventive treatment, mental health services miss 95% of the people who will develop psychotic disorder later in life.[8]

Because a mental health problem is characterized as a condition to be treated only when the symptoms of the disorder are already severe and present, people who are at-risk yet under the diagnostic threshold will not get appropriate treatment. The majority of mental health disorders occur as early as childhood or adolescence[9] and this contrasted with the years of delay until the first contact to mental health service is worrying.[10] For example, according to WHO’s World Mental Health Survey the median delay of seeking initial treatment for mood disorders ranges from 1 to 14 years.[10]

The clinical utility of categorical systems

Many patients fall short of any criteria in DSM-5 but still need help due to severe impairment and suffering. They then receive a diagnosis “not otherwise spesified” which does not tell too much about the condition and therefore makes it difficult to provide the right kind of treatment.[11] In addition, it is common that a person has many co-occuring psychiatric diagnoses.[12] The categorical manuals are treating disorders as independent categories even though research has systematically supported the view that symptoms usually overlap from different disorders. Many disorders perhaps even have the same underlying psychopathology.[13] We should move on from researching the categorical conditions to exploring the common underlying factors of mental health problems. Mental disorders that are currently classified as such may not be the ultimate truth, as research keeps on fundamentally rewriting the way we think about mental health.

Among psychiatrists the most common reasons for using the DSM-manual were insurance purposes and practice requirements while the least important were to use it in regard to prognosis, patient management and understanding the patients’ challenges.[11] This is not at all in line with the primary purpose of the use of these classification manuals, that is, to provide a helpful guide to clinical practice.

Natural occurrence of mental disorders

Because the symptomatology under a same mental disorder can be very heterogenous and unspesified, people who receive the same diagnosis can actually have very few symptoms in common with each other.[12] For example, it is possible to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder in 227 different ways![14] How should we research depression and its aetiology, when there are a whopping 227 different ways to experience the disorder? Are we really even talking about the same phenomenon when the variety is so major?

On the other hand, people with the same symptom can receive very different diagnoses because of the overlap between symptoms in different disorders.[13] To summarise, the current classification system should not be a basis to the research and clinical practice if it is in fact in conflict with the real phenomena experienced by people.

Why this cause area over others?

Importance

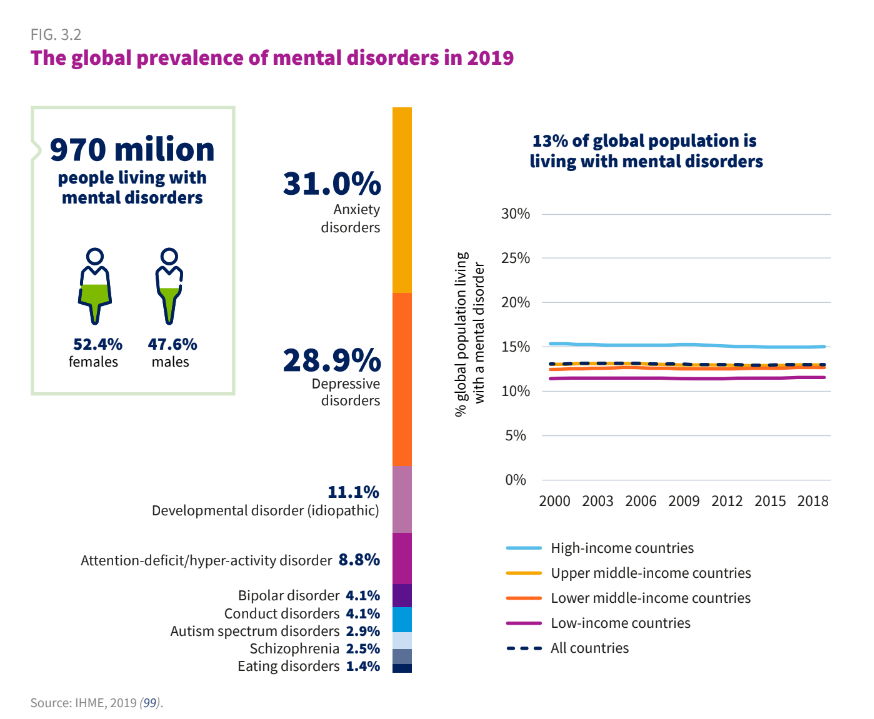

970 million people live with mental disorders (Figure 1). Depression and anxiety are the two most common mental disorders, and these two alone cost USD 1 trillion the global economy every year.[1] The cost of all mental health conditions to the global economy is approximately USD 2.5 trillion and that number is predicted to climb to USD 6 trillion by 2030, which is more than the researchers projected for the costs of cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease combined.[3] Over 80% of people with mental disorders including substance abuse disorders live in low- and middle-income countries.[15] People who suffer from severe mental health conditions, including bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia have life expectancy that is a staggering 10 to 20 years lower than the general population’s is.[3]

Mental health problems cause deaths directly and indirectly. For example, mental health disorders can often be the underlying or causal factor in developing an unpreventable physical condition, such as cardiovascular or respiratory disease.[3] Additionally, many physical conditions may come with mental health problems as adverse physical health also affects psychological wellbeing. On top of that, mental health conditions increase the risk of commiting suicide. Suicide accounts for more than 1 in 100 deaths globally.[3] There are approximately 20 suicide attempts to every one death.[3]

Figure 1. The prevalence of mental disorders has remained the same over time.[3]

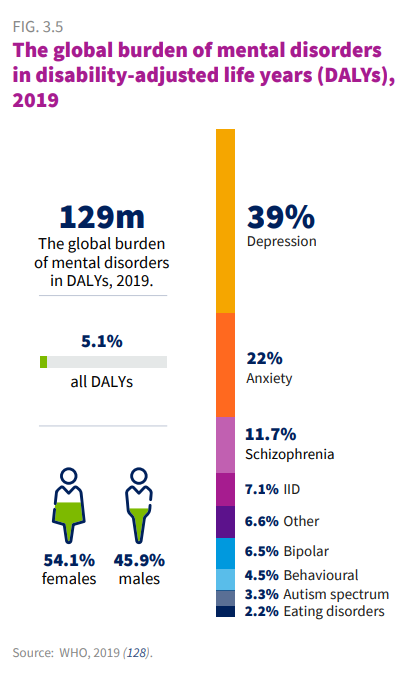

Figure 2. Burden of disease studies estimate the population-wide impact of living with disease and injury as well as dying prematurely. Mental disorders accounted for 5.1% of the global burden.[3]

It is of utmost importance to keep in mind that all these statistics can probably just a preview of the actual prevalence of mental health conditions as stigma, shame and prejudice are still strongly present all over the world and many people do not talk about their own mental health problems.

Neglectedness

The global median of government health expenditure to mental health is less than 2% of which two out of every three dollars is spent on running psychiatric hospitals.[3] This illustrates the entirety of the problem quite well; people don’t get help early enough and hence their symptoms get worse. Since treatment is not preventative enough, there is a huge need for acute care. Thus, psychiatric hospitals are the top priority in regards of financing. Psychiatric hospitals and specialized psychiatric care should be the last resort both for economical and individual reasons.

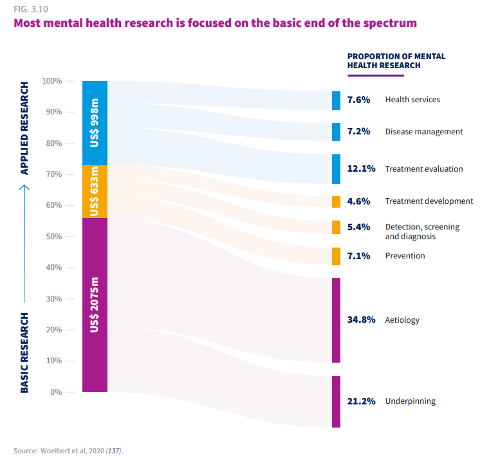

Only 4.6% of global health research focuses on mental health which is mostly basic research, not applied and clinical (Figure 3).[4]

Treatment methods for children and adolescents are basically non-existent or at least very rudimentary even though most mental health disorders occur during that time. For example, there are only 0.01 mental health workers per a population of a 100 000 children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries, and only 19.9 even in high-income countries.[4] Another harsh statistic is that 71 % of people who suffer from psychosis do not get access to mental health services. Also, only one third of the people with major depression disorder get appropriate treatment, even in high-income countries.[3]

Tractability

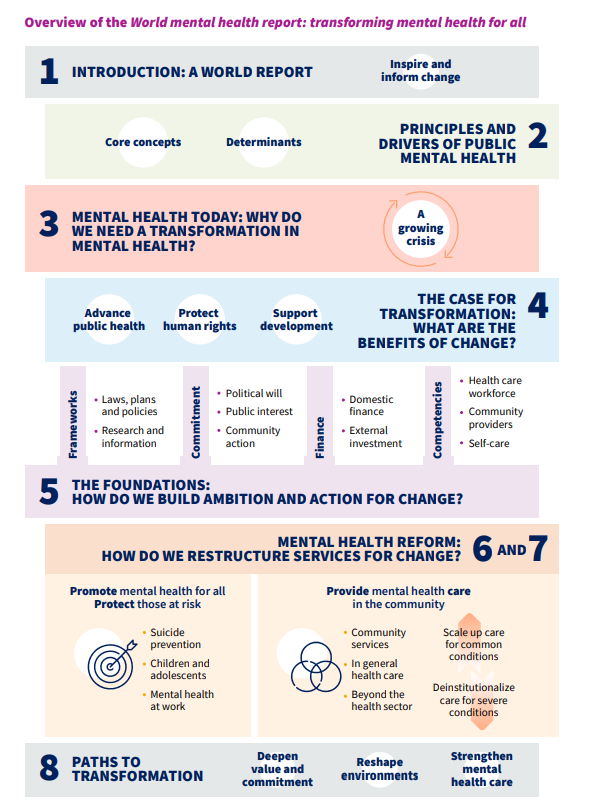

As the World Mental Health Report indicates there is a need to transform mental health services and systems (Figure 4). In order to protect those at risk and prevent the development of disorders, the way people are now being treated as well as the way mental health disorders are considered should undergo a drastic change. I argue that we should move from categorical viewpoint to a more dimensional way of thinking. Additionally, mental health services should consider children’s and adolescents’ mental health as many of the first symptoms already occur during that time.

RDoC

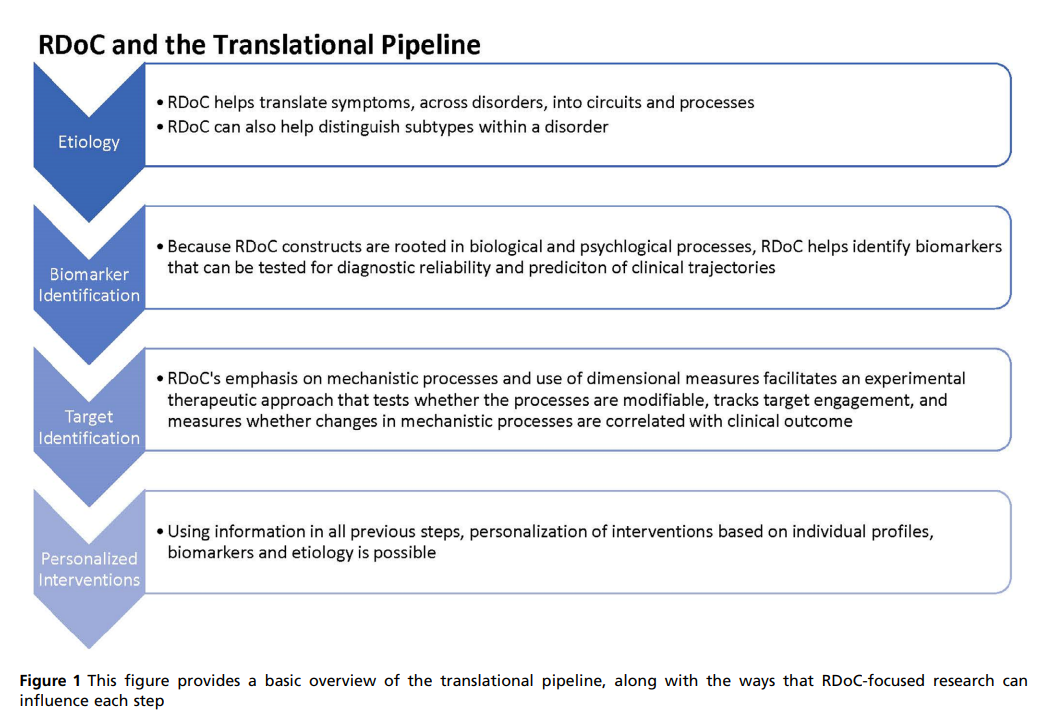

There are at least two research frameworks that aim to promote a change in the way mental health disorders are categorized. The first one is the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative which was launched in 2009 by The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).[16] Its goal is to promote new research approaches beyond the current categorical system and to improve diagnostic manners, along with the prevention and interventions for mental health problems (Figure 5). As this new research paves the way, the goal here is to start applying methods into clinical practice. Some trials have already been carried out, for example trial considering processing speed training in adolescents and young adults who possess a high clinical risk for psychosis.[13]

HiTOP

Another research framework in this field is called HiTOP (The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology). It aims to reorganize the symptoms and pile them together as broader and more hierarchical dimensions based on empirical evidence.[17] However, in order to get HiTOP into clinical practice, there has to be determination guidelines whether a person needs a treatment. One of HiTOP’s workgroups is called “Clinical Translation”. HiTOP’s mission is to develop a range of different treatment methods that are specially tailored to the set of symptoms at hand as well as the overall psychological dysfunction.12 This tailored treatment can include preventive intervention, psychotherapy initiation, suicide risk assessment and hospitalization. The hierarchical taxonomy is now under research and field trials are being implemented.

Challenges and final words

This is certainly not the easiest cause area to tackle but all the more important. I am not suggesting that the categorical system needs to be completely taken out of use, but rather to update the way mental health problems are addressed based on the recent scientific evidence. I argue that the most important reason why the mental health treatment and diagnostic system should be reformed is because people do not get access to treatment early enough. The long-term suffering that the delay in treatment causes is inhumane. I argue that the delay in treatment is partly due to the lack of interest to reconstruct the mental health system up to date. As I mentioned the “bible of mental health disorders” before, it is now mostly out of date and is no longer serving its purpose when new scientific methods have been developed to investigate the true nature of mental health problems.

My approach on solving the problems concerning the categorical system is based on the desire to prevent mental illnesses. I am well aware that this is not the only concern, nor even the most prominent one, as there is, for example, a major lack of clinicians and mental health services alongside with poor mental health education. Increasing these resources promote the prevention as well. I argue that the progress of coming up with new effective treatment methods is being slowed down by the fact that the categorical division does not recognise the common underlying psychopathology in mental health disorders. How can we develop and improve treatment methods not even knowing what exactly we are treating? Furthermore, how can we effectively prevent children’s and adolescents’ mental health disorders from worsening, when there are no tools to detect the first signs?

There is a lot of scientific evidence of the trajectories and risk factors of mental illnesses, but the evidence is yet to be utilized in clinical practice in a sufficient manner. However, a lot of research still needs to be carried out as mental health problems are very complex and heterogenous among people. There are not unambiguous biomarkers to determine mental illnesses as there are in physical conditions. Even though unraveling the causes of mental health problems is an extensive challenge, that doesn’t mean it is impossible or that it is subject that does not deserve attention. As we see in the WHO reports, mental health problems are a worldwide phenomenon that cause a lot of people a whole lot of suffering. Our health consists of both the physical and the mental and each should receive at least equal attention.

To sum up, people don’t get help early enough for their mental health problems, as the threshold for receiving treatment is receiving a diagnosis. A diagnosis is only issued once the threshold of the diagnostic criteria is exceeded. The problem here is that the diagnostic criteria are based on a categorical system, which accounts for present and severe symptoms of each disorder. What it does not take into account instead is the developing and variable features of mental health disorders. I plead you to be a part of the mental health revolution by funding this cause area. That is, to update the mental health diagnostic and treatment system to be in line with recent scientific evidence. The recent scientific evidence suggests that it would be beneficial to revise the current categorical division to a more dimensional and hierarchical way of considering mental health disorders. Once we comprehend the underlying mechanisms of mental health problems, we have a better chance of developing treatment that is both effective and preventive.

- ^

Mental health. Accessed June 11, 2022. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health

- ^

Mental Health and Development | United Nations Enable. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/mental-health-and-development.html

- ^

World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338

- ^

Mental Health ATLAS 2020. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240036703

- ^

ICD-11. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://icd.who.int/en

- ^

Psychiatry.org - DSM. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- ^

Scott J, Henry C. Clinical staging models: From general medicine to mental disorders. BJPsych Adv. 2017;23(5):292-299. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016436

- ^

Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):251-265. doi:10.1002/wps.20446

- ^

Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar‐Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359-364. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

- ^

WANG PS, ANGERMEYER M, BORGES G, et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):177-185.

- ^

Mullins-Sweatt SN, Lengel GJ, DeShong HL. The Importance of Considering Clinical Utility in the Construction of a Diagnostic Manual. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12(1):133-155. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092954

- ^

Kotov 2021 HiTOP review ARCP.pdf - Google Drive. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JIbBWkZs4-nCjjaZuNA5IMdQWfN5Qt77/view

- ^

Pacheco J, Garvey MA, Sarampote CS, Cohen ED, Murphy ER, Friedman‐Hill SR. Annual Research Review: The contributions of the RDoC research framework on understanding the neurodevelopmental origins, progression and treatment of mental illnesses. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63(4):360-376. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13543

- ^

How many different ways do patients meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder? Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:29-34. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.007

- ^

Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, et al. Mental Health Service Provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632917694350. doi:10.1177/1178632917694350

- ^

About RDoC. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/about-rdoc

- ^

About HiTOP | Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://renaissance.stonybrookmedicine.edu/HITOP/AboutHiTOP