Matthew_Barnett

Posts 11

Comments121

If we define "doom" as "some AI(s) take over the world suddenly without our consent, and then quickly kill everyone" then my p(doom) is in the single digits. (If we define it as human extinction more generally, regardless of the cause, then I have a higher probability, especially over very long time horizons.)

The scenario that I find most likely in the future looks like this:

- Although AI gets progressively better at virtually all capabilities, there aren't any further sudden jumps in general AI capabilities, much greater in size than the jump from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4. (Which isn't to say that AI progress will be slow.)

- As a result of (1), researchers roughly know what AI is capable of doing in the near-term future, and how it poses a risk to us during the relevant parts of the takeoff.

- Before AI becomes dangerous enough to pose a takeover risk, politicians pass legislation regulating AI deployment. This legislation is wide reaching, and allows the government to extensively monitor compute resources and software.

- AI labs spend considerable amounts of money (many billions of dollars) on AI safety to ensure they can pass government audits, and win the public's trust. (Another possibility is that foundation model development is taken over by the government.)

- People are generally very cautious about deploying AI in safety-critical situations. AI takes over important management roles only after people become very comfortable with the technology.

- AI alignment is not an intractable problem, and SGD naturally finds human-friendly agents when rewarding models for good behavior in an exhaustive set of situations that they might reasonably expect to encounter. This is especially true when combined with whatever clever tricks we come up with in the future. While deception is compatible with the behavior we reward AIs for, it is usually simpler to just "be good" than to lie.

- Even though some value misalignment slips through the cracks after auditing AIs using mechanistic interpretability tools, AI misalignment is typically slight rather than severe. This means that most AIs aren't interested in killing all humans.

- Eventually, competitive pressures force people to adopt AIs to automate just about every possible type of job, including management, giving AIs effective control of the world.

- Humans retire as their wages fall to near zero. A large welfare state is constructed to pay income to people who did not own capital prior to the AI transition period. Even though inequality becomes very high after this transition, the vast majority of people become better off in material terms than the norm in 2023.

- The world continues to evolve with AIs in control. Even though humans are retired, history has not yet ended.

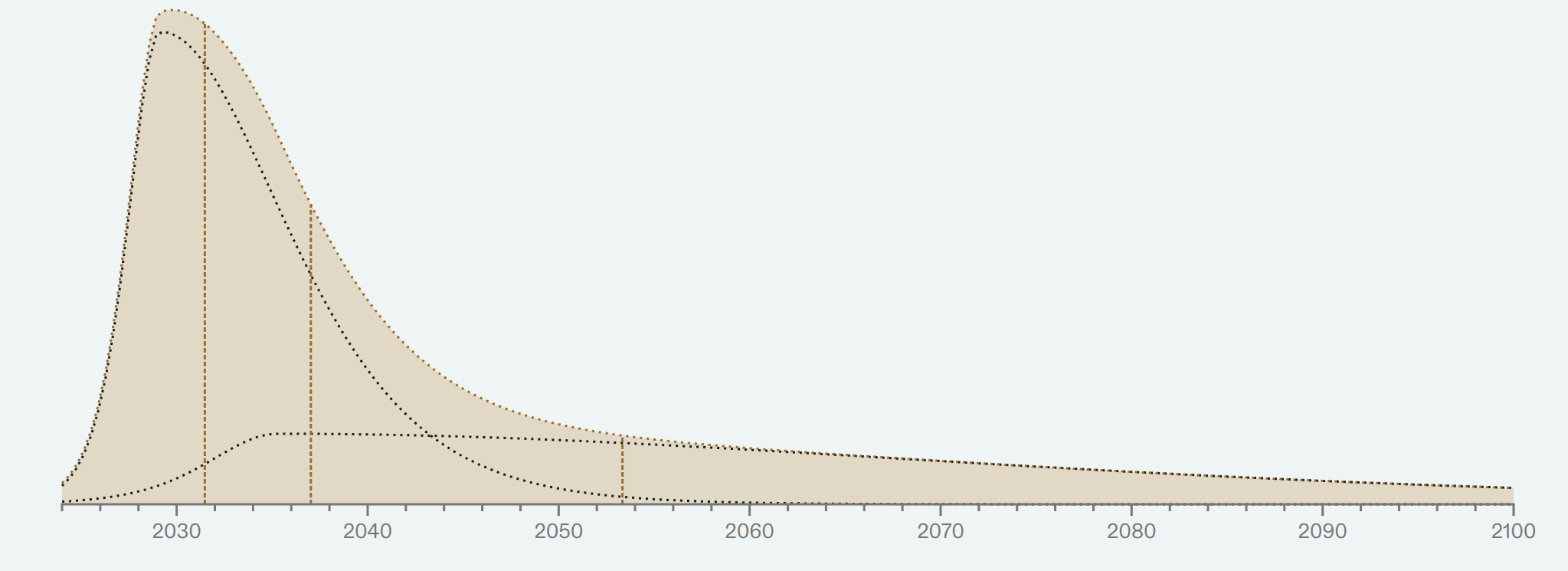

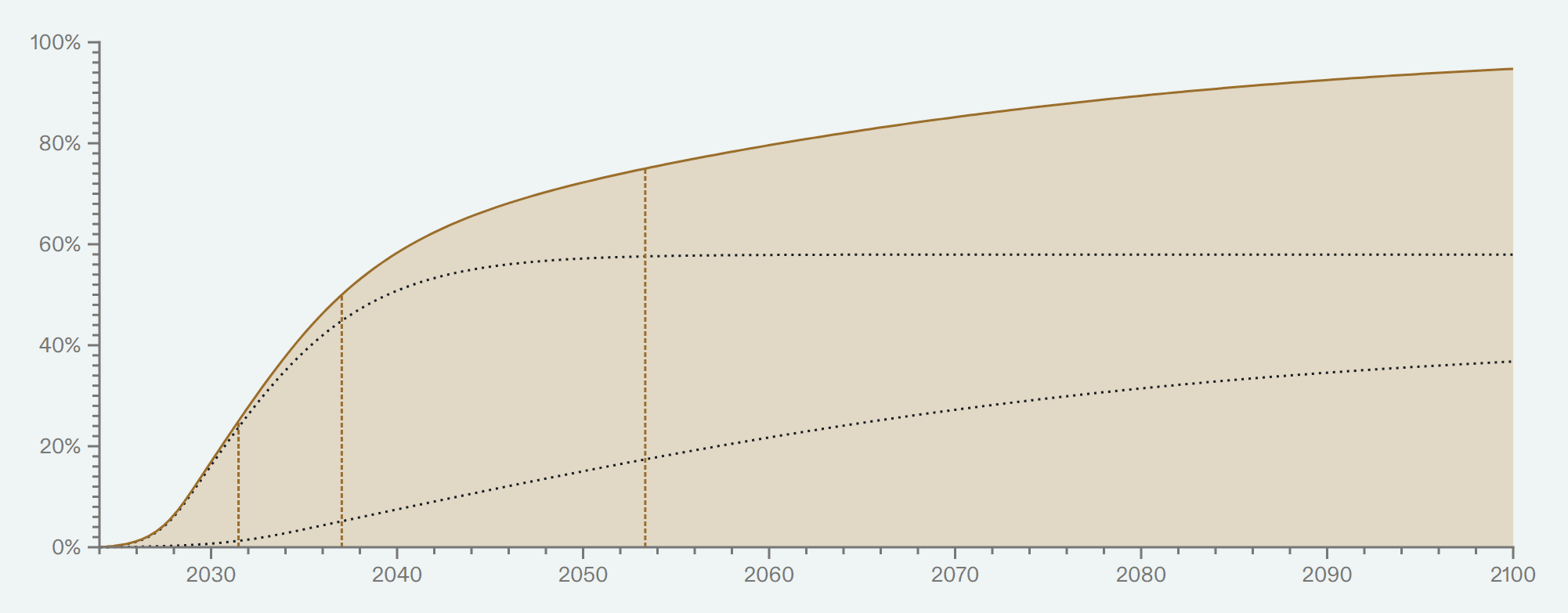

I thought it would be useful to append my personal TAI timelines conditional on no coordinated delays, no substantial regulation, no great power wars or other large exogenous catastrophes, no global economic depression, and that my basic beliefs about reality are more-or-less correct (e.g. I'm not living in a simulation or experiencing a psychotic break).

As you can see, this results in substantially different timelines. I think these results might be more useful for gauging how close I think we are to developing the technologies for radically transforming our world. I've added these plots in a footnote.

I'm also a little surprised you think that modeling when we will have systems using similar compute as the human brain is very helpful for modeling when economic growth rates will change.

In this post, when I mentioned human brain FLOP, it was mainly used as a quick estimate of AGI inference costs. However, different methodologies produce similar results (generally within 2 OOMs). A standard formula to estimate compute costs is 6*N per forward pass, where N is the number of parameters. Currently the largest language models have are estimated to be between 100 billion to 1 trillion parameters, which would work out to being 6e11 to 6e12 FLOP/forward pass.

The chinchilla scaling law suggests that inference costs will grow at about half the rate of training compute costs. If we take the estimate of 10^32 training FLOP for TAI (in 2023 algorithms) that I gave in the post, which was itself partly based on the Direct Approach, then we'd expect inference costs to grow to something like 1e15-1e16 per forward pass, although I expect subsequent algorithmic progress will bring this figure down, depending on how much algorithmic progress translates into data efficiency vs. parameter efficiency. A remaining uncertainty here is how a single forward pass for a TAI model will compare to one second of inference for humans, although I'm inclined to think that they'll be fairly similar.

I think this is a poor way to describe a reasonable underlying point. Heavier-than-air flying machines were pursued for centuries, but airplanes appeared almost instantly (on a historic scale) after the development of engines with sufficient power density. Nonetheless, it would be confusing to say "flying is more about engine power than the right theories of flight". Both are required.

I agree. A better phrasing could have emphasized that, although both theory and compute are required, in practice, the compute part seems to be the crucial bottleneck. The 'theories' that drive deep learning are famously pretty shallow, and most progress seems to come from tinkering, scaling, and writing code to be more efficient. I'm not aware of any major algorithmic contribution that would not have been possible if it were not for some fundamental analysis from deep learning theory (though perhaps these happen all the time and I'm just not sufficiently familiar to know).

As you observe, algorithmic progress has been comparable to compute progress (both within and outside of AI). You list three "main explanations" for where algorithmic progress ultimately comes from and observe that only two of them explain the similar rates of progress in algorithms and compute. But both of these draw a causal path from compute to algorithms without considering the (to-me-very-natural) explanation that some third thing is driving them both at a similar rate. There are a lot of options for this third thing! Researcher-to-researcher communication timescales, the growth rate of the economy, the individual learning rate of humans, new tech adoption speed, etc.

I think the alternative theory of a common cause is somewhat plausible, but I don't see any particular reason to believe in it. If there were a common factor that caused progress in computer hardware and algorithms to proceed at a similar rate, why wouldn't other technologies that shared that cause grow at similar rates?

Hardware progress has been incredibly fast over the last 70 years -- indeed, many people say that the speed of computers is by far the most salient difference between the world in 1973 and 2023. And yet algorithmic progress has apparently been similarly rapid, which seems hard to square with a theory of a general factor that causes innovation to proceed at similar rates. Surely there are such bottlenecks that slow down progress in both places, but the question is what explains the coincidence in rates.

Humans have been automating mechanical task for many centuries, and information-processing tasks for many decades. Moore's law, the growth rate of the thing (compute) that you ague drives everything else, has been stated explicitly for almost 58 years (and presumably applicable for at least a few decade before that). Why are you drawing a distinction between all the information processing that happened in the past and "AI", which you seem to be taking as a basket of things that have mostly not had a chance to be applied yet (so no data)?

I expect innovation in AI in the future will take a different form than innovation in the past.

When innovating in the past, people generally found a narrow tool or method that improved efficiency in one narrow domain, without being able to substitute for human labor across a wide variety of domains. Occasionally, people stumbled upon general purpose technologies that were unusually useful across a variety of situations, although by-and-large these technologies are quite narrow compared to human resourcefulness. By contrast, I think it's far more plausible that ML foundation models allow us to create models that can substitute for human labor across nearly all domains at once, once a sufficient scale is reached. This would happen because sufficiently capable foundation models can be cheaply fine-tuned to provide a competent worker for nearly any task.

This is essentially the theory that there's something like "general intelligence" which causes human labor to be so useful across a very large variety of situations compared to physical capital. This is also related to transfer learning and task-specific bottlenecks that I talked about in Part 2. Given that human population growth seems to have caused a "productivity explosion" in the past (relative to pre-agricultural rates of growth), it seems highly probable that AI could do something similar in the future if it can substitute for human labor.

That said, I'm sympathetic to the model that says future AI innovation will happen without much transfer to other domains, more similar to innovation in the past. This is one reason (among many) that my final probability distribution in the post has a long tail extending many decades into the future.

Thanks for the comment.

You predict when transformative AGI will arrive by building a model that predicts when we'll have enough compute to train an AGI.

But I feel like there's a giant missing link - what are the odds that training an AGI causes 1, 2, or 3?

I think you're right that my post neglected to discuss these considerations. On the other hand, my bottom-line probability distribution at the end of the post deliberately has a long tail to take into account delays such as high cost, regulation, fine-tuning, safety evaluation, and so on. For these reasons, I don't think I'm being too aggressive.

Regarding the point about high cost in particular: it seems unlikely to me that TAI will have a prohibitively high inference cost. As you know, Joseph Carlsmith estimated brain FLOP with a central estimate of 10^15 FLOP/s. This is orders of magnitude higher than the cost of LLMs today, and it would still be comparable to prevailing human wages at current hardware prices. In addition, there are more considerations that push me towards TAI being cheap:

- A large fraction of our economy can be automated without physical robots. The relevant brain anchor for intellectual tasks is arguably the cerebral cortex rather than the full human brain. And according to Wikipedia, "There are between 14 and 16 billion neurons in the human cerebral cortex." It's not clear to me how many synapses there are in the cerebral cortex, but if the synapse-to-neuron ratio is consistent throughout the brain, then the inference cost of the cerebral cortex is plausibly about 1/5th the inference cost of the whole brain.

- The human brain is plausibly undertrained relative to its size, due to evolutionary constraints that push hard against delaying maturity in animals. As a consequence, ML models with brain-level efficiency can probably match human performance at much lower size (and thus, inference cost). I currently expect this consideration to mean that the human brain is 2-10x larger than "necessary".

- The chinchilla scaling laws suggest that inference costs should grow at about half the rate as training costs. This is essentially the dual consideration of the argument I gave in the post about data not being a major bottleneck.

- We seem to have a wider range of strategies available for cutting down the cost of inference compared to evolution. I'm not sure about this consideration though.

I'm aware that you have some counterarguments to these points in your own paper, but I haven't finished reading it yet.

A 10^29 FLOP training run is an x-risk itself in terms of takeover risk from inner misalignment during training, fine-tuning or evals (lab leak risk).

I'm not convinced that AI lab leaks are significant sources of x-risks, but I can understand your frustration with my predictions if you disagree with that. In the post, I mentioned that I disagree with hard takeoff models of AI, which might explain our disagreement.

Regulation - hopefully this will slow things down, but for the sake of argument (i.e. in order to argue for regulation) it's best to not incorporate it into this analysis.

I'm not sure about that. It seems like you might still want to factor in the effects of regulation into your analysis even if you're arguing for regulation. But even so, I'm not trying to make an argument for regulation in this post. I'm just trying to predict the future.

General-purpose robotics - what do you make of Google's recent progress (e.g. robots learning all the classic soccer tactics and skills from scratch)?

I think this result is very interesting, but my impression is that the result is generally in line with the slow progress we've seen over the last 10 years. I'll be more impressed when I start seeing results that work well in a diverse array of settings, across multiple different types of tasks, with no guarantees about the environment, at speeds comparable to human workers, and with high reliability. I currently don't expect results like that until the end of the 2020s.

Epoch says on your trends page: "4.2x/year growth rate in the training compute of milestone systems". Do you expect this trend to break in less than 4 years?

I wouldn't be very surprised if the 4.2x/year trend continued for another 4 years, although I expect it to slow down some time before 2030, especially for the largest training run. If it became obvious that the trend was not slowing down, I would very likely update towards shorter timelines. Indeed, I believe the trend from 2010-2015 was a bit faster than from 2015-2022, and from 2017-2023 the largest training run (according to Epoch data) went from ~3*10^23 FLOP to ~2*10^25 FLOP, which was only an increase of about 0.33 OOMs per year.

1 OOM per year (as per Epoch trends, inc. algorithmic improvement) is 10^29 in 2027.

But I was talking about physical FLOP in the comment above. My median for the amount of FLOP required to train TAI is closer to 10^32 FLOP using 2023 algorithms, which was defined in the post in a specific way. Given this median, I agree there is a small (perhaps 15% chance) that TAI can be trained at 10^29 2023 FLOP, which means I think there's a non-negligible chance that TAI could be trained in 2027. However, I expect the actual explosive growth part to happen at least a year later, though, for reasons I outlined above.

I can only speak for myself here, not Epoch, but I don't believe in using the security mindset when making predictions. I also dispute the suggestion that I'm trying to be conservative in a classic academic prestige-seeking sense. My predictions are simply based on what I think is actually true, to the best of my abilities.

Thanks. My section on very short timelines focused mainly on deployment, rather than training. I actually think it's at least somewhat likely that ~AGI will be trained in the next 4 years, but I expect a lot of intermediate steps between the start of that training run and when we see >30% world GDP growth within one year.

My guess is that the pre-training stage of such a training run will take place over 3-9 months, with 6-12 months of fine-tuning, and safety evaluation. Then, deployment itself likely adds another 1-3 years to the timeline even without regulation, as new hardware would need to be built or repurposed to support the massive amounts of inference required for explosive growth, and people need time to adjust their workflows to incorporate AIs. Even if an AGI training run started right now, I would still bet against it increasing world GDP growth to >30% in 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026. The additional considerations of regulation and the lack of general-purpose robotics pushes my credence in very short timelines to very low levels, although my probability distribution begins to sharply increase after 2026 until hitting a peak in ~2032.

If we take the total of 10^22 FLOP/s estimated to be available, and use that for training over ~4 months (10^7 seconds), we get a training run of of 10^29 FLOP.

I think the 10^22 FLOP/s figure is really conservative. It made some strong assumptions like:

- We can gather up all the AI hardware that's ever been sold and use it to run models.

- The H100 can run at 4000 TFLOP/s. My guess is that the true number is less than half.

My guess is that a single actor (even the US Government) could collect at most 30% of existing hardware at the moment, and I would guess that anyone who did this would not immediately spend all of their hardware on a single training run. They would probably first try a more gradual scale-up to avoid wasting a lot of money on a botched ultra-expensive training run. Moreover, almost all commercial actors are going to want to allocate a large fraction -- probably the majority -- of their compute to inference simultaneously with training.

My central estimate of the amount of FLOP that any single actor can get their hands on right now is closer to 10^20 FLOP/s, and maybe 10^21 FLOP/s for the US government if for some reason we suddenly treated that as a global priority.

If I had to guess, I'd predict that the US government could do a 10^27 FLOP training run by the end of next year, with some chance of a 10^28 training run within the next 4 years. A 10^29 FLOP training run within 4 years doesn't seem plausible to me even with US government-levels of spending, simply because we need to greatly expand GPU production before that becomes a realistic option.

In fact, if we factor in algorithmic progress going in lockstep with compute increases (which as you say is plausible[5]), then we get another 3 OOMs for free

I don't think that's realistic in a very short period of time. In the post, I suggested that algorithmic progress either comes from from insights that are enabled by scale, or algorithmic experimentation. If progress were caused by algorithmic experimentation, then there's no mechanism by which it would scale with training runs independent of a simultaneous scale-up of experiments.

It also seems unlikely that we'd get 3 OOMs for free if progress is caused by insights that are enabled by scale. I suspect that if the US government were to dump 10^28 FLOP on a single training run in the next 4 years, they would use a tried-and-tested algorithm rather than trying something completely different to see if it works on a much greater scale than anything before. Like I said above, it seems more likely to me that actors will gradually scale up their compute budgets over the next few years to avoid wasting a lot of money on a single botched training run (though by "gradual" I mean something closer to 1 OOM per year than 0.2 OOMs per year).

I don't expect human brain emulations to be competitive with pure software AI. The main reason is that by the time we have the ability to simulate the human brain, I expect our AIs will already be better than humans at almost any cognitive task. We still haven't simulated the simplest of organisms, and there are some good a priori reasons to think that software is easier to improve than brain emulation technology.

I definitely think we could try to merge with AIs to try to keep up with the pace of the world in general, but I don't think this approach would allow us to surpass ordinary software progress.