Epistemic status: this is a write-up of some ideas I was exploring, mostly 10-20 months ago (with many helpful comments from others). I don't think I've nailed what's going on here, but I think there are some important ideas (that I find myself wanting to refer to elsewhere!) that are probably in the vicinity of correct, and that I won't produce an excellent version in the near future, so it seems better to share the imperfect version for now. This is not really actionable advice (though some could perhaps be derived from things I have written here); I more hope that it might be of interest to people trying to think through which actions end up helping and how.

I started with a question: what are some robustly good strategies for longtermist action that assumes some embedding in a society not totally dissimilar from our own but doesn't index on being in a particular situation at a particular time? I was looking for something that's more specific than "maximise expected value" but more general than "work on AI safety". (I'd now say that I wanted a blueprint for longtermist action that would look good under the timeless (longtermist) lens.)

Statement of assumptions and main thesis

In this section I will lay out a number of assumptions, each of which seems at least fairly plausible to me, and give the statement of the thesis I reach as a result. (I am certainly making a number of other assumptions implicitly; some of them will be trivial but if there are any which are controversial I would love to know about them.) Generally I am using a consequentialist lens on what is good. I think the answer I reach make sense under various non-consequentialist lenses, but that is not my focus.

Longtermism assumption: the preponderance of what matters (in expectation) about our actions is the impact on the long-term future.

This is just assuming longtermism. I don't think one needs to fully believe this assumption to be interested in the conclusions one reaches if it is assumed.

Cluefulness assumption: Making precise predictions about the impacts of our actions is nigh-impossible; nonetheless we can make reasonable guesses about broad directional effects from some of our actions, and most of our predictable impact lies via these long-term effects.

This assumption rejects cluelessness, but grants something of the intuition which supports cluelessness (most of the time, at best we have a clue rather than really knowing what we’re doing).

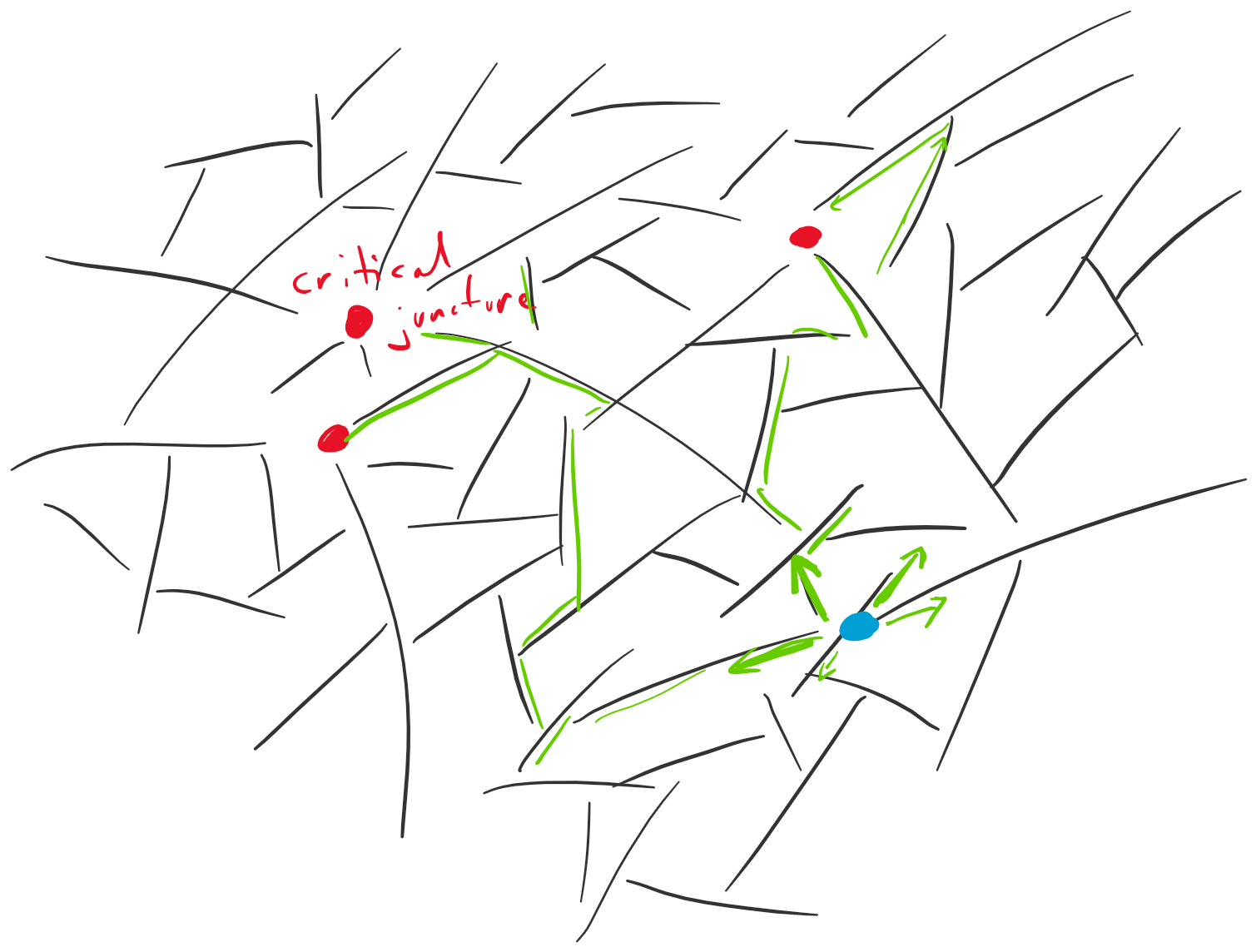

Hinge assumption: there are sometimes "critical junctures" (or "key moments" or "hinges"), scenarios which could plausibly turn out in more than one way, and whose outcome affects the trajectory of the future. Most of our expected impact factors through the outcome of such key moments.

That there could exist such moments seems like a relatively weak claim. For example this could be a moment where we go extinct or don’t as a result of developing a new technology, or the moment of writing a constitution that governs our descendants as they spread through the stars. That most of our expected impact factors through them looks like a much stronger assumption, but if one is sceptical one can simply broaden the set of junctures which count as "critical" until it seems true. (This might undermine the corollary that critical junctures are inaccessible for most people, but it won't much change the bottom line.)

From the hinge assumption, it's good to make critical junctures turn out well. However, from the cluefulness assumption, it's typically not possible to identify exactly where and when critical junctures will occur, or to predict exactly what needs to happen or how things will play out. However, I think we can be more optimistic when the actors are, for example, more wise and less corrupt than less wise and more corrupt. The “actors” involved could include both individuals and institutions. For instance this could be the engineers building a crucial new technology, or could be the UN Security Council. And we can look at a broader set of desirable characteristics (“virtues”) than just wisdom and lack of corruption.

Key virtue assumption: given the degree of our ignorance, the best accessible predictor of whether critical junctures will turn out well is how much the actors involved embody certain virtues.

Note that this is using "virtues" in a fairly broad and old-fashioned sense of "good properties", rather than necessarily the type of thing considered in virtue ethics (although I think that's an important subclass).

We can think about both which virtues of individuals matter, and which virtues of institutions matter. Exactly which virtues are key is a further important question, discussion of which I leave until a later section. Even without getting into that discussion, however, this is a substantive assumption: there could conceivably be better predictors which are not naturally understood as virtues. I make the assumption because I haven't been able to think of anything better (while giving the question some attention for years), and I want to see where it gets us, and then likely act on it until and unless we have candidates for better predictors.

Exploring the consequences of the key virtue assumption, the most straightforward case is when you are (or suspect you might be) an actor in a critical juncture. Then the guidance would be to exhibit the key virtues (which might well in turn lead to doing other things particular to the situation).

But, in my mainline understanding of the world, almost everyone is not in a critical juncture most of the time, and most people never are. In this case it seems valuable to facilitate the uptake of key virtues in actors who might be in critical junctures (adding a level of indirection). Or to help others (who also won’t be in critical junctures) to facilitate such uptake (adding a second level of indirection), or to help others help others to facilitate it, and so on …

The final assumption I'm naming is about the pragmatics of how to facilitate the spread of virtues. It's based on the observation that people tend to dislike and distrust hypocrites.

No hypocrisy assumption: if you want others to adopt virtues, it's a good idea to demonstrate them yourself.

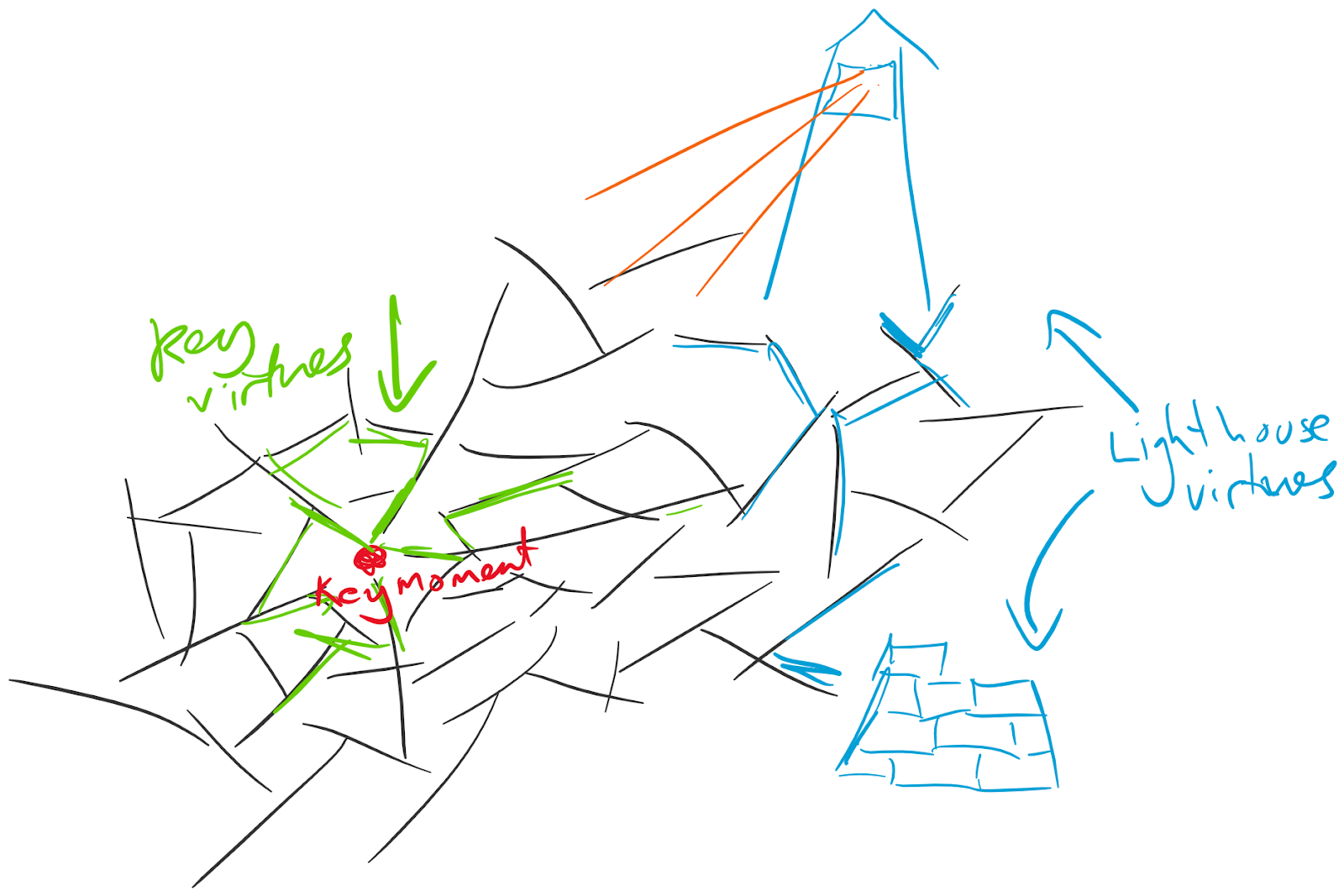

This means that the key virtues are important to convey to intermediate- as well as end-users, and by backwards induction important to embody if one wants to spread them. The picture that is emerging is of a virtuous web, with many connections between people (and institutions), and the web reinforcing itself along those connections. The web has an unknown number of centres, one for each critical juncture, in unknown locations (but we have some hints about location).

The payloads of the web of virtue are the key virtues in proximity to critical junctures. From the no hypocrisy assumption the key virtues also help the self-reinforcing nature of the web. But there may be other properties which are quite helpful for the self-reinforcement – for example, a desire to spread the key virtues and reinforce the web. Let us call those properties "web virtues".

Now we are in a position to draw together the strands and state our main thesis:

Web of virtue thesis: a good general longtermist strategy is for most people (and appropriate institutions) to cultivate key virtues and web virtues in themselves and others, skewing somewhat towards those others likely to be closer to critical junctures.

There's an inaccuracy in this picture according to whether time is supposed to be depicted on the graph (in which case properly the entire graph should be a DAG) or not supposed to (in which case red points can't really represent critical junctures, but just places in society where critical junctures might arise); it feels like a helpful picture to consider anyway.

This leaves a lot of details as open questions. As well as the question of which are the key virtues, we'd like to know which are the web virtues, and which parts of society are likely to be closer to critical junctures. In the next couple of sections I'll outline my initial thinking on each of these, although it's all extremely tentative. After that I'll talk about an extension of the model.

What are the important virtues? Where do they matter?

I think it's important to turn a critical eye on proposed lists of key virtues and web virtues. Anything that gets lauded as a virtue to be promoted could be spread in a self-reinforcing manner, so it's worthwhile being careful before setting such a process going.

Which are the key virtues

First I'll attempt a first-principles analysis. Reversing the question: the absence of which virtues could cause serious problems in critical junctures?

If we got a bad long-term outcome from some key moment, then either (1) the actors involved didn't know that this would happen; or (2) they didn't care (relative to other things affecting their actions); or (3) they knew and cared but weren't competent enough to prevent it. Subdividing (1), we have (1a) nobody knew, and (1b) someone knew, but not all of the key actors did. Subdividing (2), we have (2a) they cared little about the outcome, and (2b) they cared a lot about other things. We can analyse each of these in turn.

The risk of failure mode (1a) is reduced by "farsightedness": a propensity to understand the consequences of things. This can be improved by personal epistemic virtues (giving more accurate beliefs when consequences are considered) as well as by personal or institutional virtue which encourages the correct amount of consideration of consequences. This failure mode is unusual in that it can also be mitigated by people far removed from the key moment, by creating knowledge about what kinds of event/action could lead to bad long-term outcomes. Such people have a disadvantage in knowing fewer details of the situation, but it can be much easier to get their attention and more efficient to have them do significant parts of the analysis.

The risk of failure mode (1b) is reduced by good information flow, getting everyone to both hear and understand the relevant knowledge. This can be facilitated by: (i) those who have the relevant knowledge putting effort into disseminating it, and knowing how to do that in a way that it will be understood; (ii) individual virtues of curiosity, harmonising (seeking to integrate different perspectives rather than decide which is correct), and epistemic humility (being very conscious of all the things one doesn’t understand); (iii) institutional virtues which encourage discordant voices to speak up (e.g. whistleblower protection) and seek to get to the bottom of disagreements (e.g. independent review).

The risk of failure mode (2a) is reduced by (individual and institutional) buy-in to "longtermism", as well more broadly as the virtues of altruism and scope sensitivity.

Some of the risk of failure mode (2b) is mitigated by personal integrity, and by institutional structures which reduce conflict of interest. I am worried that a particularly perfidious driver of (2b) is power struggles, as well as perceptions of risk of power struggles. This can be reduced by the personal (and institutional) virtue of cooperativeness, as well as the institutional (and personal) virtue of legibility.

Failure mode (3) is reduced by normal competence-increasing measures, including putting more competent actors into positions of power. In cases where competence involves solving technical problems, it may be possible for some or all of the work towards a solution to take place elsewhere (perhaps by people far removed from the key moment).

Stepping back from this analysis, I think that a general characterisation is something like "things that tend to make decisions go well". While we perhaps care just about particular classes of decision, there might be some very useful empirical work to look into what is known about what tends to lead to good versus bad decisions made by groups/institutions/individuals.

Which are the web virtues?

You can cultivate virtues close to places that matter either by changing which actors are in the positions that matter, or by fostering virtues within those actors.

I suspect that web virtues will vary quite a bit with:

- Whether one is aiming to change who has power, or to improve those in power;

- Whether you are an individual or an institution;

- Whether you are trying to cultivate virtues in individuals or institutions.

For example institutions trying to cultivate virtues in individuals might often do this by trying to develop mechanisms to reward good behaviour or discourage bad behaviour (or to set up structures to support institutional culture doing this). Individuals trying to change which other individuals have power might do this in political campaigns, or when making hiring decisions. Individuals trying to improve existing institutions might do this by providing accountability for good and bad aspects of the present institution, and providing their findings to stakeholders that the institution is accountable to.

In general as an individual I guess that it's good to be: actively transparent about what one values (ideally calling out and rewarding virtues in others); respectful and considerate of others even when one disagrees, but firm about important disagreements; willing to hold power (and be seen to use it responsibly) but not desperately seeking it.

I think this section could productively use quite a lot more analysis.

Where in society should the web be oriented?

I guess that critical junctures are most likely to arise with the development or deployment of powerful new technologies; perhaps also in other moments of crisis or power struggle. Actors who might have direct influence over these things are therefore of particularly high priority.

Then more broadly actors who might have cultural influence over such actors look somewhat important. This could include:

- the industries the disruptive technology might arise from

- politicians; the civil service

Stepping back, we might look at actors who may be in a position to have broad cultural influence:

- the media; storytellers

- academics; other researchers publishing publicly

- the rich and/or famous

- educators

Then other actors who are closer to having influence with one or more of these groups (but at some scale it gets very broad; e.g. anyone involved in raising a child is in some sense an educator).

Lighthouses

In analysing key virtues, I noted a couple of places where useful work could be done by people far from the critical junctures. This was work which casts light on how things may turn out, and what is good to do. In our metaphor we might consider this work as building lighthouses which are available to help navigation by those in critical junctures.

With this enriched picture, it is desirable for us to have lots of key virtues around the critical junctures, and also desirable to have excellent lighthouses (which are both trustworthy and trusted). So we would like the web of society to both cultivate the accumulation of key virtues near critical junctures, and the construction of excellent lighthouses. This adds a second set of payloads for the web of virtue to carry: we could call the virtues that lead to the construction of excellent lighthouses "lighthouse virtues".

People in key moments may put differing amounts of effort into looking for and vetting lighthouses, so excellence in a lighthouse depends on addressing important junctures (stretching the metaphor, perhaps this is shining in the right direction), being easy to find and perceived as worth listening to (having a tall tower), and actually having useful insight to contribute (shining clearly).

I guess that the lighthouse virtues will have significant overlap with the key virtues, particularly the epistemic elements. For lighthouse-building, perceiving anything real from the fog of the future, and staying oriented to what most matters, is likely even more important. Virtues of clarity of communication, and distilling knowledge, are more centrally important for building lighthouses. On the other hand personal integrity and cooperativeness are of more central importance for actors in key moments (though lighthouse-builders are also likely to play a significant role in the web of virtue, so I think these still matter above and beyond the commonsense reasons that it is good for the industry).

Hi Owen, I think this paper (and the other stuff you have posed recently) are very good. It is good to see breakdowns of longtermism that are more practicably applicable to life and to solving some of the problems in the world today.

I would like to draw your attention to the COM-B (Capability Opportunity Motivation - Behaviour) model of behaviour change in case you are not already aware of it. The model is, as I understand it a fairly standard practice in governance reform in international development. The model is as follows:

I think it is useful for you to be aware of this (if you are not already) as:

I hope this is useful for resolving some of the uncertainty you expressed about the Key Virtue assumption and for refining next steps when you come to work on that.

I would caveat that I find COM-B useful to think through but I am not a practitioner (I'm like an EA thinking in QALYs but not having to actually work with them).

I think there is a meta point here that I keep reading papers from FHI/GPI and getting the impression (rightly or wrongly) that stuff that is basic from a policy perspective is being being derived from scratch, often worse than the original. I would be keen to see FHI/GPI engage more with existing best practice at driving change.