Steven Byrnes

Bio

Hi I'm Steve Byrnes, an AGI safety researcher in Boston, MA, USA, with a particular focus on brain algorithms—see https://sjbyrnes.com/agi.html

Posts 8

Comments101

Topic contributions3

Are we talking about in the debate, or in long-form good-faith discussion?

For the latter, it’s obviously worth talking about, and I talk about it myself plenty. Holden’s post AI Could Defeat All Of Us Combined is pretty good, and the new lunar society podcast interview of Carl Shulman is extremely good on this topic (the relevant part is mostly the second episode [it was such a long interview they split it into 2 parts]).

For the former, i.e. in the context of a debate, the point is not to hash out particular details and intervention points, but rather just to argue that this is a thing worth consideration at all. And in that case, I usually say something like:

- The path we’re heading down is to eventually make AIs that are like a new intelligent species on our planet, and able to do everything that humans can do—understand what’s going on, creatively solve problems, take initiative, get stuff done, make plans, pivot when the plans fail, invent new tools to solve their problems, etc.—but with various advantages over humans like speed and the ability to copy themselves.

- Nobody currently has a great plan to figure out whether such AIs have our best interests at heart. We can ask the AI, but it will probably just say “yes”, and we won’t know if it’s lying.

- The path we’re heading down is to eventually wind up with billions or trillions of such AIs, with billions or trillions of robot bodies spread all around the world.

- It seems pretty obvious to me that by the time we get to that point—and indeed probably much much earlier—human extinction should be at least on the table as a possibility.

Oh I also just have to share this hilarious quote from Joe Carlsmith:

I remember looking at some farmland out the window of a bus, and wondering: am I supposed to think that this will all be compute clusters or something? I remember looking at a church and thinking: am I supposed to imagine robots tearing this church apart? I remember a late night at the Future of Humanity Institute office (I ended up working there in 2017-18), asking someone passing through the kitchen how to imagine the AI killing us; he turned to me, pale in the fluorescent light, and said “whirling knives.”

Thanks!

we need good clear scenarios of how exactly step by step this happens

Hmm, depending on what you mean by “this”, I think there are some tricky communication issues that come up here, see for example this Rob Miles video.

On top of that, obviously this kind of debate format is generally terrible for communicating anything of substance and nuance.

Melanie seemed either (a) uninformed of the key arguments (she just needs to listen to one of Yampolskiy's recent podcast interviews to get a good accessible summary). Or (b) refused to engage with such arguments.

Melanie is definitely aware of things like orthogonality thesis etc.—you can read her Quanta Magazine article for example. Here’s a twitter thread where I was talking with her about it.

In this post the criticizer gave the criticizee an opportunity to reply in-line in the published post—in effect, the criticizee was offered the last word. I thought that was super classy, and I’m proud to have stolen that idea on two occasions (1,2).

If anyone’s interested, the relevant part of my email was:

…

You can leave google docs margin comments if you want, and:

- If I’m just straight-up wrong about something, or putting words in your mouth, then I’ll just correct the text before publication.

- If you are leave a google docs comment that’s more like a counter-argument, and I’m not immediately convinced, I’d probably copy what you wrote into an in-text reply box—just like the gray boxes here: [link] So you get to have the last word if you want, although I might still re-reply in the comments.

- You can also / alternatively obviously leave comments on the published lesswrong post like normal.

If you would like to leave pre-publication feedback, but don’t expect to get around to it “soon” (say, the next 3 weeks), let me know and I’ll hold off publication.

(In the LW/EAF post editor, the inline reply-boxes are secretly just 1×1 tables.)

Another super classy move was I wrote a criticism post once, and the person I criticized retweeted it. (Without even dunking on it!) (The classy person here was Robin Hanson.) I’m proud to say that I’ve stolen that one too, although I guess not every time.

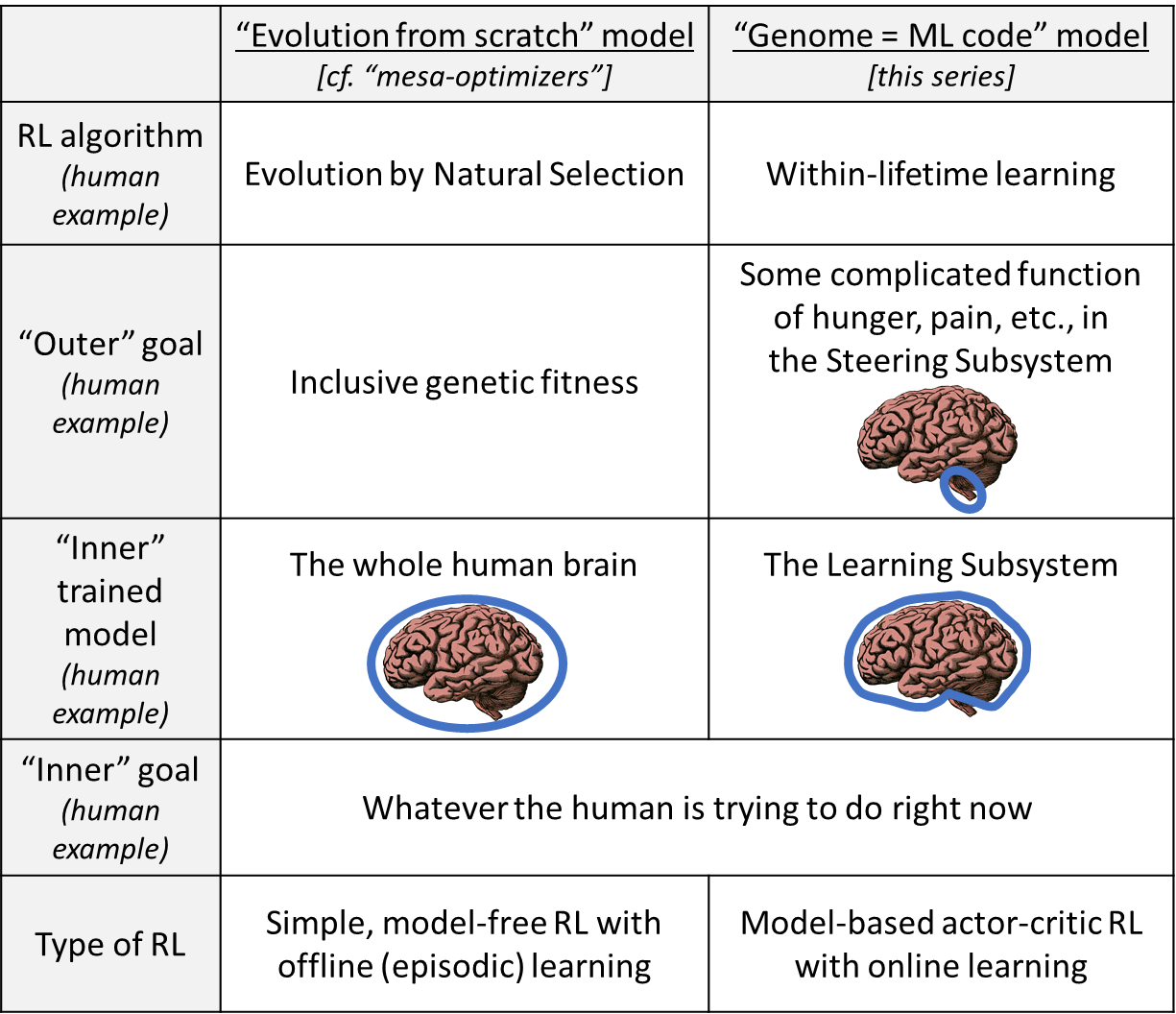

There’s probably some analogy here to ‘inner alignment’ versus ‘our alignment’ in the AI safety literature, but I find these two terms so vague, confusing, and poorly defined that I can’t see which of them corresponds to what, exactly, in my gene/brain alignment analogy; any guidance on that would be appreciated.

The following table is my attempt to clear things up. I think there are two stories we can tell.

- The left column is the Risks From Learned Optimization (2019) model. We’re drawing an analogy between the ML learning algorithm and evolution-as-a-learning-algorithm.

- The right column is a model that I prefer. We’re drawing an analogy between the ML learning algorithm and within-lifetime learning.

(↑ table is from here)

Your OP talks plenty about both evolutionary learning and within-lifetime learning, so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

However, gene/brain alignment requires a staggering amount of trial-and-error experimentation – and there are no shortcuts to getting adaptive reward functions … This lesson should make us very cautious about the prospects for AI alignment with humans.

Hmm, from my perspective, this observation doesn’t really provide any evidence either way. Evolution solves every problem via a staggering amount of trial-and-error experimentation! Whether the problem would be straightforward for a human engineer, or extraordinarily hard for a human engineer, it doesn’t matter, evolution is definitely going to solve it via a staggering amount of trial-and-error experimentation either way!

If you’re making the weaker claim that there may be no shortcuts to getting adaptive reward functions, then I agree. I think it’s an open question.

I personally am spending most of my days on the project of trying to figure out reward circuitry that would lead to aligned AI, and I think I’m gradually making research progress, but I am very open-minded to the possibility that there just isn’t any good solution to be found.

These motivational conflicts aren’t typically resolved by some ‘master utility function’ that weighs up all relevant inputs, but simply by the relative strengths of different behavioral priorities (e.g. hunger vs. fear).

I’m not sure what distinction you’re trying to draw in this sentence. If I’m deciding whether to watch TV versus go to the gym, it’s a decision that impacts lots of things—hunger, thirst, body temperature, energy reserves, social interactions, etc. But at the end of the day, I’m going to do one thing or the other. Therefore there has to be some “all things considered” final common pathway for a possible-course-of-action being worth doing or not worth doing, right? I don’t endorse the term “utility function” for that pathway, for various reasons, but whatever we call it, it does need to “weigh up all relevant inputs” in a certain sense, right? (I usually just call it “reward”, although that term needs a whole bunch of elaboration & caveats too.)

These Blank Slate models tend to posit a kind of neo-Behaviorist view of learning, in which a few crude, simple reward functions guide the acquisition of all cognitive, emotional, and motivational content in the human mind.

I’m not sure exactly who you’re referring to, but insofar as some shard theory discussions are downstream of my blog posts, I would like to state for the record that I don’t think the human “reward function” (or “reward circuitry” or whatever we call it) is “a few” or “crude” and I’m quite sure that I’ve never described it that way. I think the reward circuitry is quite complicated.

More specifically, I wrote here: “…To be sure, that’s an incomplete accounting of the functions of one little cell group among many dozens (or even hundreds?) in the hypothalamus. So yes, these things are complicated! But they’re not hopelessly complicated. Keep in mind, after all, the entire brain and body needs to get built by a mere 25,000 genes. My current low-confidence feeling is that reasonably-comprehensive pseudocode for the human hypothalamus would be maybe a few thousand lines long. Certainly not millions.”

You might also be interested in this discussion, where I was taking “your side” of a debate on how complicated the reward circuitry is. We specifically discussed habitat-related evolutionary aesthetics in humans, and I was on the “yes it is a real thing that evolved and is in the genome” side of the debate, and the person I was arguing against (Jacob Cannell) was on the “no it isn’t” side of the debate.

You might also be interested in my post Heritability, Behaviorism, and Within-Lifetime RL if you haven’t already seen it.

It’s tempting to think of the human brain as one general-purpose cognitive organ, but evolutionary psychologists have found it much more fruitful to analyze brains as collections of distinct ‘psychological adaptations’ that serve different functions. Many of these psychological adaptations take the form of evolved motivations, emotions, preferences, values, adaptive biases, and fast-and-frugal heuristics, rather than general-purpose learning mechanisms or information-processing systems.

I think “the human brain as one general-purpose cognitive organ” is a crazy thing to believe, and if anyone actually believes that I join you in disagreeing. For example, part of the medulla regulates your heart rate, and that’s the only thing it does, and the only thing it can do, and it would be crazy to describe that as a “general-purpose cognitive” capability.

That said, I imagine that there are at least a few things that you would classify as “psychological adaptations” whereas I would want to explain them in other ways, e.g. if humans all have pretty similar within-lifetime learning algorithms, with pretty similar reward circuitry, and they all grow up in pretty similar environments (in certain respects), then maybe they’re going to wind up learning similar things (in some cases), and those things can even wind up reliably in the same part of the cortex.

What counts as success or failure? You have no idea. You have to make guesses about what counts as ‘reward’ or ‘punishment’, by wiring up your perceptual systems in a way that assigns a valence (positive or negative) to each situation that seems like it might be important to survival or reproduction.

It’s probably worth noting that I agree with this paragraph but in my mind it would be referring to the “perceptual systems” of the hypothalamus & brainstem, not the thalamocortical ones. For visual, that would be mainly the superior colliculus / optic tectum. For example, the mouse superior colliculus innately detects expanding dark blobs in the upper FOV (which triggers on incoming-birds-of-prey) and triggers a scamper-away reflex (along with presumably negative valence), and I think the human superior colliculus has analogous heuristic detectors tuned to scuttling spiders & slithering snakes & human faces and a number of other things like that. And I think the information content / recipes necessary to detect those things is coming straight from the genome. (The literature on all these things is a bit of a mess in some cases, but I’m happy to discuss why I believe that in more detail.)

Your question is using "flops" to mean FLOP/s in some places and FLOP in other places.

Hmm. Touché. I guess another thing on my mind is the mood of the hype-conveyer. My stereotypical mental image of “hype” involves Person X being positive & excited about the product they’re hyping, whereas the imminent-doom-ers that I’ve talked to seem to have a variety of moods including distraught, pissed, etc. (Maybe some are secretly excited too? I dunno; I’m not very involved in that community.)

You’re entitled to disagree with short-timelines people (and I do too) but I don’t like the use of the word “hype” here (and “purely hype” is even worse); it seems inaccurate, and kinda an accusation of bad faith. “Hype” typically means Person X is promoting a product, that they benefit from the success of that product, and that they are probably exaggerating the impressiveness of that product in bad faith (or at least, with a self-serving bias). None of those applies to Greg here, AFAICT. Instead, you can just say “he’s wrong” etc.

I’m in no position to judge how you should spend your time all things considered, but for what it’s worth, I think your blog posts on AI safety have been very clear and thoughtful, and I frequently recommend them to people (example). For example, I’ve started using the phrase “The King Lear Problem” from time to time (example).

Anyway, good luck! And let me know if there’s anything I can do to help you. 🙂

I have some interest in cluster B personality disorders, on the theory that something(s) in human brains makes people tend to be nice to their friends and family, and whatever that thing is, it would be nice to understand it better because maybe we can put something like it into future AIs, assuming those future AIs have a sufficiently similar high-level architecture to the human brain, which I think is plausible.

And whatever that thing is, it evidently isn’t working in the normal way in cluster B personality disorder people, so maybe better understanding the brain mechanisms behind cluster B personality disorders would get a “foot in the door” in understanding that thing.

Sigh. This comment won’t be very helpful. Here’s where I’m coming from. I have particular beliefs about how social instincts need to work (short version), beliefs which I think we mostly don’t share—so an “explanation” that would satisfy you would probably bounce off me and vice-versa. (I’m happy to work on reconciling if you think it’s a good use of your time.) If it helps, I continue to be pretty happy about the ASPD theory I suggested here, with the caveat that I now think that it’s only an explanation of a subset of ASPD cases. I’m pretty confused on borderline, and I’m at a total loss on narcissism. There’s obviously loads of literature on borderline & narcissism, and I can’t tell you concretely any new studies or analysis that I wish existed but don’t yet. But anyway, if you’re aware of gaps in the literature on cluster B stuff, I’m generally happy for them to be filled. And I think there’s a particular shortage of “grand theorizing” on what’s going on mechanistically in narcissism (or at least, I’ve been unable to find any in my brief search). (In general, I find that “grand theorizing” is almost always helpfully thought-provoking, even if it’s often wrong.)