Noah Taylor is a peace educator and researcher who is a member of the core faculty for the UNSECO Chair for Peace Studies at the University of Innsbruck. In this talk, he explores the importance of bridging the field of existential risk with that of peace and conflict studies, and proposes a preliminary research agenda.

We’ve lightly edited a transcript of Noah’s talk for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and read it on effectivealtruism.org.

The Talk

Noah: Hello, everyone. My name is Noah Taylor, and today I will be outlining a research agenda for bridging the fields of existential risk and peace and conflict studies.

For the past 12 years, I have worked in the field of peace and conflict studies, which, broadly speaking, is an interdisciplinary field encompassing systematic research on the causes of conflict, war, and violence, and the conditions of peace. For much of that time, I have worked in the field of peace-process support, where we help develop relationships between hard-to-reach actors, such as the military, non-state armed groups, and governments.

I was tasked with staying abreast of the cutting edge in the field of peace and conflict theory, as well as building theory from lessons learned by networks of peace practitioners. Throughout this work, [the seed of an idea] started to form in my mind. I could clearly see how a theory in the field of peace and conflict studies was helpful in guiding [current] actions and interventions. I saw how this theory helps us understand and work with the past. But I saw very little that dealt with the question of the future, both in the academic realm and from [surveys of] practitioners themselves.

I started to become interested in the fields of existential risk and emerging technologies. Given the importance of the questions raised by these two fields, I was perplexed that [those questions received little attention] in the field of peace and conflict studies. My hypothesis is that both fields can benefit from the lenses of the other — peace studies through the future-oriented, long-term lens used in the field of existential risk, and existential risk through the lens used to examine the complexities of peace and conflict.

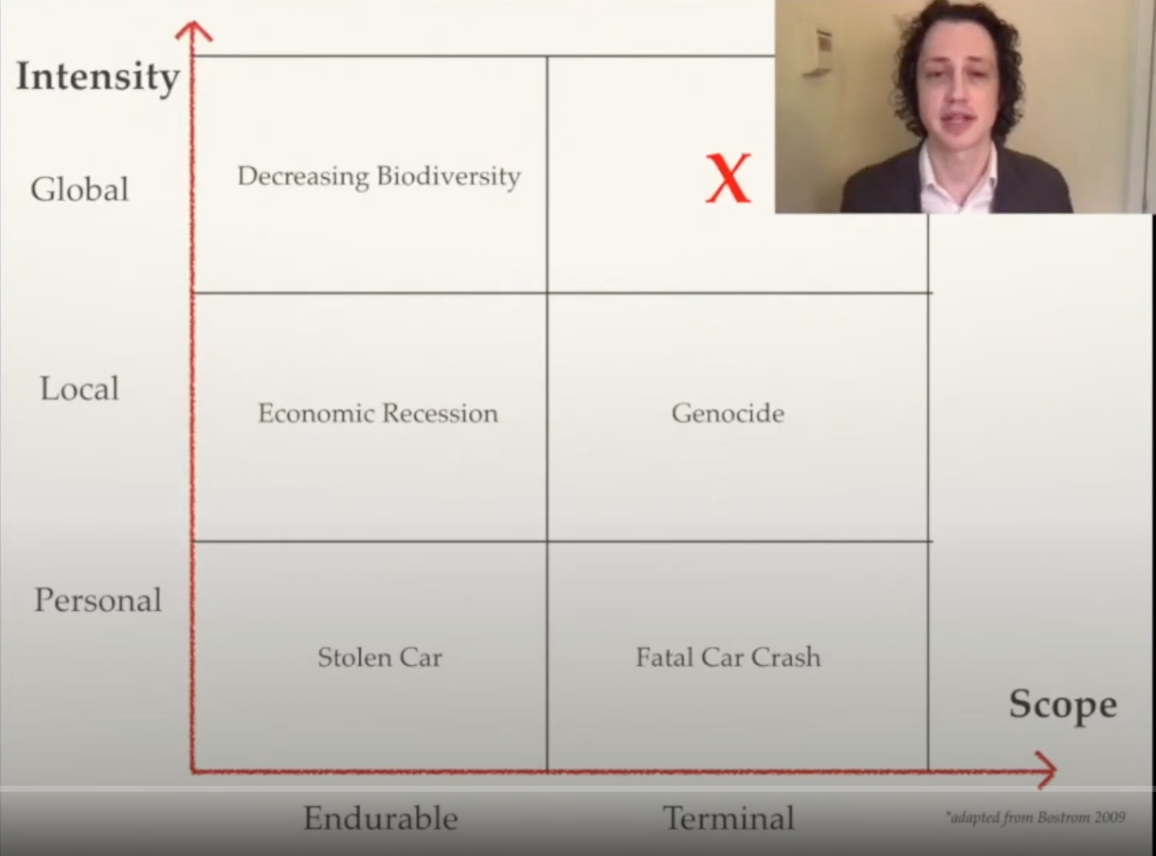

Existential risk frames the context of my research problem. It can be understood as an event or phenomenon where adverse outcomes can permanently and drastically curtail human potential.

We can look at risks in terms of their scope (that is, the size of the group at risk), their intensity (how badly the group would be affected), and their probability (our best current estimate of an adverse outcome). What I'm interested in is what happens when the scale is global and the scope hits “terminal” (where the X is in the slide below).

Many risks of global concern and intensity are endurable. This doesn't mean that waning biodiversity, moderate global warming, and global economic recessions would not cause untold misery or suffering. But at the global level, if these levels are transitory, they are endurable, in that there will be a possibility of recovery. With existential risks, there is no such possibility. Beyond the possibility of extinction, these risks curtail our ability to flourish.

What I am proposing is mapping out an initial set of research priorities for bridging the fields of existential risk and peace and conflict studies. An initial stage of mapping will be important for several reasons:

1. Both existential risk and peace and conflict studies are expansive fields. In seeking to bridge them, we need to determine a set of priorities of research.

2. The knowledge needed to accurately assess these linkage points goes well beyond the scope of expertise of any single researcher — and will thus require the cooperation of a network of scholars and practitioners.

3. Because of the rapid rate of change and learning, such an effort will require large-scale collaboration.

As a starting point, it will be important to figure out which questions are the most important ones to ask, how these questions should be prioritized, and, of course, how they could be answered.

From surveying the literature in both fields, I propose four initial lines of inquiry:

1. Great-power conflict

2. Pandemic, peace, and conflict

3. Climate change, existential risk, and conflict

4. Emerging technology

These four research lines follow sets of questions that concern the relationship — either direct or indirect — between conflict and issues of existential risk. In each, there is a more nuanced articulation and prioritization of the sub-questions as needed.

Let’s take a look at our first line of inquiry, the question of great-power conflict. Here, we look into the likelihood of conflict between, for example, the United States and China. If such a conflict were to occur, how likely is it to pose an existential risk? Also, what types of interventions, de-escalation, trust building, diplomacy, or other safeguards are likely to be the most effective at reducing the most risk? These questions will then break down [based on] the nuances of the relationships of the different factors in the constellation. For example, if a great-power conflict is not likely to be an existential risk itself, to what degree does it contribute to other risks, such as the use of weapons of mass destruction?

Our second line of inquiry is the interrelationship between disease, peace, and conflict. We have seen how protracted violent conflict can lead to the destruction of health and sanitation infrastructure, and the effects this can have on public health. Recently, we have seen the vast array of effects that a global-scale pandemic can have on our understanding of security. In this line of research, we would seek to untangle this web of relationships and develop answers to questions such as “To what degree does a global pandemic contribute to or exacerbate violent conflict?” and “Where do public health and peace-building measures most effectively overlap?”

Our third line of research is structurally similar to our second, and seeks to uncover the complex relationships between climate change, conflict, and existential risk. We are starting to see the influence of climate-change sensitivity, and how this is likely to make certain kinds of conflict more likely. We could also extend the examination of these variables to look into ways in which conflict and climate change form an insidious feedback loop that makes them more likely to become an existential risk.

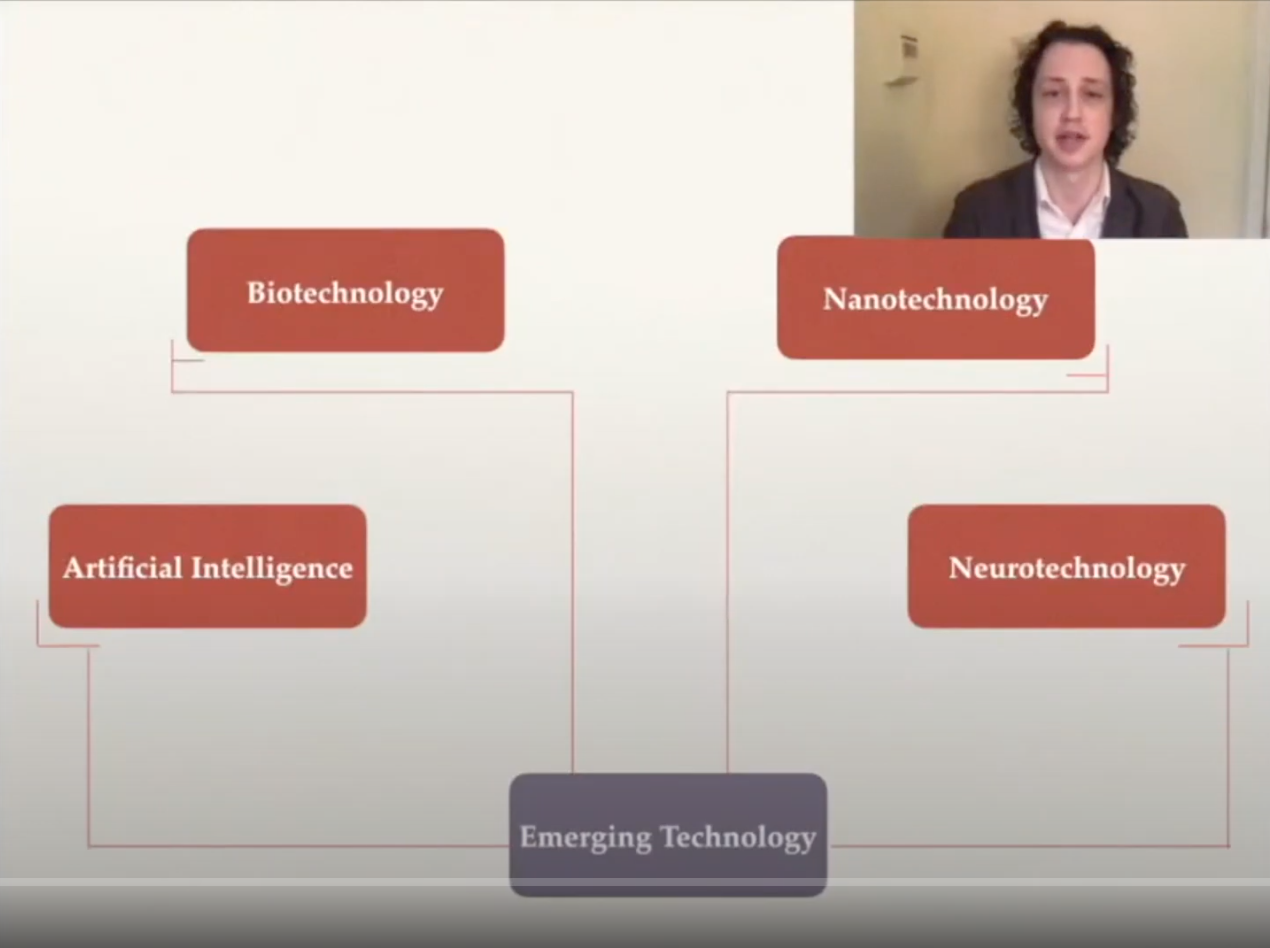

Our last line of inquiry revolves around the interaction between emerging technologies and peace and conflict studies. Emerging technologies are those whose potential is not fully recognized or yet understood, and are characterized by their novelty, fast growth, persistence, coherence among different research streams, wide range of impacts, overall uncertainty and ambiguity, and potential scale of impact in the near future.

Our key emerging technologies of focus are artificial intelligence, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and neurotechnology. We'll take a brief glance into each of these four areas.

In the field of artificial intelligence, we can see questions around the ethics and regulation of autonomous weapons, and concerns about the possibility of an AI arms race and the use of AI technologies in mass surveillance systems, as well as questions related to the future of work.

In the area of biotechnology, advances in gene editing, such as CRISPR-Cas9, allow us to edit the genome and germ line of already-living organisms. This brings into question our genetic future and how we want to shape it, as well as the security around many gain-of-function experiments — particularly those associated with the H5N1 virus. We may also begin to question the ease by which one may be able to resurrect a virus, such as the Spanish flu, and call into question how these issues may lead to a restructuring of the types of actors and the scale of violence that can be waged.

In the area of nanotechnology, we're seeing the possibility of developments that rival the philosopher's stone. Techniques such as mature molecular manufacturing may allow us to produce anything from anything else, [and we don’t yet know what effects that might have].

Finally, in the realm of neurotechnology, we see the possibility of dramatic cognitive enhancement and the questions surrounding the access to these technologies, as well as questions surrounding the boundaries between human and machine beginning to blur.

With these four research streams, I proposed an initial set of research tools.

First, I proposed the use of elicitive conflict mapping as an orienting framework.

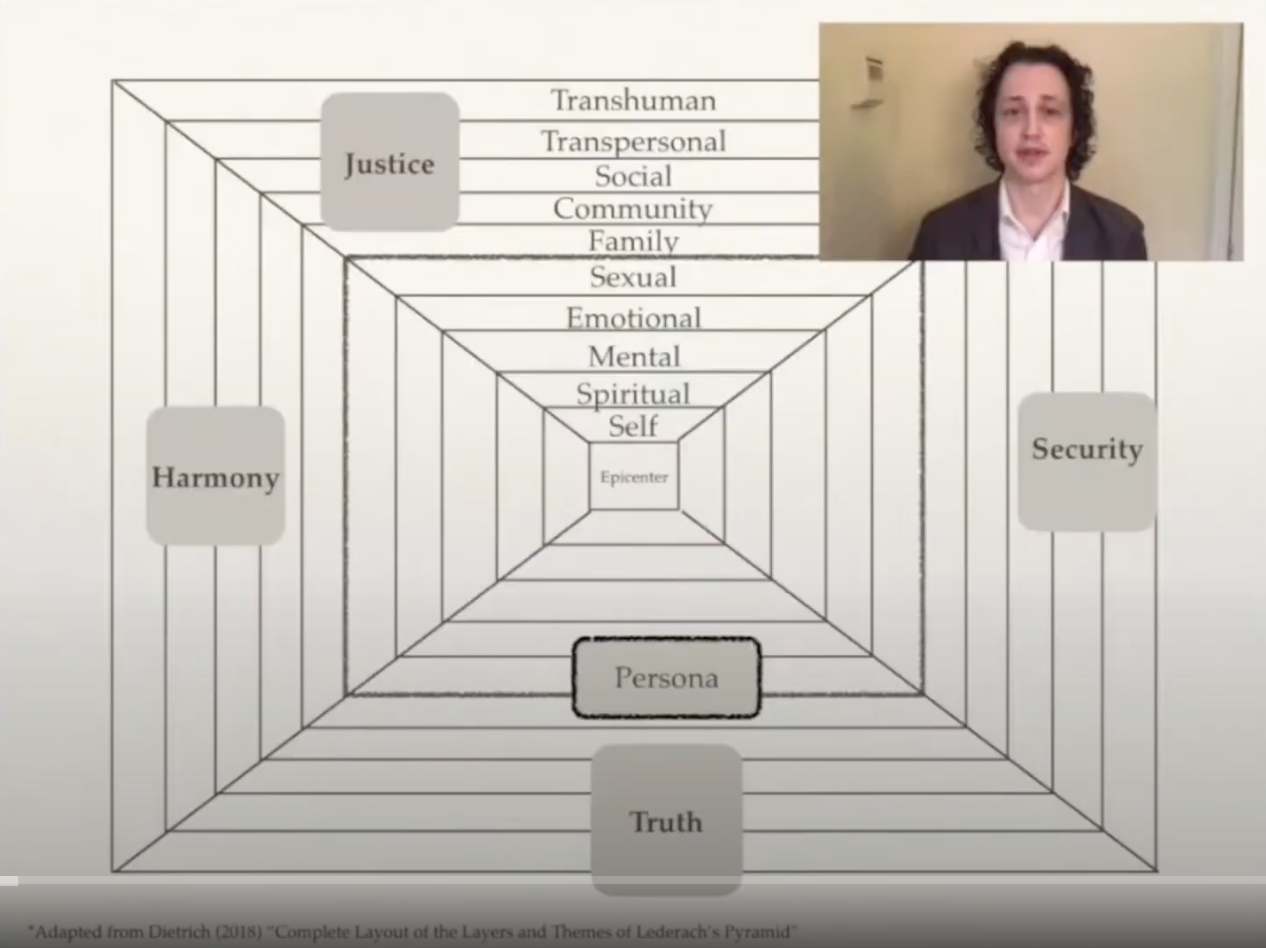

In brief, elicitive conflict mapping was developed by the UNESCO Chair for Peace Studies, and is oriented around four general categories of understanding peace. These are: (1) peace through justice, (2) peace through balance, (3) peace through truth, and (4) peace through security.

Look at how these understandings [interact]:

Our second tool would be a review of the existing literature in both fields with these key questions in mind, bringing a lens of peace and conflict studies into the literature surrounding existential risk, and conversely, bringing a lens of existential risk into the literature of peace and conflict studies.

Our third tool would be expert elicitation. This has already been widely deployed in the field of existential risk and emerging technologies. It involves structured approaches, such as the Delphi method, for surveying thought leaders in this field in order to get an accurate picture of what possible trends are emerging, or may emerge in the near future.

Finally, [we recommend] the use of systems analysis methods, such as those developed by Collaborative Learning Projects in the UK. These are methods of applying systems theory to issues of peace and conflict in order to determine what may be the most effective entry points to transforming conflict.

This endeavor is still in its infancy and may lead to a large-scale research project or the foundation of a research institute. My hope in bringing it here today is to see how these ideas resonate with the larger effective altruism community, and to receive feedback and ideas from a large community with diverse sets of knowledge and life experiences. I thank you for your time, and I welcome any questions and feedback.

Barry: Thanks very much, Noah. That was a fascinating talk. It’s interesting to see how peace and conflict studies fits across so many of the different existential risks that we talk about in the EA [effective altruism] community. I imagine the audience members are relatively familiar with the field of existential risk and the work being done by organizations like the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge.

But perhaps what audience members aren't so familiar with is the field of peace and conflict studies. Could you tell us a bit more about what that community looks like, who the key players are, and what's happening in that space?

Noah: Sure, and thank you for that introduction, Barry. The field of peace and conflict studies, as a codified or distinct field, is relatively new, starting maybe in the 1960s. But of course, we've been concerned about issues of peace and conflict since probably the beginning of human civilization.

We can see the field evolving out of international relations and the difficulties in forming international relations after the first World War, and not being able to stop the second World War from occurring, and then seeing the horrors that came out of it. Therefore, peace thinking originally came out of international relations and maintained a lot of that perspective.

Then, it became influenced by a combination of peace movements — in the work of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, and all of our famous peace activists, as well as a lot of the peace church traditions, such as the Quakers and the Mennonites. Then, in the 1960s and 1970s it started to be influenced by humanistic and transpersonal psychology, which brought a much more relational lens to the field.

I think we're about to hit a new moment in the field of peace and conflict studies where we will hopefully bring together many more perspectives than we had in the past.

I think if we were to look for the main trends in peace work, we could conceptualize it in terms of conflict management. This would be the idea of dealing with conflict from a great-power perspective — that we're just managing conflicts and trying to keep violence down. Usually, those who have a monopoly on violence and the ability to use power are responsible for that, versus those who maintain more of a conflict-resolution approach, [viewing] conflict not necessarily as something to suppress, but as a problem to be solved. These are the approaches that we see in negotiation and mediation.

More recently, we’ve [seen] this perspective which we call “conflict transformation,” which sees conflict as not necessarily bad, but an engine of change. The idea is to take more of a facilitative approach in order to [shift] conflict away from violence, and toward building a more peaceful and sustainable future.

Barry: Fantastic, and are there any particular institutions around the world that are seen as the leading institutions in the field?

Noah: Certainly, there are few. Probably the first one is the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), which came out of Johan Galtung's work of codifying peace studies as a distinct field. You can also see a more quantitative approach in Sweden at the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, where they crunch all of the numbers [available on] conflict in order to [predict] trends.

Then, there are other organizations. For example in the UK, there's the Collaborative Learning Projects Association, which is oddly abbreviated “CDA.” They have done a lot of practitioner research in order to look more specifically at the question “How do we know if peace work is effective or not?” They try to base that analysis on findings from practitioners in the field doing peace-conflict work.

Barry: Wow, that's fascinating. Is there any strong evidence about particular interventions that do help to reduce conflict?

Noah: This is one of the difficult issues to unpack in the field of peace and conflict studies. If you take a very short-term approach with your view of peace work, [outcomes like] getting parties to the table to discuss a peace agreement, sign it, and implement it, can more or less be measured. You can look at cease-fire violations and you can track them across time.

But if you want to explore how a conflict has been dealt with over the span of 20, 30, or 40 years — or take a multi-generational perspective — it becomes quite complex. Similarly, if we change our perspective from looking at outbreaks of direct violence to looking into the structural or cultural forms of violence, then the question of determining effectiveness becomes much more complex.

I think that this is one of the areas where the field really needs to expand and bring in more people who are skilled at quantitative analysis to bridge the social sciences and humanities with some of the more predictive techniques that we find in the EA community.

Barry: That sets me up nicely to ask about the main focus of your talk: how we can bridge the two fields of existential risk and peace and conflict studies. What challenges have you experienced in trying to bring together those two fields?

Noah: I think that there are several layers of challenge. One has to do with something I already mentioned: bringing a lens of longtermism into the field of peace work. You normally find that this lens is more about values. [We often frame] peace work [in terms of] “working from the 200-year present.” In other words, everything you do in a conflict intervention is related to [what happened during the previous] 200 years, and should be thought of as influencing 200 years in front of you. It’s a nice idea and a good way of emotionally or spiritually orienting yourself. But in terms of what that means practically, in terms of [considering] timelines, it becomes much more difficult.

A second level of the challenge is that very little peace work is solely peace work. It's often in a different frame — such as development, peace building, or peacekeeping. And much of this work is tied into program funding cycles. So, even though you may have an ideological vision of peace work as a “200-year now” [activity], you need to write your proposal at the beginning of the year to get funded, and then do your reporting at the end of the year. How do we balance that?

I think the third level of the challenge [relates again to] long-term thinking. It can be quite easy for peace practitioners to develop a myopic view of dealing with conflict. When you are [in the midst of] an active conflict, it can be so overwhelming that the only thing that matters to you in that moment is the here and now. This is understandable, of course, but the question is: How can we build the space for peace practitioners to [step back and] take a more expansive view of how they might extrapolate what they see in the field into what might be coming in two, three, five, 10, or 15 years?

Barry: Wow, that's fantastic. Thank you, Noah. So I'm going to move to our first audience question now. Ian asks, “Do you find a new cold war between the US and China likely?”

Noah: I think this is a tremendously important question, given how the geopolitical scene has unfolded in the past few years. Part of the answer [depends on] how we define the conflict that is arising. I think that it's quite unlikely to see a “hot conflict” in the traditional sense, but I do wonder if the frame of what a cold war is will change. I think our previous experience of cold war is often a proxy conflict being fought in Africa or in Latin America, but I don't think the frame necessarily encapsulates things like cyber warfare or information warfare or economic warfare.

What I understand about the Chinese approach to peace and conflict issues, and also their approach to development, is to never go directly against the opposition or what is perceived to be the opposition, but to find ways around it. Therefore, I think that part of how we will go about answering this question is by expanding our understanding of what that conflict would look like, and how we would know when it is happening.

Barry: What do you think the broader implications are for US-China relations, in terms of long-term risk?

Noah: I think one of the potential issues of a great-power conflict is not necessarily that it is an existential risk in and of itself, but it can be a contributing factor on so many levels to all kinds of conflict, as well as to suffering, misery, and a lack of opportunity and growth.

I think that this also calls for us to be creative in the ways that we approach peacebuilding. One of the main mitigating factors that we saw in the previous experience of cold war is the connections made on “Track 2” diplomacy [peacemaking through conflict resolution via non-governmental actors] or “Track 3” diplomacy [peacemaking through commerce] between the US and the former Soviet Union. How do we build connections between academics, peace workers, and those involved in different forms of NGO work or peace-building work? How might we find more creative, easier ways for countries to work together [outside of the typical] adversarial frame?

For example, one of the only ways that peace-building work is currently ongoing between the US and North Korea is in very small farming projects. It's the only way to get grassroots peace workers into the country to also learn from the people about their situation and their own understanding of peace and conflict.

So, I would say that it calls for creativity, and also for establishing connections wherever we can make them.

Barry: So if someone listening to this talk wants to contribute to global peace and stability, do you think it's better for them to work in the military or the intelligence community, or perhaps in the government? Or would they be better placed in the civilian research sector or NGO sector?

Noah: I would say that I understand peace and conflict studies as more of a perspective, similar to how everyone takes math classes, but very few people get PhDs in mathematics. I would say, [follow] your natural inclination or interests. So, if you’re interested in serving in the military, I think the idea of the military as peace builders is often under-explored, and there is quite a lot of potential there.

One of the programs that I work on with the UNESCO Chair [for Peace Studies] [at the University of] Innsbruck in Austria is to run CIMIC [Civil-Military Cooperation] trainings. It’s about getting civilians and the military to work together. In the current situation of global conflict, there are many tasks that even peacekeeping forces can't do, and that they rely on NGOs to do. But the NGOs also depend on the military or the peacekeeping forces in order to maintain security. Therefore, a lot of our training is focused on how to learn to work together in that way.

Of course, one of the adages in peace studies is always “start locally and learn locally.” So, if you're interested in peace issues, you don't necessarily need to wait until you get a great job with the UN. You can work within your own community. It's amazing how often those learnings scale up. The dynamics of conflicts in your own family, or your own neighborhood or community, aren’t that different than geopolitical conflicts. I think the same main issues and emotions drive them at all levels. With the right kind of lens and the right kind of self-reflective capacity, you can pursue peace work in [multiple ways].

That being said, I do think that one of the trends in peace work is for people to develop both a thematic focus and a regional focus — at least in the beginning. So, if they were studying peace studies or a related field, they might focus specifically on post-conflict issues or gender studies. Then, they might pick a region like North Africa or Southeast Asia. For at least the first five or six years of their career that could lead them into their first set of work experiences. Later, they might expand into either further regions or further thematic issues.

Barry: Thank you. I know one of the big goals for you at this conference is identifying collaborators who can work with you on developing this research agenda. So, could you tell us more about the skills and expertise that you're looking for to help with this work?

Noah: Certainly, and I'm coming from the perspective of peace and conflict studies, as someone who's super-interested in issues of existential risk and aversion technology. I'm a bit of a nerd, so I read a lot of books and watch a lot of YouTube videos, and I'm always listening to a podcast.

I’m [interested in collaborating with] people who are, [first of all], interested in this [topic], but [also] have a bit of expertise in a particular issue. I'm not going to be able to develop the background to understand the complexities of machine learning and AI, or all of the nuances of a biosecurity perspective, for example. So that's where I really look for collaborators. I’d like to draw on their experience in trying to figure out how we can [not only] ask these important questions, but [consider] how to prioritize them.

Barry: Excellent. In terms of prioritizing, I noticed in your talk that you set out a few different models that you use in peace and conflict studies. Could we go into a bit more detail on some of those?

I remember the first one I saw was, I think, the transrational peace philosophy, where you were looking at greater justice and a balance of truth and security. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

Noah: Certainly. I think that this is one of the things that sounds the most esoteric in peace studies, but once it's explained, is common sense. In the UNESCO Chair’s 30 years of research on peace, they started with this question of, well, what is peace? If we're going to work for peace, what is it?

Of course, there's a level where you realize that almost everyone has a different understanding of peace, because peace requires a preceding subject or it doesn't exist. Nonetheless, after doing thousands of interviews, they started to see general categories of how people tend to understand peace. We [prefer to use] the term “peace family” because it denotes a blurry boundary; the categories often overlap.

We talk about the “energetic” understandings of peace, which comes from many different traditions, but are more easily expressed as “peace is balance or harmony.” That’s quite similar to how many people experience peace, but also the way that you would see understandings of peace in many different indigenous traditions, or Taoist or Buddhist traditions.

The “moral” understanding of peace, [on the other hand], is the kind that you see particularly espoused in the monotheistic traditions, where peace is very deeply rooted in a notion of justice.

Then, we see the “modern” understanding of peace built into the modern scientific understanding of the world, and the framework of the “nation state,” in which peace is primarily derived from security.

There is also what we would call the “postmodern” understanding of peace, which is derived from the understanding of plurality of truths.

So, a transrational approach is really just [the notion] that we always try to keep all four of these understandings of peace in our analysis, and [consider] how they are being balanced or not balanced.

For example, in a situation where you have a lot of active armed conflict, the frame of peace is very often [security-driven] — that we need to get the military or the police involved, and we need everything to be secure. But what you'll often find is that a dramatic emphasis on security causes a decrease in emphasis on harmony. Many people's social ties start to become stressed or break down, and many tensions arise in communities. So that's part, in essence, of the idea of the transrational approach to peace studies.

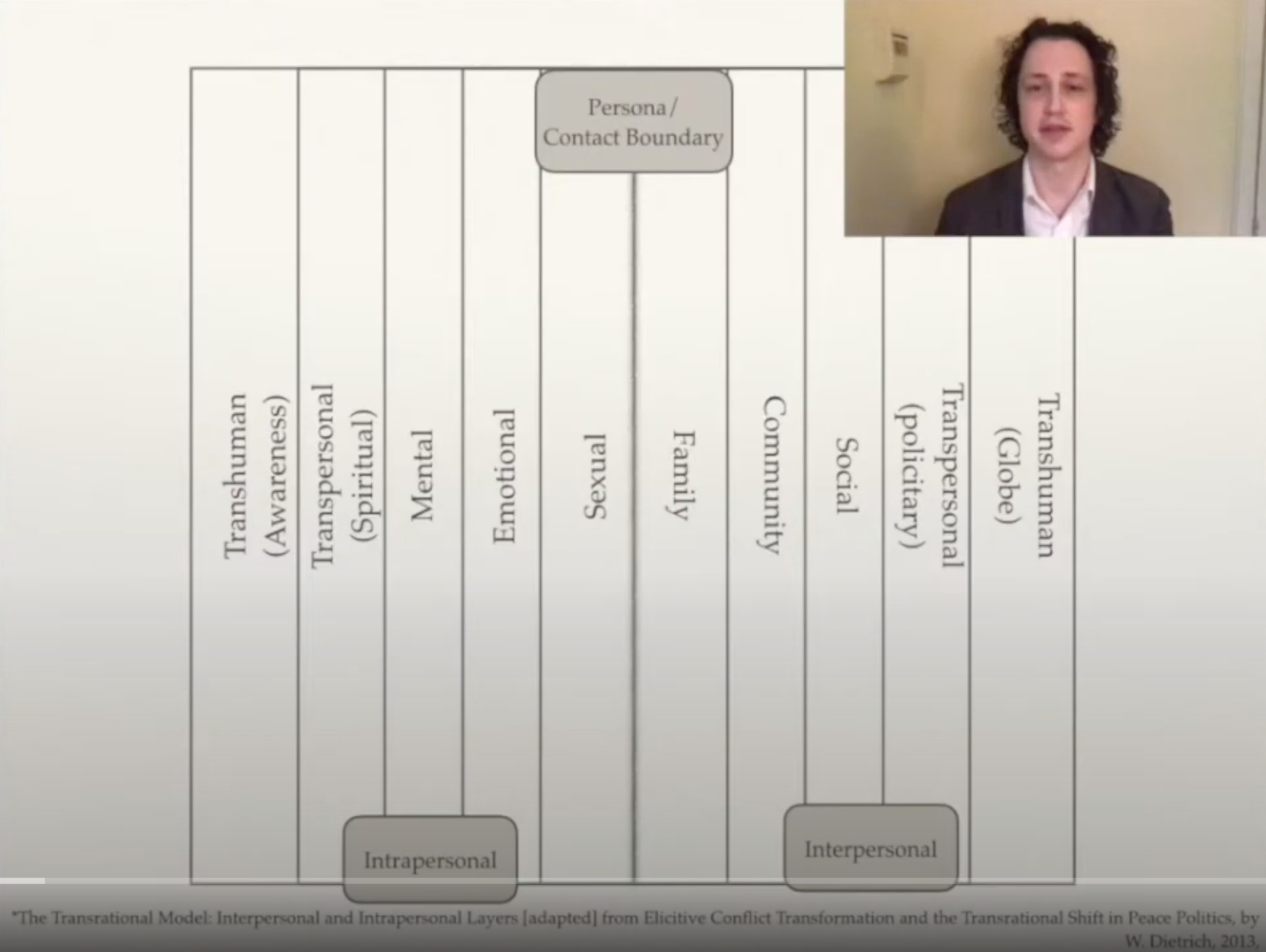

This ties in to the next model that I mentioned, which is elicitive conflict mapping: How do we take everything we know about peace and try to apply it in a method of mapping? Elicitive conflict mapping is designed to be used to unpack a specific episode of conflict throughout these four understandings of peace, but also through multiple levels. And by levels, we could mean: What does the situation look like at the grassroots level, at the middle-level actors’ level, and at the elite-level actors’ level? But there's also this question of how, in each conflict, the different layers of identity interact. How are all of the layers of identity within myself? How do they connect to the layer of interpersonal identity?

An example of that would be when issues of trust or mistrust are prevalent in a conflict situation, you will often find emotions of belonging, or lack of belonging or exclusion. This is what we mean by looking at different layers of the conflict. The elicitive conflict mapping method [involves] using all of these lenses to provide as robust of a picture as [possible] to get a sense of what that moment of conflict is like. It also gives us a sense of where some possibilities for conflict transformation might [lie].

Barry: Thanks for explaining those models in a bit more detail. Let me get back to some of the audience questions now. Jacob mentions that he'd like to see more attention to the risks of conflict leading to some kind of dictatorial lock-in or governance collapse. It's not an existential risk, but we end up trapped in a really bad situation. Have you looked into that area very much?

Noah: That's one of the considerations that I [identified] a year ago, at the outset of this project. It was originally only focused on emerging technologies in peace and conflict studies. [I initially focused on] this framework of existential risk, but I do have this question about how it excludes issues precisely like this. A totalitarian state of governance isn't necessarily an existential risk, but it certainly inhibits human thriving.

There's a great definition of violence by Marshall Rosenberg, who developed the concept of nonviolent communication. He said that the best definition of violence is anything that inhibits human flourishing.

I can see, then, that this exact question [of the collapse of governance] would be a primary question to work into peace and conflict studies. This is something I would like to work on with others. [We could] hammer out the nuances of these questions and their implications [based on] our starting frames of reference, and [determine] which of those frames might be the most useful. Is existential risk actually the best starting point, or is that a more important consideration to address later? Maybe human suffering, for example, is a better starting point, with existential risk becoming a secondary consideration. I would love to hear other people's views on the same question as well.

Barry: Fantastic. If you do have views of that, make sure you reach out to Noah.

Noah: Yes, please.

Barry: Another good [audience] question: How tractable do you think it is to work on great-power conflict? It seems it can be very difficult to predict these conflicts, let alone prevent them from happening. Is there anything we can do as a community in this area?

Noah: I think that there can be a huge feeling of frustration and powerlessness in these kinds of situations. My first introduction to the peace world was trying to work as an activist to stop the US invasion of Iraq. You could just see this whole war machinery being geared up, and public opinion being swayed, and you felt really hopeless.

I think that the first step is, of course, to find a way to tap into reserves of strength to push beyond that. Then there's also the question of what realms of influence you have. If you are in the position to become someone who works in politics, and you want to work at preventing a global conflict that way, I think that is a really good way to go.

But there is also quite a large international anti-war and peace-building community that you can tap into. There are people at the international level, and also in certain regions, trying to create a robust network at multiple different levels, in different sectors. How can we bring together people who work in the intelligence community, in the military, in NGOs, or as religious leaders? What basis do they have to work together? I think for most people that the only avenue is through horizontal connections.

Of course, there's also voting, which is important. When and where it is possible, keep issues of peace and conflict in your mind when you go to vote.

Barry: Absolutely. Clare asks, “Are you aware of any current work that's being done in the field to reduce the likelihood that malevolent actors gain positions of power in society — i.e., working upstream of the problem and just trying to prevent bad actors from getting into a position of power in the first place?”

Noah: That's an interesting question. One perspective that's quite prevalent in the community that works on peace processes is that there actually isn't such a thing as a “conflict spoiler.” It's that the people who are framed as conflict spoilers are often just unaddressed parties, or parties who are not being heard, or whose needs are not being met. I don't know if that is true in all cases, but I have found that often someone who is seen as a conflict spoiler has been excluded from a peace process.

But [we can also] look at the realm of corruption and criminality in issues of peace and conflict. Then you do have this issue of people who may be [inserting] themselves into an ongoing peace process just to cause harm, because it ensures that they continue to sell weapons or drugs. This becomes quite an important issue that is currently [addressed] in the realm of anti-corruption, and not usually adequately addressed in the field of peace and conflict studies.

It would be interesting to make that question more future-oriented: How do we take what has been learned in the past on this particular issue? Then we might extrapolate that out into a set of guiding ideas for peace work in the future. That would be a very important question.

Barry: Thank you. This is a quite a topical question: Do you think whichever country is the first to get a credible vaccination for COVID-19 will become the most powerful nation in the world? How do you see the geopolitics playing out with vaccinations?

Noah: I think that certainly whichever country, if it is a country, gets this vaccine will wield a tremendous amount of power at the geopolitical level, [not to mention] a huge amount of financial power. That is something we've seen; you can look at history and how pandemics have shaped and reshaped national power structures, as well as international power structures.

I would venture to say that whether it becomes an issue of conflict or not would depend a lot on how that country decides to use it. You could imagine a country gaining the COVID vaccine and being quite generous in how they allow people to use it, in order to increase their moral standing in the geopolitical sphere, or to [accumulate] a lot of “good karma points” that they're hoping to cash in later. But if it becomes a tool of bending other countries to their will, I think that it could be a huge source of conflict.

Barry: I want to finish off with some more questions about what individuals can do. If you're an individual in China, is there anything that you could be doing to reduce or eliminate negative impacts of a great-power conflict?

Noah: I think that [given] the bit that I know about the peace studies community in China, the people in it are very motivated and really trying to expand it quite quickly. If you get in touch with me, I can put you in touch with the people who are trying to start that up. It seems, at least as an outsider, that a lot of this peace study discourse is [happening] in the universities. Those might be places where there is a space for that dialogue.

But the question I would then have is: Where could you go from there? How could it be extrapolated to different kinds of community work? I don't really know what the space for community work is in China. But you could also look at virtual options, and consider how we could build a US-China, multi-track, grassroots peace-building network. That could also be quite important for creating a robust system to understand the incremental nature by which great-power conflicts happen. But [considering] how we might be able to intervene [is important], as [the risk of such conflict] is increasing.

Barry: Great, and I’ll finish with a final question: For people who want to explore this field more and read up on different areas, are there any particular books or articles that you would recommend, and more particular questions for people to work on?

Noah: Yes. In my view, one of the best book series for an overview of the entire field of peace and conflict studies is called the Many Peaces trilogy. It's written by the UNESCO Chair, Doctor Wolfgang Dietrich. I think it is a pretty good one-stop shop to get a sense of what the field of peace studies is, and also where you could go from there.

I think that the works of John Paul Lederach in the US also provide a really grounded and heart-oriented approach to how we understand peace work at the community level.

Barry: Brilliant, thank you.