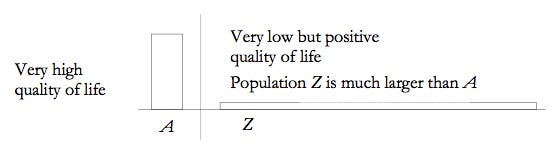

I recently published two articles on population ethics entitled “In Favor of Underpopulation Worries” and “Scott Alexander, Population Ethics, and Playing the Philosophy Game,” as well as a defense of preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disorders (PGT-P) entitled “Harmless Eugenics.” While these topics might seem relatively unrelated, views about population ethics are very relevant to the ethicality of genetic enhancement. This connection may go unrecognized because discussions of population ethics are often focused on avoiding implications like the Repugnant Conclusion, which is the idea that “[f]or any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living” (Parfit, 1984).

My population articles addressed some arguments about creating people made by psychiatrist and rationalist blogger Scott Alexander. Contra Alexander, I believe that underpopulation is bad from a consequentialist perspective because the existence of happy people is morally good. While I acknowledged Alexander made a somewhat persuasive case as to why a less-than-maximally-populated world would be okay, I also believe that having fewer people around means fewer people experiencing the joys of life. I argued that utilitarians should embrace the total view—the idea that “[o]ne outcome is better than another if and only if it contains greater total wellbeing” (Chappell et al., 2022). And so they should accept the Repugnant Conclusion.

Alexander later rather reluctantly endorsed the population ethic that “it’s always bad to create new people whose lives are below zero, and neutral to slightly bad to create new people whose lives are positive but below average.” He also expressed some reservations about even engaging in this sort of thinking, saying he is unsure as to whether he wants “to play the philosophy game.” I critiqued this odd stance on philosophy and pointed out all the wild implications of Alexander’s unusual population ethic in “Scott Alexander, Population Ethics, and Playing the Philosophy Game.”

In an even later article “Highlights From The Comments On The Repugnant Conclusion And WWOTF,” Alexander mentioned a comment pointing out that his view had issues, one being that it resulted in the Sadistic Conclusion—"it is better, for high-average-welfare populations, to add a small number of people with negative welfare than a larger number with low-but-positive welfare, for sufficient values of 'larger'.” Alexander responded to this comment by saying:

Thanks, I had forgotten about that.

I think I am going to go with “morality prohibits bringing below-zero-happiness people into existence, and says nothing at all about bringing new above-zero-happiness people into existence, we’ll make decisions about those based on how we’re feeling that day and how likely it is to lead to some terrible result down the line.”

I suppose I commend the uncertainty with which he embraces this position. One point I made in my second response article is that Alexander should either accept the Repugnant Conclusion or more fully embrace intuitionism and reject consequentialism. In the highlights article, Alexander does identify as an intuitionist. It seems that he might be an intuitionist with regard to population ethics but largely consequentialist with regard to other moral dilemmas. I’m rather unsure at this point.

I’m not sure how moral realist vs. anti-realist I am. The best I can do is say I’m some kind of intuitionist. I have some moral intuitions. Maybe some of them are contradictory. Maybe I will abandon some of them when I think about them more clearly. When we do moral philosophy, we’re examining our intuitions to see which ones survive vs. dissolve under logical argument.

The repugnant conclusion tries to collide two intuitions: first, that the series of steps that gets you there are all valid, and second that the conclusion is bad. If you feel the first intuition very strongly and the second one weakly, then you “have discovered” that the repugnant conclusion is actually okay and you really should be creating lots of mildly happy people. I have the opposite intuitions: I’m less sure about the series of steps than I am that I’m definitely unhappy with the conclusion, and I will reject whatever I need to reject to avoid ending up there.

Unfortunately, rejecting the Repugnant Conclusion leads to more counter-intuitive outcomes when compared to the alternatives. Also, it’s worth noting that it isn’t clear that human welfare is reduced by additional people at current population levels. I would argue net human welfare is increased even if we exclude the individual person’s welfare. People participate in the economy, have friendships, and bring joy to their families in most cases. However, it may very well be the case that humans are net negatives to the world because of animal suffering in factory farms. For now, I am going to assume that is not the case, although the belief is not unreasonable at all.

We could also perhaps reject some of the possible implications of the Repugnant Conclusion if we accept natural rights and reject the utilitarian view that “we ought to maximize welfare.” If we accept some deontological concerns, we could constrain ourselves by not violating anyone’s natural rights to increase the population. We could also reject the demandingness of utilitarianism and say that while having twenty children might be morally virtuous, you have no obligation to do it. The Repugnant Conclusion paired with a demanding utilitarian ethic is especially difficult to accept.

Yet again, the RC seems easier to accept than Scott Alexander’s proposed solution. The aspect of Alexander’s new population ethic, which “says nothing at all about bringing new above-zero-happiness people into existence”—a viewpoint called procreative asymmetry—has its own problems. For one, you cannot make a judgment about creating the populations involved in the Repugnant Conclusion. You necessarily must be indifferent between the small population A and the large population Z. While this is likely not as bad as having to choose population Z for Alexander, this hardly seems satisfactory if someone rejects the repugnant conclusion.

A more absurd implication is that we would be extremely intolerant of small amounts of negative lives even if they came with a tremendous number of extremely happy lives. The extremely happy lives are worth nothing, but the negative lives are worth a negative value. Imagine in the graphic above that there are 10 billion people in A with high welfare and one single person that doesn’t appear because he is less than a single pixel. Let this single person have ever-so-slightly negative welfare. In this case, you basically have the Repugnant Conclusion again. Another strange implication is that we would prefer a world with nobody rather than billions of happy people and a few who are unhappy.

The indifference between positive welfare levels is particularly odd. When thinking abstractly, perhaps some could tolerate this idea. However, the practical implications seem particularly distasteful.

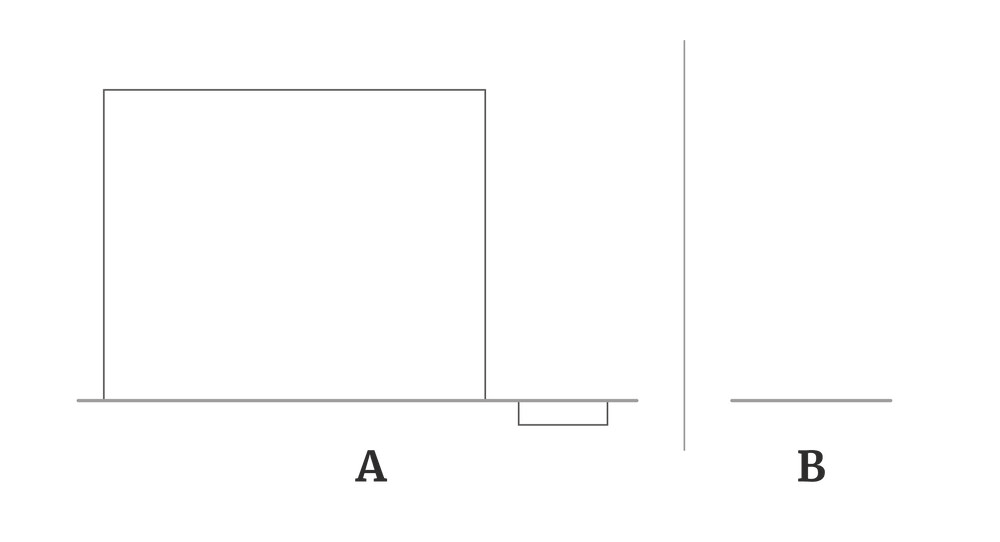

Recall the process for polygenic genetic testing for polygenic disorders (PGT-P). When a couple is conceiving using in vitro fertilization, eggs are extracted and fertilized in a laboratory rather than inside of the mother. After the zygotes mature into embryos, biopsies can be performed to evaluate the future health of the embryo. With PGT-P, the embryo’s DNA is used to determine polygenic risk scores (PRS) for various disorders. Embryos can then be selected to avoid these disorders. At the company Genomic Prediction, these scores are aggregated into a unidimensional Embryo Health Score (EHS), which is “the sum of the predicted absolute risks for each disease condition weighted by the life-span impact of the condition” (Tellier et al., 2021).

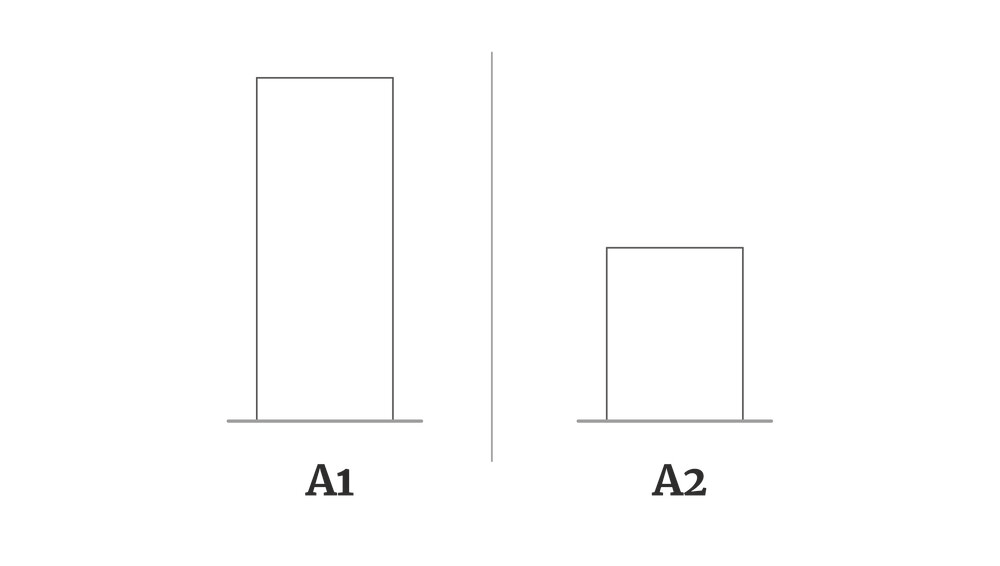

Imagine that a couple agreed to go through all the trouble of attaining the Embryo Health Score for a large group of embryos, but instead of selecting the healthiest embryo, they selected the embryo they expect to live the worst life worth living. Does this seem morally acceptable? Consider two worlds with widespread embryo selection. In world A1, all parents pick the child with the highest EHS. In world A2, all parents pick the child with the lowest EHS, provided the child’s life is still worth living.

If we truly have an ethic that “says nothing at all about bringing new above-zero-happiness people into existence,” we cannot cast moral judgment on the parents who bring the least healthy embryos into existence. However, it seems obvious that parents have some moral motivation to actually pick the healthiest embryo rather than the most sickly, even if parents have a strong desire to have a sickly child. This sort of desire should carry approximately zero weight in moral decision-making.

A person might be tempted to say that selection is different from creation because it harms the child by giving it unwanted diseases. I do not think this objection works. The child wouldn’t exist had another embryo been selected. The counterfactual world is one in which the child does not exist, rather than one in which the child is healthy. It does not matter whether we regard an embryo as a person or not. Had the parents not intentionally undergone the embryo selection process, the resulting child would not have been any of the embryos created in the lab. This rests on the assumption that souls are not waiting in a sort of queue for couples and that conscious experiences would be had by the same person.

Although the person is not harmed by selecting the embryo with the lowest EHS, it still seems wrong. My intuitions make me rather sympathetic to Julian Savulescu’s principle of Procreative Beneficence, which states that “couples (or single reproducers) should select the child, of the possible children they could have, who is expected to have the best life, or at least as good a life as the others, based on the relevant, available information.” (Savulescu, 2001). In his article “Procreative beneficence: why we should select the best children,” Savulescu provides intuitions as to why we might support this principle.

The following example, after Parfit,1 supports Procreative Beneficence. A woman has rubella. If she conceives now, she will have a blind and deaf child. If she waits three months, she will conceive another different but healthy child. She should choose to wait until her rubella is passed.

Or consider the Nuclear Accident. A poor country does not have enough power to provide power to its citizens during an extremely cold winter. The government decides to open an old and unsafe nuclear reactor. Ample light and heating are then available. Citizens stay up later, and enjoy their lives much more. Several months later, the nuclear reactor melts down and large amounts of radiation are released into the environment. The only effect is that a large number of children are subsequently born with predispositions to early childhood malignancy.

The supply of heating and light has changed the lifestyle of this population. As a result of this change in lifestyle, people have conceived children at different times than they would have if there had been no heat or light, and their parents went to bed earlier. Thus, the children born after the nuclear accident would not have existed if the government had not switched to nuclear power. They have not been harmed by the switch to nuclear power and the subsequent accident (unless their lives are so bad they are worse than death). If we object to the Nuclear Accident (which most of us would), then we must appeal to some form of harmless wrong-doing. That is, we must claim that a wrong was done, but no one was harmed. We must appeal to something like the Principle of Procreative Beneficence.

It seems clear that the woman with rubella should wait and that it was likely wrong to open the nuclear reactor even if no one was harmed. These scenarios are very unrelated to the type of thinking involved in abstract population ethics. When solely focusing on avoiding unwanted conclusions in population ethics, one might neglect to consider the practical implications in the real world. A theory with an indifference to the creation of happy people seems to have a major blindspot.

Perhaps this was less relevant centuries ago when parents had little understanding of genetics, and there were no technological means to genetically enhance. The ethics of creating people are more salient now. Should parents, lawmakers, and doctors be guided more by Savulescu’s Principle of Procreative beneficence, or more according to procreative altruism “according to which parents have significant moral reason to select a child whose existence can be expected to contribute more to (or detract less from) the well-being of others than any alternative child they could have” (Douglas et al., 2013)? How many IQ points should parents sacrifice for an additional year of life? How tall is it morally acceptable to create your male offspring? Should parents have full reproductive autonomy, or should regulators have some say? These questions will become increasingly relevant in the coming decades, and it is incredibly important that we advocate for creating healthy, happy, and moral people. We cannot be indifferent to the quality of happy potential people’s lives.

1 D. Parfit. 1976. Rights, Interests and Possible People, in Moral Problems in Medicine, S. Gorovitz, et al, eds. Englewood Cliffs. Prentice Hall. D. Parfit. 1984. Reasons and Persons. Oxford. Clarendon Press: Part IV.

This is a minor point but I wish people would stop trying to rehabilitate the term 'eugenics' for things that are harmless/morally ok (or claimed to be). I think this just primes people to think that you are edgy and that you support the more extreme forms of this, so in general, insisting on using that term will make people less receptive to your arguments (except for alt-right people). I know that etymologically eugenics means 'good genes' and the original eugenicists weren't all Nazis. But like, a lot of them were Nazis, and even the ones that weren't, supported things that are abhorrent by our current morality. Even though the concept of changing human genetics is morally neutral, the term 'eugenics' is now just unavoidably associated in the English language with coercive and brutal ways of doing that.

Thanks for your thoughts, Amber. In this article, I just used the term "eugenics" to mention my other article "Harmless Eugenics." In that article, I do not advocate for using the term "eugenics" to describe genetic enhancement normally but I seek to find a way to deal with the accusation of being a eugenicist or advocating for eugenics. I thought it might be an effective move to ask people to find the harm involved and then provide some potential responses. From the article (bolding for emphasis):

I agree with you that it may be better for optics to not just say "I like eugenics" or something along those lines. But if you do advocate for this voluntary procedure in which a woman is exercising her reproductive autonomy, you will be accused of eugenics. The issue I wanted to address was how to deal with that. I find saying "this is not eugenics" inadequate. So, I think a good move is to make your interlocutor find the harm involved. I address a bunch of possible responses.

Note that "parity" value relations allow that one could be indifferent (or perhaps ambivalent) about adding happy lives, while still always preferring that any added life be more happy rather than less so. So one can accept conditional principles like Procreative Beneficence without any commitment to the total view (or any other population-ethical view on which it is good to create happy lives).

Thank you for commenting, Richard! Good to see you. Yes, that is a good point. I think that a move from "we can say nothing" to this attitude would be a step in the right direction. I do agree that accepting PB doesn't mean you have to accept the total view.