Deep Uncertainty

We talk about deep uncertainties when parties to a decision do not know, or cannot agree on[1]

- the system model that relates action to consequences,

- the probability distributions to place over the inputs to these models, or

- which consequences to consider and their relative importance.

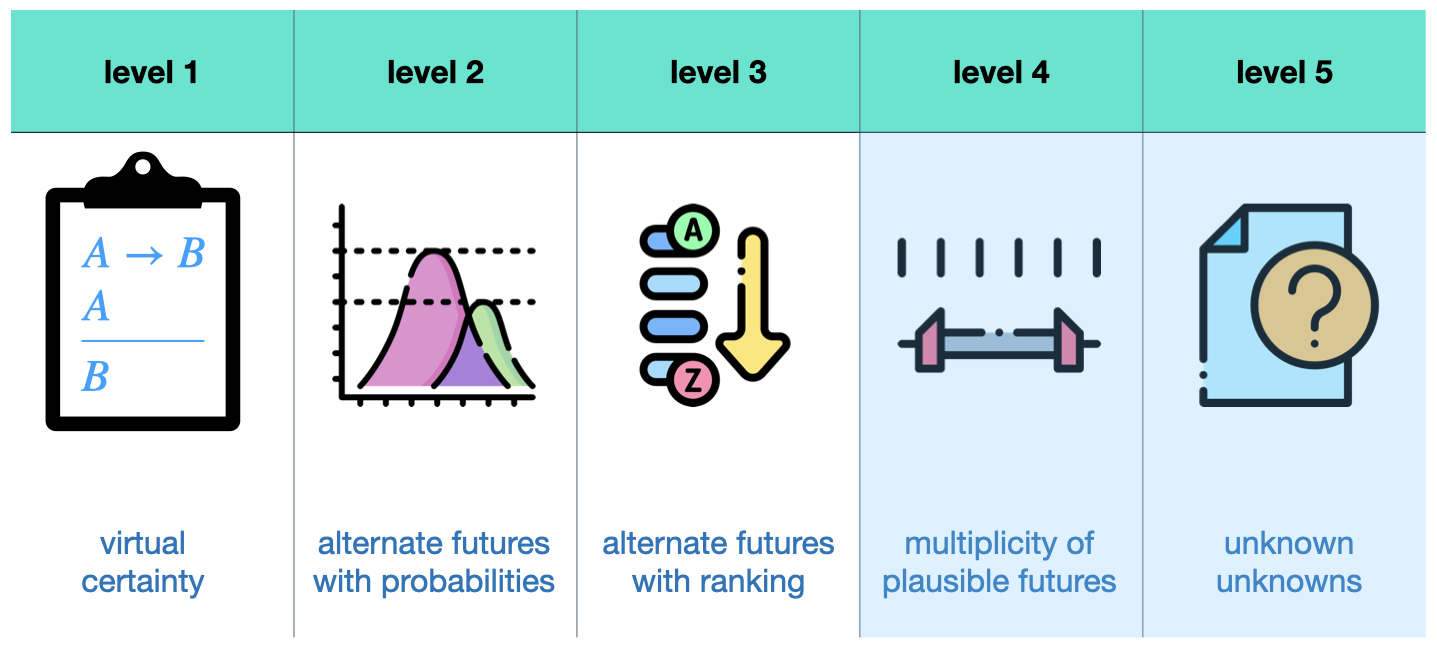

The first point (system model mapping) relates often to structural uncertainty in which we do not know how a natural system maps input and outputs. We are not certain about (some of) the underlying structures or functions within the formal model. The third point (consequence and relative importance) refers to the standard approach of oversimplification and aggregation and putting some a priori weights on several objectives. We will elaborate on this point further down the text. The second point (probability distributions) relates to that we do not know how likely particular values for particular input variables are. This is especially the case when we are looking at very rare events for which a frequentist probability is usually tricky. To elaborate on this, consider the table below. In this context, the literature distinguishes 5 levels of uncertainty[2].

On the first level, you are looking at virtual certainty. It's (basically) a deterministic system. Level 2 uncertainty is the kind of uncertainty that most people refer to when they say uncertainty. It's the assumption that you know the probability distribution over alternate futures and is on a ratio scale[3]. Level 3 uncertainty is already rarer in its usage. It refers to alternate futures that you can only rank by their probabilities and is on an ordinal scale. In this case, we do not know the exact probabilities of future events but only which ones are more likely than others without indicating how much more likely.

Deep uncertainties refer to levels 4 and 5 uncertainties. Level 4 uncertainties refer to a situation in which you know about what outcomes are possible but you do not know anything about their probability distributions, not even the ranking. It's just a set of plausible futures. This is an extraordinarily important consideration! If true, this breaks expected-utility thinking.

Expected-Utility Thinking is in Trouble

In the absence of probability distributions, expected-utility thinking becomes useless, as it relies on accurate assessments of probabilities to determine the expected value of different options. How do you calculate expected utility if you do not know what to expect? Spoiler alert: You don't! Some would make the argument that we often do not know the probability distributions over many external factors that affect our systems. Sure, we know how likely a dice role is to yield a 5. But do we really know how likely it is that AGI will be devised, tested, and publicly announced by 2039? As Bayesians, we might tend to think that we can. But how useful are such kinds of probability distributions? A more modest position would consist in acknowledging that we do know these probability distributions. We might argue that we know plausible date ranges. But this doesn't sit well with expected-utility thinking.

...