Political institutions, such as governments and international organizations, are instrumental in designing large-scale coordination mechanisms and collective action. However, political decision-making is difficult to both achieve and optimise for many reasons. Examples include these decisions’ collective nature, their high stakes, the complexity of policy problems, and slow feedback loops to learn from implementation. The support and improvement of political decision-making could, therefore, be highly impactful. The ultimate question is: What works?

This talk, from Max Stauffer of the Geneva Science-Policy Interface, delves into the impact, evidence, and implementability of four popular strategies to strengthen political decision-making. Max also provides recommendations for further work.

We’ve lightly edited a transcript of the talk for clarity. You can also watch it on YouTube and read it on effectivealtruism.org.

The Talk

Habiba Islam (Moderator): Hello, and welcome to this session, “How to guard the guardians themselves: Strategies to support political decision-making,” with Max Stauffer. I'm Habiba Islam and I'll be the emcee.

For this session we'll start with a 20-minute talk by Max, and then we'll move on to a live Q&A session in which he'll respond to [audience members’] questions. [...]

Now I'd like to introduce our speaker for this session. Max Stauffer is a science policy officer at the Geneva Science Policy Interface, which seeks to build bridges between scientists and the United Nations. He's also the founding co-president of EA Geneva and a founding partner at the Social Complexity Lab. Max's background is in international relations and complex systems. He's currently co-writing a book on placing longtermism at the core of policymaking. Here's Max.

Max: Hello, everyone. My name is Max Stauffer. I work for the Geneva Science Policy Interface. I'm excited to present the preliminary results of research that I'm conducting together with Konrad Seifert from Effective Altruism Geneva. Our research focuses on how to guard the guardians themselves — that is, how can we support policymakers in their decision-making?

The key points of my talk, with respect to how to improve political decision-making, are the following:

* We believe that we should focus on information processing and heuristic decision-making instead of bombarding decision makers with more information, even if that information is more accurate.

* While popular, nudges and diversity do not seem to adequately support political decision-making.

* In contrast, we found that other strategies, like multi-criteria decision analysis and “serious games,” seem much more promising to support decision-making.

What are the implications and next steps of this research? First, more careful experimentation is needed before better synthesis can be done. This is quite important. Second, we need analysis of more strategies, especially in specific contexts [involving] specific problems.

Overall, we provide a conceptual basis and methods to think about improving political decision-making and to guide further research. In this talk, I am going to explain how we arrived at those conclusions.

The context behind this research is that political institutions are essential but difficult to influence. They're essential because they enable large-scale collective action, for example [through] regulations. But the problem is that policymaking is a complex process. It features many different actors who have different interests. And it has complicated legal, technical, and social processes.

It is also highly institutionalized, in the sense that policymakers are truly experts in their domains and they know how to navigate policymaking systems [and processes]. If we want to improve policymaking, we need in-depth knowledge about those processes.

As a response to this difficulty, we've been working on a book called Long-term Political Decision-Making. It aims to provide guidance on how to understand policymaking systems and engage in them with a longtermist perspective. While this book focuses on longtermism, today I'm going to present the most cause-neutral chapter, which is about improving decision-making.

[This chapter addresses] the following questions:

* How can policy actors improve their decision-making, and what does that even mean?

* What strategies can be implemented?

* What do we know about existing strategies?

* What can we recommend based on the current state of evidence?

The way one solves this puzzle depends on how one looks at policymaking. There are [different] ways to understand it. One can look at it as:

* A black box, with a mix of social and technical inputs into policies

* A set of formal procedures which [reflect] a relationship between the legislative and executive branches of government

* A process of policy formation, from agenda-setting, to policy design, to policy implementation and evaluation, etc.

* [A matter of] dynamic trends — policymaking as [a series of] responses to changes

* A social network — policymaking as a set of individuals whose interaction leads to the emergence of policies

It is this last conceptualization that we use. Yes, it is embedded in formal procedures, and the policy cycle also generates macro trends.

But if one zooms in to this social network, one can identify policy teams — groups of individuals who need to make sense of the world and design policies. The question we're asking is: How can we support the decision-making of these policy teams?

There is actually a vast literature on decision-making support, like the provision of better evidence, better predictions, and policy-relevant publications. That has been the focus of policy and system analysis. Today, there are even systematic reviews that explain how to do this job very well. I highly recommend reading these studies.

There's another [subset] of literature that emphasizes the components of information processing, which is how people select, use, and turn information into decisions. This is highly related to the literature on rationality and heuristic decision-making, which says that humans, in the face of uncertainty (as in policy contexts), rely on decision-making heuristics based on the interplay of what happens in the brain when inputting a supply of information.

[...] The question is: What is the impact of information processing strategies in policy contexts and collective [decision-making] settings? We looked for answers in the literature and did not find reviews that compared different strategies to [ascertain] their respective impact on decision-making. As a result, we decided to conduct a review ourselves.

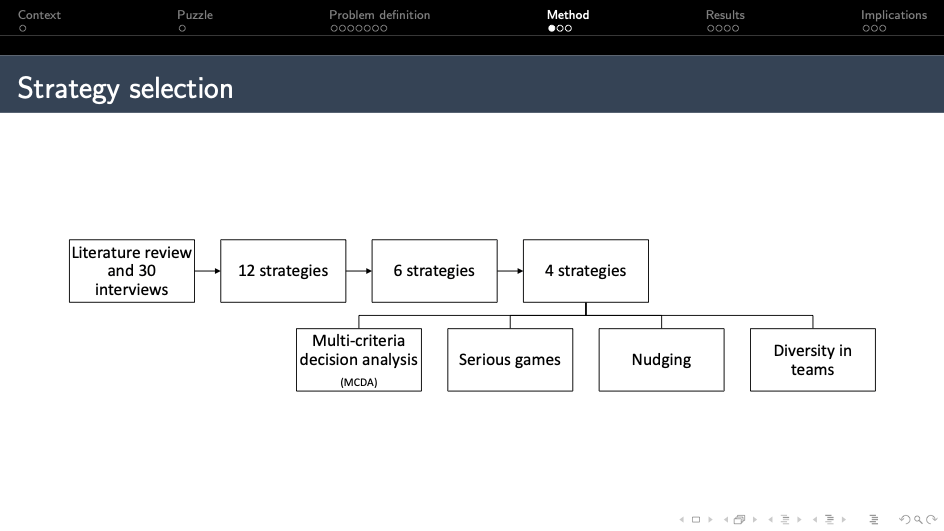

One can imagine the thousands of ways that we could improve information processing and decision-making. We conducted a literature review and 30 interviews with technical officers, diplomats, and policymakers to better understand the options they faced. We identified 12 strategies and narrowed them down to four. In the end, we analyzed the four that you see on this page:

1. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), which is essentially the formal process that guides decision makers in their prioritization;

2. Serious games, which are in-person simulations that allow decision makers to experience the outcomes of their decisions and navigate complex problems, but in a simulated setting;

3. Nudging, which consists of simple changes in the choice architecture of decision makers; and

4. Diversity in teams, which [involves] increasing different types of diversity (like background diversity, seniority diversity, or ethnic diversity) in decision-making teams.

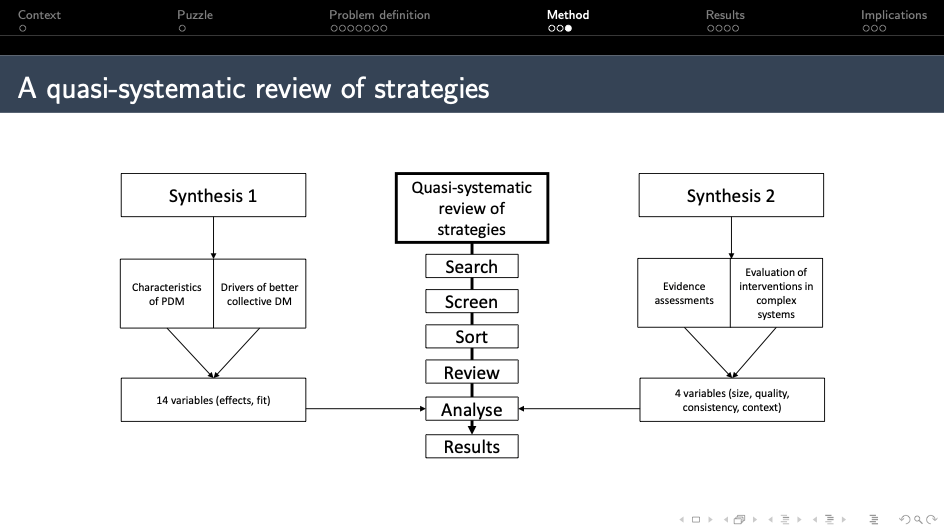

Our method is a quasi-systematic review and based upon two syntheses. On the left is Synthesis 1, for which we reviewed the characteristics of ethical decision-making and the drivers of better collective decision-making. We identified 14 variables, through effects and fit, in analyzing the impacts of strategies.

In Synthesis 2, we reviewed frameworks by evaluating the evidence [around] strategies and interventions in public systems. That [resulted in] four variables: the size, quality, consistency, and context of the evidence.

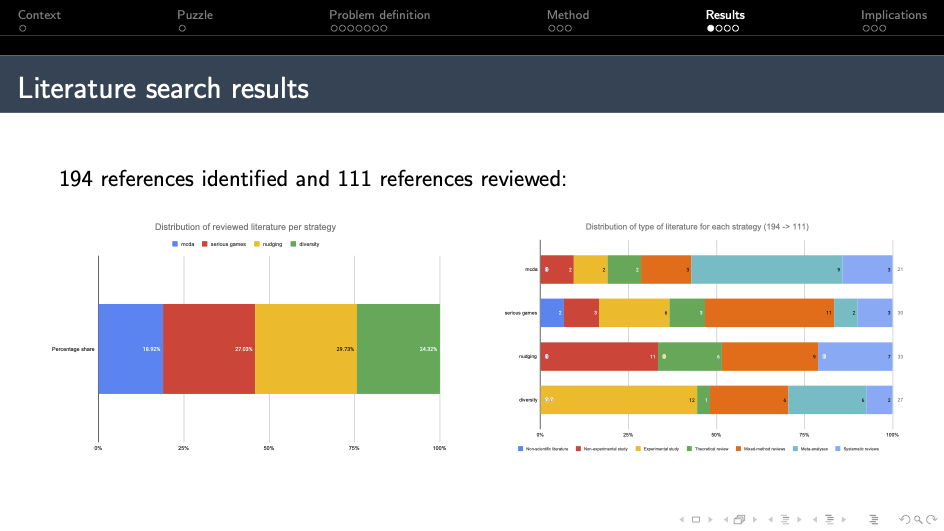

Based on these two syntheses, we could connect our quasi-systematic review strategies and analyze impact and evidence strength. We identified 194 references and reviewed 111 of them, which were more or less equally distributed across the four strategies [MCDA, serious games, nudging, and diversity].

On the right you can see the distribution of the types of literature according to each strategy. On the first line, you can see that our assessment of MCDA was heavily based on systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and other reviews, while on the last line, you can see that our analysis of diversity was mostly based on experimental studies. [This] shows that different strategies [are affected by] the different levels of maturity in their respective fields.

In terms of the results on impact and evidence strength, for impact we evaluated strategies according to two dimensions: effects and fit. For the “effects” [criterion], we evaluated the extent to which strategies contribute to several drivers of better collective decision-making: facilitation, group cohesion, intergroup competition, intragroup interaction, participative decision-making, and clear process structures.

For the “fit” [criterion], we assessed the extent to which strategies fit political complexity, including epistemic uncertainty, moral uncertainty, time constraints, slow feedback loops, etc. We scored strategies using binary scores. The literature was not precise enough [for us to complete] a more specific analysis; we could only assess whether the strategy was or wasn’t viable.

At the bottom of the table you can see that MCDA and serious games scored much better than the other two strategies. We'll talk about that in a minute.

On the right, in terms of evidence strength, you can see that each strategy scores [in the] “medium” range on evidence strength, but for different reasons. With nudging, for example, the [relative] quality of the evidence and the experimental studies was scored as high, but the literature actually shows inconsistent results and doesn't fit our political context very well.

In contrast, if you look at MCDA, you see much better consistency and contextual applicability, but the quality of the data and the experimental studies is much lower. For diversity, there is a low quality [score] and very low consistency; this is because the literature is not very clear about what diversity actually means.

In terms of context, the studies were mostly applicable to organizations and companies, but very rarely to political contexts. For serious games, context applicability is high, consistency is okay, and the data quality and experimental studies were quite weak.

[Above] are the main results of the chapter, which reflect the expected impact of the strategies, with the reported impact on the x-axis and the evidence strength on the y-axis.

You can already see two clusters. The one on the right, with MCDA and serious games, seems robust and promising for supporting decision-making. On the left, diversity and nudging seem much less promising than MCDA and serious games. This is the case because MCDA and serious games were a [strong] fit [in terms of] context; the literature is actually about political decision-making. For diversity, the literature is generally not [rooted in a] political context, and also shows inconsistent results in terms of impact. Most of the impact [pertains to] innovation, which is not the same as political history.

Nudging is very low because 100% of the literature on it does not tackle decision-making in a political context. Instead, nudging seems most beneficial for very simple decisions around password selection, food choices, and energy consumption choices, which are not [the types of] decisions you find in policymaking.

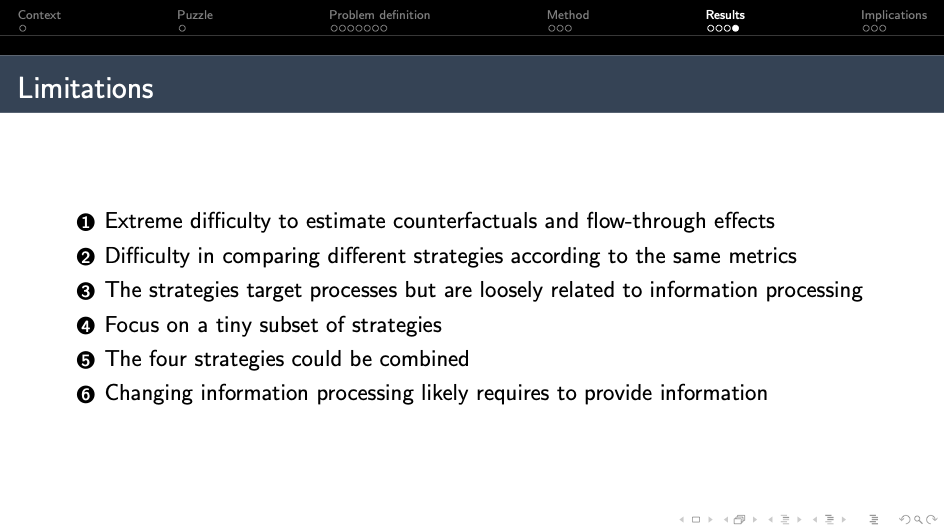

There are limitations of this research:

1. It’s extremely difficult to estimate the counterfactuals and the flow-through effects of these strategies. While we could assess the drivers of better collective decision-making, we could not assess the decisions’ impact, especially when there are ethical [issues at] stake. We don't know whether MCDA leads to helping more people to a greater extent.

2. It's difficult to compare different strategies [using] the same metrics. And since we didn't find past literature that does that, we had to pioneer a method, and a lot of improvements could be made.

3. Although the strategies target decision-making and social processes, they are only loosely related to information processing; they do not directly focus on how we perceive and use information.

4. We only focus on a subset of strategies — just four — which is a very tiny representation of the entire option space.

5. The four strategies could be combined, in the sense that MCDA, nudging, and diversity could actually be features of a serious game. But we did not account for these dependencies.

6. Ironically, changing [how people process] information likely requires providing them with information. For example, if we want policymakers to use MCDA, we would probably need to provide training on MCDA, and then test them on that information. As a result, we would not solve the puzzle of how people actually use information.

As a conclusion, how can we guard the guardians themselves?

First, we need to understand that policymaking is a very information-rich environment. Simply bombarding decision makers with more information — even if that information is required — will not necessarily lead to better decisions. Instead, we believe that we need to equip decision makers with tools to select the right information and transform it into better decisions.

Also, in our review we found that nudging and diversity, while quite popular in the literature and in practice, do not seem adequate to support political decision-making, as they do not tackle the drivers of ethical decision-making. In contrast, we found MCDA and serious games much more promising in helping policymakers arrive at the right decisions.

In terms of next steps, we need:

1. More careful experimentation with empirical evaluations of these strategies, which will lead to better synthesis. Our synthesis was mostly based on references of low to mediocre quality.

2. More analysis of more strategies so that we have a better understanding of the option space. We also need analysis of more specific contexts to understand the usefulness of certain strategies for certain problems.

3. [A continuation of our work] from other researchers. We provided a conceptual basis or method for thinking about improving political decision-making processes and to guide future research. We would be quite happy if other researchers would pick up on this and do a much better job.

We think that this research is important and feasible. Decision-making is at the core of policymaking processes, so if we do a better job of making decisions, we can strengthen [both areas], and, as a result, hopefully improve the world.

Thank you very much for your attention. I'm looking forward to the Q&A.

Habiba: Thank you for that talk, Max. I see we've had lots of questions submitted already, so let's dive in. To start, could you provide some context around the book (one chapter of which your talk focused on)? What topics do you cover and who is the audience?

Max: Sure. Thank you for having me. The book is a project that we started about 18 months ago. In EA Geneva, we were thinking about how the EA community might improve policymaking, and what it meant. Over the past year and a half, we've evolved in our thinking by reviewing the literature on understanding and improving policymaking. We realized that there's a lot to learn from this literature, and that we could raise the standards in the EA community’s approach to policymaking.

We are a group of longtermists, so we take a longtermist perspective. The book is 50,000 words and five chapters. There’s one chapter on why political institutions, because they enable large-scale action and regulation, are important and effective instruments to foster longtermism. We also explain why they currently are short-termist, and then sketch out the questions we need to answer to go further.

Then, we have a chapter on understanding policymaking from the bottom up. There's a lot of talk about political institutions as large, macro structures. We delve into political behavior, the drivers of political attention, and what influences priority-setting in policy.

In the third chapter, we try to address how to robustly engage in policymaking. We re-reviewed the evidence from the teachings of the advocacy lobbying and epistemic communities, and derived advice for longtermist political engagement. We ask, “What kinds of strategies and tactics should we use? Should we [protest in] the streets [and engage in] political outsider tactics, or work together with policymakers?

The fourth chapter is the one that I just presented. Decision-making is key, and we need to better understand what we can do, in practical terms, to improve our decisions.

The last chapter presents an agenda for further research and practice, with research questions and recommendations. We are quite far along in writing the book. It always takes more time than planned, but we hope to have a full manuscript by the end of this summer [2020]. And since it's a short format, hopefully it will be published either by the end of the year or in early 2021.

Habiba: Amazing. People have a lot of questions covering the range of [topics] in the book. To start, Nathan Young has asked, “What are some of the top interventions that we should keep in mind when we're thinking about this topic?”

Max: [In terms of] improving political decision-making?

Habiba: Yes.

Max: I think it really depends who is asking this question. [If it’s] an academic institution that produces evidence to be used by policymakers, I think it’s relevant to design research together with policymakers, such that the evidence produced is directly placed [in context].

But if this question is asked by a policymaker, then I think it is very difficult to answer. I feel like some of the strategies that I outlined could be picked up by those actors. I think there is something in the quick multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) that could be applied by policymakers, bureaucrats, or technical officers.

However, I don't think that those strategies would necessarily apply when it comes to decisions made by politicians. [What] seems quite valuable is to increase the amount of information shared, and the amount of alignment or framing of different issues, among different politicians. One key problem that politicians face is the ambiguity of policy problems; they use different interpretations and reinforce this problem. I think the more we can minimize this [lack of alignment], the more cooperation we may get.

But as you can see, the more in-depth we go, the more uncertain it gets. It's quite difficult to say what's most effective.

Habiba: Yes. Who are the important actors in this space, and which are the most important to focus on? Someone has asked to what extent governments are important versus other bodies like lobbying groups. And someone else has asked, “How important do you think it is to educate decision makers versus the public in a democratic context?”

Max: There are many questions within that. We really can't just say government is more important than lobbying. If you look at a policymaking system, there’s an interplay between government officials and lobbyists. The result of the policymaking process is the interaction between those two, and the social and technical [elements of seeking] compromises amid their different interests. But I do not think that lobbyists are more important than governments.

However, in our book, when we reviewed the evidence on advocacy and lobbying strategies, both groups rely on insider and outsider tactics. They educate and work with bureaucrats and policymakers. But they also tend to use large campaigns to educate the general public. Given the small bits of evidence we have, at the moment it seems that insider strategies work better. I think right now if I were to allocate resources to improve policymaking, I’d focus on educating policymakers.

I don't know if “educating” is the right word, because many policymakers have PhDs in their fields. I think “decision-making support” is probably more relevant, and having an entity that brings them strategies and is really good at training policymakers to use those strategies [is a better way to frame it].

Habiba: Then, specifically on the question of educating decision makers versus the public—

Max: I would say decision makers; [I’d basically lean more toward] insider strategies than outsider strategies.

Habiba: That makes sense.

The top-voted question, which spans many different areas, is this: How do we incentivize governments to work on longer-term policies that extend beyond their normal time in office? In a follow-up question, someone specifically mentioned that a lot of policymaking is a knee-jerk reaction based on past events rather than being science-based and [future-oriented].

Max: I think to answer these questions, we need to understand where the structures of government institutions come from. There's actually a lot of path dependency. The system might be unitary and majoritory because of a long tradition, or a monarchy system. And we cannot change that in one day. But this is something that people in the EA community and beyond have been thinking about. For example, there's a [relevant] book called Institutions For Future Generations.

I think one way to improve and incentivize governments to consider future generations is to implement those mechanisms to represent future generations. We can act like an ombudsman for future generations. Those mechanisms could be different voting systems, different election systems, or a different form of a bank to allocate funding differently. I think right now we have an idea of those other mechanisms. There are more than 60 we [might reconfigure]. We just don't know which ones are the most effective. [Transcriber's note: see sample mechanisms and institutions here.] I think more analysis of those mechanisms [would help], especially since they come from political philosophy in the first place. That's one part: reforming the structures. And that will take a long time.

Also, I think we can use the current routes to influence policy. There are negotiations that are open to civil society, to NGOs, and to academics — that call for experts. What I realized by interacting with more and more policymakers is that there's a pretty strong openness to third-party information and preferences when policymakers craft policies. The relevant ones are relevant because they satisfy the preferences of the stakeholders.

If we use these existing routes — for example, with lobbying groups that have a longtermist focus — that will be relevant. What we're trying to do in Geneva more and more is to [leverage] disciplines that can support strategies with a longtermist angle. We're going to launch a serious game on biorisks at the World Economic Forum (WEF), and then at the United Nations. The goal will be to simply sensitize people to the probability and severity of different risks, and use a simulated setting to let them experience what this means. I think a lot of sensitization needs to [happen] before we can talk about actual policies.

Then, we can work with existing institutions, like the Biological Weapons Convention, to try to improve their resources and support them with more intelligence and tools.

Habiba: Yes. I think this touches on another question: Do you have a general sense of how recalcitrant decision makers are regarding changes to their processes? When you come to someone and suggest that they might use [a particular] tool, do they receive that suggestion well, or are they stuck in their ways?

Max: We interviewed a lot of policymakers, technical officers within governments, and diplomats for the book. What I heard is that improving those processes is the elephant in the room. Everybody knows about it and everybody knows that it's important. But it's very difficult to change the mental processes of how we act within political institutions where we are so time-constrained to do the work [that the job requires]. It’s not necessarily that they don't want to [try new processes]; it's that they don't have the time. They will need extra support to do it.

I had discussions within the United Nations, where we pitch different kinds of trainings, for example on serious games. What was really interesting was that they’d say, “Yeah, this is relevant, but what's the evidence behind it?" They were asking about the effectiveness of those trainings. And when I explained what MCDA is, and the evidence that exists behind it, they were very interested, because there are decades of use of that strategy. I faced pretty rigorous responses.

But I also observed other types of responses, especially from diplomats, who would say, “Oh, you basically are trying to make us better. But policymaking is so complex, and we need to accept that we cannot control the process. We just need to let go of our [processes], and network, network, network.” I found this view a bit cynical, and this is not shared in all policymaking systems. But it’s definitely good to know [that some people hold it] before trying to supply ideas.

Habiba: It's a view that seems a little bit scary from the perspective of someone within a democratic society, because it feels uncontrolled. But it just depends on how robustly it leads to good outcomes or not. It's interesting to get that insight.

A few people have asked questions around what MCDAs and serious games are. Could you give a short introduction to those?

Max: It's much easier [to describe] MCDA than serious games. MCDA stands for multiple-criteria decision analysis. An example would be a cost-benefit analysis. But this only has two criteria. The idea of MCDAs is to have many more criteria, and it's a formal process that would guide decision makers through defining their context, then the problem, then the criteria to assess solutions to the problem. Next, they’d brainstorm options, assess all the options against those criteria, and then deal with quantitative and qualitative data on those options. I think it's especially important that MCDAs allow us to quantify a judgment, because in policymaking there are a lot of judgment calls.

MCDA makes judgments explicit, and sometimes quantifies them, such that they are understood by the stakeholders and the people who participate in the decision-making.

MCDA is not just one method; it actually includes more than 60 methods. One of the key problems is that different methods lead to different results. So we need to have really good knowledge about which methods to select. There's literature on this, and a lot of debates, but this is one of the main limitations.

There’s a vast range of serious games. They include almost any game that has an educational purpose. They range from video games, to digital games, to card games. In our book, we [focused on] impersonal games that simulate scenarios. It's known to be useful because it shortens the feedback loop between making decisions and [being aware of] their effects. It's basically like a simulator, where people try different ideas, but also practice communicating about complex problems. There's a vast amount of literature on this and I highly recommend you read about it.

Habiba: Great. We're just about out of time for the Q&A. But to finish off, if people are interested in this, what should they study, and how can they get more involved — for example in the particular recommendations [you made]?

Max: I encourage them to reach out to us, because there will be many more opportunities in the future, in Geneva and beyond. I think there's a tendency when we do research to focus on original studies that produce new evidence. And I think what is often much more valuable than doing small bits of research that we might not be able to replicate is to commit to conducting synthesis research, and ideally, a meta-analysis or systematic review. I would encourage you to do this. It's also somewhat easier to do.

In terms of studies, there are programs in the decision sciences that are particularly interesting. I think I would also put the focus on understanding and supporting decision-making under high-uncertainty, connective settings. We know a bit more about how to optimize our individual decision-making in contexts where we have full information and a lot of time to think about the decisions.

In connective settings, multiple people have different interpretations, time constraints, and high uncertainty about the problems and the solutions. Those are extremely difficult problems. I think [it’s definitely advisable to focus on] policymaking that does not follow an ideal scenario in which people have full information.

Habiba: Yes. Thank you so much. I have gone slightly over time. I'm sorry, folks. That concludes the Q&A part of the session. [...] Thanks, everyone, for watching. Thank you, Max.

Max: Thank you.